The origins of Reading University have been described as being that of a “University of Oxford extension college”. However, to really understand what this means and the nature of the relationship between the two institutions, it’s necessary to first understand Oxford’s push towards “University Extension” in the 1800s, what that term signifies, and the motivating ethos behind it.

The idea of “University extension” was essentially to make a University-level education more affordable and accessible to a greater number of people. The idea first started to gain traction in Oxford in the first half of the nineteenth century, when both the Low and High-Church parties within the University became interested in opening up the University to potential clergymen from poorer backgrounds. The debates about how best to increase access to University-level education rumbled on throughout the century, until they culminated in a meeting, held in Oriel College in 1865 to “consider the question of the Extension of the University”. Many of the resulting sub-committees looked at options for Oxford itself (such as new colleges or permitting non-collegiate students). However, some of the sub-committees investigated how to provide such an education “outside the walls” of Oxford, responding to a national swell in demand from the country’s growing towns and cities. Although difficult to imagine now, Oxford was one of only nine universities in the UK in 1860.

The result of these investigations came in 1878, with the formation of a Standing Committee of the Delegacy for Local Examinations to provide “lectures and teaching in the large towns of England and Wales” (reconstituted as a separate Delegacy, the Delegacy for the Extension of Teaching Beyond the limits of the University, in 1892). The aim of this committee was not to create outposts of Oxford across the country, but an outreach programme, encouraging the growth of local centres managed locally, which would provide high-quality educational opportunities.

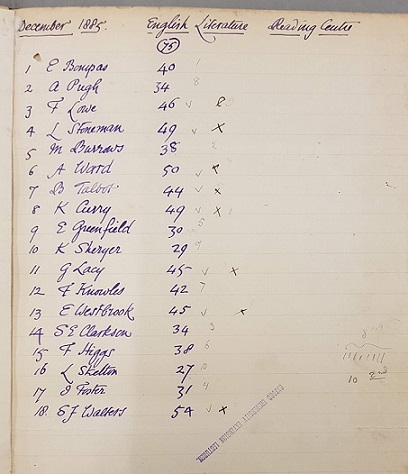

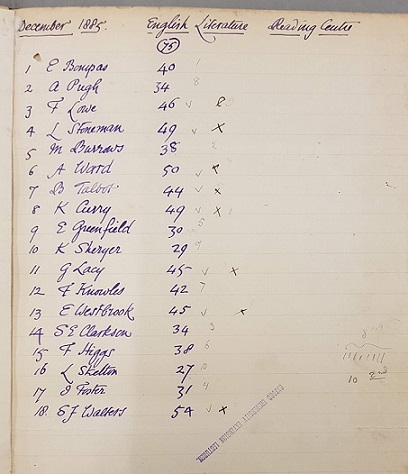

Extract from Extension Lectures: Lecturers’ and Examiners’ Reports. 1885-1939 showing the first class held by the Delegacy at Reading (OUA/CE 3/28/1)

Reading was one of the earliest such Extension Centres, starting life in 1885. The first lectures, held in the evenings and aimed at a mature audience, focused primarily on English Literature. Looking at other such initiatives in the Reading area, it’s unsurprising that the Delegacy’s work began so early in Reading. There was a clear thirst for adult education in the town. Classes in “the Arts” (which we’d now refer to as the Humanities), run by the Science and Art Department (a subdivision of the Government’s Board of Trade) had been operating from West Street, Reading, since 1860.

Yet, the idea of building to house these lectures, and provide a focus for adult education in the town came not from the Government, nor from Oxford. Instead, Walter Palmer, a local biscuit manufacturer and President of the Reading University Extension Association in 1891, made the suggestion. This local initiative clearly demonstrated the town’s commitment to the cause, and the academics in Oxford involved with the delegacy were keen to support the scheme. After a little “behind the scenes” campaigning, Christ Church College (home to many of those involved with the Extension Delegacy) wrote to the Reading Association, offering the services of H J Mackinder (an academic at Christ Church, specialising in Geography) “with a view to giving system and completeness” to the work of the Reading University Extension Centre and “for the advancement, the co-ordination and the deepening of study.” The offer was unanimously accepted in Reading, and when the doors of “The University Extension College in conjunction with the Schools of Science and Art, Reading” was opened for the first time in September 1892, Mackinder was its principal.

Photograph of the first site of the University Extension College – rooms and the vicarage on Valpy Street “bounded on the south by the churchyard of St Lawrence”. Image courtesy of University of Reading, Special Collections, (MS 5305)

In its first year alone, the College had 658 students. No students were full-time, but instead classes were arranged to accommodate the needs of the working populace of the town, being hosted in the evenings or on Saturdays. The space afforded to the classes allowed them to increase in range. The Oxford Delegacy and the Government Science and Art department continued to offer a variety of courses such as chemistry, biology electricity, mathematics, and art but these were supplemented with more overtly practical and vocational courses, such as Pitman’s Speed Certificates in typing and classes in machine drawing and wood carving. This variety reflected Reading’s aim to design a curriculum that would “fuse university training (producing thinkers) with technical training (producing the adept).”

This successful novel approach from Reading, of bringing together different locally run initiatives within a central hub, fast attracted other participants. For example, by 1893, the College offered training approved by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons. However, a core issue remained in that, under the legislation of the time, as a local college, Reading had little power to issue its own qualifications. Thus, when Reading made its biggest gain to date – a new department of agriculture, supported by the surrounding County Councils and the Board of Agriculture – it was unable to offer an accompanying recognised qualification.

It was in such cases, as well as running extension classes, that Oxford could provide direct and meaningful support to the College, by offering oversight and university-backing, leading to recognised qualifications. Although the University, at that time, did not offer its own degrees or diplomas in Agriculture, there were those in Oxford with expertise in this area, such as the holders of the Sibthorpian Chair of Rural Economy. Thus, Mackinder was able to advocate for Oxford’s backing of the Agricultural Diplomas issued by Reading, reporting to the Extension Delegacy in 1894 that the Reading College Council would “much prefer this University as Examining Authority, to any other body”. His arguments clearly resonated, as later that year Oxford’s Convocation (the University’s body of MAs and higher degree holders) passed a decree, authorising the issuing of Agricultural Diplomas at Reading by a Joint Committee, made up of representatives of the Oxford University Extension Delegacy and the Reading College Council. These were to be Reading’s first full-time students.

Sketch of the British Dairy Institute, as it opened its new building in Valpy Street, following its move from Aylesbury to Reading in 1893-1894. Image courtesy of University of Reading, Special Collections, (MS 5305)

Again, Reading’s innovation provided a template for further success, as in 1895, the British Dairy Farmers Association agreed to move the Dairy Institute to Reading. This was placed under the aegis of a different Joint Committee – this one made up of representatives of the British Dairy Farmers Association and the Reading University Extension College.

This collaborative relationship continued to operate well for a period of time. Oxford clearly recognised contributions of key individuals in Reading, for example, by conferring the Honorary Degree of MA on Herbert Sutton, Chairman of the Reading College Council. It also demonstrated its understanding of the educational achievements offered by Reading when, in 1899, Convocation voted to grant Reading College “affiliate status”. This status, offered to select universities and colleges in the UK and around the world, gave special privileges to alumni of these institutions when they came to Oxford, recognising that their prior academic achievements could exempt them from certain Oxford requirements (such as first year examinations and so forth).

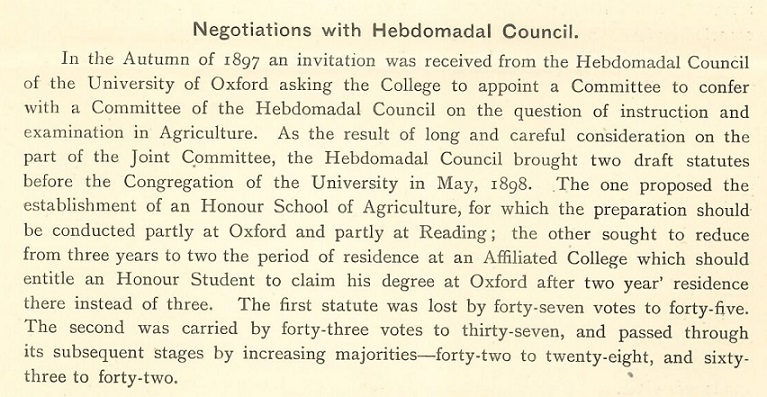

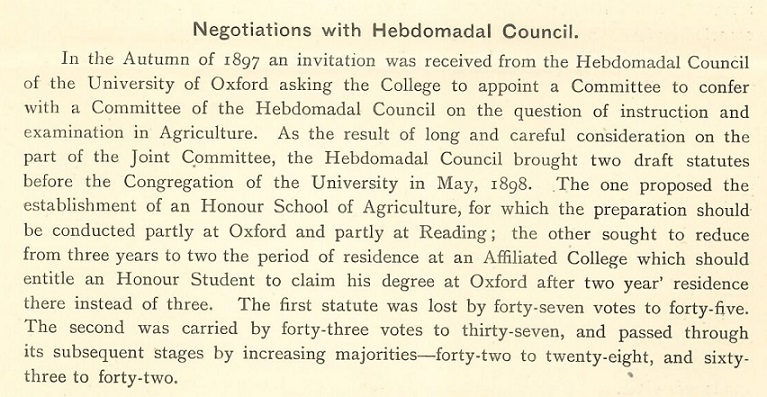

However, there was evidence of growing tension between the two institutions from the late 1890s onwards. It became clear that were those in Oxford who were resistant to the developing interconnection. In 1898, again at the instigation of Mackinder and the Extension Delegacy, Hebdomadal Council (the “cabinet” of the University) proposed the introduction of an honour school of Agricultural Science. Crucially, this degree course would be open to students at Reading, Reading would provide some of the teaching, and Reading would have a say in the curriculum. However, certain individuals within the University campaigned against the involvement of “foreign bodies” in the core business of the University, and this proposal was rejected in Congregation by 47 votes to 45.

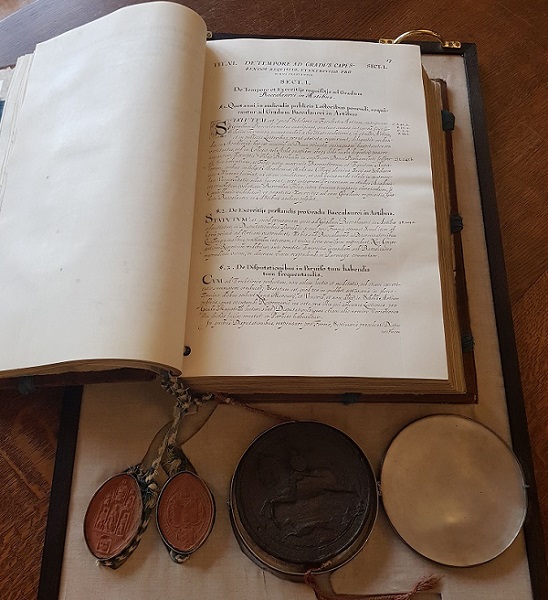

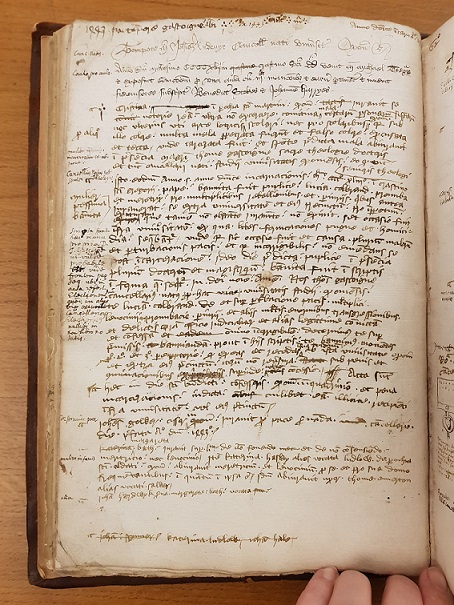

Extract from Reports by H. J. Mackinder on the progress of the University Extension College, Reading; 1895-6, 1896-7, 1897-8, 1898-9. Courtesy of Christ Church Archives (GB xvii.c.1)

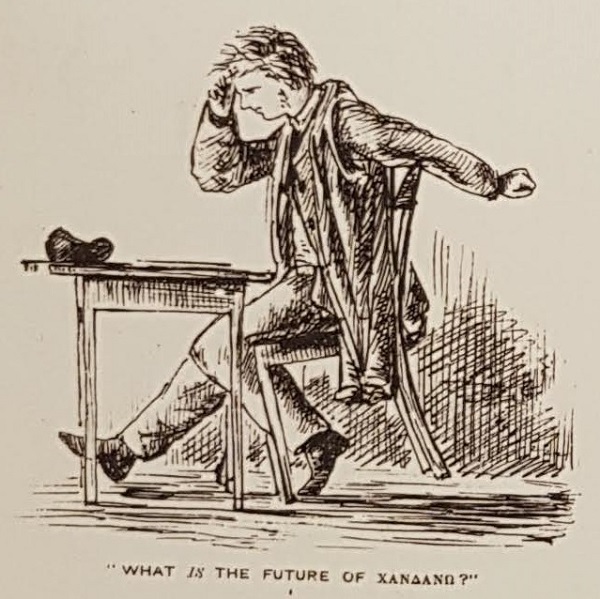

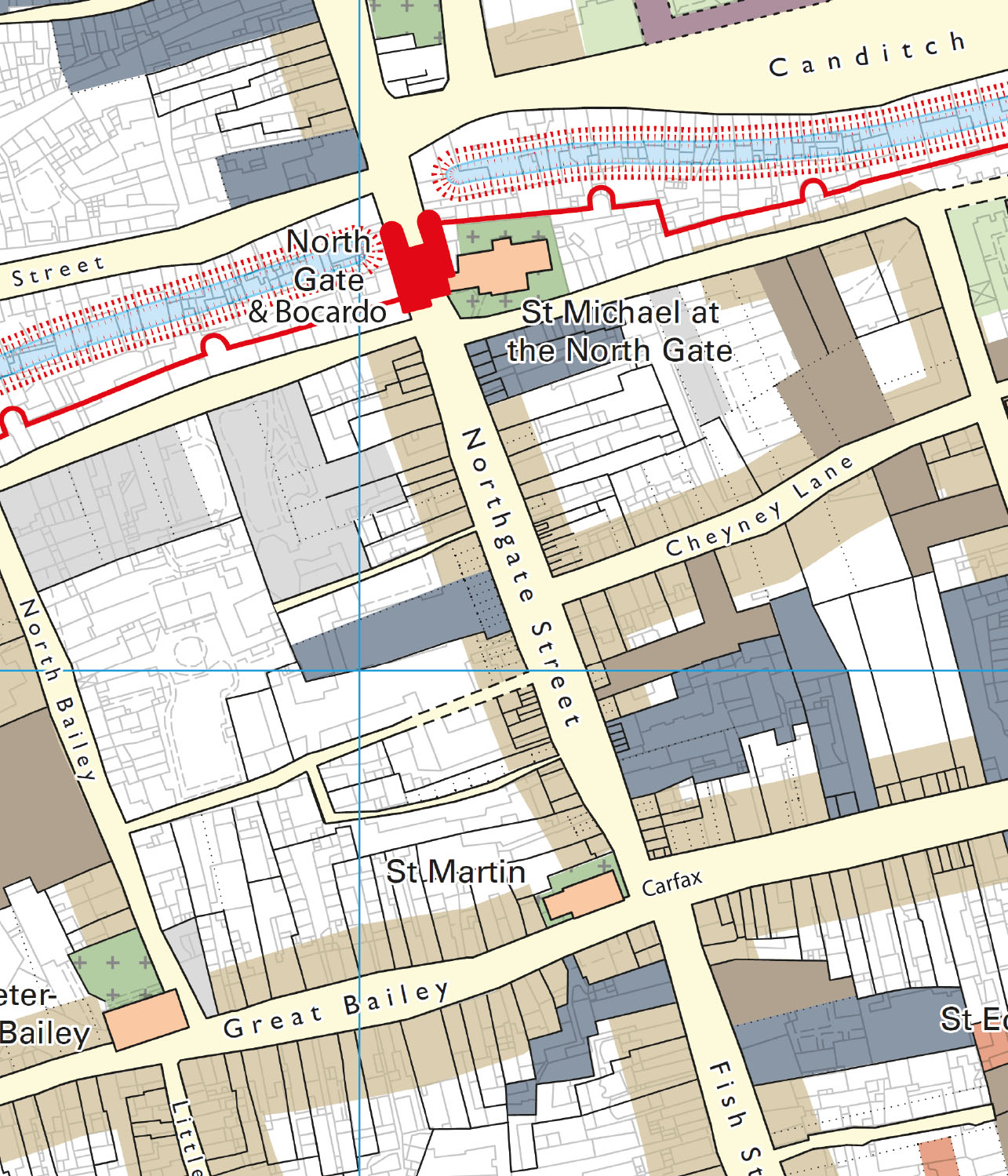

There was, likewise, a growing sense of frustration and of being constrained in Reading, as Oxford degrees were not open to Reading students, largely owing to Oxford’s requirements that all students were to live within a mile and a half of Carfax Tower. WM Childs (a tutor, then Vice-Principal (1900), then Principal (1903) of Reading) wrote “Oxford had always been kind to us; she had helped us, and was still helping us… But her rules of residence, the corner-stone of her system, debarred her from admitting to degrees students attached to a university college twenty-six miles from Carfax”. As such, the only degree courses open to Reading students were those offered by London University, who offered an external degree system to colleges across the country. However, the syllabus and examinations set for these were entirely governed by London, and Reading resented these confines.

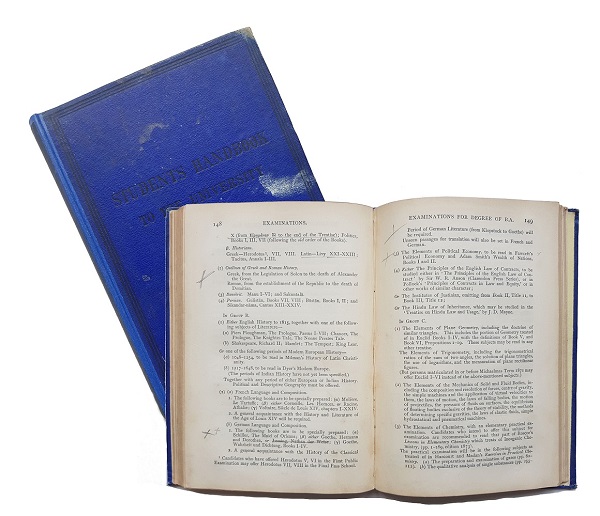

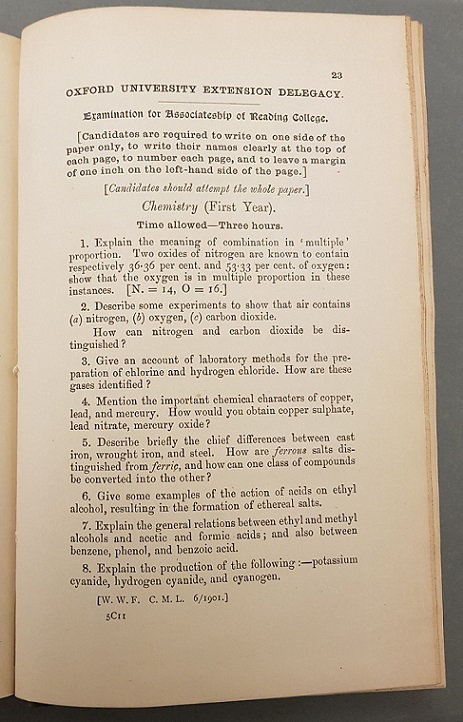

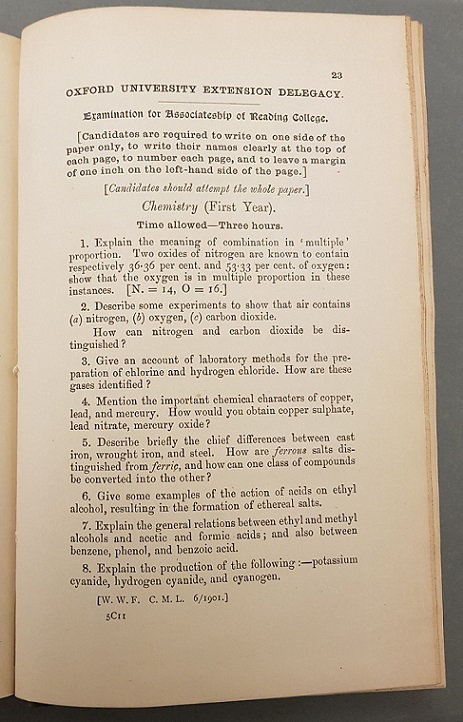

Even the pre-existing collaborative work between Oxford and Reading became the subject of scrutiny. From 1900 the Extension Delegacy had worked with Reading to issue the Reading “Associateship Diploma in Letters or Science”. The Diploma was the result of an extensive period of study – requiring students to attend no fewer than 72 lectures and classes in Science subjects, or 24 lectures and classes in Arts subjects, and pass final examinations in each subject. The examiners were a joint board made up of external examiners from Oxford Delegacy and internal examiners from Reading. Once having obtained a diploma, students could attend a ceremony (akin to a degree ceremony) at Reading, and thus become Associates of the College. The diploma was particularly popular with students at Reading training to be teachers, as the examinations could be counted towards their qualification by the Department of Education. However, in 1905, Reading received correspondence from the Government Board of Education stating that, following their review of teacher training regulations, they would no longer accept the Diploma examinations in lieu of standard teacher training examinations. The crux of the issue appears to have been that the Board of Education saw the diplomas as being issued by the Delegacy and not by the University. Childs appealed to the University’s Hebdomadal Council, writing that “no examination conducted by the Delegacy can meet the present difficulty… the only course which can relieve us of our present difficulties, and satisfy the Board of Education, is that an Examining Board of the University should be appointed”. Thus, in May 1905, Oxford University’s Convocation had to issue a decree clarifying that this was an examination done in partnership with the University (as opposed to solely by the Delegacy) and that the syllabuses were to be approved by Convocation.

Extract from Extension Lectures examination papers 1900-1901 showing the special papers set by the Delegacy for the Reading Diplomas (OUA/CE 3/26/10)

These areas of tension occurred simultaneously with a period of growth at Reading. The College had relocated to a new site on London Road, donated by Alfred Palmer, which would allow for expansion. Construction on the College buildings began early in 1905. As a growing, mature, and successful institution, being fettered by requirements for external interference in both syllabuses and examinations must have been increasingly irksome, and it is clear that Reading began to plan for long-term independence. Some of the changes made to establish Reading as an institution that could operate independently were directly drawn from the Oxford pattern – a tutorial secretary was appointed, a tutorial scheme for teaching students was introduced, internal examinations (called “collections”) were scheduled, as were termly meetings between individual students and the college principal. When Childs succeeded Mackinder as principal of the college in 1903 (thus removing one of the strongest ties between Oxford and Reading), plans for Reading to obtain its own University Charter gathered pace.

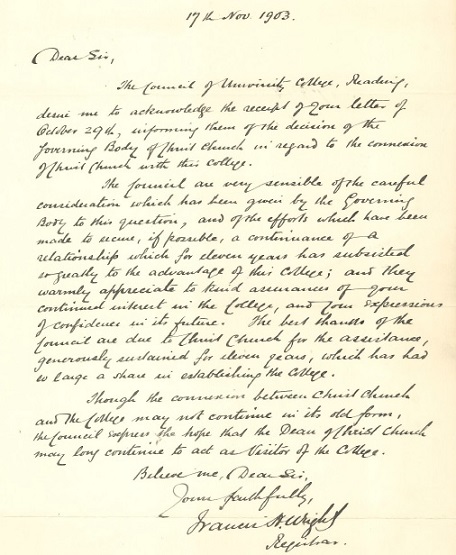

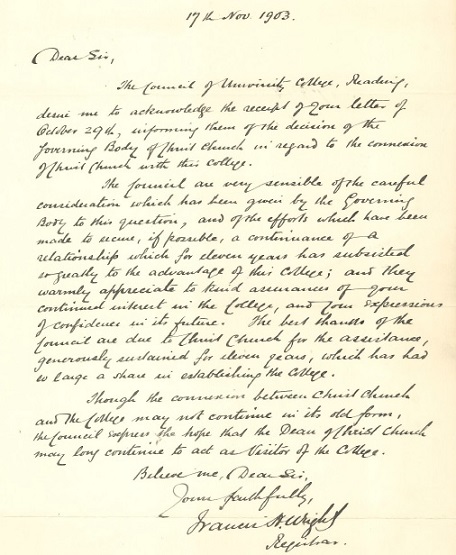

17 November 1903 – Letter from F. H. Wright (Registrar of Reading College) to T. B. Strong (Dean of Christ Church College). Courtesy of Christ Church Archives (GB xvii.c.1).

The letter pictured above is from the Registrar of Reading College, to the Dean of Christ Church College, following Childs’ appointment as Principal of Reading. The first Principal, Mackinder, had been a member of Christ Church, but Childs was not. Thus, Childs’ appointment reflects one of the many examples of Reading’s increasing independence in this period.

Childs wrote “The College had now passed beyond the stage permitting direction from Oxford. That arrangement no longer enabled the Principal to discharge his responsibilities comfortably to himself, or to others” and that if Reading were to become a University “we should be released from the fetters of external examinations, and we should be empowered to shape our own curriculum”.

Preparation for University status, nevertheless, took some time to come to fulfilment. The College had to ensure it had sufficient accommodation for both sexes. In 1905 the College opened St George’s Hostel for female students and in 1908 it opened its new accommodation hall for men (Wantage Hall), which could accommodate 76 students.

An undated photograph of Wantage Hall, modelled on the traditional college quadrangle arrangement. Image courtesy of University of Reading, Special Collections, (MS 5305)

The College also began to focus on the make-up of the student body in preparation for University status, by giving preference in admission to students reading for degrees (offered via the University of London) or those taking other higher courses of study. In 1909, it reorganised its governance constitution to enable members of the Academic Board of the College to be better represented on the Council of the College, and thus more closely resemble the constitution of other universities. However, one of the key issues to resolve was that of funding, and for that, Childs turned to local supporters. To set out his case, and garner support, he published a pamphlet called Statement of the Case for University Independence in January 1920. The pamphlet enumerated the objections of the College to continued “subjection to disabilities born of accident” making clear Reading’s lack of control over the subjects it taught: “A university is one thing; a college is another. A university, for example, grants degrees and controls the curriculum and examinations leading to those degrees. A college can do neither…” Childs’ arguments were clearly met by a receptive audience, and over the next five years, sufficient funds were accumulated to sufficiently endow a new University, with a notable donation by George William Palmer, grandson to the man who had first suggested a college at Reading in 1891. On the 17 March 1926, Reading received its Royal Charter as a University.

Following the award of the charter, Childs published another pamphlet, titled The New University of Reading: Some Ideas for Which it Stands. The pamphlet concludes “And my readers will understand why I mentioned with particular gratitude the kind letters we have received from the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, and from the Dean of Christ Church; for to Christ Church and to Oxford we are proud to be able to trace the original impulse of our own foundation”. Whilst Childs’ acknowledgement is perhaps fair, in that the work of the Oxford Extension Delegacy may have provided an impulse, it is clear from Reading’s history that the sustained work and innovative initiatives that led to Reading’s success really came from the local area. Perhaps a more telling acknowledgement of Reading’s achievements and the “direction” of the debt owed can be found in a form of words that appear in the minutes of the Oxford Extension Delegacy when discussing the development of another centre “suggests the consideration of… the method adopted in the case of Reading”.

With thanks to our colleagues in the Special Collections Service at the University of Reading, especially Sharon Maxwell and Guy Baxter, for their assistance and insight.

Further Sources

Childs, W. M. Making a University : An Account of the University Movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent, 1933.

Childs, W. M. The New University of Reading : Some Ideas for Which It Stands. Reading, 1926.

Goldman, Lawrence. Dons and Workers: Oxford and Adult Education since 1850. Oxford: Clarendon, 1995.

University College, Reading. Statement of the Case for University Independence. 1920.

The records of the Delegacy for the Extension of Teaching Beyond the limits of the University are held by the Oxford University Archives, as part of the records of the Department for Continuing Education. Please contact enquiries@oua.ox.ac.uk for more information.

If you are interested in researching particular individuals who attended Reading in its early days, Reading Special Collections holds the following sources. Please contact specialcollections@reading.ac.uk for more information:

Annual reports and accounts … / University College, Reading.

Holdings: 1892/3-1900/1 – 1924/25.

Journal

Format: Print journals

Calendar and general directory / University Extension College, Reading.

Holdings: 1892/3 – 1897/8.

Journal

Format: Print journals

Calendar / University College, Reading.

Holdings: 1902/3 – 1925/6.

Journal