Today marks the bicentenary of John Hungerford Pollen’s birth. This is the fourth in a series of five blog posts to mark the bicentenary of John Hungerford Pollen whose archive has recently been acquired by the Bodleian Libraries.

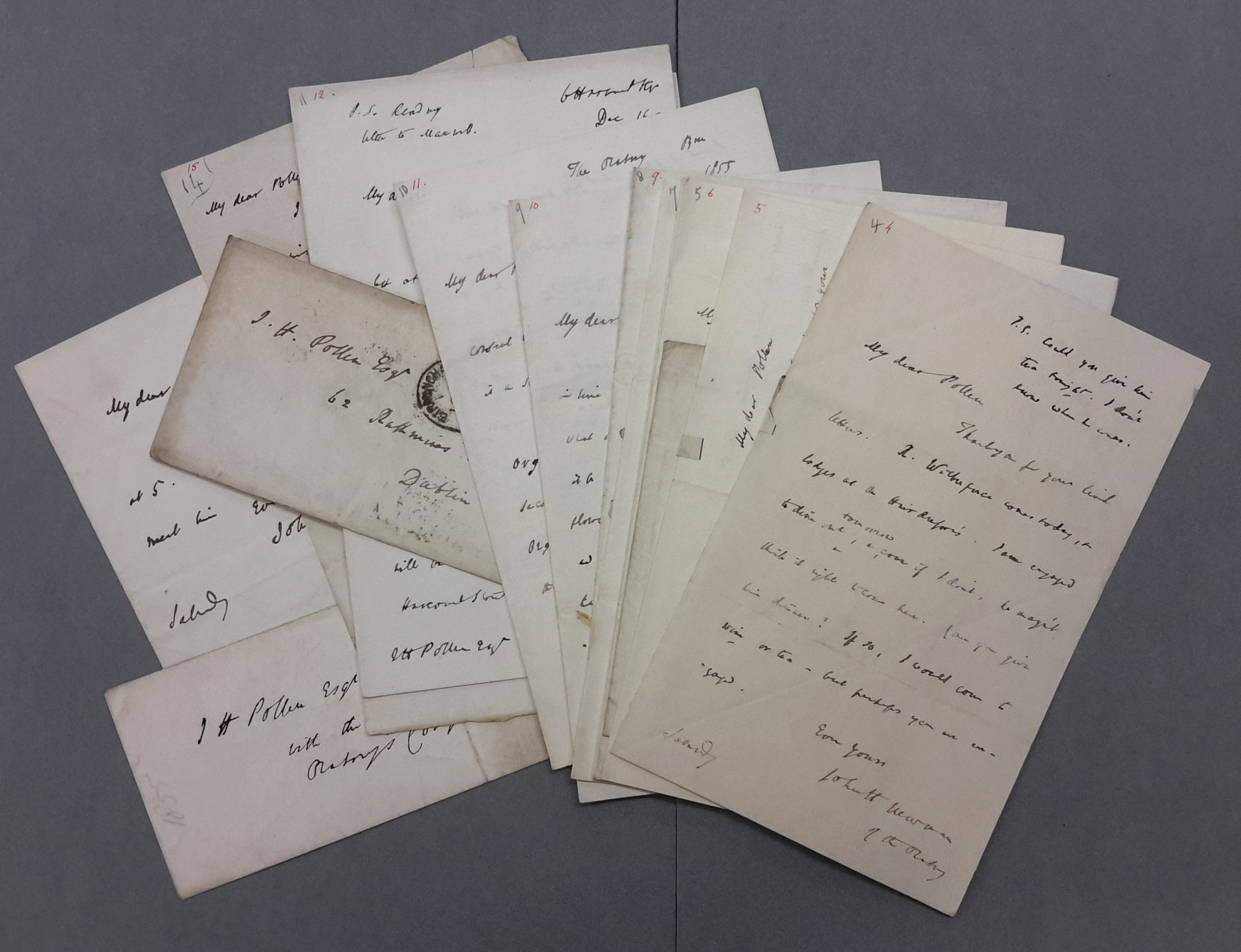

One constant theme throughout John Hungerford Pollen’s life was the ease with which he made friends and the long term commitment that came with Pollen’s friendship. In return, Pollen was offered several life-changing opportunities and we have already seen in this blog series how John Henry Newman and William Makepeace Thackeray both influenced the direction of Pollen’s career. In today’s blog post, we will see how two other friendships changed the course of Pollen’s life.

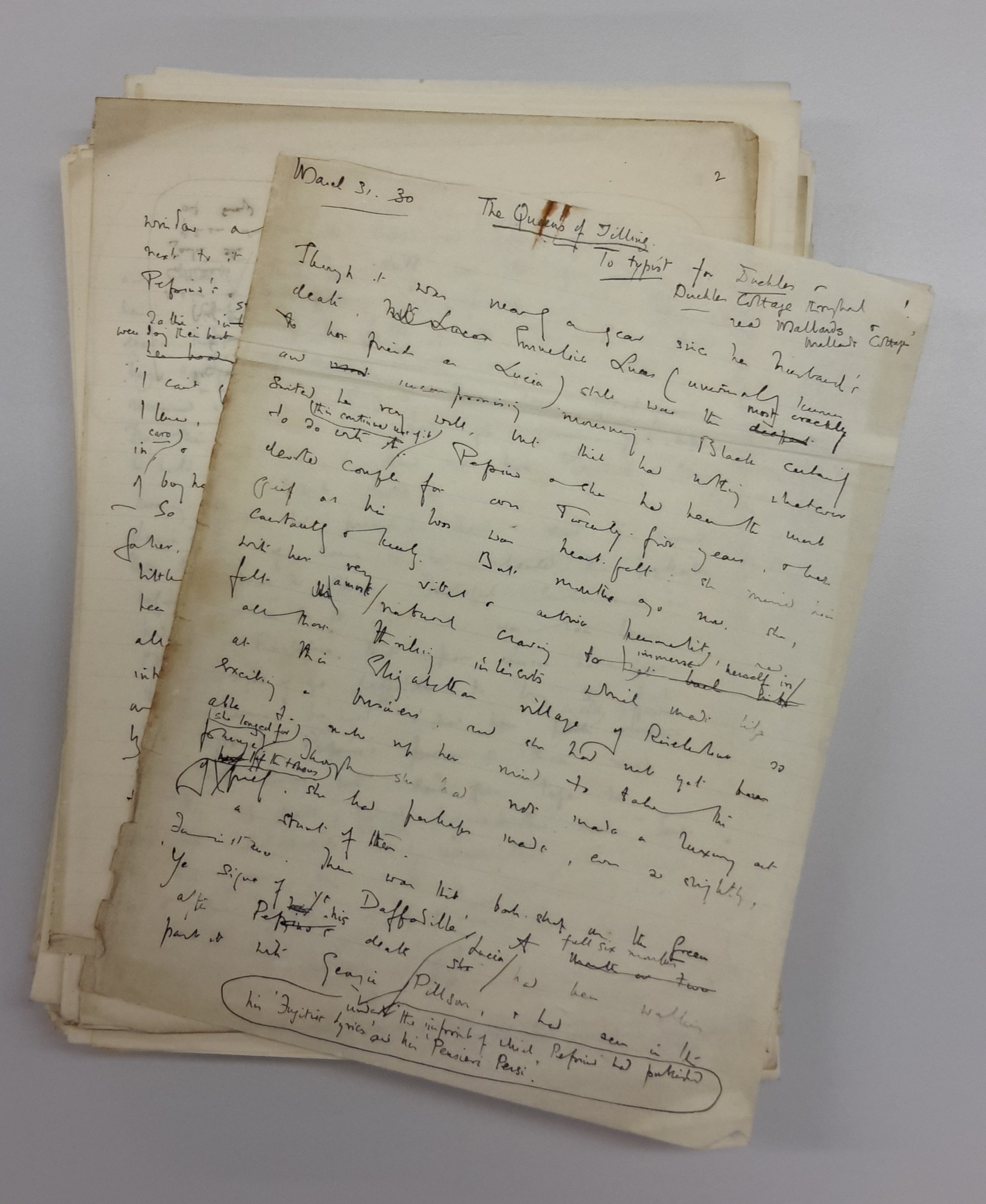

George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon and 3rd Earl de Grey, by George Frederic Watts, oil on canvas, 1895, NPG 1553 © National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon and 3rd Earl de Grey, by George Frederic Watts, oil on canvas, 1895, NPG 1553 © National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

In 1876, Pollen resigned his post at the South Kensington Museum when he was invited to become private secretary to Lord Ripon (1827-1909). Ripon was a fellow Catholic convert and became one of Pollen’s closest friends in later life. In 1880, Ripon was appointed Viceroy of India, a position he was to hold for four years. Though Pollen remained in London during most of this period, he visited India towards the end of the Viceroyalty in 1884. Whilst in India, Pollen commissioned exhibits for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 and also advised the Maharaja of Kuch Behar [Cooch Behar] on the decoration of his palaces.

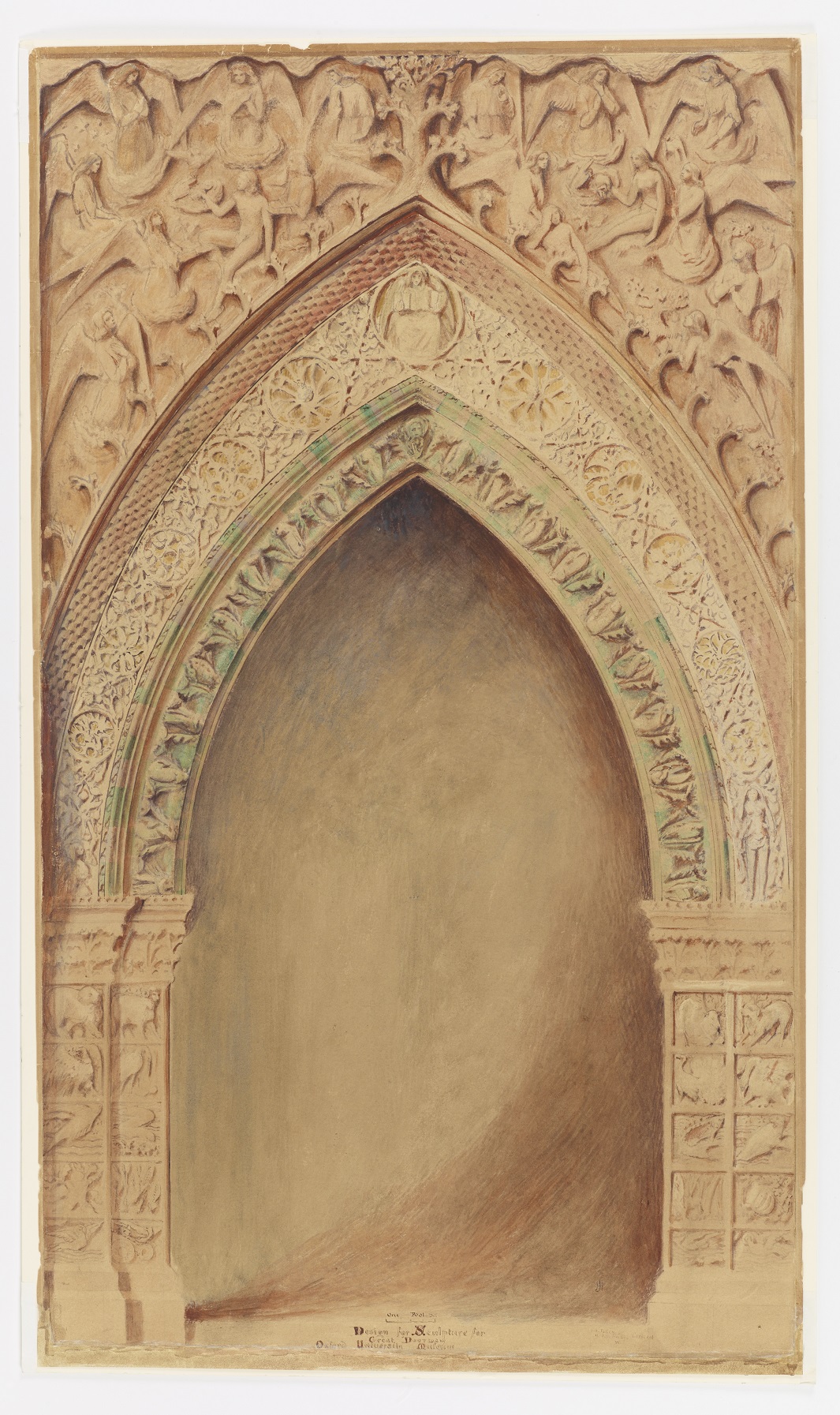

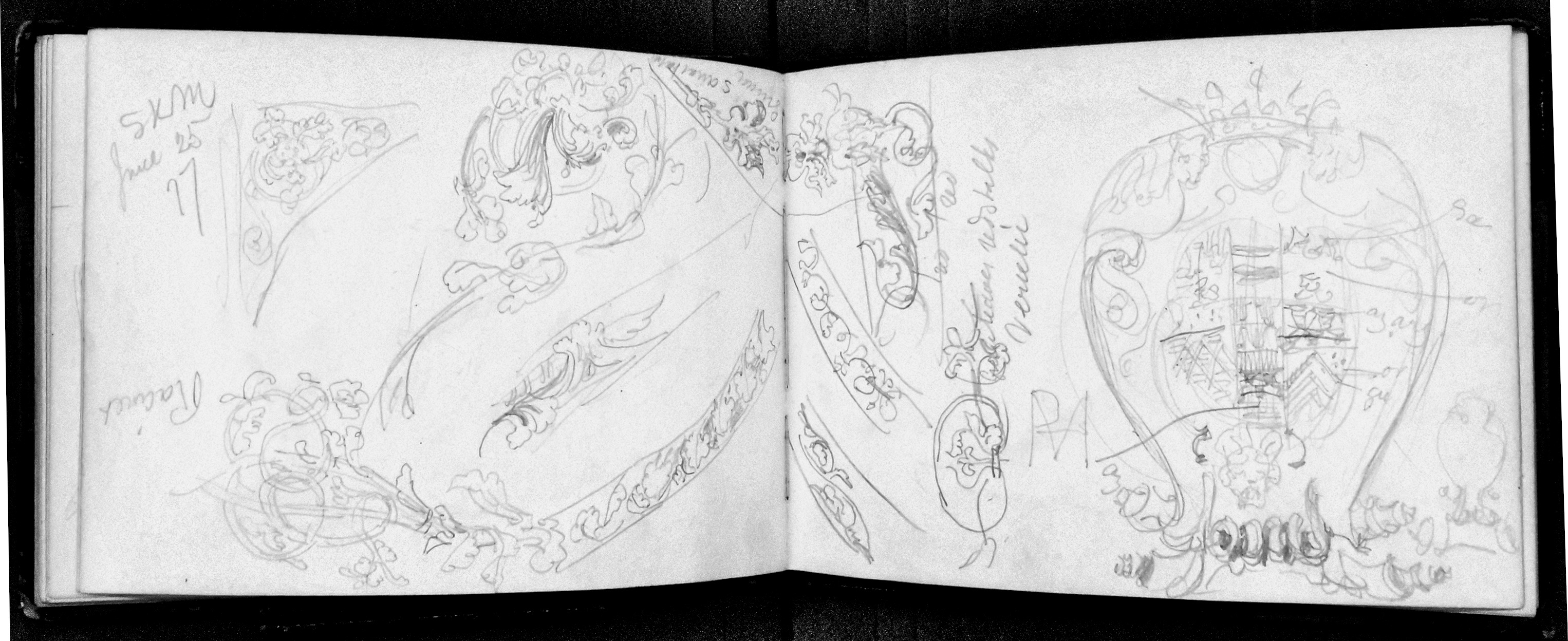

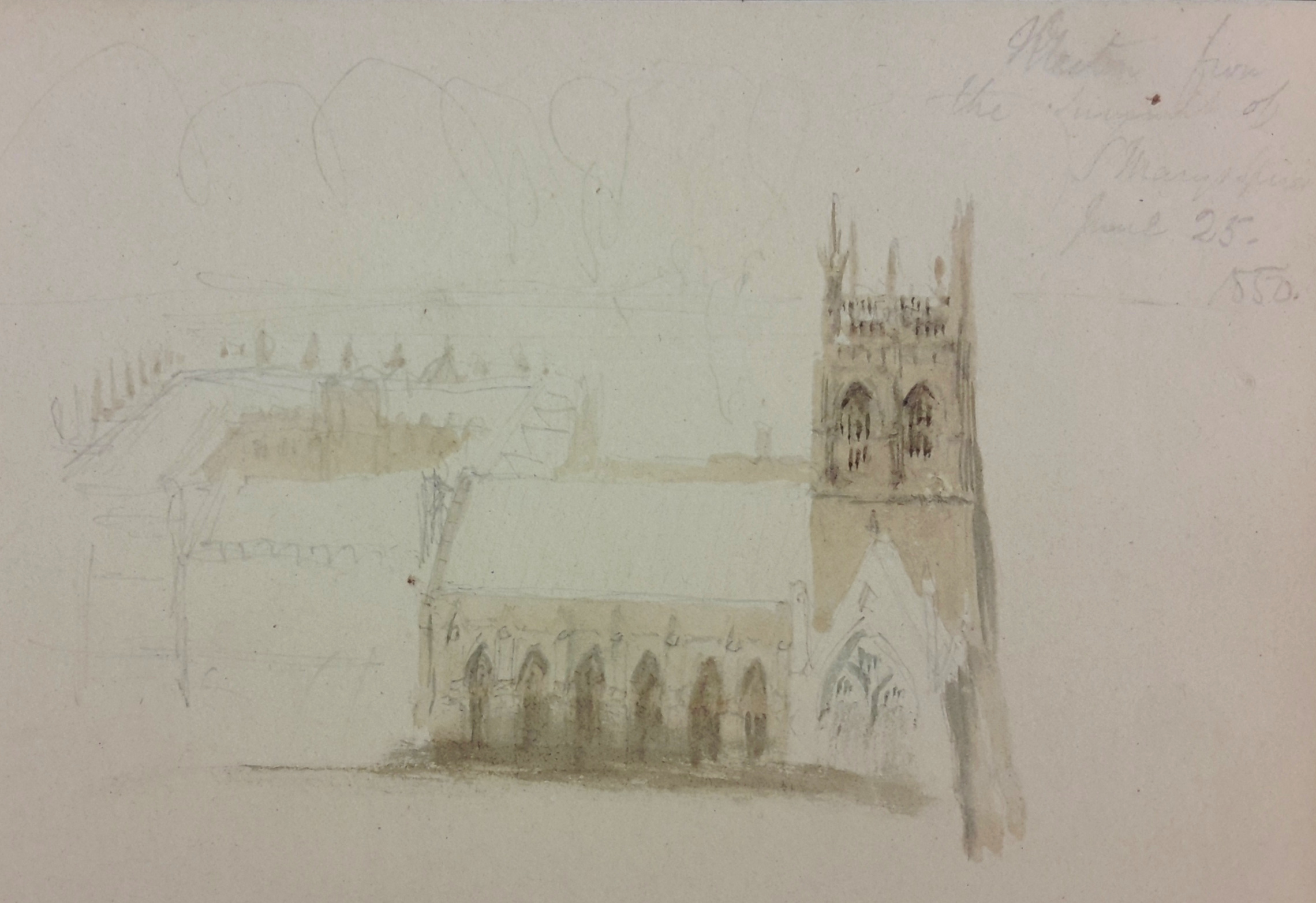

J.H. Pollen, sketches of Delhi, 17 November 1884 and of elephants, sketchbooks, Bodleian Libraries, Pollen archive, currently uncatalogued

J.H. Pollen, sketches of Delhi, 17 November 1884 and of elephants, sketchbooks, Bodleian Libraries, Pollen archive, currently uncatalogued

In 1902, Lord Ripon wrote of Pollen:

To me, he was a very dear friend, whose association with me had made me intimately acquainted with all the qualities of his admirable character; so gentle, and yet where matters of principle were concerned so firm… so perfect a gentleman and so good a man, that he won not only the sincerest respect, but the truest affection of all who knew him. (1)

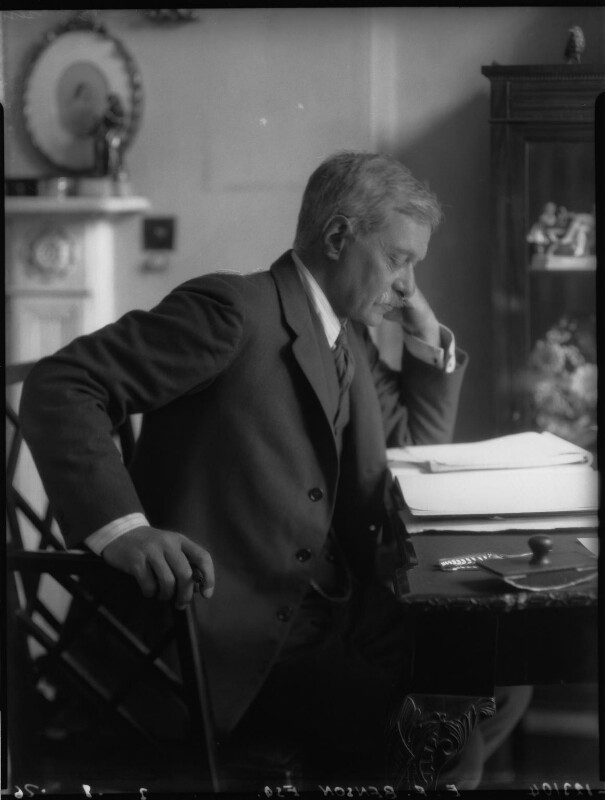

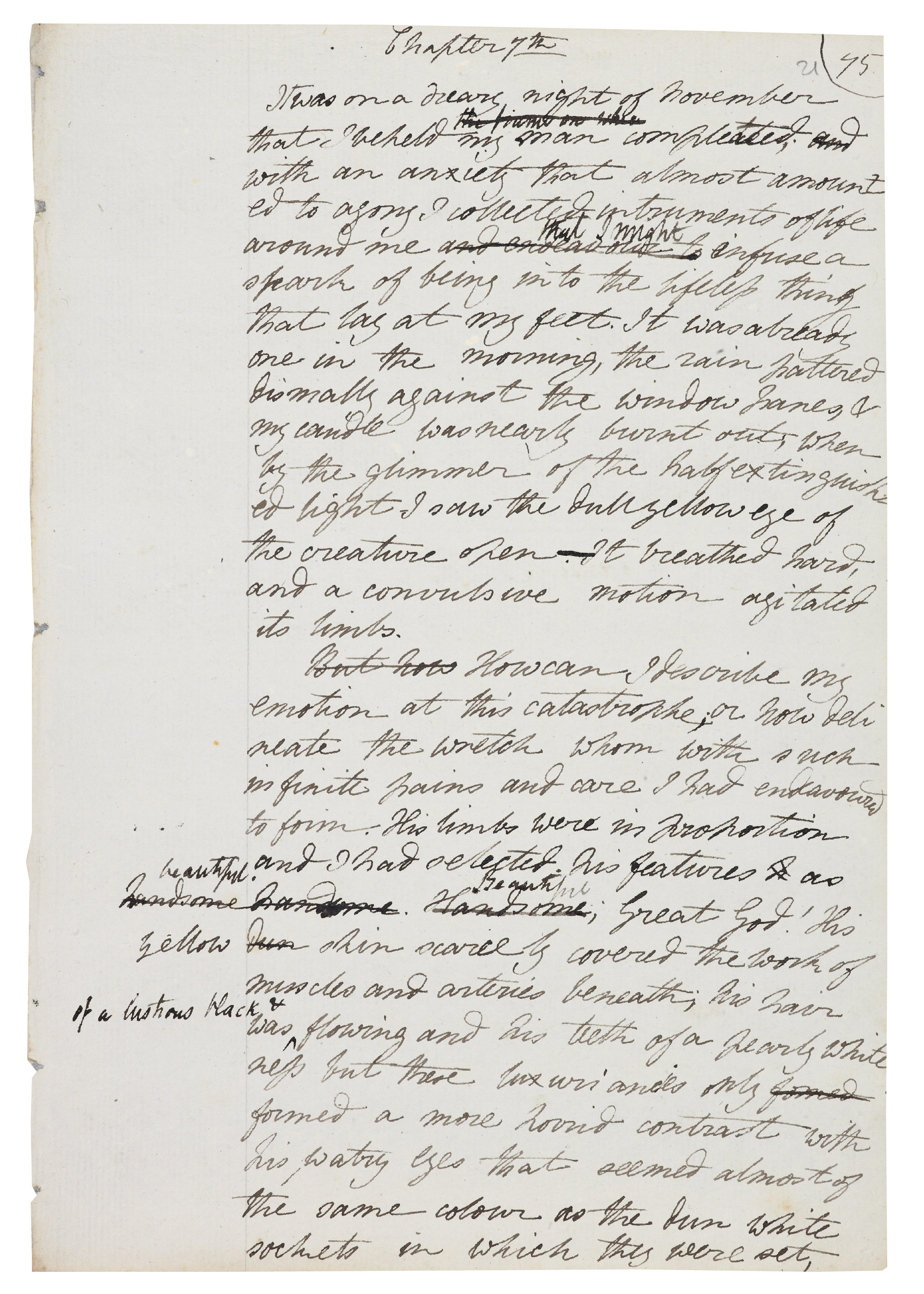

The poet and writer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840-1922) was a longstanding friend of Pollen’s wife’s family, the LaPrimaudayes, having first made their acquaintance as a child in Italy in 1852; after his marriage to Maria LaPrimaudaye, Pollen also became one of Blunt’s good friends. Anne, Blunt’s wife, was the daughter of William King, 1st Earl of Lovelace, and the Hon. Augusta Ada Byron (the pioneering mathematician now known more familiarly as Ada Lovelace). The Blunts owned Newbuildings Place in Sussex and in 1875 they leased it to the Pollen family who had by now expanded their brood to ten children.

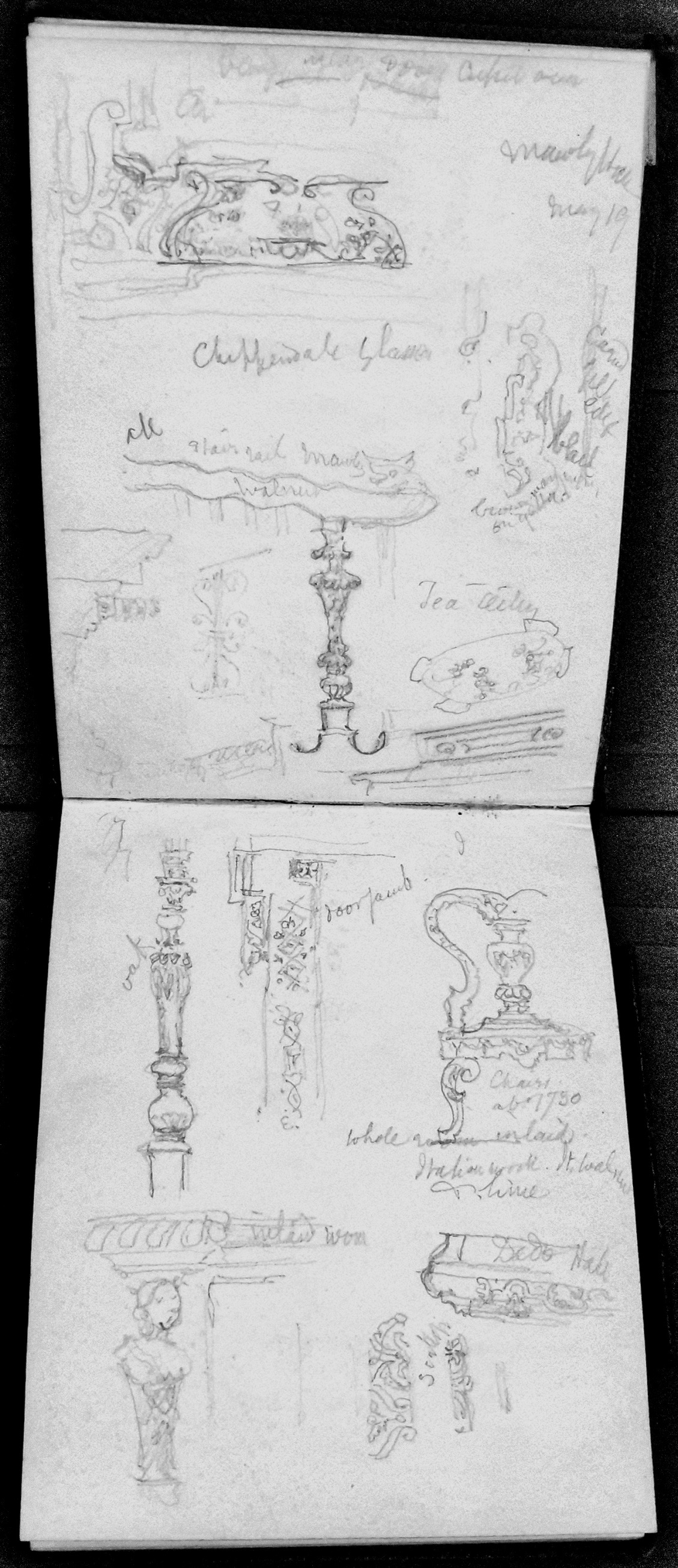

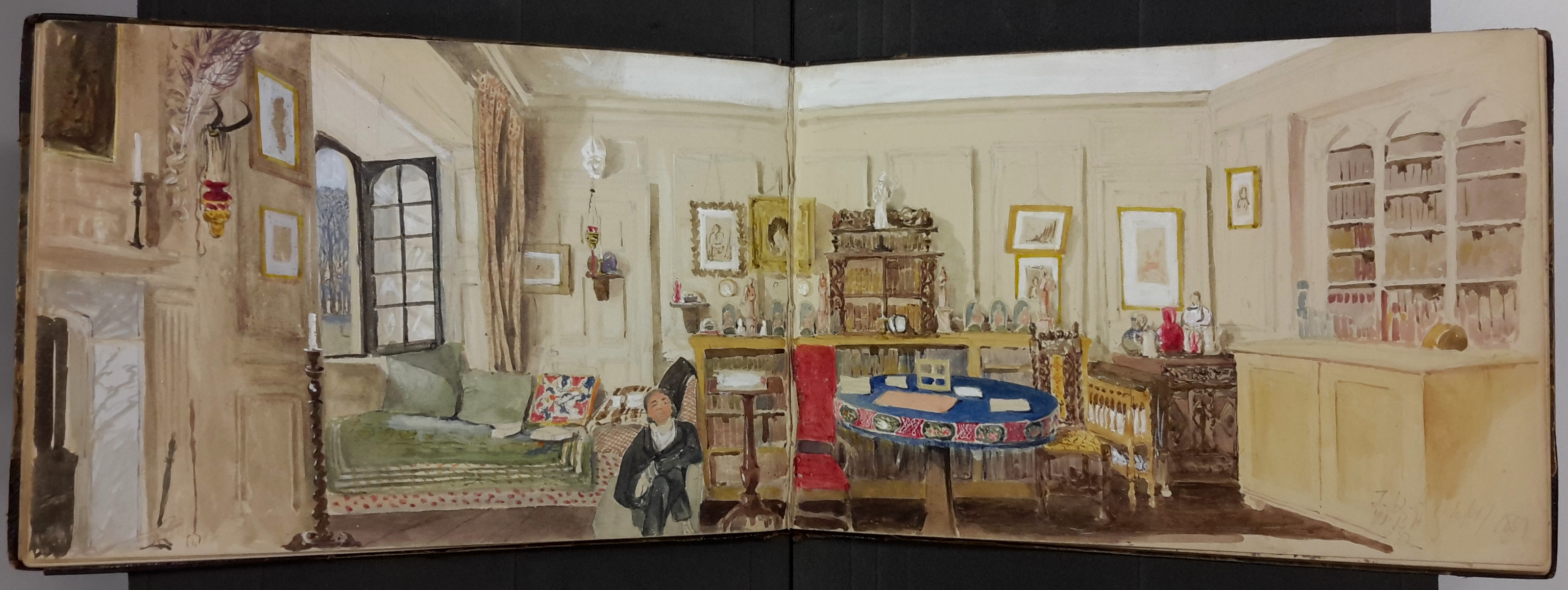

Sketch of Ashley Combe, Porlock, Somerset (house belonging to Ada Lovelace), 1851, sketchbook, Bodleian Libraries, Pollen archive, currently uncatalogued

Sketch of Ashley Combe, Porlock, Somerset (house belonging to Ada Lovelace), 1851, sketchbook, Bodleian Libraries, Pollen archive, currently uncatalogued

In 1886, Pollen became caught up with Blunt’s campaign for Home Rule in Ireland and when Blunt stood as a Liberal at Kidderminster, Pollen accompanied him during his election campaign (like Blunt’s other attempts to sit for Parliament, it was unsuccessful). Things were, however, to take a serious turn in October 1887 when Blunt chaired an anti-eviction meeting in Woodford in Galway which had been expressly banned by Arthur Balfour, the Irish chief secretary. Blunt was subsequently arrested and tried at Portumna, receiving a sentence of two month’s imprisonment with hard-labour. Pollen was there throughout the trial and Blunt would later remark that Pollen ‘was a very staunch friend to his friends’. (2)

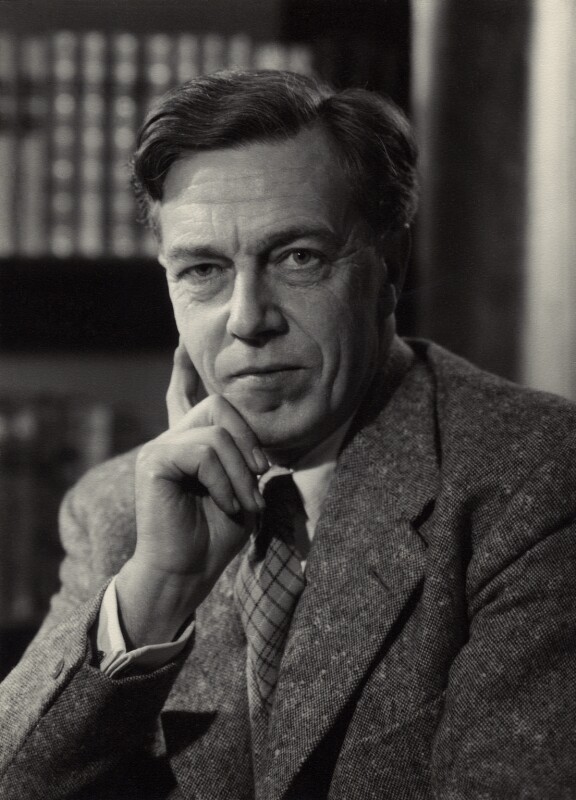

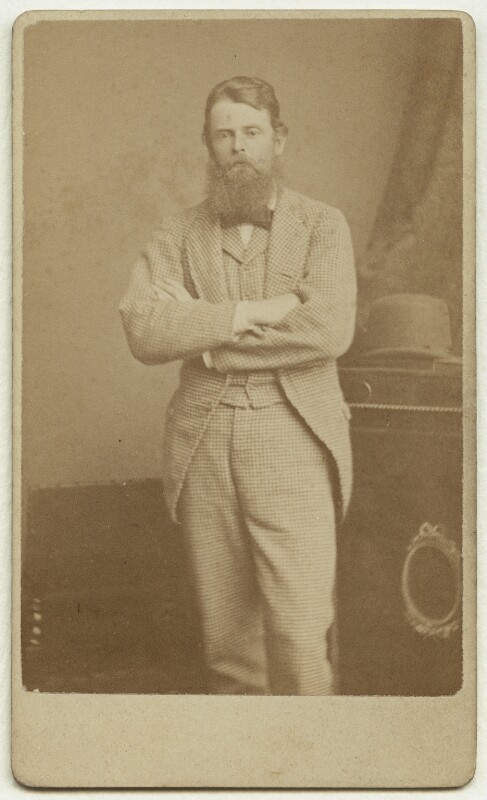

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt by Alexander Bassano, albumen carte-de-visite, circa 1870, NPG x1375 © National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt by Alexander Bassano, albumen carte-de-visite, circa 1870, NPG x1375 © National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The Pollens rented Newbuildings until 1889, when relations between the two families irretrievably broke down (Blunt’s daughter Judith had accused Pollen’s sixth son, Arthur Joseph Hungerford Pollen, of over-familiarity). Nevertheless, the friendship between Blunt and Pollen appears to have transcended even this disagreement.

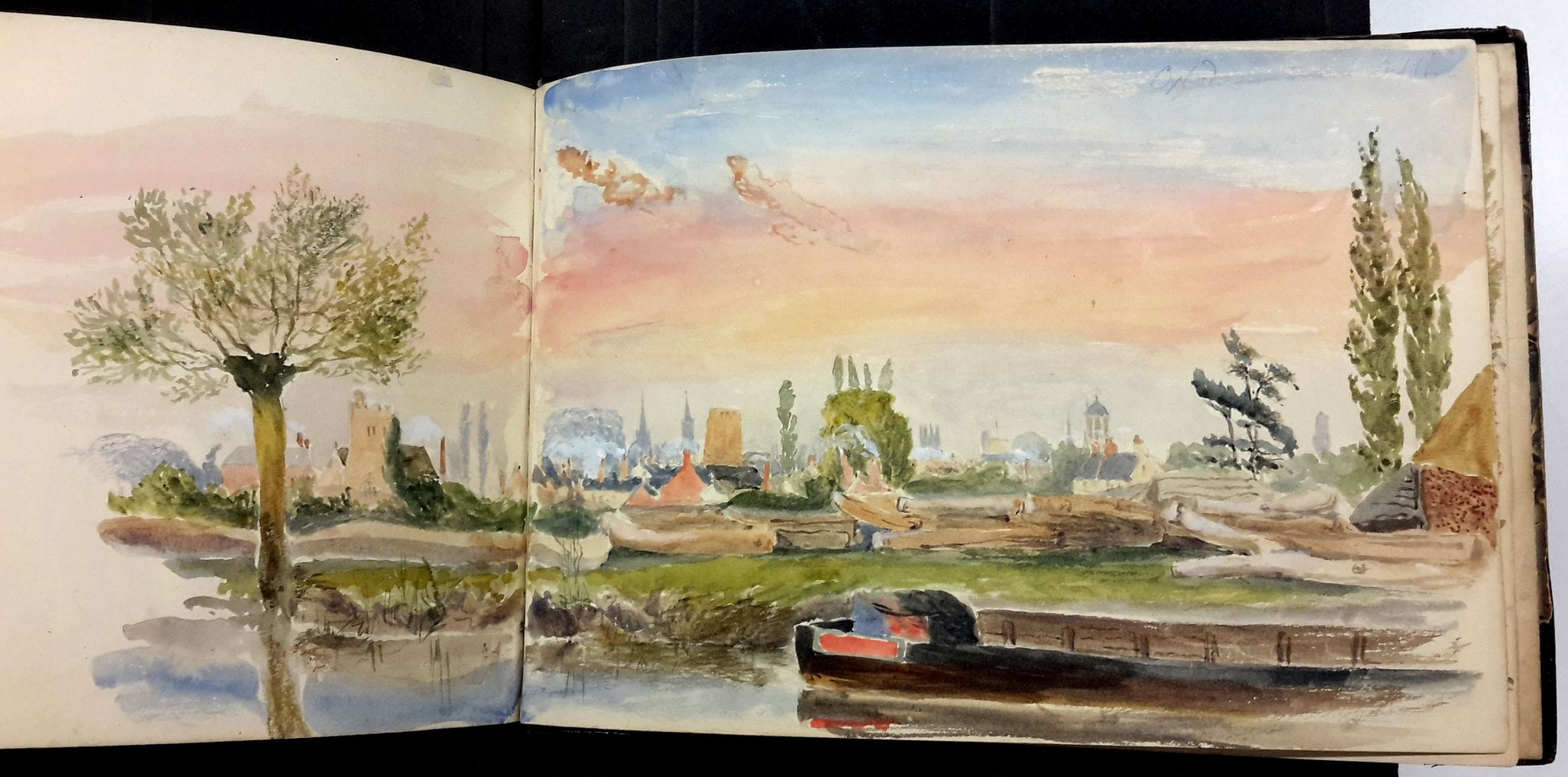

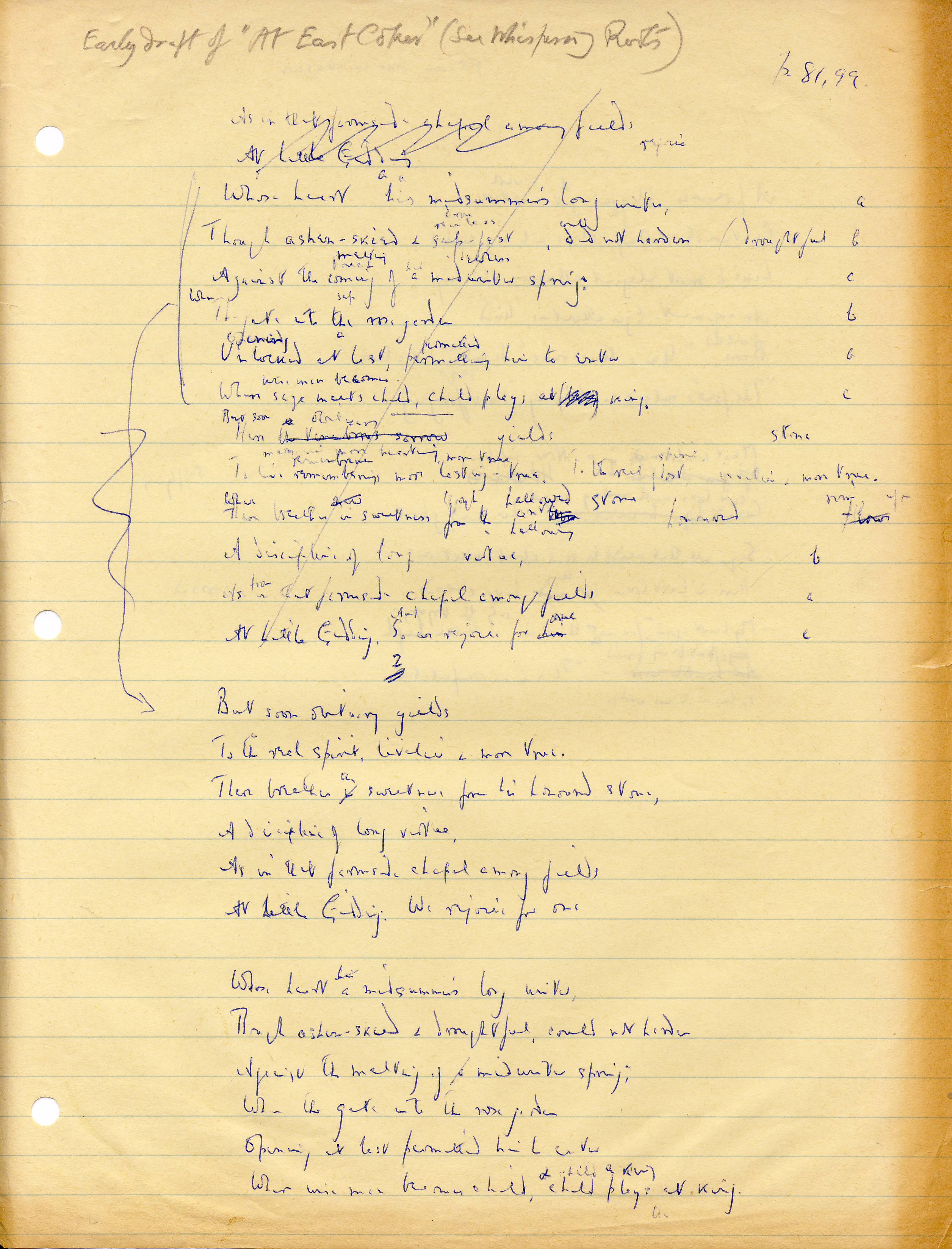

J.H. Pollen, sketch of Newbuildings, May 1882, sketchbook, Bodleian Libraries, Pollen archive, currently uncatalogued

J.H. Pollen, sketch of Newbuildings, May 1882, sketchbook, Bodleian Libraries, Pollen archive, currently uncatalogued

Tomorrow’s blog post is the last in this series and will focus on those closest to Pollen: his family.

-Rachael Marsay

References

1) Anne Pollen, John Hungerford Pollen, 1820-1902 (London, 1912), p.325.

2) Ibid, p.346.