By Nic Madge.

This is the second in a series of posts by researchers drawing on the archive of the Anti-Slavery Society, part of the Bodleian’s We Are Our History project.

The Putumayo Atrocities

The work of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society in exposing the Putumayo Atrocities is well known. In 1907, W. E. Hardenburg, a U.S. railway engineer, left Buenaventura, on Colombia’s Pacific coast, to travel across South America to the Atlantic. While descending the Putumayo River, he was captured and detained by agents of the British registered Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company. He discovered that “peaceful Indians were put to work at rubber-gathering without payment, without food, in nakedness; … their women were stolen, ravished, and murdered; [they] were flogged until their bones were laid bare when they failed to bring in a sufficient quota of rubber or attempted to escape, were left to die with their wounds festering with maggots, and their bodies were used as food for the agents’ dogs; … flogging of men, women, and children was the least of the tortures employed; [they] were mutilated in the stocks, cut to pieces with machetes, crucified head downwards, their limbs lopped off, target-shooting for diversion was practised upon them, and … they were soused in petroleum and burned alive, both men and women.” (Hardenburg The Putumayo, The Devil’s Paradise page 29)

Hardenburg escaped and travelled to Britain where he contacted the Anti-Slavery Society. John Hobbis Harris, the Society’s Organising Secretary, raised the issue with the Foreign Office and arranged for questions to be asked in the House of Commons. As a result of the Society’s pressure, the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, appointed diplomat Roger Casement to conduct an enquiry. Casement travelled to Peru in July 1910. His report was finalised in January 1911, but only laid before Parliament in 1912. He found that the worst accounts were confirmed. The company’s agents had enslaved “the whole native population … by intimidation and brutality on a scale and of a kind which forbid description.” Sometimes, victims were pegged-out on the ground. At other times, they were flogged in stocks. Rubber “pirates” were “shot at sight”. Private rubber wars recalled “the feudal conflicts of the early Middle Ages.”

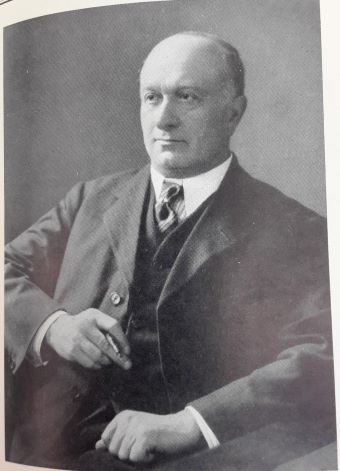

John Hobbis Harris on the front cover of ‘The Anti-Slavery Reporter and Aborigines’ Friend’ (Series V, Volume 30, number 2, July 1940). Shelfmark: 100.221 r. 16.

There was outrage in the British press that representatives of a British company should act in this way. In August 1912, Canon Hensley Henson, who had attended an Anti-Slavery Society committee meeting, used his Sunday sermon in Westminster Abbey to condemn the atrocities. Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle and Lord Rothschild contributed to a Putumayo Mission Fund organised by the Duke of Norfolk. On 20 November 1912, Travers Buxton, the Society’s secretary, and John Hobbis Harris both gave evidence to a House of Commons select committee which was considering whether the British directors of the company had any knowledge of the atrocities. The Anti-Slavery Society vigorously pursued the issue; sending a delegation to see the Prime Minister; instituting proceedings in the Chancery Division to remove the liquidator of the Peruvian Amazon Company; and drafting amendments to anti-slavery legislation to enable prosecutions to be brought in England for acts committed overseas.

The Prime Minister, Lord Asquith, referred to “the exceptional circumstances” of the Putumayo allegations. Francis Dyke Acland, Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, gave an assurance that, “No outrages of any kind were committed by Englishmen.” However, these opinions were disputed by British explorer

Colonel Percy Fawcett, who wrote to The Times suggesting that the rubber industry in “the whole of forest Peru” should be investigated. It was “obviously improbable that such scandals are confined to one of the better known and relatively more accessible affluents of the Amazon. Other tribes are held up to slavery besides those of the Putumayo.” Fawcett’s view was that “real slavery was the rule (though covered by quasi-legal formalities)”.

A Great Uncle and Colonel Percy Fawcett

My research into Peruvian rubber extraction has focussed upon another British company, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate, and its enslavement of indigenous people a thousand miles from the Putumayo, at the opposite end of Peru. My interest was triggered by a letter from a great uncle, written to one of his daughters in 1953. He commented on Fawcett’s book Exploration Fawcett and mentioned that Fawcett and his companions had stayed with him between 1910 and 1912 at San Carlos and Marte, two barracas (rubber collection stations) on the Tambopata river. I never met my great uncle and knew little about him, except that he had left Manchester at the beginning of the twentieth century and, apart from fighting in World War 1, spent the rest of his life in South America. Exploration Fawcett refers to Fawcett’s work on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society delineating the border between Peru. He travelled with James Murray, a Scottish biologist, who had accompanied Ernest Shackleton on his 1907-1909 Nimrod expedition to the Antarctic, and Corporal Henry Costin, a former army gymnastic instructor. However, his book gives little detail about San Carlos and Marte. Was there more information in the diaries and letters of Fawcett and his party?

Fawcett’s diaries are now held by the Torquay Museum. There is a transcript of Murray’s diary in the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. I obtained copies of some of Costin’s letters from his daughter in Australia. I found records of the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate and their British agents, Antony Gibbs and William Ricketts, in the National Archives, Kew, the London Metropolitan Archives and the Archivo General de la Nación del Perú in Lima. Murray mentioned my great uncle briefly, but, more significantly, these sources gave a vivid and disturbing description of the activities of the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate.

Enganche por Deudas

Tambopata Rubber used between 300 and 500 indigenous workers, mainly picadores (choppers) and peones (general labourers) to collect rubber. Many came from the Peruvian and Bolivian Altiplano. Some were members of the local Ese Eja community who had been pressed into service. Like many other companies in Peru, Tambopata Rubber operated a system of enganche por deudas (literally “hooking by debts”). It was bonded labour, often forced. Employers advanced money or some other benefit (transport, accommodation and/or food) which became a debt which workers had to pay off by their labour. It was common for workers to be forced or tricked into this arrangement. Illiterate peones found themselves bound by written contacts which they had signed or marked with thumb prints, but did not understand. The necessaries provided in return for their employment (food, accommodation) were normally over-priced. Debts tended to increase not reduce. Under Peruvian law, a worker was legally obliged to stay with his employer until the debt was paid off. Often that was impossible. Some of the labourers had been transferred over to Tambopata Rubber from the previous owner of the barracas, a German called Carlos Franck. Effectively, this was the sale of human beings tied to the barracas by their debts. The Franck and Tambopata Rubber contracts provided that the workers would pay interest at the rate of 2% per month in the event of any breach of contract; renounced the legal code of their own area; and secured the performance of their enganche obligations with their “person and the best of their goods.” In other words, enganche was slavery.

The workers were paid on Sundays with lead fichas (tokens) which could only be used in the company almacenes (stores). Prices for food at San Carlos were high and the picadores were routinely swindled over the rubber they brought in.

Tambopata Rubber sought to recover the debts of any workers who fled against their property and via sub-prefects and any new employers. Even in death, workers were bound by debt. On 26 September 1910, a guard who had been working at Marte for over two years, died of a brain haemorrhage. Franck wrote to Lawrence, the local manager, “He has left a wife and three orphaned children. The family of the deceased overwhelm me with their complaints and cries and they demand that I give them at least something to be able to support their little offspring. … I would like you to tell me if the deceased has left any balance so that his family can be protected.”

Lawrence replied, “This ill-fated employee has not left any balance in his favour. On the contrary, he has died owing us a sum.” The Tambopata Rubber Syndicate actively pursued relatives of other workers who died to recover outstanding enganche debts – on at least one occasion forcing them to sell their home.

Food and Health

Fawcett and Murray noted that food at the barracas was always in short supply. In 1910, Fawcett found Marte “in a state of starvation” with only a quart of maize left in the stores. The labourers had existed on leaves and grass for some time. By 1911, there were no provisions at all at Marte and there were often periods when workers went for days without any food. That year, four or five men died of starvation. The Marte manager led raiding parties to rob the banana trees of the Ese Eja in a neighbouring valley.

Given the climate, predatory insects, poor nutrition, the lack of sanitation and the absence of any doctor or medical assistance in the region, it was inevitable that there would be serious health problems on the two barracas. The company’s own records frequently refer to illness and death. In 1910, ten percent of Tambopata Rubber Syndicate workers died as a result of disease and hunger. Fawcett described a group of labourers from Marte arriving at San Carlos as “a grizzly, weak, thin, diseased crew.” There were many cases of malaria and beri beri. In 1911, there was a severe outbreak of fever at Marte. Fawcett described some thirty indigenous workers lying “in a filthy shed … in various stages of collapse, putrid with boils and other disorders.”

Oppression on the barracas

Severe beating was common on rubber estates. Fawcett, Murray and Costin all noted with disapproval that Lawrence frequently flogged workers. Murray stated, “Flogging is practiced at San Carlos, though we could not know to what extent, as a good face is put on things for our benefit. Lawrence, however, uses a whip on the house ‘boys’ and often without justification. For instance, Costin’s pistol was stolen. Lawrence whipped the three house-boys, without having any reason to suspect them.”

Fawcett noted, “In Peru the punishment for whacking an Indian is some years of prison but the Indian has to put up 500 Peruvian soles to state his case.” He described how one of the bookkeepers at San Carlos beat an indigenous worker so badly that complaint was made to the provincial authorities. However, in accordance with the law, the bookkeeper insisted that the victim deposit 500 soles against the expenses of the prosecution. He was unable to produce that sum and instead the bookkeeper accused him of calumny. He was imprisoned for eight months, but died after four months.

Lawrence “bought” people. He boasted to Murray that he bought a woman he kept at San Carlos (despite having a wife in La Paz) for 150 bolivianos. Fawcett wrote, “The savages bring in their children to sell frequently.” On one occasion, Lawrence exchanged two guns, each worth nine shillings and six pence (47½ pence) for two small boys.

From time to time, the workers rebelled against this regime. On 4 September 1909, there was “a serious insurrection” involving one hundred workers at Marte. They fled, after burning the almacen and account books. Tambopata Rubber’s managers, with the help of the local authorities, managed to capture and return most of them. One of the workers who returned surrendered and went down on his knees, begging for forgiveness. A manager shot and killed him as he knelt.

Denunciation of the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate

The final pieces in my research jig-saw were the records of the Anti-Slavery Society at the Bodleian which contain press-cuttings and correspondence with the Peruvian Asociación Pro Indígena. They recount how, in 1910, three picadores managed to escape from Tambopata Rubber’s barracas. They complained about their treatment to the manager of the Inca Rubber Company at Cojata. He informed Pedro Zulen, Secretary of the Asociación Pro Indígena, who wrote to the Puno Prefect:

“Manuel Machicao, Mariano Tito, and Modesto Villa, all three natives of the Department of Puno, have been subjected to corporal punishment, Machiao and Villa at the barraca “Marte” and Tito at the barraca “San Carlos”, which belongs to the Sindicate “Tambopata Rubber”. The … workmen were punished for the least reason. … A certain Braulio Peñaranda is named as the chief tormentor of the labourers; the provision of food is not sufficient for the people, who live on half-rations, and are forced to work from 6 in the morning to 6 in the afternoon, so that many get ill with forest diseases.”

The Asociación Pro Indígena petitioned for workers to be allowed to leave the barracas because “at present the labourers cannot leave … whether or not they owe a debt, but are kept like slaves, condemned to die for want of resources, without receiving any aid”.

This issue was discussed at an Asociación Pro Indígena meeting on 20 January 1911. It resolved to send details to the Anti-Slavery Society under the title “La Esclavitud en la Montaña”. (Due to, in Pedro Zulen’s words, “an involuntary clerical error” publicity of the allegations wrongly named Inambari Para Rubber Estates as the company responsible, not the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate.) The allegations were published in El Deber Pro-Indígena, the Asociación’s newspaper, and repeated in the Peruvian newspapers El Comercio and La Prensa. El Comercio stated that the “abuses reached the point of ripping indigenous people out of their homes to enslave them in the montaña.” The London Times published a telegram from its Lima Correspondent stating that the President of the Asociación petitioned the Peruvian Government to punish and put a stop to the abuses. In London, Ernest Bartlett, Tambopata Rubber’s Company Secretary, wrote to the Under Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, stating, “the alleged ill-treatment of natives can hardly be taken seriously”; “there is not an iota of truth” in the accusation; the allegations were driven by internal “political rather than humanitarian considerations”; and that he had “no doubt nothing in the nature of an outrage has taken place on [their] property”. Just like Peruvian Amazon’s denial of the Putumayo Atrocities, that attempted rebuttal is not credible in the face of the independent evidence of Fawcett, Murray and Costin.

During 1911, the Anti-Slavery Society received reports of “conditions of debt slavery prevailing throughout Peru”, but in the end only actively pursued the Putumayo Atrocities. The complication of Zulen’s “involuntary clerical error” naming the wrong company delayed its investigation into the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate and its Committee concluded that there was insufficient information to enable it to make any definite recommendation.

Postscript

In any event, by 1911, the Amazonian rubber boom was over. Rubber prices were plummeting and it was clear that the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate project was economically unsustainable. The cost of producing rubber was three times higher in South America than in the Far East. Transport was too difficult and too costly. Despite the enslavement of indigenous workers, there was a shortage of labour. There was never sufficient food for the workers. Latex could only be extracted from the local species of rubber tree by felling, rather than tapping, meaning that picadores had to travel further and further to find rubber. The company decided that the barracas could not be made financially viable and abandoned them in 1913. In December 1913, a shareholders’ meeting passed a resolution formally winding up the company and appointed a liquidator.

A more detailed version of Nic Madge’s research will be published in the next edition of La Revista de Historia de América (Volume 165, May-August 2023).