Percy Manning (1870-1917), an Oxfordshire antiquarian, archaeologist, and local historian, bequeathed his collection of drawings and prints, photos and detailed notes on everything from sports and pastimes to local folklore (and much more besides) to the Bodleian Library, while his archaeological collections went to the Ashmolean and Pitt Rivers Museums.

To mark the upcoming centenary of his death, the Bodleian is contributing to a mapping project that will pinpoint these collections against the places they relate to, and this involves adding more details to our existing catalogue.

This collection is full of delights, from 18th-century prints of rural idylls that are now thoroughly built-up Oxford suburbs to detailed notes on Oxfordshire dialect words and obscure local festivals.

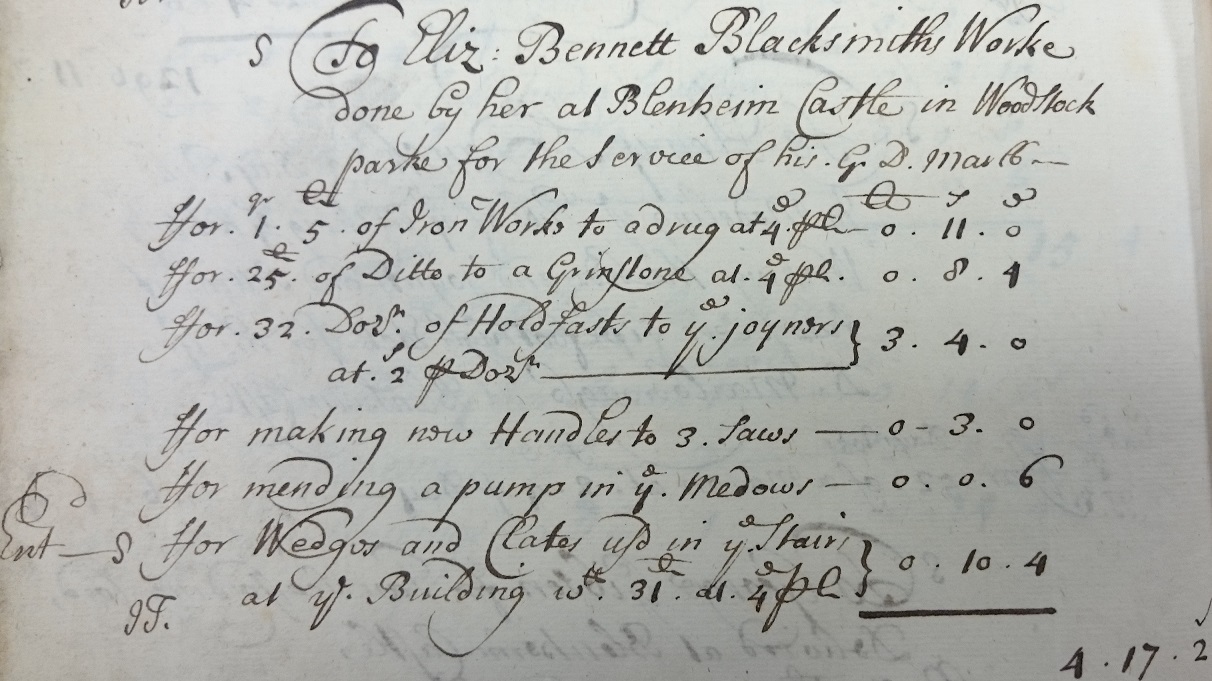

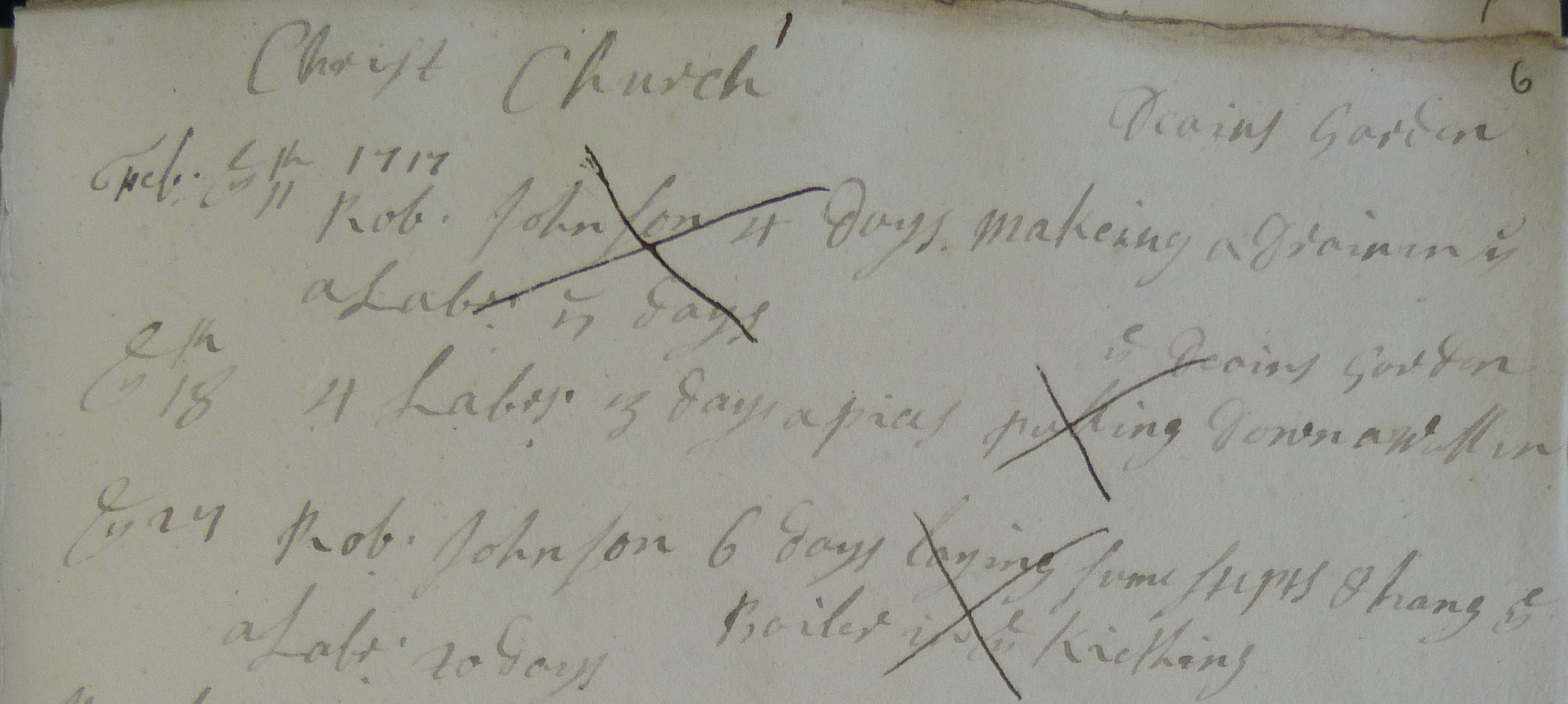

MS. Top. Oxon. c. 230, fol. 45v – Click to enlarge

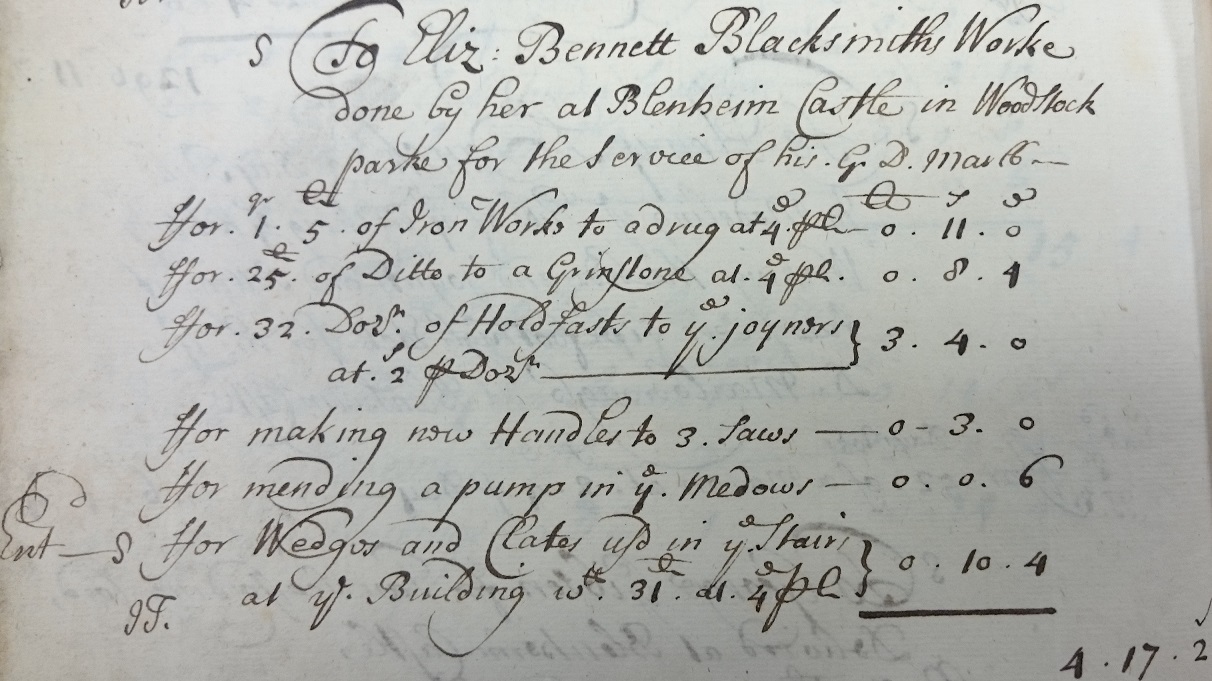

And this pleasing thing, the last entry in a 1708 account book that records building and landscaping work done on the then-unfinished Blenheim Palace in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, only 3 years into what would be an eyewateringly expensive 29-year construction project.

An account of blacksmithing work done in December 1708 by Eliz[abeth] Bennett at Blenheim ‘Castle’, her job included making 32 dozen holdfasts for the joiners (at 2 shillings a dozen), making new handles for three saws, mending a pump in the meadows, and making wedges and clouts (patches or plates) used in the stairs. But in addition to making items for a fixed price, she also charged for work by the pound weight. Twenty five pounds of iron works for a grindstone at 4 pence a pound earned her 8s 4d (100 pence total) and 31 pounds of wedges and clouts, also at 4 pence a pound, made her 10s 4d.

The total for what would have been several days or weeks of highly skilled work? 4 pounds, 17 shillings, 2 pence. Not bad at all if you compare it to a female servant’s income at about that time – maidservant Sarah Sherin made £4 a year in 1717, while in the farming world, a female labourer called Goody Currell was paid 4 pence a day at an Oxfordshire farm in 1759, fifty years later.

Elizabeth appears three times in this account book, which only covers the outlay on Blenheim from October to December 1708. In October (fol. 9v) she had a more lucrative commission, earning a handsome £8 12s 9d doing very similar work, including another 12 dozen holdfasts (this time, puzzlingly, at a mere 6d per dozen, a quarter of the amount charged in December – perhaps they were a simpler design?). She also made small cramps at 3½d per pound: over two hundredweight of small cramps which, needless to say, is a lot of small cramps, earning her £3 19s 0d.

Nothing has made me so grateful for decimalisation as checking the maths of an early modern accountant. Elizabeth made precisely 2 hundredweight, 1 quarter, and 19 pounds of small cramps in October. That’s an astonishing 271 pounds of metal work. 3½d per pound earns her 948½ pence. And with 240 pence in a pound (20 shillings in a pound, 12 pence in a shilling) that’s… well, have fun working that one out. By my reckoning it comes to £3 19s and 0.4d, so they seem to have shorted her a farthing or so. I had the benefit of a digital calculator, however. Kudos to Mr Henry Joynes, the architect who signed off on these accounts.

In November, Elizabeth made over £14 making more small cramps (a lot more – 767 pounds total) and 12 ‘gudgeons’, which the Oxford English Dictionary tells me means:

A pivot, usually of metal, fixed on or let into the end of a beam, spindle, axle, etc., and on which a wheel turns, a bell swings, or the like

But how much would a male blacksmith have been making? Well, luckily, the account book also has entries for a John Silver, Blacksmith, who earned himself the grand sum of £46 9s 9d in October, and then £12 9s 9d in December. Interestingly, however, he was paid exactly the same pound rate of 4d to make wedges and clouts (but was paid 4d a pound to make holdfasts for the joiners, rather than being paid by the dozen). Plus he, like Elizabeth, was paid 3½d per pound to make small cramps. Was this a smiths’ guild-mandated price? Or perhaps the result of a tendering process: did Elizabeth and John simply offer the lowest bids? Would they have charged more than this usually, or about the same?

Poster for the 1898 National Exhibition of Women’s Labour, Netherlands (Gemeentemuseum, The Hague). Uploaded to wikicommons by Jan Toorop.

And as for who Elizabeth Bennett was? An interesting puzzle! It isn’t so unusual to come across craftswomen in this period and earlier – there’s a picture of a woman forging a nail in the 14th-century Holkham Bible – and the work of women silversmiths like Hester Bateman is extremely collectible to this day. Like Hester, it’s likely that Elizabeth was a widow carrying on her husband’s trade, but there are no Bennetts listed on this (very unofficial) directory of Oxfordshire blacksmiths, and no Bennetts working near Oxfordshire either. Perhaps she was a member of a local craft guild – possibly an Oxford guild? – but surviving records are poor (although a good chunk of the what’s left is, conveniently enough, here at the Bodleian). Perhaps she took an apprentice after 1710, in which case, there should be a registration record. And there’s always parish records, of course, to, try and track down her baptism and death dates, and any marriages. I for one, would love to know more!

This blog post is written as part of our project to increase the accessibility of the Bodleian's Percy Manning holdings in the run up to the centenary of Manning's death in 2017. We are grateful to the Marc Fitch Fund for its generous support of this project.