Since the great Kennedy-Nixon US Presidential debate of 1960, the spectre of a televised debate – for that is how it must have appeared to many a Party leader – has loomed large over nearly every UK general election. For 50 years, however, British politicians have clung doggedly to the staid approach of the Party Political Broadcast – until this month, of course.

Harold Wilson was the first British politician to propose a televised debate in the UK. He challenged

Sir Alec Douglas-Home to a debate during the 1964 election, but Home refused, comparing the prospect to a Top of the Pops competition:

You’ll then get the best actor as leader of the country and the actor will be prompted by a scriptwriter (Sir Alec Douglas-Home, in interview with Michael Cockerell, 2010).

However, once Wilson was himself PM, he turned down

Edward Heath’s challenge to a 1970 debate – a pattern which was to endure until

John Major offered one to

Tony Blair in 1997.

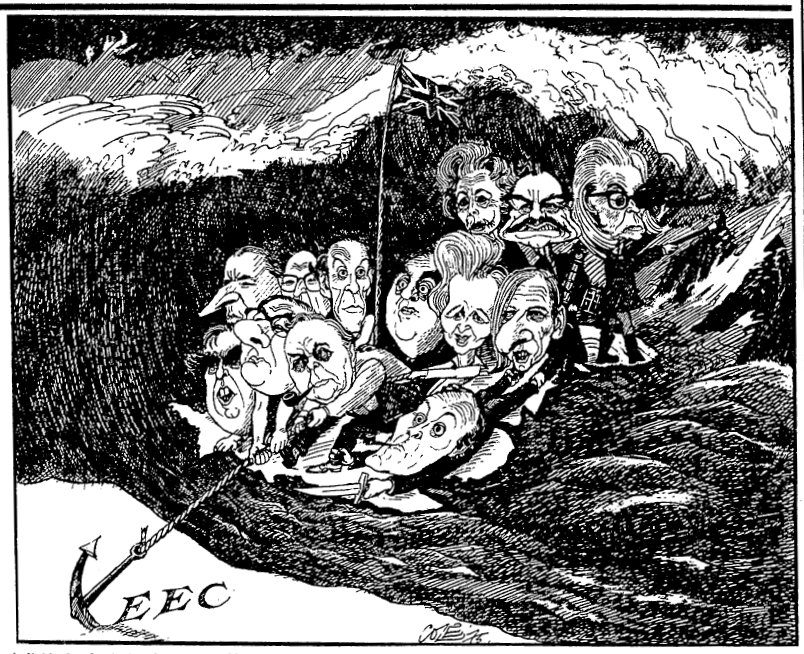

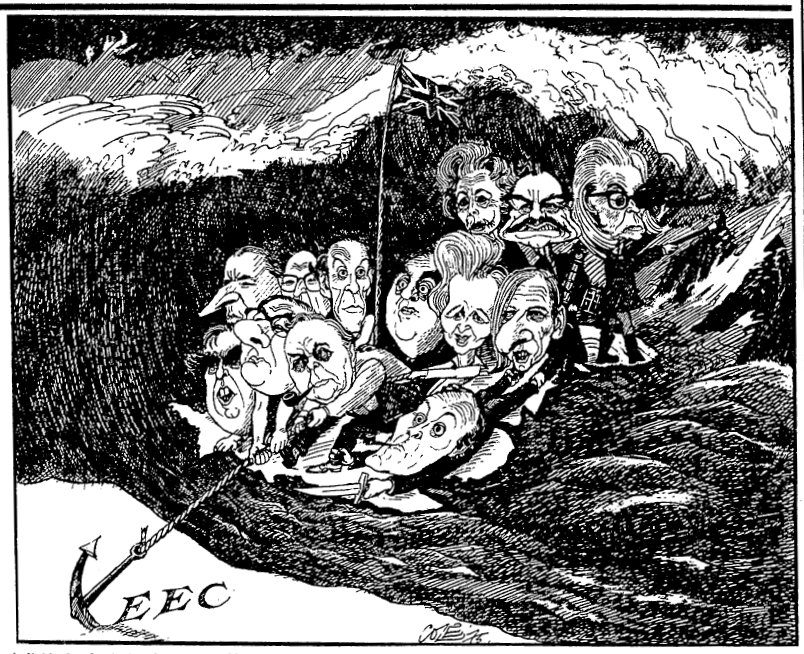

Despite the PMs’ reluctance, the first ever televised debate took place 25 years ago –at the height of the referendum debate over Britain’s continued membership of the EEC. Leading politicians from the three major parties locked horns in three televised debates, and many of them secured their reputations as great orators. On 2 June 1975,

Tony Benn and

Roy Jenkins, both members of the Labour Cabinet, took opposing sides in a one-on-one debate for BBC1’s

Panorama. That same evening, ITV presented a parliamentary-style debate on the motion ‘That Britain should remain in the European Economic Community’. The motion was proposed by Edward Heath, supported by Roy Jenkins, and opposed by

Enoch Powell, supported by Tony Benn (although the latter was subsequently replaced on account of his refusal to share a cross-Party platform).

The following night, BBC1 broadcast an Oxford Union debate on the motion, ‘That this House would say “Yes” to Europe’, with Edward Heath and

Jeremy Thorpe lined up against

Barbara Castle and

Peter Shore.

Jeremy Thorpe had been the only party leader to take part in these debates, but other leaders and electoral hopefuls began to consider the possibility of similar public encounters.

James Callaghan’s challenge was met with a lukewarm response from Margaret Thatcher but not outright rejection. When the proposal was first mooted through the BBC’s Director-General

Ian Trethowan in July 1978, the Conservatives’ Strategy and Tactics Committee merely agreed that

At this stage we should make no commitment on the principle but ask the BBC to ascertain the views of the other Parties and to bring forward full proposals for discussion. (Minutes of Central Office discussion, Margaret Thatcher Foundation)

Despite her initial openness, Mrs Thatcher’s reply illuminates the parties’ strong concerns:

…What are the reactions of the other four political parties at Westminster, the Liberals, the Scottish and Welsh Nationalists, and the Ulster Unionists? … bearing in mind this is not a Presidential but a Party contest, we must know their views … what would you have in mind on format, Chairman, choice of interviewers, rules governing interviews … arrangements to ensure equality, impartiality, etc? (Letter from Thatcher to Trethowan , Margaret Thatcher Foundation)

In 2010, these same concerns would be the subject of six months’ deliberations between the parties and a detailed 76-point agreement.

A few weeks later, Trethowan was still pushing his proposal at a secret Central Office meeting. However, the BBC was insistent on it being a two-Party debate only, allowing the smaller parties other unspecified opportunities to put their case, and by the end of the meeting Trethowan had conceded that ‘If a televised debate would be bad for British politics he would rather drop the idea.’

(Minutes of Central Office discussion, Margaret Thatcher Foundation) Mrs Thatcher’s final say on the matter was even more emphatic:

I believe that issues and policies decide elections, not personalities. We should stick to that approach. We are not electing a President, we are choosing a government.(Letter from Thatcher to David Cox, Margaret Thatcher Foundation)

Yet public reaction to the first of the leaders’ debates seems to vindicate the decision to proceed, albeit a few years later; a letter to The Times dated 6 June 1976 could easily have been written in the run-up to the 2010 genera election:

Let us have more good debate of this sort on television (and on public platforms too, instead of mere unanswered speeches), so that if people are indeed inclined to the dangerous habit of denigrating politicians as a breed, they may be allowed to see them at their best …But more staged parliamentary debates and more serious face-to-face discussion – that is the way to restore respect for our precious political process and its indispensable practitioners. (Mr John Campbell, Times Digital Archive)

Related