A few months ago I applied for a scholarship through the DPC Leadership Programme to attend the DPTP 14-16 March course for those working in digital preservation: The Practice of Digital Preservation.

It was a three-day intermediate course for practitioners who wished to broaden their working knowledge and it covered a wide range of tools and information relating to digital preservation and how to apply them practically to their day-to-day work.

The course was hosted in one of the meeting rooms in the Senate House Library of the University of London, a massive Art Deco building in Bloomsbury (I know because I managed to get a bit lost between breaks!).

The course was three full days of workshops that mixed lectures with group exercises and the occasional break. Amazingly this is the last year they’re doing it as a three day course and they’re going to compress it all into a single day next time (though everything they covered was useful, I don’t know what you’d cut to shorten it—lunch maybe?).

Each day had a different theme.

The first was on approaches to digital preservation. This was an overview of various policy frameworks and standards. The most well-known and accepted being OAIS.

No Google, not OASIS!

Oasis, Oman. Taken by Hendrik Dacquin aka loufi and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

After a brief wrestle with Google’s ‘suggestions’ let’s look at this OAIS Model and admire its weirdly green toned but elegant workflow. If you click through to Wikimedia Commons it even has annotations for the acronyms.

After introducing us to various frameworks, the day mostly focused on the ingest and storage aspect of digital preservation. It covered the 3 main approaches (bit-level preservation, emulation and migration) in-depth and discussed the pros and cons of each.

There are many factors to consider when choosing a method and depending on what your main constraint is: money, time or expertise, different approaches will be more suitable for different organisations and collections. Bit-level preservation is the most basic thing you can do. You are mostly hoping that if you ingest the material exactly as it comes, some future archivist (perhaps with pots of money!) will come along and emulate or migrate it in a way that is far beyond what your poor cash strapped institution can handle.

Emulation is when you create or acquire an environment (not the original one that your digital object was created or housed in) to run your digital object in that attempts to recreate its original look and feel.

Migration which probably works best with contemporary or semi-contemporary objects is used to transfer the object into a format that is more future-proof than its current one. This is an option that needs to be considered in the context of the technical constraints and options available. But perhaps you’re not sure what technical constraints you need to consider? Fear not!

These technical constraints were covered in the second day! This day was on ingestion and it covered file formats, useful tools and several metadata schemas. I’ve probably exhausted you with my very thorough explanation of the first day’s content (also I’d like to leave a bit of mystery for you) so I will just say that there are a lot of file formats and what makes them appealing to the end user can often be the same thing that makes a digital preservationist (ME) tear her hair out.

Thus those interested in preserving digital content have had to develop (or beg and borrow!) a variety of tools to read, copy, preserve, capture metadata and what have you. They have also spent a lot of time thinking about (and disagreeing over) what to do with these materials and information. From these discussions have emerged various schemata to make these digital objects more…tractable and orderly (haha). They have various fun acronyms (METS, PREMIS, need I go on?) and each has its own proponents but I think everyone is in agreement that metadata is a good thing and XML is even better because it makes that metadata readable by your average human as well as your average computer! A very important thing when you’re wondering what the hell you ingested two months ago that was helpfully name bobsfile1.rtf or something equally descriptive.

The final day was on different strategies for tackling the preservation of more complex born-digital objects such as emails and databases (protip: it’s hard!) and providing access to said objects. This led to a roundup of different and interesting ways institutions are using digital content to engage readers.

There’s a lot of exciting work in this field, such as Stanford University’s ePADD Discovery:

Which allows you to explore the email archives of a collection in a user-friendly (albeit slow) interface. It also has links to the more traditional finding aids and catalogue records that you’d expect of an archive.

Or the Wellcome Library’s digital player developed by Digirati:

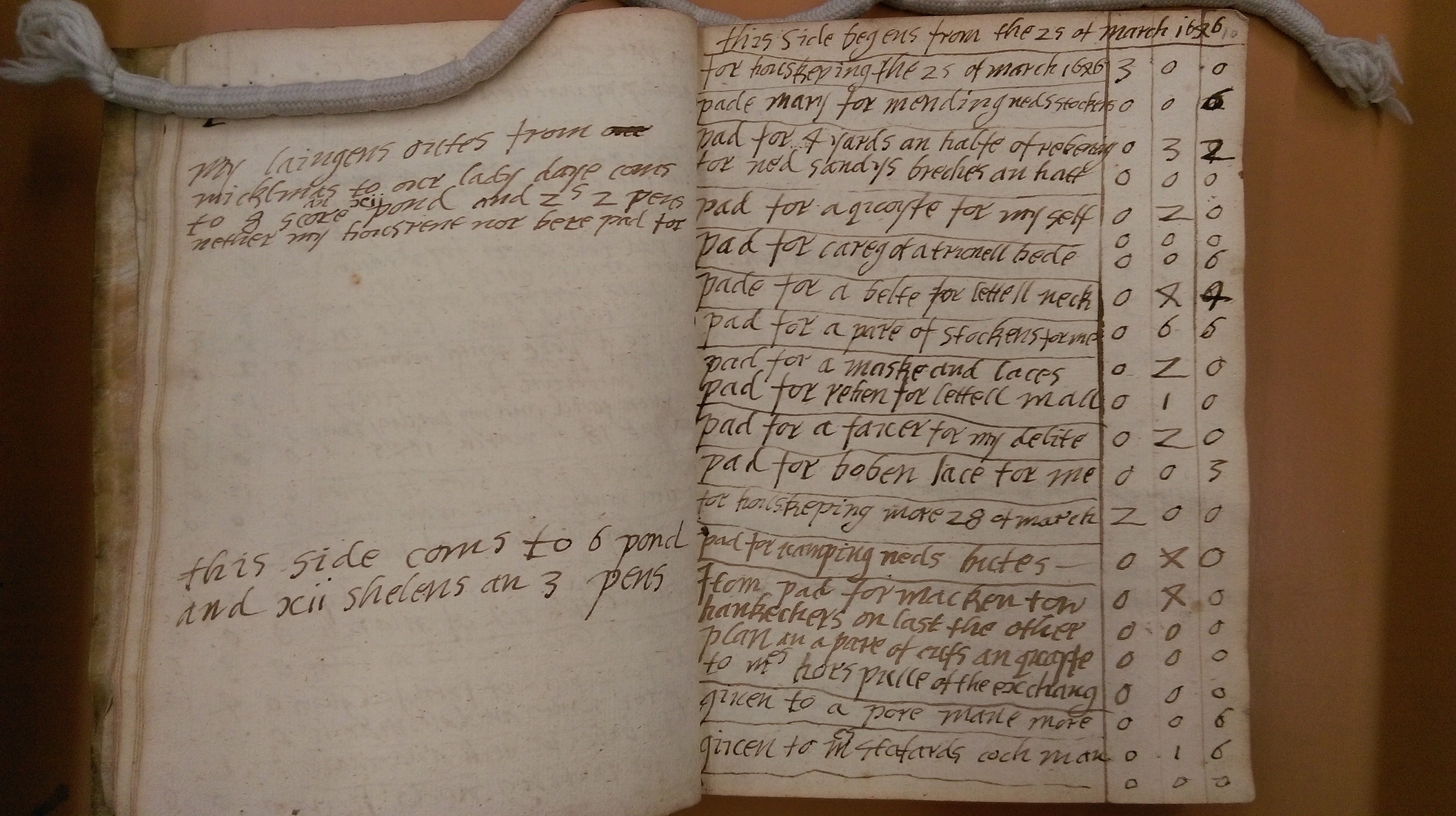

Which lets you view digital and digitised content in a single integrated system. This includes, cover-to-cover books, as pictured above, archives, artwork, videos, audio files and more!

Everyone should check it out, it’s pretty cool and freely available for others to use. There were many others that I haven’t covered but these really stood out.

It was an intense but interesting three days and I enjoyed sharing my experiences with the other archivists and research data managers who came to attend this workshop. I think it was a good mix of theory and practical knowledge and will certainly help me in the future. Also I have to say Ed Pinsent and Steph Taylor did a great job!