In 1909, Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’ caused three years of turmoil in the political nation. It eventually led to the assertion – one hundred years ago – of the law-making supremacy of the House of Commons over the House of Lords.

When he presented his controversial budget in 1909, Liberal Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George wrote:

‘This is a war Budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness. I cannot help hoping and believing that before this generation has passed away, we shall have advanced a great step towards that good time, when poverty, and the wretchedness and human degradation which always follows in its camp, will be as remote to the people of this country as the wolves which once infested its forests.’

(from The National Archives).

The budget was extraordinarily divisive. Lloyd George aimed to augment the country’s provision of social services, and those in favour saw it as a way to redistribute taxation and living costs more equally. Those who would be taxed more heavily, however, were wary of the Budget and especially of the land tax it included; many ‘Conservative peers and many of the party’s MPs saw the budget as heavily redistributive (especially its land clauses and supertax) and thus as a direct attack on the wealthy.’ (Conservative Century, p. 27).

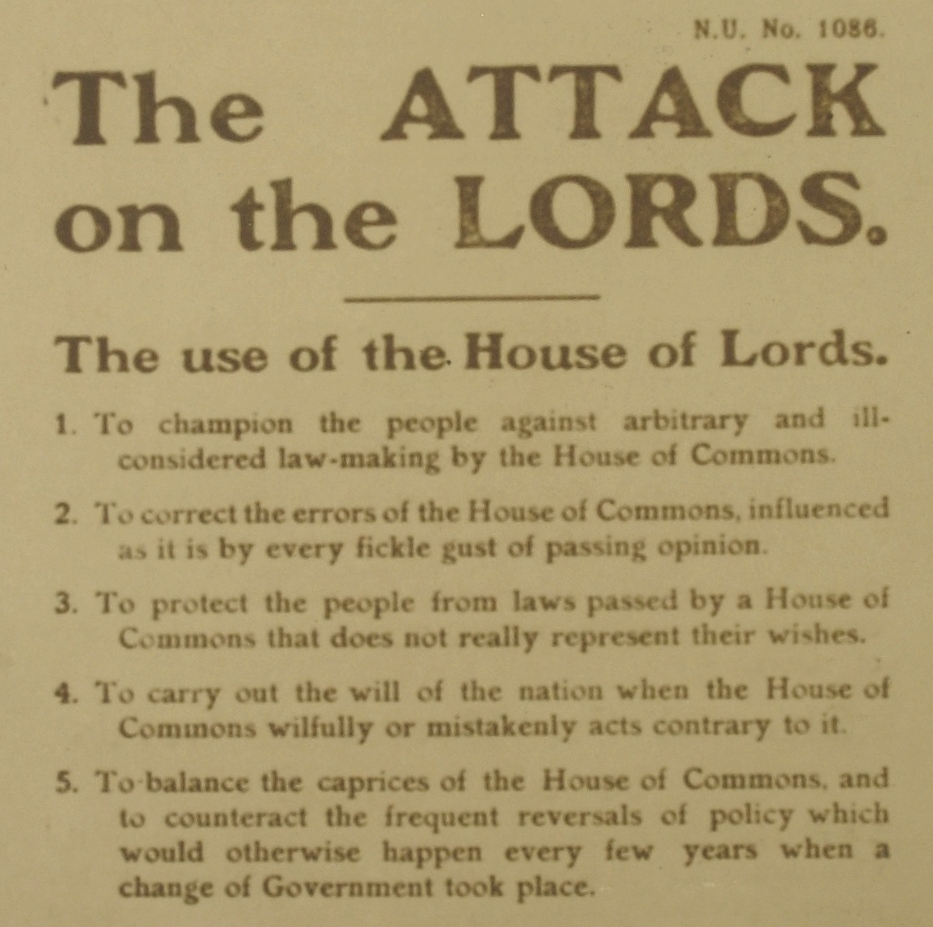

When the House of Lords – of which many members would be directly affected by the proposals – vetoed Lloyd George’s budget in 1909, the Liberals cried for reform, and a constitutional crisis was born that would take its toll on politicians from both parties. Liberal Prime Minister Asquith turned to King Edward VII for help, but the King was hesitant to give it without a mandate from the people. An early election was called in January 1910, resulting in a hung parliament – the Conservatives, led by Arthur Balfour, and their Liberal Unionist allies won the popular vote, while the Liberals, led by Asquith, returned more MPs. A coalition between the reigning Liberals and the Irish Nationalists allowed the Budget to push through; the Lords grudgingly accepted the Budget following the removal of the land tax stipulation.

The conflict was not over, however, and another battle loomed over the issue of House of Lords reform. King George V had ascended to the throne in May 1910, and he was – after some hesitation – willing to pack the House of Lords with Liberal peers if necessary to ensure the vote would swing their way. When the Lords (quite expectedly) voted against a Liberal effort to reduce their powers, a second election was called for December 1910.

The Liberal Coalition (supported by the Irish Nationalists) maintained power, and they continued to push for reform; Lloyd George wrote in the Yorkshire Observer of November 12, 1910:

‘Having in vain used every endeavour through conciliatory methods to win equal rights for all Britons, we are now driven to fight for fair play in our native land. We repudiate the claim put forward by 600 Tory Peers that they were born to control the destinies of 45,000,000 of their fellow-citizens, and to trample upon their wishes for the good government of their country.’

(noted in NUA 2/1/31 [1911 conference minutes], p. 9-10).

The Parliament Act narrowly passed a vote in the House of Lords in August 1911. It essentially removed the House of Lords’ power to veto acts sent from the House of Commons, allowing them only to delay bills (with some exceptions regarding time and bills that try to extend the length of Parliament’s term). A 1949 Act amended that of 1911 by limiting the power of the Lords to delay one year rather than two.

The Conservatives were still smarting from the defeat at their autumn 1911 conference, where they spoke of the election campaign as ‘a prodigality of misrepresentation’, citing the glaring absence of Home Rule mentions in the opposition’s rhetoric:

‘Nothing can illustrate the Election policy of the Government better than the fact that the real motive for the Election – the plot to smuggle Home Rule through Parliament – was not even mentioned in the Election Addresses of the large majority of the Minsters.’

(NUA 2/1/31, p. 10).

House of Lords reform remains a prominent and divisive issue today. The 1911 Parliament Act had stated:

‘whereas it is intended to substitute for the House of Lords as it at present exists a Second Chamber constituted on a popular instead of hereditary basis, but such substitution cannot be immediately brought into operation…’

Although as of 2011 that substitution had still not been enacted, work has begun in earnest over the past decade to define what the second chamber should look like. Since the Life Peerages Act of 1958, the shape of the Lords had begun to change, and in 1999, the House of Lords Act abolished hereditary peers (with a few exceptions), reducing the size of the House of Lords by nearly half. A Royal Commission was appointed to examine the issue in that same year, and various public consultations conducted and white papers released since then. The Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition established with the 2010 election made an elected chamber a priority (see the Coalition’s Programme for Government), and a House of Lords Reform Bill was proposed in 2010 and is working its way through committee. The draft bill can be viewed online.