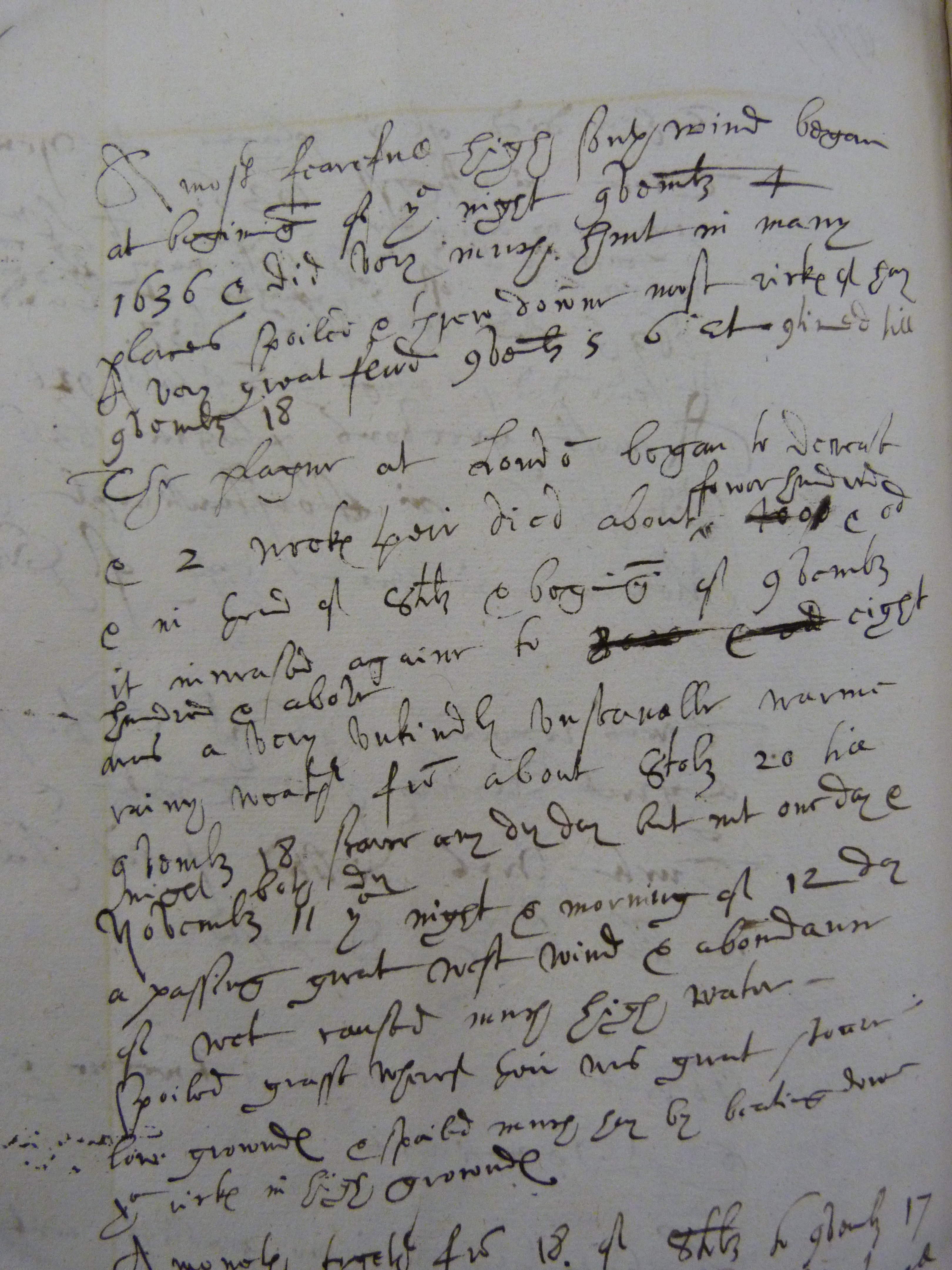

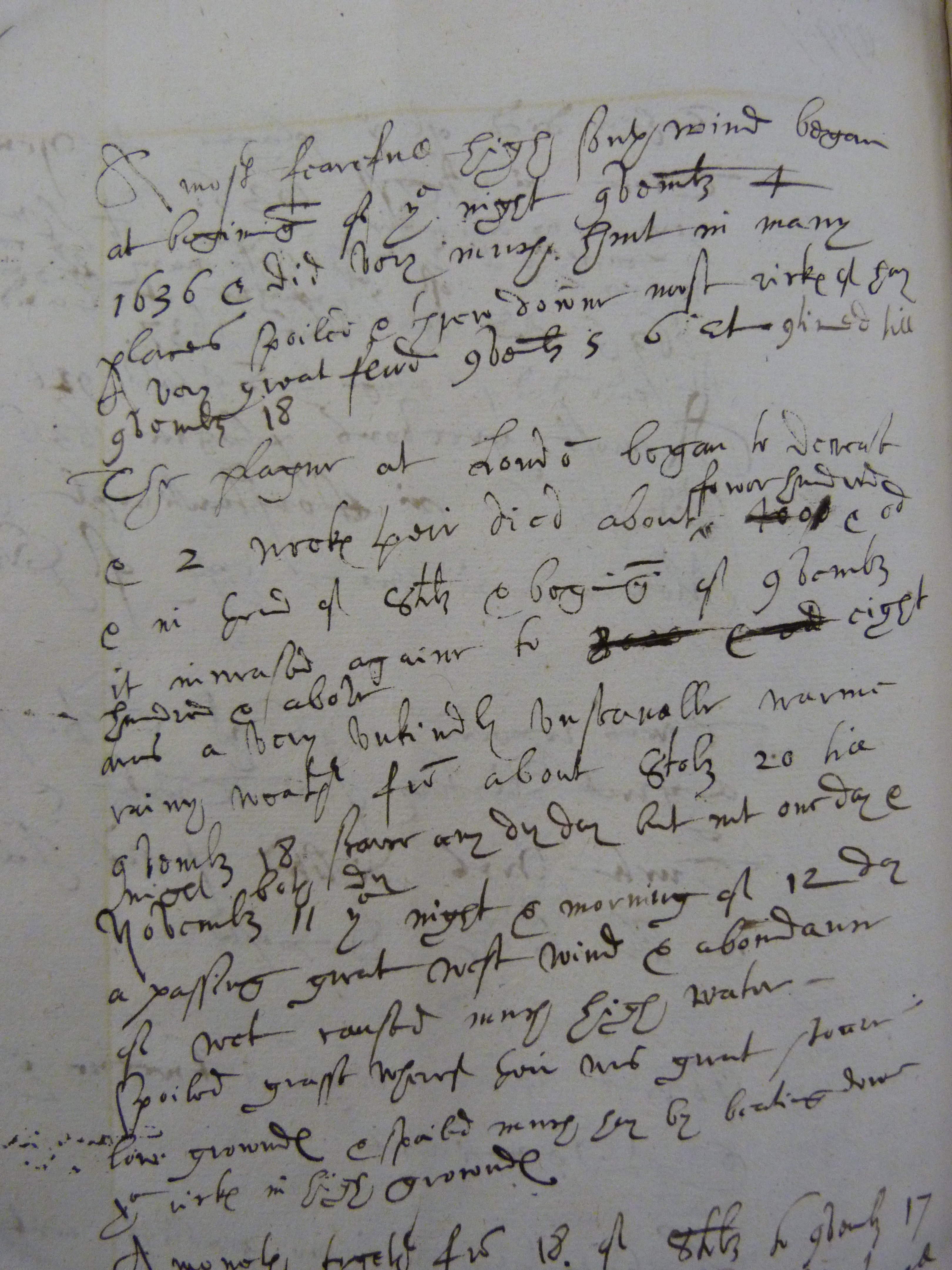

In this time of rain and flood it is interesting to see how an Oxfordshire clergyman recorded unusual weather in the 1630s. MS. Top. Oxon. c. 378 is a diary of Thomas Wyatt, rector of Ducklington and vicar of Nuneham Courtenay. His manuscript volume began life as a chronicle of the kings of England, but the extraordinary events of the reign of Charles I caught up with him, and in the 1630s the volume becomes a diary recording contemporary happenings.

Wyatt also records exceptional weather and its effects on farming and prices. These are taken from entries in 1635-7. It would be interesting to know if anyone can explain the rain of wheat, or if this phenomenon is recorded elsewhere.

[p. 275]

‘In Decemb[er] 21 [1635] a pretty snow covered the grow[n]d wthout any drift lay wth hard frost about 7 dayes. A very ope[n] misty rainy January very warme wth 3 or 4 dayes small frost rest all ope[n] & a great flood.

Jan: 30. 1635 [1636 New Style]. betwixt 7 & 8 of the clock it thundred & lightened fearfully & tempestuously wth high wind wch blew downe the top of Witney Steeple did much hurt to the church ther pulled downe the whole spire. …

[p. 280]

A most fearefull high south wind began at begin[n]ing of the night 9vemb[er] 4 1636 & did very much hurt in many places, spoiled & threw downe most rick[es] of hay. A very great flud 9ve[m]b[er] 5, 6 etc [con]tinued till 9vemb[er] 18.

The plague at Londo[n] began to decrease & 2 week[es] their died about fower hundred & od & in thend of 8tob[er] & begi[n]ing of 9vemb[er] it increased againe to eight hundred & above.

Twas a very unkindly unseanable [presumably unseasonable] warme rainy weath[er] fro[m] about 8tob[er] 20 till 9vemb[er] 18 scarce any dry day but not one day & night both dry.

Novemb[er] 11 the night & morning of 12 day a passing great west wind & abondance of wet caused much high water – spoiled grasse wherof their was great stoare in low grownd[es] & spoiled much hay by beating downe the rick[es] in high grownd[es].

A moneth togeth[er] fro[m] 18 of 8tob[er] to 9vemb[er] 17 fro[m] one chang of the moone to anoth[er] [con]tinuall raine & wind & warme unhealthy weath[er] the like not in remembrance & an extraordinary flood but 9vemb[er] 26 it began to be fayre & frost very hard at end of 9vemb[er] & till Decemb[er] 7 & the[n] a snow half foot deep the 8 to the 9, 10, 11 the[n] raine & it thawed & was a very deep fearefull water. …

[p. 281]

…

The 14 of Decemb[er] after some snow & frost ut supra. Whe[n] it thawed there was a most fearefull sodaine deepe water. It did very much hurt in Witney, drowned & carried away hay & corne, did much hurt to a diars howse upo[n] the water. People cold not go fro[m] church to their howses about the bridg wthout daung[er]. Went up to the middle in many howses, drove[?] downe great trees etc. …

[p.283]

A rumour was spread in April 1637 that in a place in Gloucestershire it rained wheate & afterward[es] some said that their fell an haile & the hailestones lay upo[n] the grownd of the forme of wheate cornes. Much speech that it rained wheate in very many places. …’

***

While on the subject of flooding, a few people have asked what the document is that forms the background to the Historical Archives and Manuscripts blog. It is from a sketch of the battle of Sedgemoor 1685, MS. Ballard 48, fol 74. Sedgemoor is on the Somerset Levels, much in the news at present. The plan was photographed for the Rediscovering Rycote website.

-Mike Webb

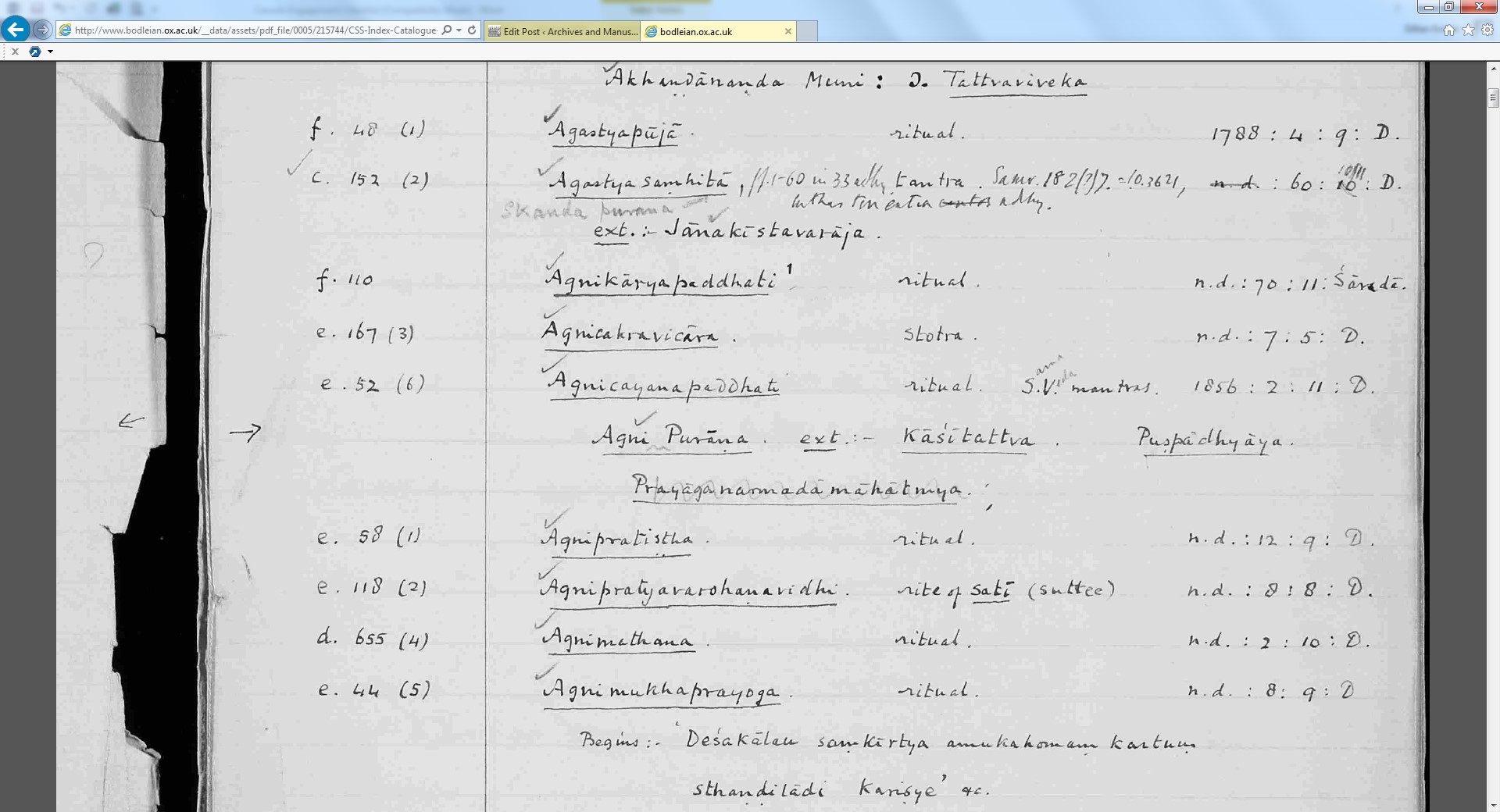

On 20th December, the Bodleian’s Clay Sanskrit Librarian, Dr. Camillo Formigatti, was pleased to be able to announce the launch of a complete digital version of the Index Catalogue of MSS. Chandra Shum Shere by T. Gambier Parry, revised and completed by E. Johnston. This small project was made possible by a generous grant from the Max Müller Memorial Fund.

On 20th December, the Bodleian’s Clay Sanskrit Librarian, Dr. Camillo Formigatti, was pleased to be able to announce the launch of a complete digital version of the Index Catalogue of MSS. Chandra Shum Shere by T. Gambier Parry, revised and completed by E. Johnston. This small project was made possible by a generous grant from the Max Müller Memorial Fund.