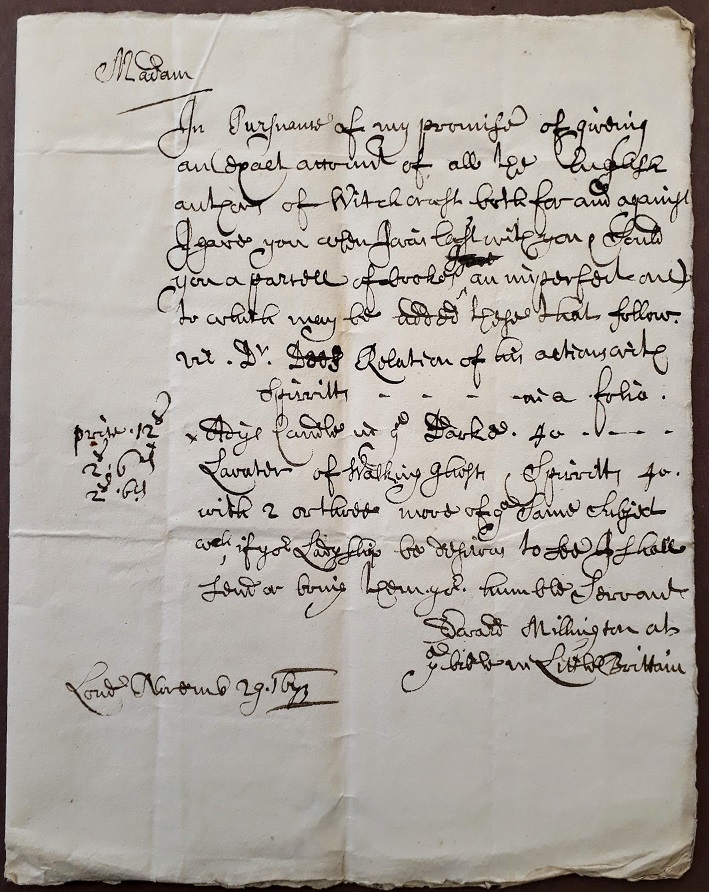

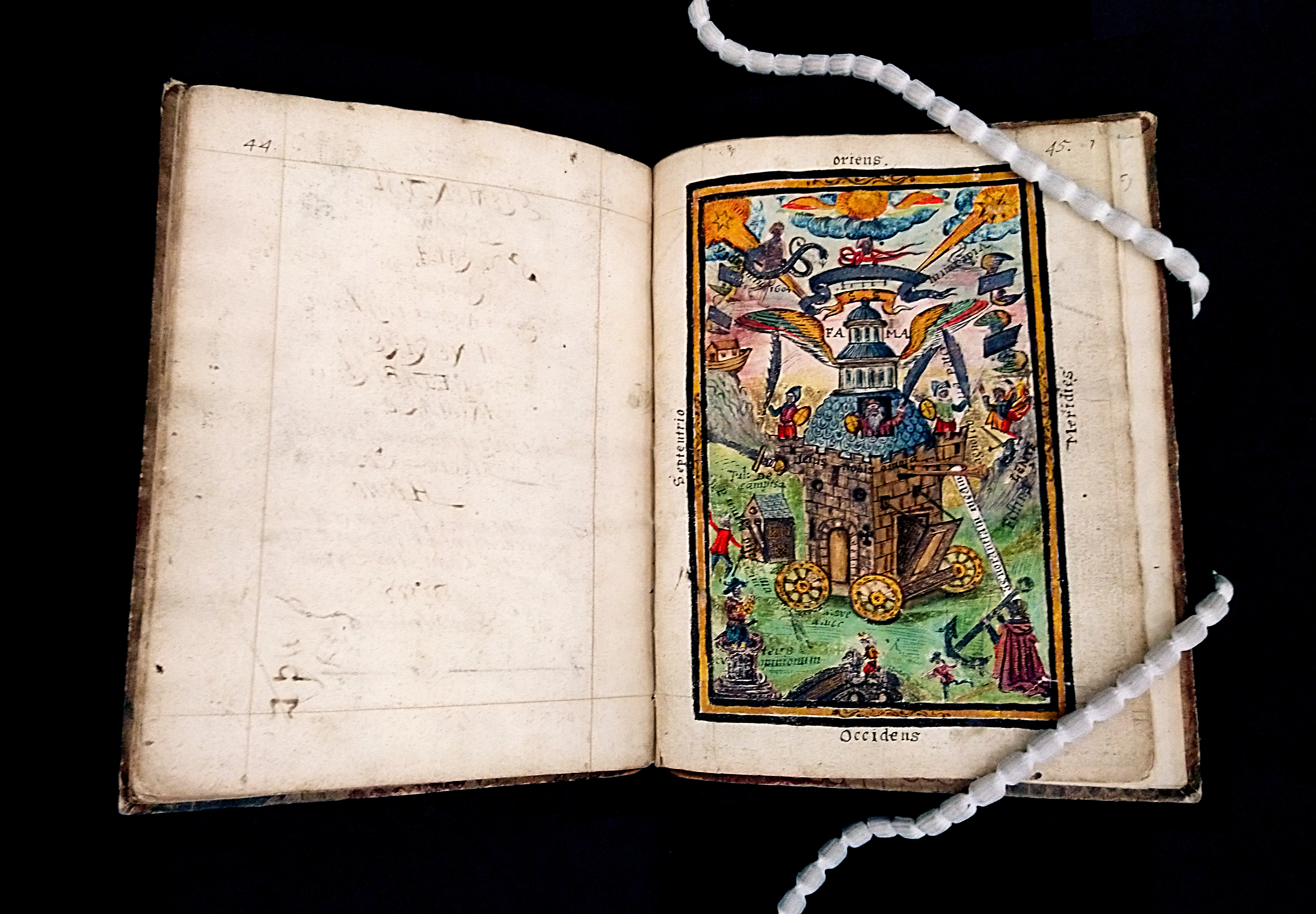

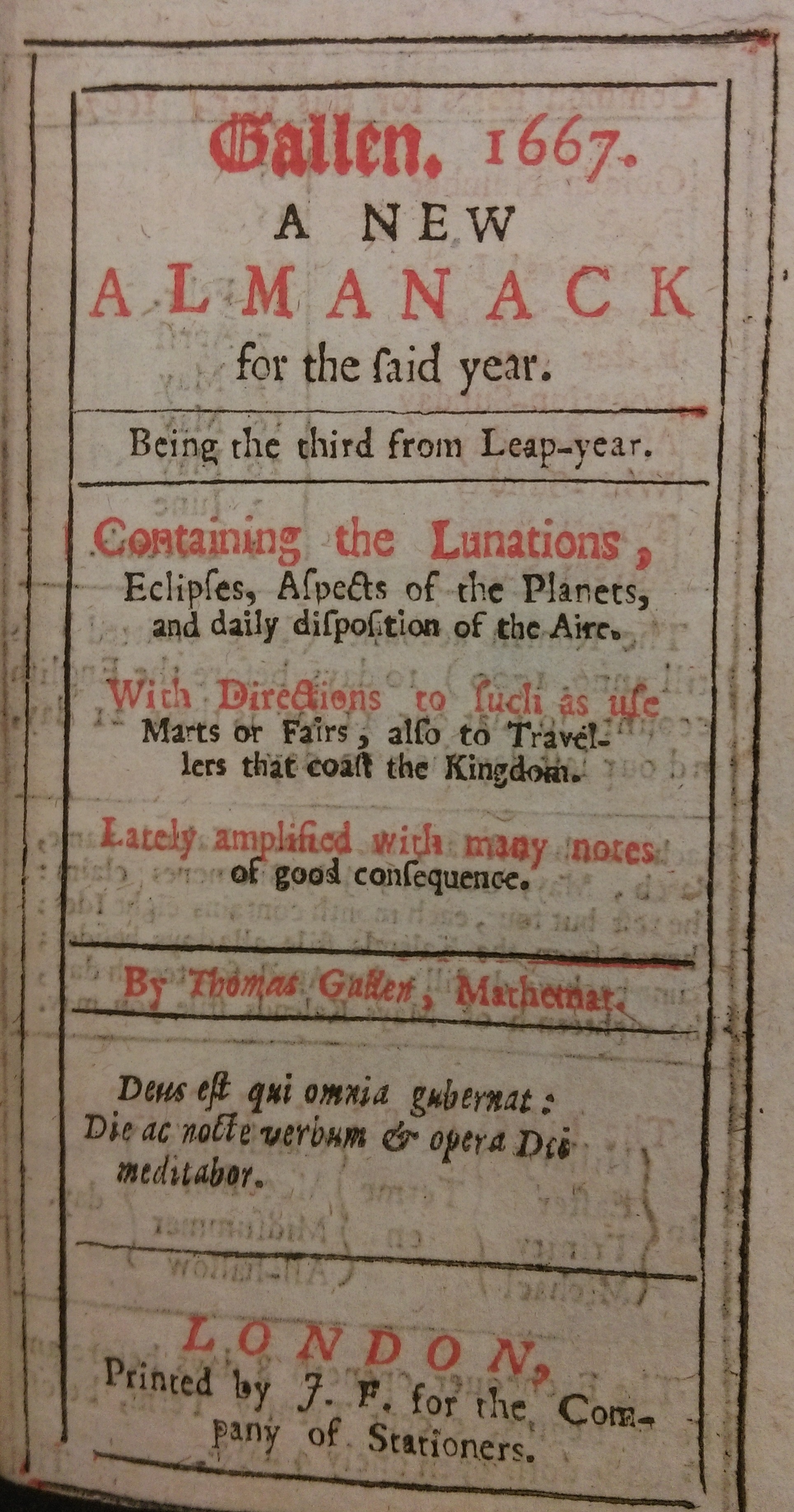

Warcup’s Gallen Almanack of 1672

The Rawlinson Almanacs

One of the joys of the Bodleian’s collections is that they are so rich and complex that there are still discoveries to be made, even among collections that have been here for 200 years or more. The sheer scale of the great and ongoing task of making the collections intelligible and available to researchers means that inevitably in attempting to cover broad areas, some individual items are missed.

Almanacs appear to be a case in point. While 17th-century almanacs can be found via SOLO, they are quite often only briefly described. But a number of them are unique items, containing manuscript memoranda, accounts and even diary entries. I have found an interesting late-17th century diary in the course of researching our collections of Gallen almanacs, as we have recently purchased a Gallen almanac of 1667 which contains a very interesting diary indeed – look out for news of this in the near future.

There are a number of almanacs in the Rawlinson collection, that vast and miscelleneous treasure house of books and manuscripts bequeathed by Richard Rawlinson in 1755. Many of these are in a separate sequence, shelmarked Rawl. Alm. Five almanacs bound together, including a 1672 Gallen almanac, have the shelfmark [Octavo] Rawl. 439. However, though SOLO does not record the fact, if these five little almanacs began life as printed books, they are no longer, because their owner kept his diary in them between 1670 and 1674.

Sir Edmund Warcup’s diaries unearthed

My attention was first drawn by the bold signature of one R. Warcup on one of the pages. Warcup was a name known to me. Sir Edmund Warcup (or Warcupp) was a lawyer and magistrate who makes it into the pages of the Dictionary of National Biography largely on account of his notoriety as an over-zealous pursuer of papists during the (mostly imaginary) Popish Plot of 1678. Subsequently he realigned himself with the Anglican-Tory interest in the aftermath of the Exclusion Crisis. Some of his papers relating to the interrogation of supposed plotters can be found in the manuscript collections in the Bodleian. His memorandum book on legal business 1652-1666 is in the Rawlinson collection (MS. Rawl. D. 930), and further miscellaneous papers are in MS. Rawl. D. 384. These papers, acquired as a result of Rawlinson’s bequest of 1755, were supplemented by further papers given to the Library by St. John’s College, Oxford, in 1953, comprising largely depositions taken before Warcup about the Popish and Presbyterian plots, 1678-82 (MS. Eng. hist. b. 204).

So my first thought on seeing the signature of R. Warcup was that this almanac might in some way be connected with Sir Edmund. A closer inspection revealed firstly, that the signatures (there are more than one) were in a different hand from the rest of the manuscript notes; secondly, a Robert Warcup is mentioned in the text as ‘brother’; and thirdly, the notes were partly a diary and partly memoranda, and the diary begins in January 1670 (New Style) with an account of rumours circulating at Court about the Queen’s wish to divorce Charles II and retire to Ham House. The diarist seems to have been active in spreading the gossip about, until one of his confidants went straight to the King and the diarist was told never to speak of the matter again!

Warcup diary January 1670 [New Style] – gossip about the Queen

Internal evidence suggested that the diarist might be Sir Edmund Warcup himself, particularly the several references to Northmoor, Oxfordshire, his country seat. The DNB article mentions a diary of 1676-1684, edited and published by K. G. Feiling and F. R. D. Needham in the

English Historical Review in 1925. Much to my surprise, this diary turned out to be in the Bodleian. The editors stated in their 1925 article that ‘certain journals of this Edmund Warcup, hitherto, it is believed, imprinted, have lately been discovered in the Bodleian Library’. They are in fact among the Rawlinson Almanac collection and have the shelfmarks Rawl. Alm. 201-203, though I have found no trace of a catalogue of these discoveries either in SOLO or in the Printed Books with MS Additions catalogue. There are two volumes of a diary 1676-1684, and a further volume comprising little more than brief memoranda 1708-11. So although these diaries were discovered in 1925, and the edition by Feiling and Needham has been cited by scholars of Restoration history ever since, the original diaries have remained as nothing more than printed almanacs in our own catalogues. And the annotated almanacs I have discovered take Warcup’s diary back to 1670. Feiling and Needham missed it for one simple reason – it is not in the Rawlinson almanac series. The 1670-1674 diary was for some reason now unfathomable, given the shelfmark [Octavo] Rawl 439. Presumably at some early stage in its life, it became separated from the others.

Three volumes of Warcup’s diary. The two to the right unearthed in 1925, the one on the left in 2016. Acquired 1755.

Feiling and Needham’s edition provided all the remaining evidence needed to be sure it was Sir Edmund’s diary I was looking at. The introduction in the EHR article mentions that Warcup, after a spell out of favour occasioned by his over-free use of Arlington’s name ‘to cover some financial transactions of his own … resumed in 1667 a long career as farmer of the excise for Wiltshire and Dorset, again became a justice, and added a commissionership in wine licences.’ Part of the newly discovered diary is indeed a ‘Journall into the West in anno 1673 about the wyne lycences’; and Arlington is mentioned very early in the diary when Warcup notes that on 3 January 1670 ‘Lady Arl[ington] presented M. to Q. who kissed her hande’. Q. is clearly the Queen, and M. is harder to fathom, but might be the Duke of Monmouth (see below).

Any remaining doubts about authorship were dispelled as soon as I compared the diary with the ones discovered in 1925. The binding, handwriting and even historic damp damage were alike in all the volumes. There were even memoranda cross-referenced from the ‘new’ volume to the others.

Entry from Warcup’s 1679 diary in Rawl. Alm. 201. Warcup is exasperated at the scepticism shown towards evidence of a Popish Plot offered by the notorious Titus Oates whom Warcup was all too ready to believe.

Warcup’s later diaries have long been established, thanks to Feiling and Needham’s extracts, as a major source for proceedings in the Popish Plot. Although the recently discovered diary covers a perhaps less interesting phase of Warcup’s career, it is nevertheless a valuable document. It contains a mixture of London and Oxfordshire entries. Warcup’s career began in London where he was he was a JP, and he had connections with Shaftesbury, the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The London sections include much court gossip and records meetings with courtiers. For example, in November 1670 Warcup describes an encounter with the Duke of Monmouth and the Prince or Orange:

“At the Dukes Play house. D.M. led An to her coach. We were at Lincolnes Inn Revels. M. there spoke to us, & at 7 next morne, Prince of Orange, Mon. & Ld Rochester came & danced & caused Pitts & his son fidlers to play before our doore, and threatned to fire Pitts his house.

Sunday night at Court, and well receved by all the Court from high to low. Abt 2 of the clocke came the same company without musicke. Mon. drove the coach; all swore rashly. Mon. prest them to silence, becaus where they were. I feare some outrageouse act.”

As already mentioned, there is a 1673 West Country diary which describes the process of selling rights to trade in wine to various merchants in Bath, Bristol and other West Country towns. Otherwise, much of the diary is taken up with Oxfordshire matters.

Warcup and Northmoor

The memorial to Sir Edmund Warcup, who died in 1712, is in the church at Northmoor, Oxfordshire. I made a visit on Boxing Day intending to take a photograph of his monument for this blog post, but unfortunately the parish has not managed to resist the temptation to use Warcup’s rather fine monument as a table, and I found it piled high with kneelers, parish newsletters and other bits and pieces. It seems that Edmund Warcup has not only been neglected by the Bodleian! I carefully moved a large and heavy folding table leaning up against one side to take a picture of the rich stonework.

Side of Sir Edmund Warcup’s memorial, Northmoor church

The church has other very interesting remains from the late Stuart period, including a west gallery said by Pevsner to have been erected in the 1690s. At one end is a 1701 inscription bearing the name of Richard Lydall, with a wonderful verse carved into it:

‘Richard Lydall gave a new bell/ And built this bell loft free/ And then he said before he dyed/ Let ringers pray for me/ 1701’

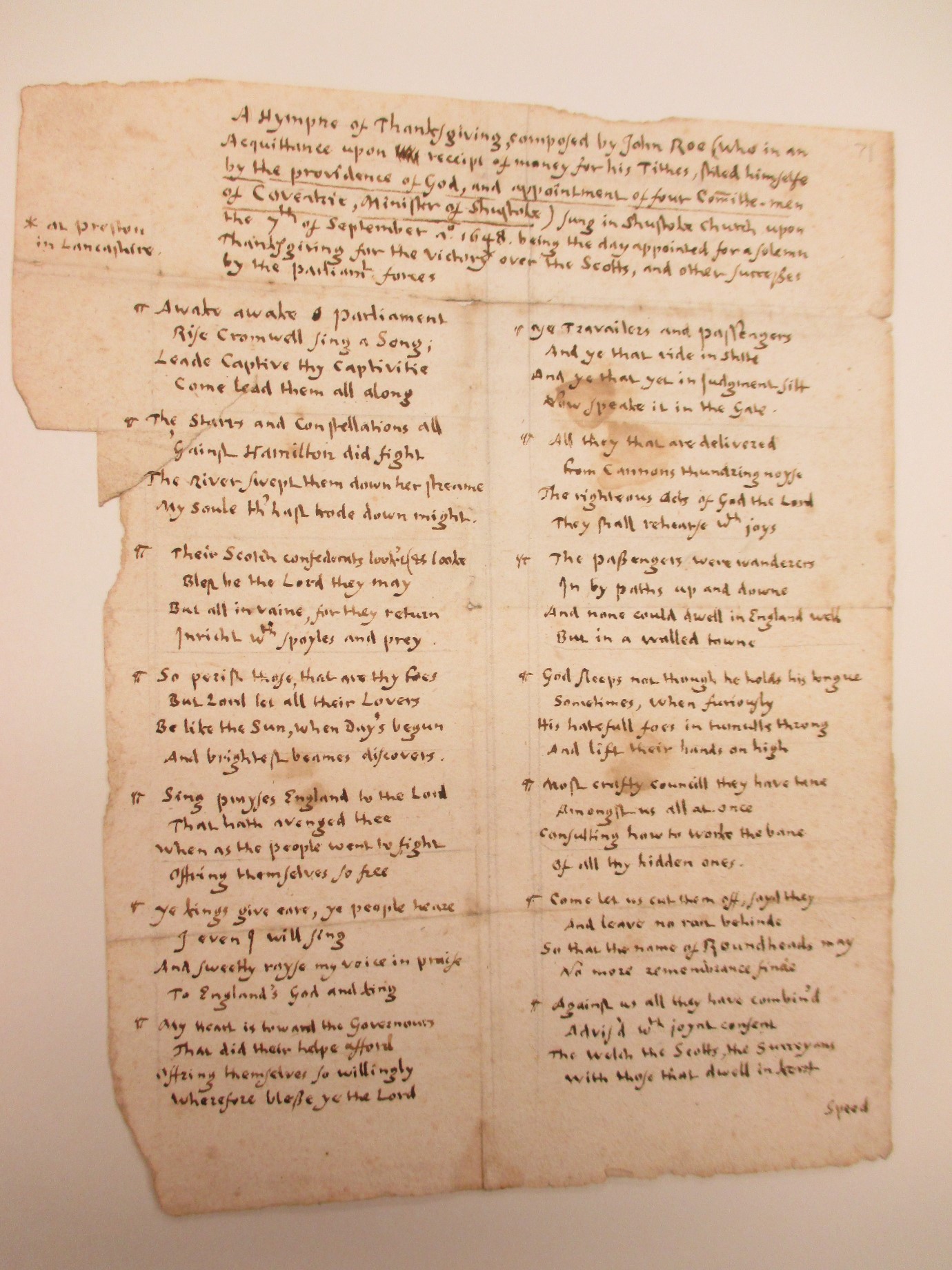

‘Rude, undecent & violent’ disputes

The charming rural idyll that this may conjure up is destroyed when one discovers the nature of the relationship between Lydall and Warcup. Richard Lydall appears in Warcup’s diary in rather contentious circumstances. There are two memoranda dated March 1672 [New Style], and signed by E. Warcup, R.W. (his brother Robert) and others. The first states that Richard Lydall before witnesses ‘declared he never saw the circle libell but in Mr Henry Martins hands, & that he (HM) only shewed it to him (RL)’. There follows a rather cryptic statement from Lydall that

“he & Mr Martin were at Westchester the last Whitsuntide when Mrs Martins mounds & the colledges were pulled up”.

The second memorandum provides more enigmatic clues about this incident. Now Lydall admits that the wrtiting of the superscription on this ‘circle libell’ was very like his own, and

“that he beleived there were 40 foote and 20 horse out at Whitsuntide last when the mounds were pulled up, that he was out with a brome in his hand that night, that hee sawe the 2 libells with the prints of gates over them in the hands of Wm Bedford, Wm Bedwell, & at the parsonage”.

Worse still, the libel was shown to many persons, and Mrs Martin’s maid, among others, had read it.

This obscure reference must surely relate to a dispute between various Northmoor farmers and Warcup about enclosure of common land in the parish. A decree in Chancery, 1672 (C78/1264, very fortunately scanned and published on a website hosted by the University of Houston) outlines the whole case, and names the people mentioned in the memoranda in Warcup’s diary. ‘Mrs Martins mounds and the colledges’ must refer to some kind of boundaries that might have been destroyed in protest about the enclosure. The Chancery decree which was drawn up just a few months after the incident, certainly enjoins the parties to erect new mounds and fences:

“all the new mounds & fences to bee made betwixt party & party from Gaunt house & Stanlake Broad to Babliocke hythe as alsoe from master Hewes his plott adjoyning to West Mead & soe downe to Northhurst … shall bee ditched & throwne up…”

The ‘college mounds’ must have belonged to St John’s College, Oxford, landowners in the parish and one of the parties to the decree. It would appear that Warcup was enclosing fields and ran into dispute with his neighbours, and that the libel somehow related to that. The decree is extemely lengthy and lays out the rights and obligations of all parties in the formation and use of the enclosed lands. According to A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 13, Bampton Hundred (Part One), Warcup acquired Northmoor manor in 1671. His diary for 1671-1672 is almost entirely taken up with aspects of the Northmoor enclosure, with notes of meetings and accounts of expenditure. The memoranda about the ‘circle libell’ appear at the end of this sequence. On 5 March 1672 Warcup had noted in the diary that William Bedford admitted having seen the ’round libell’.

Warcup’s feud with Lydall continued beyond 1672. In MS. Rawlinson D. 384, fols. 44ff we find a copy of a suit of Richard Lydall and Frances Fairebeard, widow, both of Northmoor, against Edmund Warcup, concerning his exclusive right to seats in the aisle of Northmoor church, heard in the church courts in Oxford. The document runs to nearly fifty pages and includes sworn depositions of many Northmoor parishioners, a number of whom appear in the Chancery decree mentioned above, and in the memoranda about the ‘circle libell’. The case reveals that there was no love lost between Warcup and Lydall. It seems that Warcup’s right to the pew had been established by an earlier ruling, but Lydall resented the pretensions of this newcomer to the parish. The court document states that

“there was a doore or doores with a locke or lockes & wainscott partition or some other fence erected & sett up to secure the use & right of the said isle to him the said Edm. Warcupp & his family”

Lydall was charged that he, or others appointed by him

“didst on or about the thirteenth day of November last past [1677] (being a day appointed by his most sacred Majesty for a publick fast) breake downe the doore with lock partition or fence of the said isle in a rude undecent & violent manner contrary to the order & decree of thy lawfull Ordinary [the Bishop’s representative in the Church court].”

Furthermore,

“after the said breaches and defects were repaired & mended at the proper costs & charges of Edm. Warcupp .. you the said Rich. Lydall not being content with thy misdemeanours … (but persisting therein & adding thereunto) didst on or about the 17 day of November last past (being a Sunday) againe breake downe the aforesaid fence & doore … & after that thou or some other by thy direction … didst alsoe place two stooles or other seates in the said isle & didst thereupon seate thy selfe & wife or some other on thy part & behalfe, to the great disturbance of the said Edm. Warcupp Esqr his Lady & family …”

MS. Rawl. D. 384, fols. 44ff – Lydall attacks Warcup’s pew

Have you seen this manuscript?

I am clearly not the first person to have seen Warcup’s diary in [octavo] Rawl. 439, but the lack of any record of it in either our printed book or our manuscript catalogues suggests that I am probably the first to have recognised it as such. If anyone has found or used the diary before, or is aware of any citation of it in a book or article, I would be interested to hear from you.

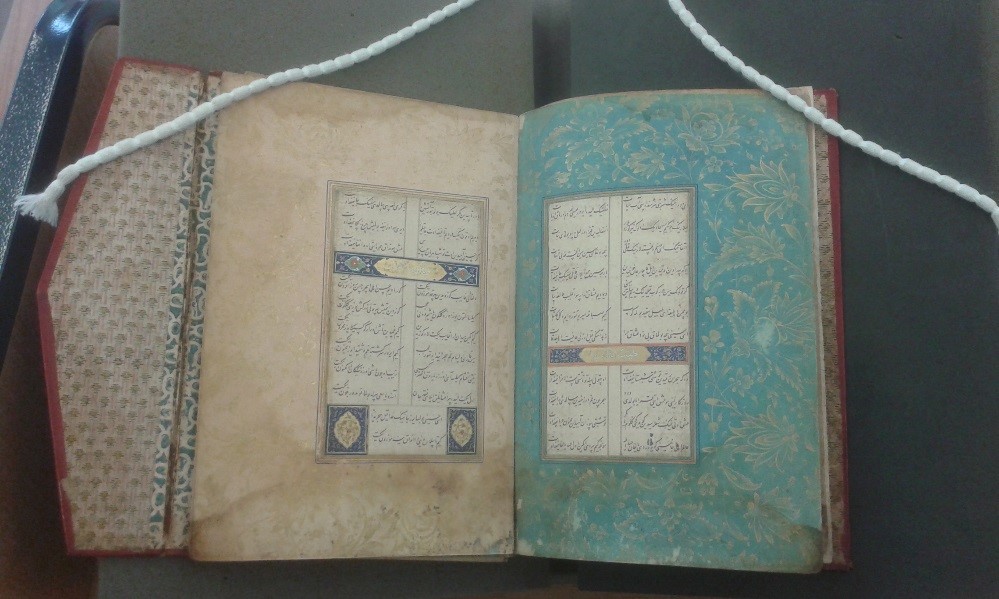

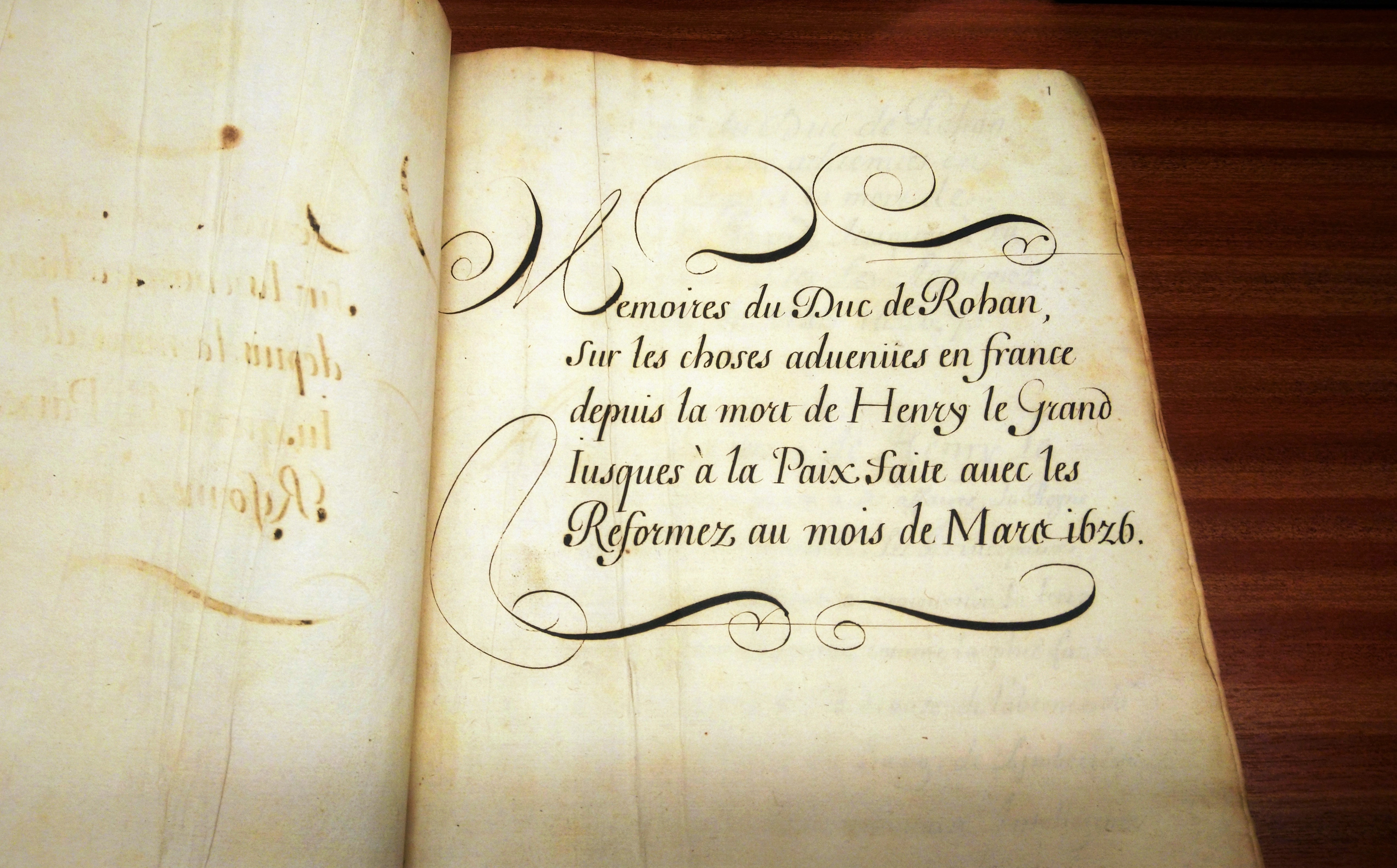

Henri de Rohan was a member of one of the most powerful families of Britany, in Western France. He used to go hunting with King Henri IV, who was his first cousin once removed. Raised as a Protestant, Henri II de Rohan became the Huguenot leader in the Huguenot rebellions that took place after Henri IV’s death, from 1621 to 1629.

Henri de Rohan was a member of one of the most powerful families of Britany, in Western France. He used to go hunting with King Henri IV, who was his first cousin once removed. Raised as a Protestant, Henri II de Rohan became the Huguenot leader in the Huguenot rebellions that took place after Henri IV’s death, from 1621 to 1629.

The site includes a general introduction to the archives held by the Oxford colleges, individual pages on most of the colleges (with further links to catalogues etc.) and links to associated archives in the City and University. There is also an FAQ page, a glossary of all those odd Oxford terms, and a bibliography. The site will be enhanced and updated regularly.

The site includes a general introduction to the archives held by the Oxford colleges, individual pages on most of the colleges (with further links to catalogues etc.) and links to associated archives in the City and University. There is also an FAQ page, a glossary of all those odd Oxford terms, and a bibliography. The site will be enhanced and updated regularly. f a rare book (we have traced a handful of Gallen almanacs in the Bodleian, and none for 1667), has become a unique manuscript as it contains a diary of Jeffrey (or Jefferay) Boys of Betteshanger, Kent for the year 1667. The

f a rare book (we have traced a handful of Gallen almanacs in the Bodleian, and none for 1667), has become a unique manuscript as it contains a diary of Jeffrey (or Jefferay) Boys of Betteshanger, Kent for the year 1667. The