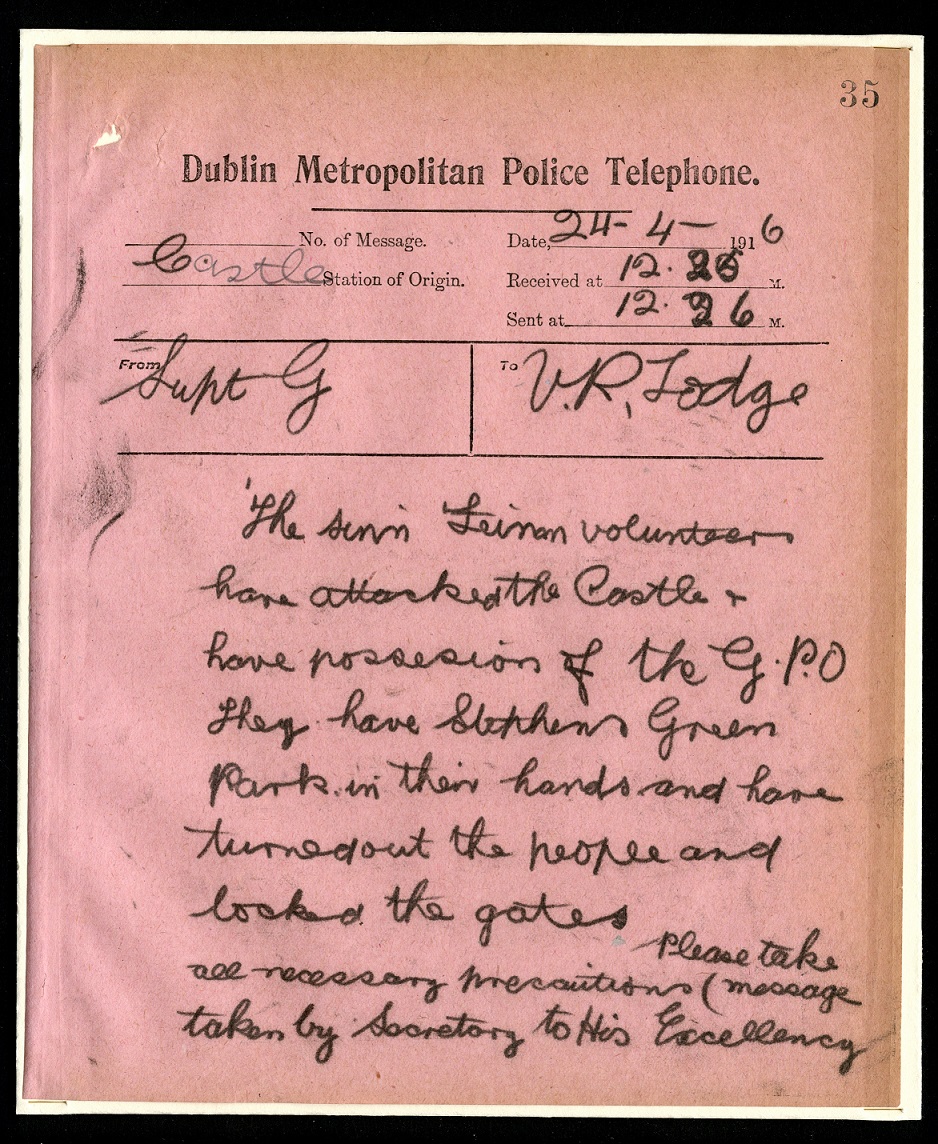

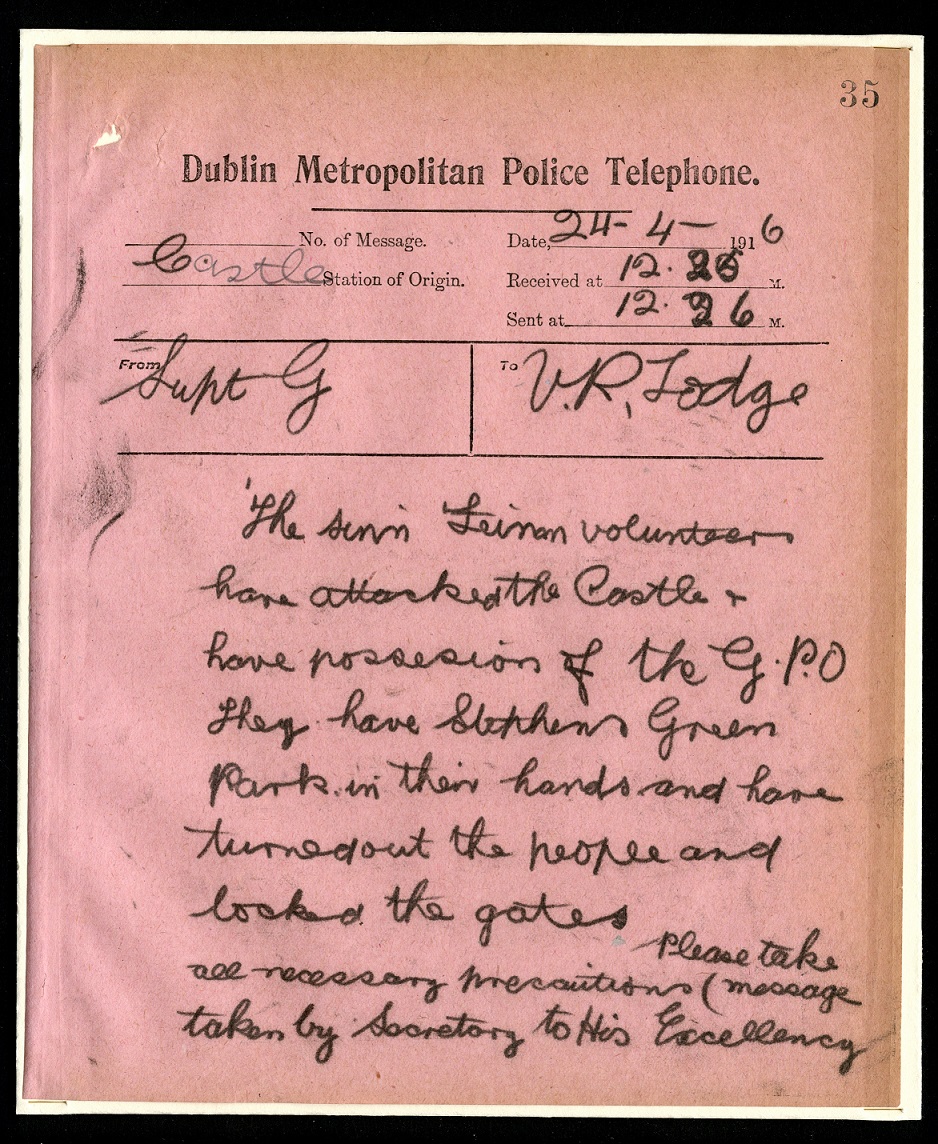

Dublin Metropolitan Police report, 24 April 1916 – MS. Nathan 476, fol. 35 – Click to enlarge

Guest post by Naomi O’Leary

The small pink slip is a snapshot of a world about to be upended. Jotted in cursive is a message from the Chief Superintendent of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, telephoned to all stations. It reports the movements of a suspicious vehicle, at that moment parked at the headquarters of Irish radical nationalist activity, Liberty Hall. The note is time-stamped 10:50am, the 24th of April, 1916. It is one of hundreds that will be published on social media this month, telling the story of the Easter Rising in real-time exactly one century on.

Outwardly, the streets of Dublin were quiet on that bank holiday Monday. But behind the doors of Liberty Hall, feverish preparations were underway. Men and women had gathered with rifles, rations, ammunition, and a stack of hastily-printed posters declaring an independent Irish republic.

Within days, British artillery guns would be raining shells on Dublin city. A chain of events was about to be set in motion that would presage the fall of the British Empire. The writer of the telephone note sat in Dublin Castle, the centre of British power in Ireland for centuries. She could not have imagined that within six years, the stronghold would be handed over to an Irish government, in a scene that would be repeated around the world in the coming decades as former colonies broke free.

The following telephone messages, each time-stamped to the minute, capture the cascade of events. At 11:20am: “Fifty volunteers have now travelled by tram car 167 going in direction of the city”. At 11:50, an anonymous report: “The volunteers are turning everyone out of St Stephen’s Green Park”. By 12:20, the world had changed. The Superintendent of the G Division, which tracked political crime, telephoned to the representative of the British Monarchy in Ireland, Lord Lieutenant Wimborne: “The Sinn Fein volunteers have attacked the Castle and have possession of the G.P.O.”

I came across these hundreds of telephone messages in the personal papers of Sir Matthew Nathan, who was the top civil servant in Dublin Castle that spring of 1916. Jotted down in the thick of events, sometimes in frantic handwriting, they such give a vivid account of the six day rebellion I felt my pulse beat faster.

Their brevity and immediacy reminded me of my own reporting of live events as a journalist, particularly of protests that threatened to spill out of control.

With the kind permission of the Bodleian Library and the help of volunteer transcribers, I have put together a project to mark the centenary of the rebellion by publishing each update on social media at the time it was logged, exactly one hundred years later. A short version of the updates will go out on Twitter from @1916live, while full documents will be published simultaneously at www.1916live.com.

The reason the documents survive as a collection is precisely because they give such a rich account of the rebellion. As the most senior figure in Dublin Castle, Nathan resigned after the revolt and was called to explain how it had happened to a Royal Commission of Inquiry in London. He gathered up his correspondence along with the telephone and telegraph records of Dublin Castle, and arranged them into chronological order into a collection that was later bound in leather. It was one among hundreds of boxes of his papers given to the Bodleian Library after his death. The documents in it span the course of the rising, concluding with the rebels’ surrender on April 29th.

This project will allow anyone in the world to experience this key moment in history as it unfolded through a unique primary resource. Publishing the telephone notes on Twitter seems particularly appropriate, as they are the records of a new system of technology from the time that allowed for real-time communication, which ultimately gave British authorities a key advantage in their response to the rebellion. The material will remain online afterwards as a freely accessible resource for the future.

For any questions or suggestions, please contact 1916live@gmail.com