This month’s University Archives blog looks at some of the stranger annotations which appear in the University’s records over the centuries. Administrative records of any organisation can be fairly dry affairs. They were created because a job needed doing and the University’s officers and administrators, in the main, dutifully carried our their tasks. Many of the records in the Archives here, however, show that the people who wrote them were not that different from us today. They got bored at meetings, they criticised their colleagues, and they couldn’t resist a joke at someone else’s expense.

As well as recording the important business of the day, some records can contain extra notes and annotations in the margins, or sometimes right in the middle of the text, which add unexpected details. Although mostly mere scribbles and doodles (‘marginalia’ seems too grandiose a term for these), some of the notes are making a very different point. The following is just a very small selection of what we’ve found.

One of the earliest registers of University business in the Archives is a register kept by the Chancellor. Known as the Chancellor’s Register (Registrum Cancellarii), it was maintained by successive Chancellors from 1435 to 1469 and contained a range of business with which they, or their specially-appointed commissaries (deputies) personally dealt. The Chancellor’s powers were wide and as well as being head of the University, he also had to act as judge, magistrate and keeper of the peace in Oxford.

Throughout the register there are little pointing hands drawn in the margins, directing the reader to something important. Known as manicules, these were commonly used for centuries as a way of highlighting key points or interesting parts of a text, much like the fifteenth-century equivalent of a post-it note.

In other places, there are more elaborate doodles which appear to serve no purpose whatsoever other than to quell the boredom of the writer. On one page, written by one of the Chancellor’s commissaries, John Beek, during his deputising for the Chancellor in September 1451, there is an elaborate circular drawing. This must have taken some time to do as it is carefully drawn. Perhaps the business that day was particularly dull?

Doodle from the Chancellor’s Register, 1451 (from OUA/Hyp/A/1)

Some records in the Archives also show evidence of officers’ recordkeeping skills being criticised by their colleagues. A Register of Congregation contains a terse exchange of 1580 written in the margin in which the Registrar (and writer of the register) Richard Cullen receives a complaint from an unhappy anonymous critic. The note is written next to a blank list of inceptors (those who were proceeding to higher degrees) in Theology, Civil Law and Medicine. The names haven’t been filled in yet. The anonymous critic starts things off, complaining about the emptiness of the list:

‘Mr Cullen, you must use to make your book more perfit and not leave their names owt so long til thei be quite forgoten’

Richard Cullen retaliates, firmly passing the blame onto someone else, namely one of the University’s Bedels:

‘not forgotten but the bedell not paynge of me for regestring this act hath dune me injurye and so you’

The matter seems not to have been resolved within the pages of the register. The entries remained empty. Let’s hope the people receiving their higher degrees were not forgotten as a result.

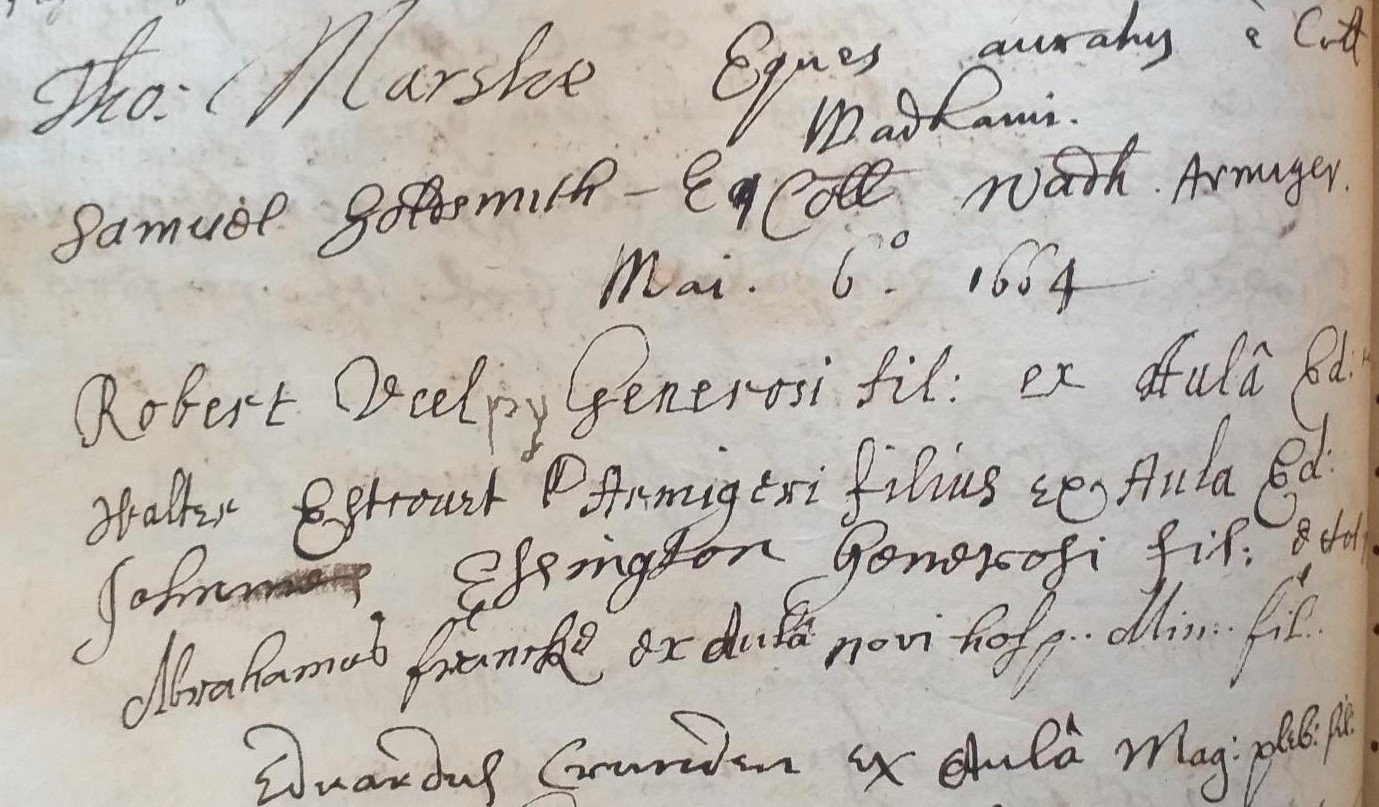

Less commonly, the University’s records have been annotated to make a joke. Robert Veel, who matriculated from St Edmund Hall on 6 May 1664, was the victim of such a joke. Robert signed his name in the University’s subscription register, as every student was required to do at that time, confirming his assent to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England.

Someone, we don’t know who, then thought it hilarious to write in the word ‘py’ after Robert’s surname, so he is now listed for posterity as Robert Veel py (ie veal pie). It looks as if the comedy addition to the register was done at pretty much the same time as Robert wrote his name, but we don’t know whether it was a bored administrator who snuck the joke in, or perhaps one of the students signing their name further down the page after Robert who saw an opportunity. Either way, the joke made it into Joseph Foster’s Alumni Oxonienses, the multi-volume register of members of the University up to 1888, published in the late nineteenth century. There, Foster rather cheerlessly describes the insertion ‘doubtless as a jest’.

It will be interesting to see how the transition from paper to digital records in the University affects the survival of doodles and other annotations like this in the future. Born-digital records offer many benefits, but they could, rather sadly, hail the demise of such notes in the margin.