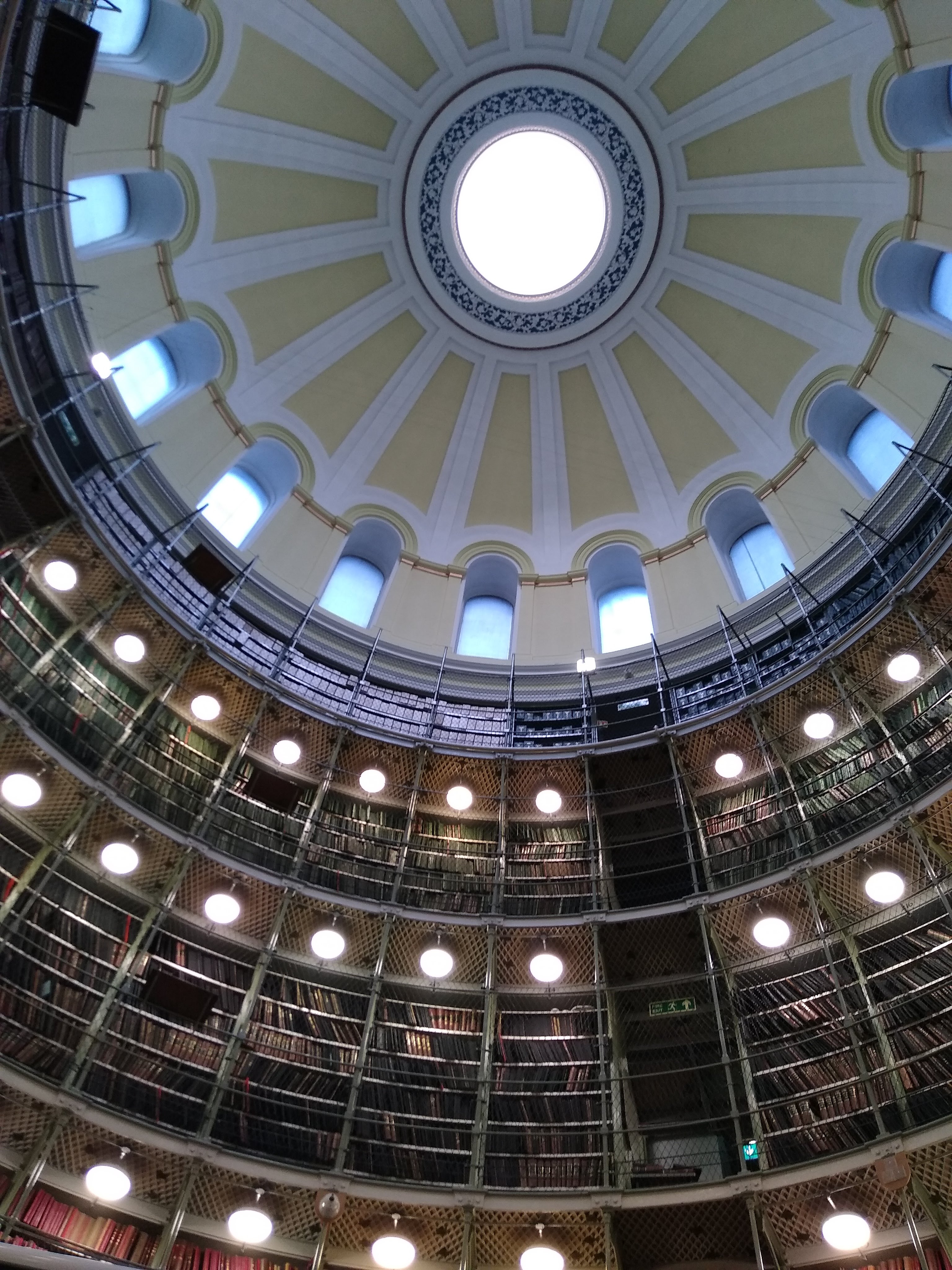

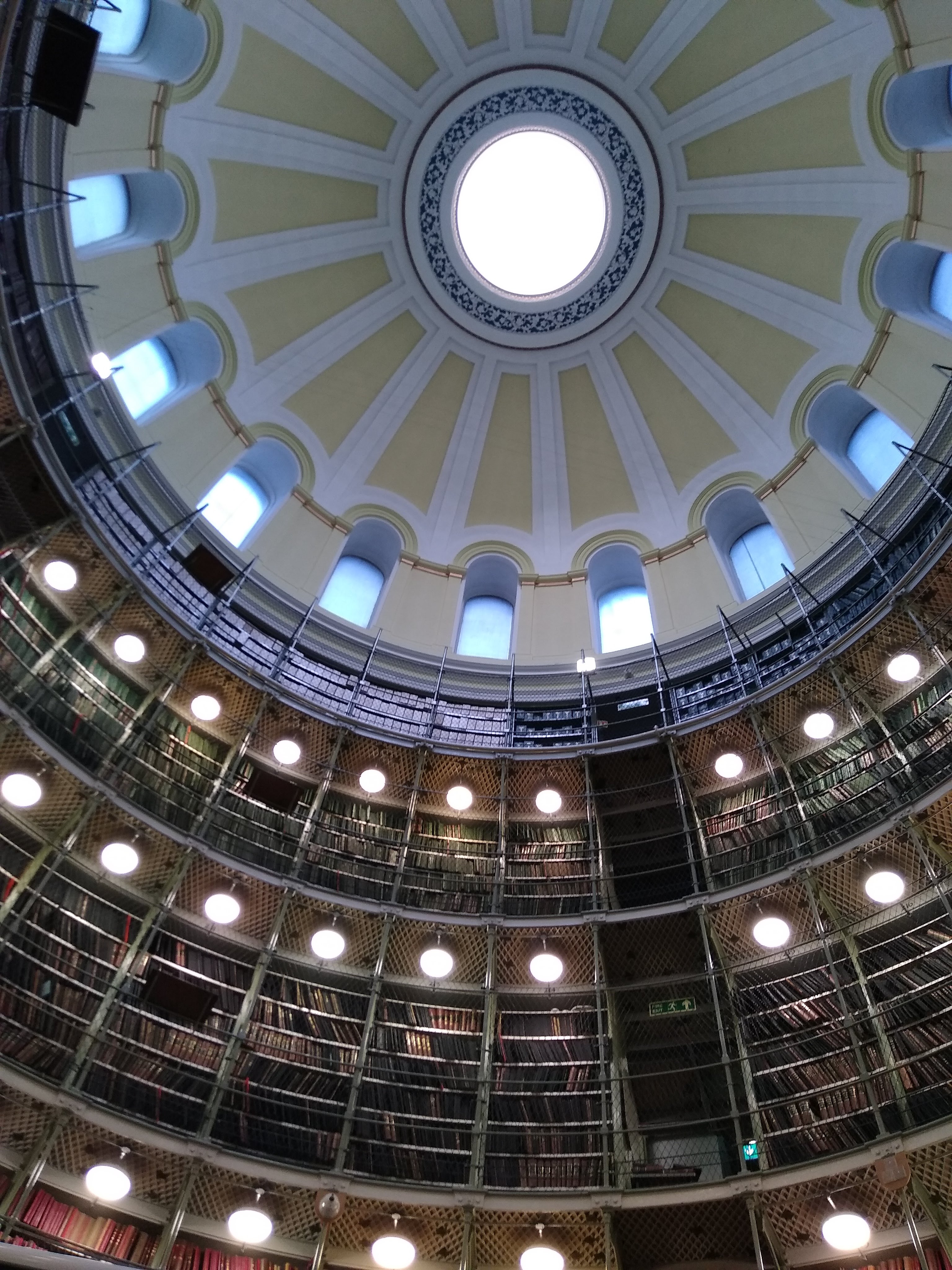

On January 16 2020, I had the pleasure of attending the first public meeting of the Digital Preservation Coalition’s Web Archiving and Preservation Working Group. The meeting was held in the beautiful New Records House in Edinburgh.

We were welcomed by Sara Day Thomson who in her opening talk gave us a very clear overview of the issues and questions we increasingly run into when archiving complex/ dynamic web or social media content. For example, how do we preserve apps like Pokémon Go that use a user’s location data or even personal information to individualize the experience? Or where do we draw the line in interactive social media conversations? After all, we cannot capture everything. But how do we even capture this information without infringing the rights of the original creators? These and more musings set the stage perfectly to the rest of the talks during the day.

Although I would love to include every talk held this day, as they were all very interesting, I will only highlight a couple of the presentations to give this blog some pretence at “brevity”.

The first talk I want to highlight was given by Giulia Rossi, Curator of Digital Publications at the British Library, on “Overview of Collecting Approach to Complex Publications”. Rossie introduced us to the emerging formats project; a two year project by the British Library. The project focusses on three types of content:

- Web-based interactive narratives where the user’s interaction with a browser based environment determines how the narrative evolves;

- Book as mobile apps (a.k.a. literary apps);

- Structured data.

Personally, I found Rossi’s discussion of the collection methods in particular very interesting. The team working on the emerging formats project does not just use heritage crawlers and other web harvesting tools, but also file transfers or direct downloads via access code and password. Most strikingly, in the event that only a partial capture can be made, they try to capture as much contextual information about the digital object as possible including blog posts, screen shots or videos of walkthroughs, so researchers will have a good idea of what the original content would have looked like.

The capture of contextual content and the inclusion of additional contextual metadata about web content is currently not standard practice. Many tools do not even allow for their inclusion. However, considering that many of the web harvesting tools experience issues when attempting to capture dynamic and complex content, this could offer an interesting work-around for most web archives. It is definitely an option that I myself would like to explore going forward.

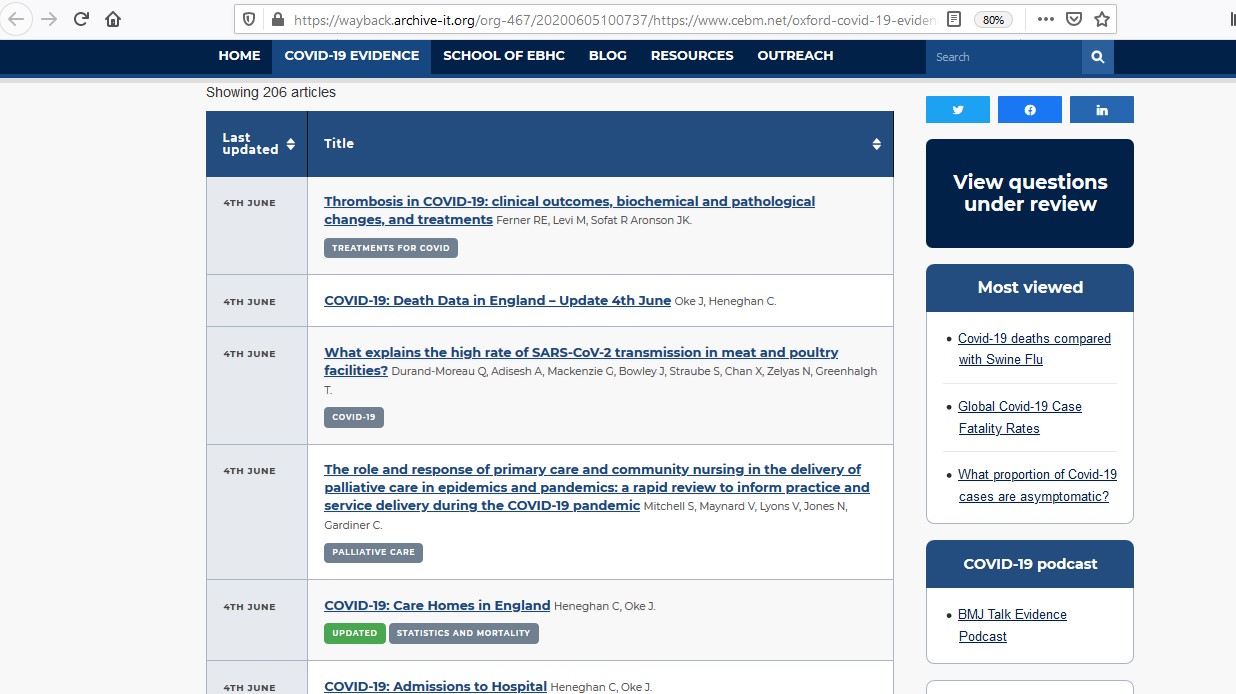

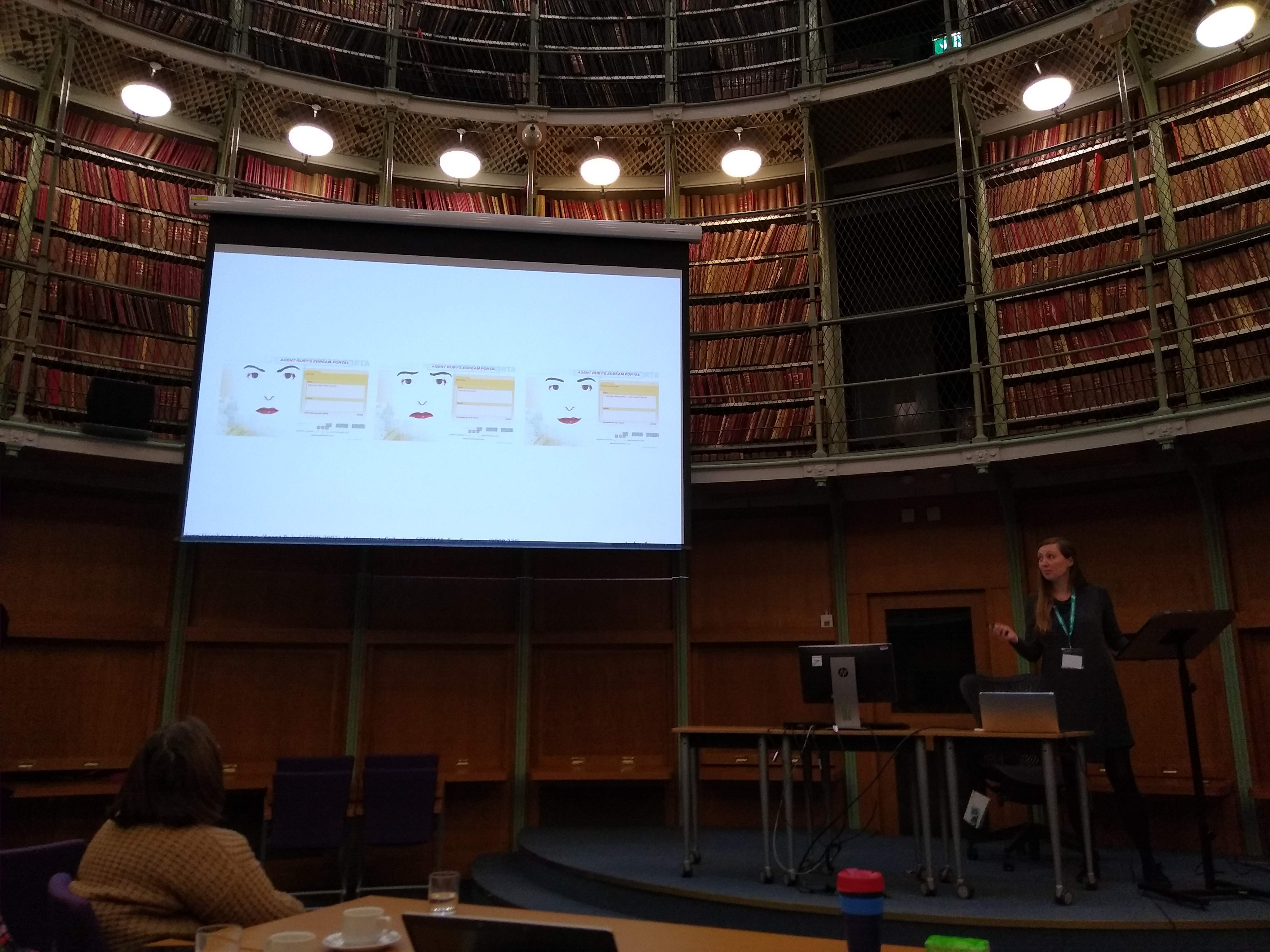

The second talk that I would like to zoom in on is “Collecting internet art” by Karin de Wild, digital fellow at the University of Leicester. Taking the Agent Ruby – a chatbot created by Lynn Hershman Leeson – as her example, de Wild explored questions on how we determine what aspects of internet art need to be preserved and what challenges this poses. In the case of Agent Ruby, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art initially exhibited the chatbot in a software installation within the museum, thereby taking the artwork out of its original context. They then proceeded to add it to their online Expedition e-space, which has since been taken offline. Only a print screen of the online art work is currently accessible through the SFMOMA website, as the museum prioritizes the preservation of the interface over the chat functionality.

This decision raises questions about the right ways to preserve online art. Does the interface indeed suffice or should we attempt to maintain the integrity of the artwork by saving the code as well? And if we do that, should we employ code restitution, which aims to preserve the original arts’ code, or a significant part of it, whilst adding restoration code to reanimate defunct code to full functionality? Or do we emulate the software as the University of Freiburg is currently exploring? How do we keep track of the provenance of the artwork whilst taking into account the different iterations that digital art works go through?

De Wild proposed to turn to linked data as a way to keep track of particularly the provenance of an artwork. Together with two other colleagues she has been working on a project called Rhizome in which they are creating a data model that will allow people to track the provenance of internet art.

Although this is not within the scope of the Rhizome project, it would be interesting to see how the finished data model would lend itself to keep track of changes in the look and feel of regular websites as well. Even though the layouts of websites have changed radically over the past number of years, these changes are usually not documented in metadata or data models, even though they can be as much of a reflection of social and cultural changes as the content of the website. Going forward it will be interesting to see how the changes in archiving online art works will influence the preservation of online content in general.

The final presentation I would like to draw attention to is “Twitter Data for Social Science Research” by Luke Sloan, deputy director of the Social Data Science Lab at the University of Cardiff. He provided us with a demo of COSMOS, an alternative to the twitter API, which is freely available to academic institutions and not-for-profit organisations.

COSMOS allows you to either target a particular twitter feed or enter a search term to obtain a 1% sample of the total worldwide twitter feed. The gathered data can be analysed within the system and is stored in JSON format. The information can subsequently be exported to a .CVS or Excel format.

Although the system is only able to capture new (or live) twitter data, it is possible to upload historical twitter data into the system if an archive has access to this.

Having given us an explanation on how COSMOS works, Sloan asked us to consider the potential risks that archiving and sharing twitter data could pose to the original creator. Should we not protect these creators by anonymizing their tweets to a certain extent? If so, what data should we keep? Do we only record the tweet ID and the location? Or would this already make it too easy to identify the creator?

The last part of Sloan’s presentation tied in really well with the discussion about the ethical approaches to archiving social media. During this discussion we were prompted to consider ways in which archives could archive twitter data, whilst being conscious of the potential risks to the original creators of the tweets. This definitely got me thinking about the way we currently archive some of the twitter accounts related to the Bodleian Libraries in our very own Bodleian Libraries Web Archive.

All in all, the DPC event definitely gave me more than enough food for thought about the ways in which the Bodleian Libraries and the wider community in general can improve the ways we capture (meta)data related to the online content that we archive and the ethical responsibilities that we have towards the creators of said content.