In last month’s blog, we discussed Maria Edgeworth’s response to Peterloo and her concern for political reform (rather than revolution) in Ireland and in the West Indies. This month we take a look at the Edgeworth family’s global – particularly European – outlook, which went beyond politics.

A letter dated 15 September 1819 (MS. Eng. Lett. c. 704 fol. 6-7), to Henrica “Harriette” Edgeworth (née Broadhurst), wife of Maria’s brother Charles Sneyd Edgeworth, highlights in particular the cross-channel friendships and acquaintances enjoyed by the Edgeworth family. The letter was written and signed by Fanny Edgeworth, but with contributions from Maria.

It begins by responding to Harriette’s recent letter detailing her visit with her husband to Paris, which the family had clearly received with delight. Frances tells her that ‘Your visit to Madme Recamier amused us much’, but lightly berates her for the lack of details about ‘Extravagant’ Parisian life:

I wish you would enter into some particulars for my sake – tell me whether you drive your own carriage – I thought that was impossible in the streets of Paris – Tell me how much a good Voiture de service [hired carriage] costs per month –

Maria had visited Paris in 1802 with her father and would have been eager to see whether costs and customs had changed: the following year, she and Fanny would travel to France again for two months from April 1820. The letter also sees the Edgeworth sisters introducing visitors to different national customs and identities at their home in Ireland. Fanny describes a visit from some English friends, Mrs and Miss Carr.

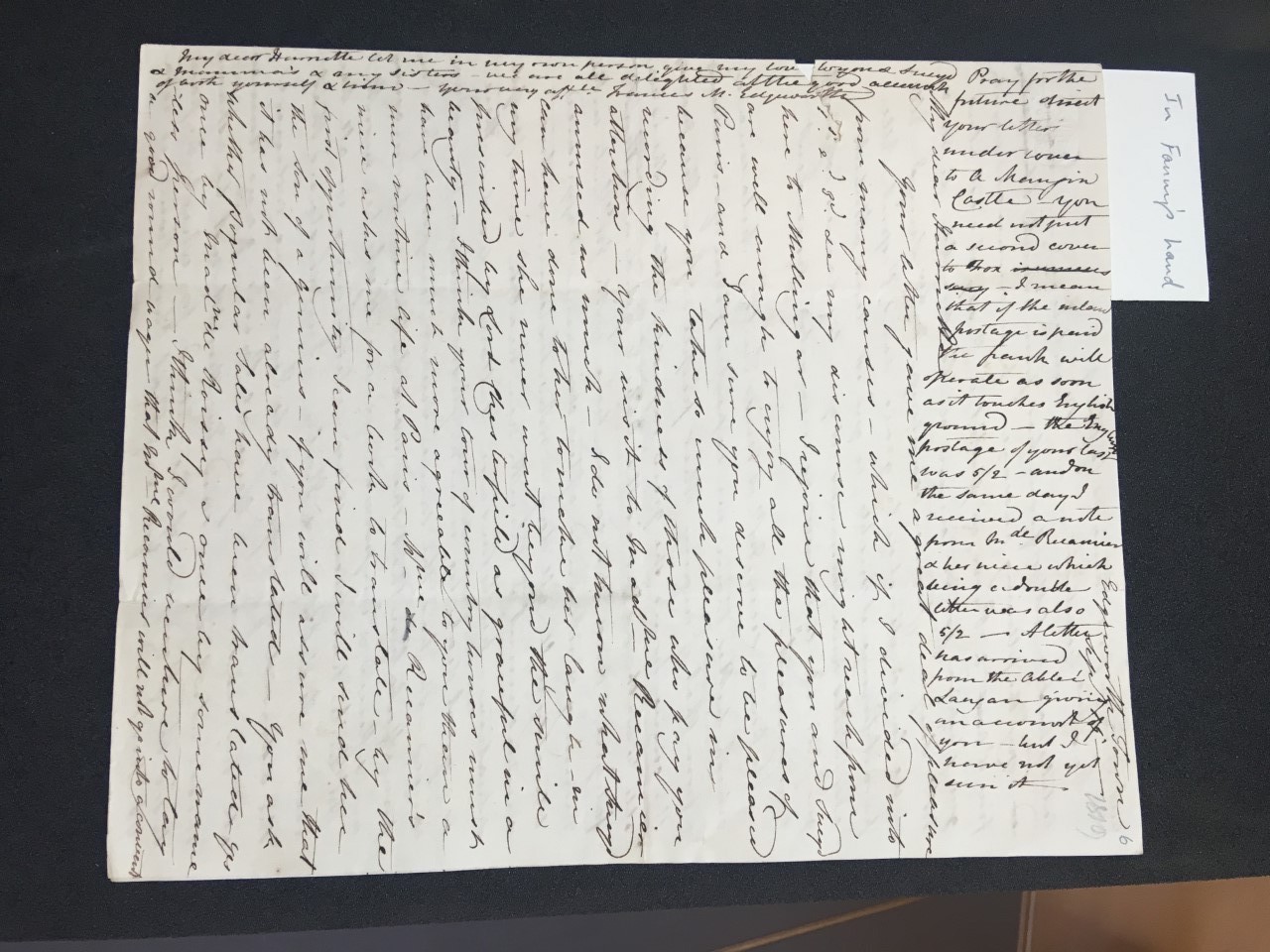

The letter treads familiar ground too; they report (once again) on the state of their sister Lucy’s bad back as well as other domestic concerns such as the cost of postage. The closing lines of the letter are written down the side of the front page – a common feature of letters written during a period in which postage cost by the page and paper was not a cheap commodity.

First page of MS. Eng. lett. c. 704 fol.6-7

First page of MS. Eng. lett. c. 704 fol.6-7

Transcription of MS. Eng. Lett. c. 704 fol.6-7

Back on the continent, another French acquaintance, Madame Gautier, had written to describe meeting Harriette and Charles during their visit, which Frances shares in the letter:

Je retournerai vers la fin d’Aout â Paris – ou plutôt â Passy et c’est alors que j’espère jouir encore de la societé de’ M – & Mde Sneyd – J’aime beaucoup Mde Sneyd –Elle a de la gaièté et de la grace dans l’esprit – Elle parait bonne et sensible – ce qui est deux attributs essentials aux femmes – il que les dames Edgeworth qui j’ai eû le plaisir de connaitre possedent <uniquement> (1)

In this passage, Madame Gautier writes about meeting Harriette and Charles in Paris. It was not only Harriette’s journey that occupied the Edgeworth circle, however. Frances tells her that ‘Mrs Tuite has been very entertaining in all her accounts of Paris & Italy’. Despite the comparative difficulties in travel in comparison with today, this letter evinces the international outlook of Maria and her circle.

Portrait of Juliette Récamier (1777-1849) by François Pascal Simon Gérard (Musée du Louvre) Source: Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Juliette Récamier (1777-1849) by François Pascal Simon Gérard (Musée du Louvre) Source: Wikimedia Commons

Maria Edgeworth was no stranger to Paris. Indeed she was herself an acquaintance of French socialite Juliette Récamier (1777-1849) (mentioned in this letter), who led a celebrated salon in Paris frequented by leading literary and political figures. The pair met during Maria’s first visit to Paris in 1802, during which Récamier took them to theatre, and where Maria’s love interest Abraham Niclas Edelcrantz (1754–1821), whom she would subsequently refuse an offer of marriage, was sitting next to Napoleon Bonaparte.

Maria corresponded with other European writers and thinkers: from 1805, for example, she corresponded with and befriended Etienne Dumont (1759–1829), later the translator of the works of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham (c. 1747/8–1832) into French – though unfortunately only a copy of a single letter Dumont wrote to Maria in 1820 exists in the Bodleian’s Edgeworth Papers (MS. Eng. lett. c. 720, fols. 56-7).

The Edgeworths’ November 1802 visit to France (the party consisted of Maria, her father and step-mother Frances, and her oldest half-sister Charlotte) came just before outbreak of war, which restricted travel between the two counties, as fellow novelist Frances Burney (1752–1840) famously discovered during her effective exile in France between 1802 and 1814.

Despite the physical constraints of journeying to France during this period, Maria was part of a cross-channel literary community. The increasingly global literary marketplace had several implications for Maria’s literary works. As Frances tells Harriette in this letter, for instance, Popular Tales (which featured ‘The Grateful Negro’, as discussed in August’s blog) had been translated into French: ‘once by Madme de Roissy & once by some name-less person’. Another of Maria Edgeworth’s French translators included her friend and sometimes collaborator, Louise Swanton Belloc, a Frenchwoman of Irish descent.

Maria’s writings were translated not only into French, but also into other European languages too: Dutch, German, Irish, Italian, Swedish, and Spanish versions of her works were published in her lifetime. A Bengali edition of her tale, Murad the Unlucky, entitled Hatbagyo Murad, was published in India in 1861, translated by Judu Gopaul Chatterjea (a copy of which exists in the British Library).

The (multiple) translations of Popular Tales speak to her status as an international literary figure. But it was actually a translation of Stéphanie-Félicité de Genlis’s (1746–1830) Adèle et Théodore that was Maria’s earliest effort prepared for publication.(2) Though it remained unpublished due to a rival translation being published first, it remains a testament to Maria’s early engagement – encouraged by her father Richard Lovell Edgeworth – with a wider European literary scene. Maria was not alone: Gillian Dow’s edited collection, Translators, Interpreters, Mediators: Women Writers 1700-1900, showcases the rich traffic between English and other European texts and the role women played in circulating, translating and producing these works in their own languages.

Translation was also a vital means of disseminating the progressive educational ideals the Edgeworth family sought to promote, ideals always in dialogue with that of French thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) and de Genlis. Maria recommends a text for the niece of Juliette Récamier to translate which also promises to educate the young woman in the thinking of an English ‘genius’ who was an important member of Robert Lovell Edgeworth’s circle of scientific speculators. Humphry Davy (1778-1829), Cornish chemist and inventor, wrote his poem ‘The Sons of Genius’, when he was just 17. Published in Robert Southey’s The Annual Anthology in 1799, it honours the contribution of natural philosophers, the ‘sons of Genius’, to the flourishing of culture and humanity.

Translation is only one aspect of viewing Maria as a European writer who participated in pan-European literary networks. Her epistolary novel, Leonora (1807), for example, was written in response to Madame de Staël’s (1766-1817) literary sensation Delphine which appeared in print while Maria was staying in Paris in 1802. You may recall from our July blog, that Byron counted both Maria and de Staël amongst the ‘literary lions’ of the age. Their cross-channel, contemporary success is integral rather than incidental to this description. Unlike Jane Austen (today the most famous novelist of the early nineteenth century) whose novels are set in England, Maria used locations across Ireland, England and France, the latter being the (partial) setting for both Leonora (1807) and Ormond (1817), as well as further afield – ‘The Grateful Negro’ is set in the West Indies. Several of her near-contemporaries, including Helen Maria Williams (1759–1827), Charlotte Smith (1749–1806), and Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) also depicted scenes abroad in their writing.

As we have seen on numerous occasions throughout this blog series, the Edgeworth family were a ministry of all the talents. Maria’s literary depictions of France were therefore not the only representations of abroad. There are several drawings of Irish, French and Swiss views in the Edgeworth papers collection, drawn by various members of the family (MS. Eng. misc. c. 901 fols. 90-136). The family travelled further still: during Michael Packenham’s journey to India in 1831-1832 he produced a series of pencil and ink drawings of India in the ‘No. 1 Madras Sketchbook’ (MS. Eng. misc. g. 356) and five poems (MS. Eng. misc. c. 898 fols. 31-5). These drawings and writings are a testament not only to their artistic endeavours but also to the family’s travels.

Image from No. 1 Madras Sketchbook (MS. Eng. misc. g. 356)

Image from No. 1 Madras Sketchbook (MS. Eng. misc. g. 356)

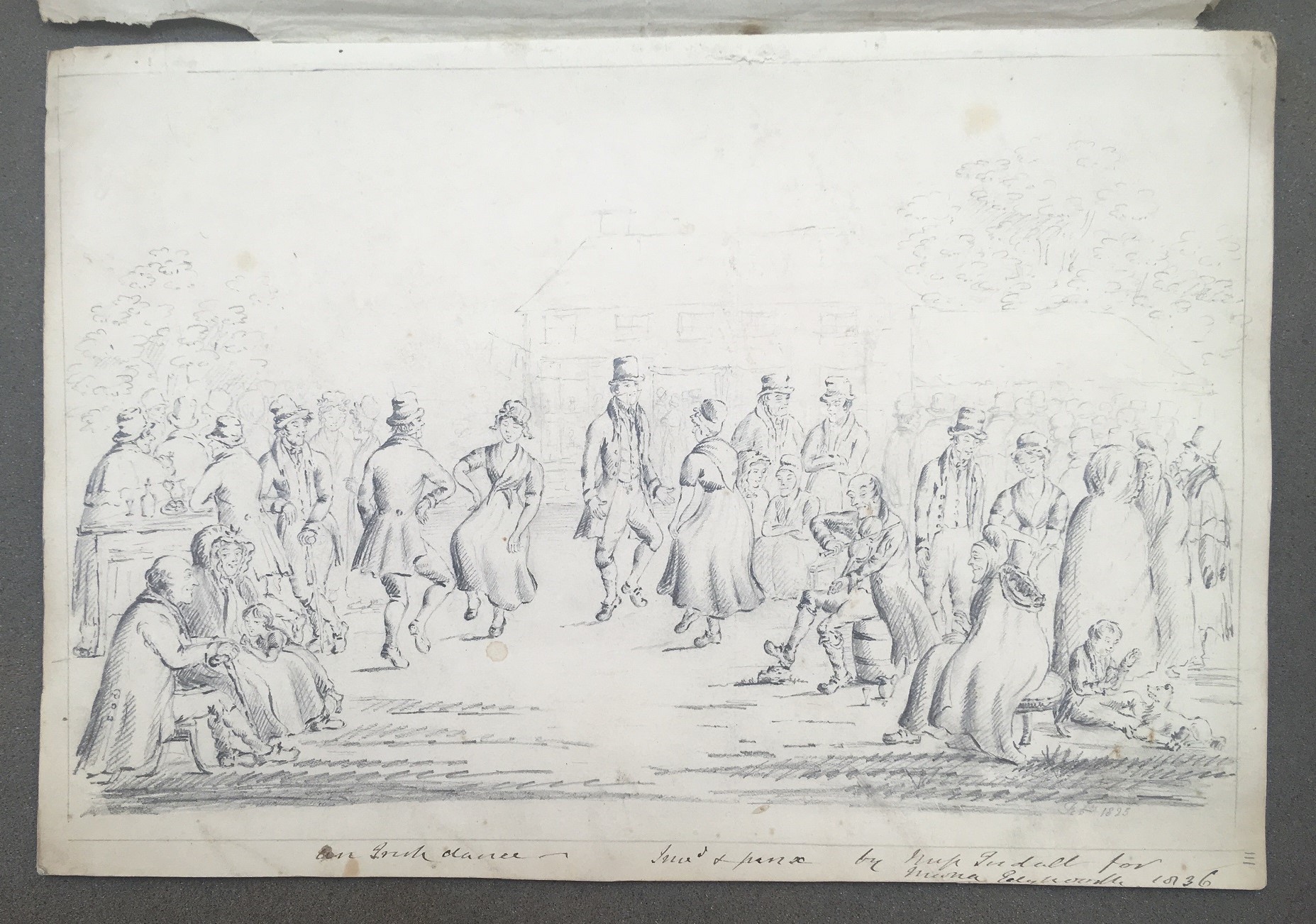

Whilst the letter of September 1819 speaks of the family’s friendship and literary connections in France, Maria’s popularity in France and the influence of French writers (especially female) on her own work, it also demonstrates the Edgeworths’ attachment to the cultural pleasures of the Irish Catholic tenants to which they lived in such close proximity. On the way back from a drive in their landau with Mrs and Miss Carr (visiting acquaintances from England whom we encountered in our April blog), they stop to join an appreciative audience in the sunshine as a fiddler plays for dancers in ‘all the vivacity & graces of an Irish gig’. The scene reminded Maria of her sister’s Charlotte’s drawings of similar scenes, which had been engraved for inclusion in the forthcoming memoir of their father that Maria had written, Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1820). It was a scene that the Edgeworths were particular fond of – here is another similar drawing in the Edgeworth papers of an Irish dance, drawn for Maria by a female acquaintance in 1836.

Irish Scene, drawing in pen and ink, MS. Eng. misc. c. 901 fol. 111

Irish Scene, drawing in pen and ink, MS. Eng. misc. c. 901 fol. 111

Fragment of MS. Eng. lett. c. 704 fol. 7v

Fragment of MS. Eng. lett. c. 704 fol. 7v

In this month of September 2019, as Great Britain is on the cusp of separation from these two European countries of Ireland and France, a family letter of two hundred years ago reminds us of a long history of artistic and intellectual exchange. Of course, historically, relationships between France, England and Ireland have often been troubled by conflict, claims and counterclaims of sovereignty and autonomy. But we hear in Frances and Maria Edgeworth’s collaborative letter a desire for connection, a sense that there is much to be learnt and enjoyed in acts of translation not just of languages but also of cultures.

Anna Louise Senkiw

Footnotes:

(1) “I will return near the end of August to Paris – or maybe to Passy and that is why I hope to enjoy again the society of Mr and Mrs Sneyd. I like Mrs Sneyd very much. She seems kind and sensitive – the two attributes that are essential to women – and which the Edgeworth women I have had the pleasure to know possess especially” [translated by Ros Ballaster].

(2) See Gillian Dow (ed.), Translators, Interpreters, Mediators: Women Writers 1700-1900 and Marilyn Butler, Maria Edgeworth: A Literary Biography.

References:

Marilyn Butler, Maria Edgeworth: A Literary Biography (Clarendon Press, 1972).

Gillian Dow (ed.), Translators, Interpreters, Mediators: Women Writers 1700-1900 (Peter Lang, 2007).

Susan Manly, Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849), available at: https://chawtonhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Maria-Edgeworth.pdf

Clíona Ó Gallchoir, Maria Edgeworth: Women, Enlightenment and Nation (University College Dublin Press, 2005).