As the horseracing world gets ready for this year’s Grand National on 13-15 April, the University Archives’ blog this month looks at the relationship between horses and students at Oxford in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

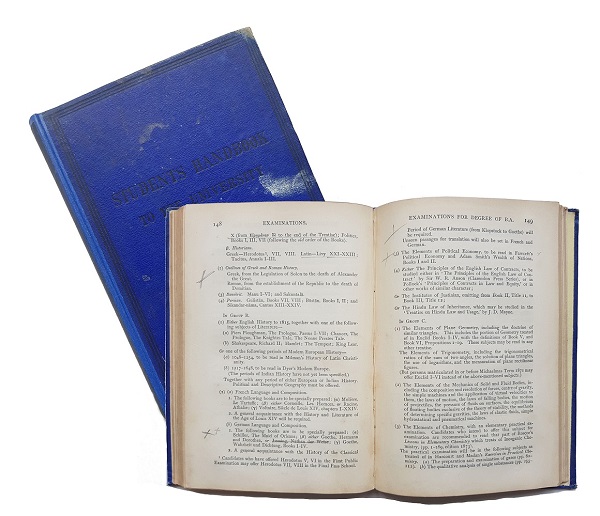

The life of an undergraduate student at late-eighteenth-century Oxford was not what we would call arduous. The University had become rather (in)famous by this date for its narrow and undemanding curriculum, and lax examination standards. Its academic reputation was poor, seen as a place where the sons of aristocracy could spend a few years in a kind of finishing school, enjoying themselves before going out into the adult world. Lectures were not compulsory and as there were no written exams, and only one final (oral) examination which no-one failed, there was little pressure on students to study hard. No wonder, then, that students had free time on their hands.

For some students, horses became a big part of this free time. Horses had a variety of uses: both as providing entertainment and sport, and as a means of transport and travel, enabling students to leave the confines of Oxford and get out into the countryside (and into the country pubs) around it.

Most students, if they needed a horse, simply hired one from one of the many stables in Oxford which had grown up to support this thriving market. Famous stable keepers of the the time included Charley Symonds in Holywell Street (whose stables, at one point, could accommodate 100 horses) and Samuel Quartermaine in St Aldates (who apparently owned a Grand National winner). The more well-off students kept their own horses in Oxford, however, and paid these stable keepers (at great expense) to look after their horses so they could use them whenever they wanted to.

In order to keep a horse at Oxford, students needed the permission of both the Vice-Chancellor and their college. Keeping a horse without permission was not permitted by the University authorities. This was to try to enable the University to control the keeping of horses by its students, and to limit the damage that the students could do with them.

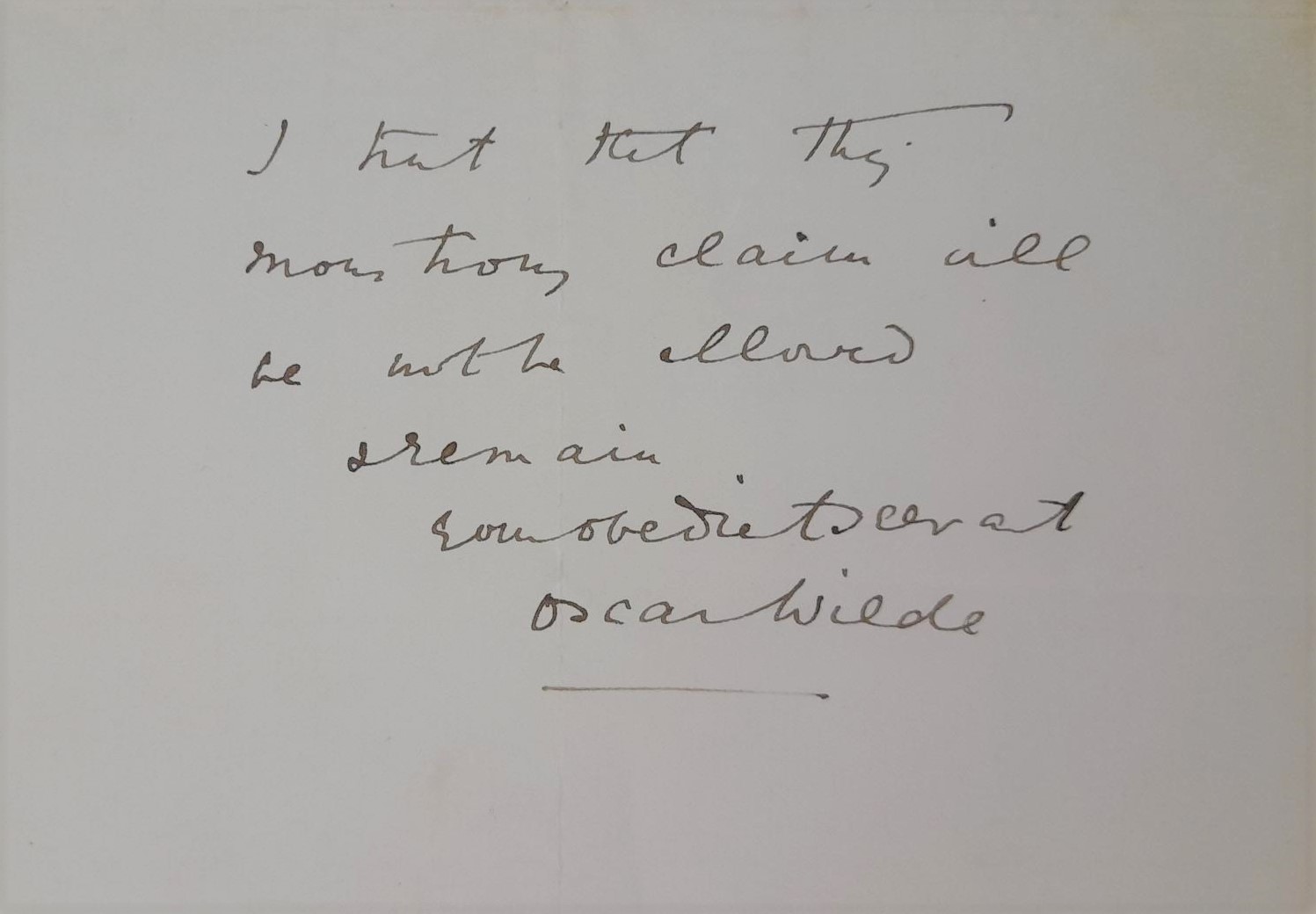

The University Archives holds a small number of records concerning the keeping of horses and the means by which students secured permission to do so. A parent, usually the student’s father, wrote to the Vice-Chancellor personally to request that his son could keep a horse. The request also had to be approved by the student’s college. The records here include a number of these letters from parents and colleges. One student in 1788, Thomas Bartlam of Worcester College, almost literally had a note from his mum.

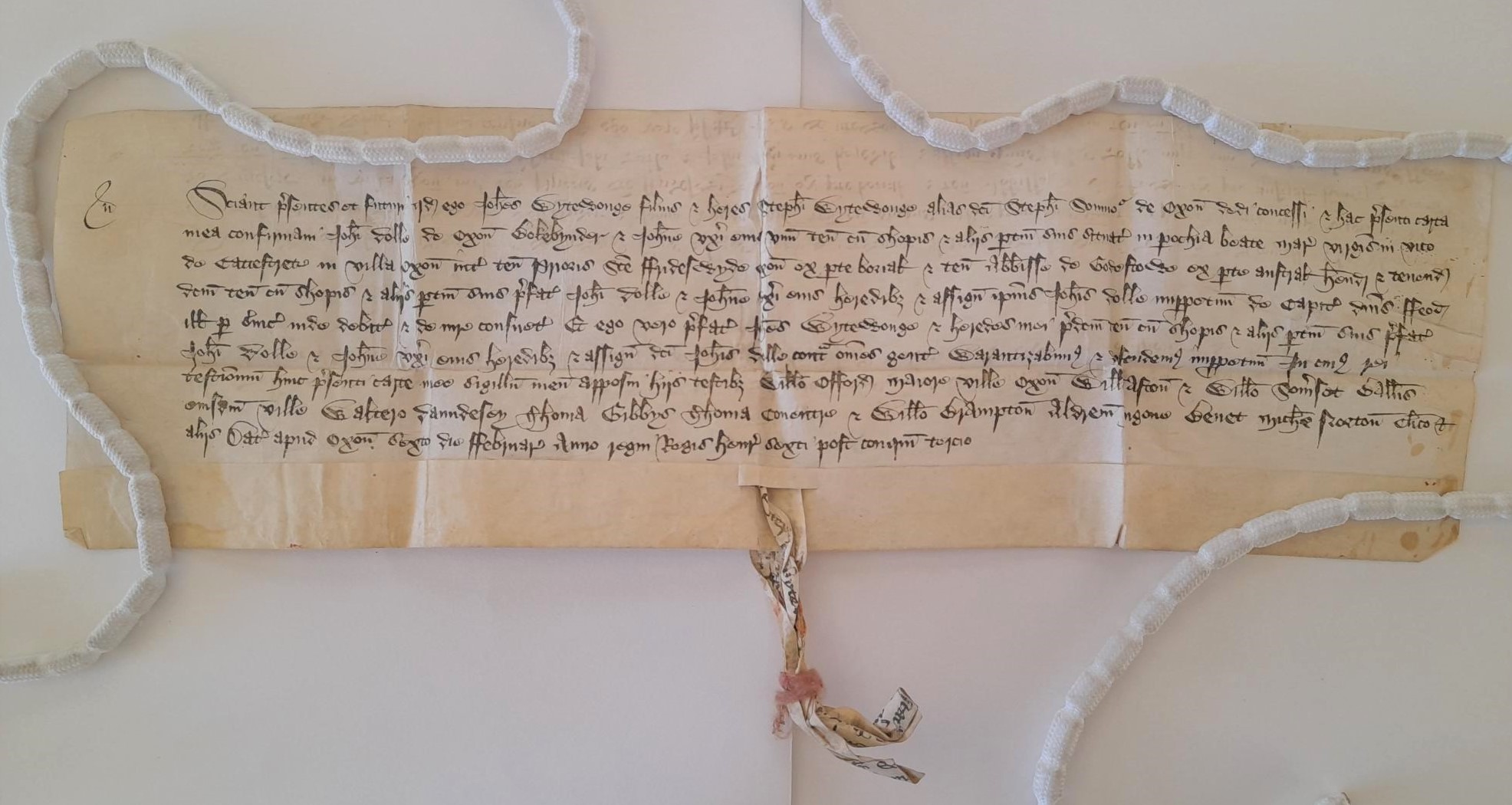

Letter giving permission for Thomas Bartlam, Worcester College, to keep a horse, 1788 (from OUA/MR/8/1/2)

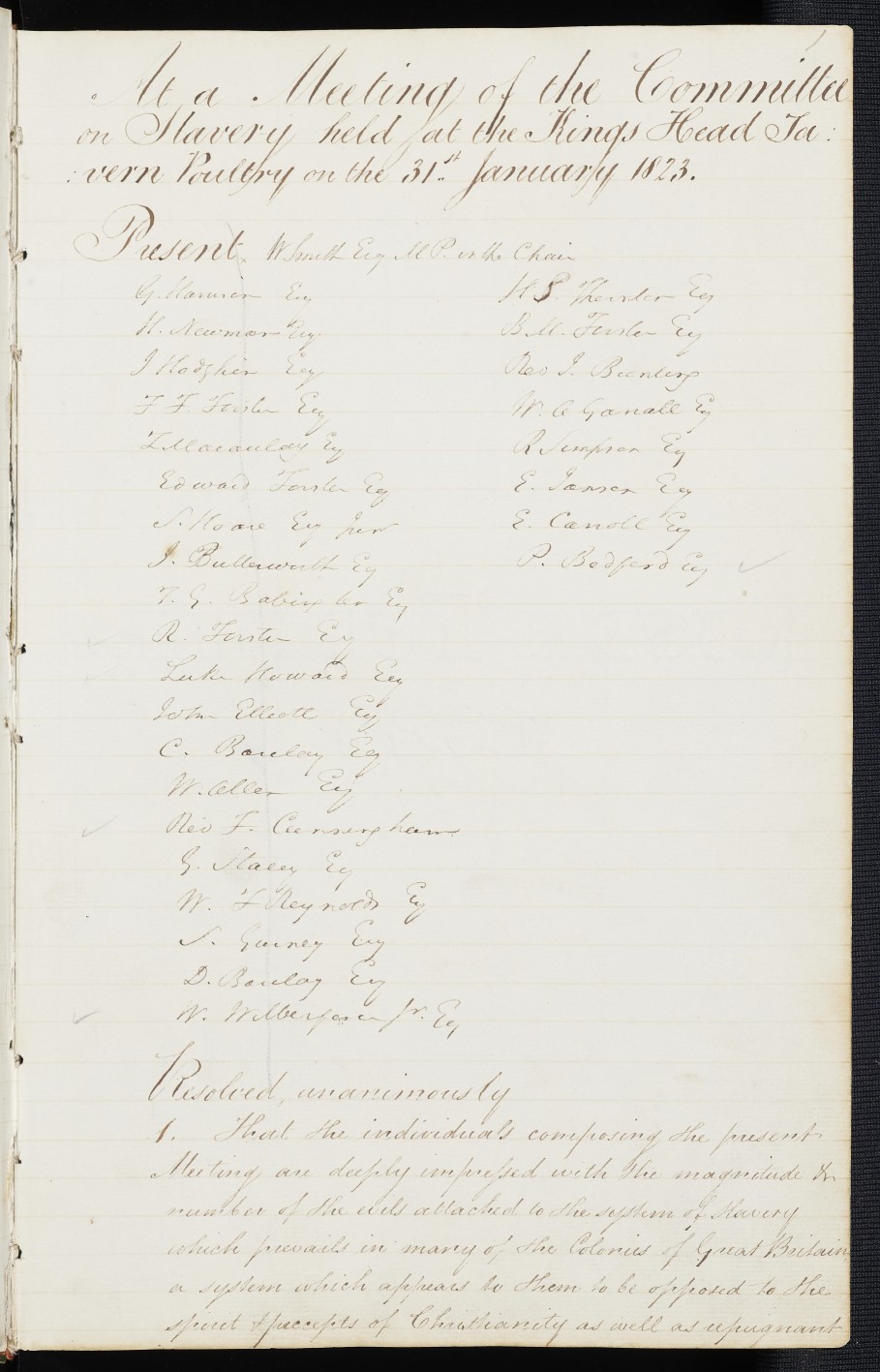

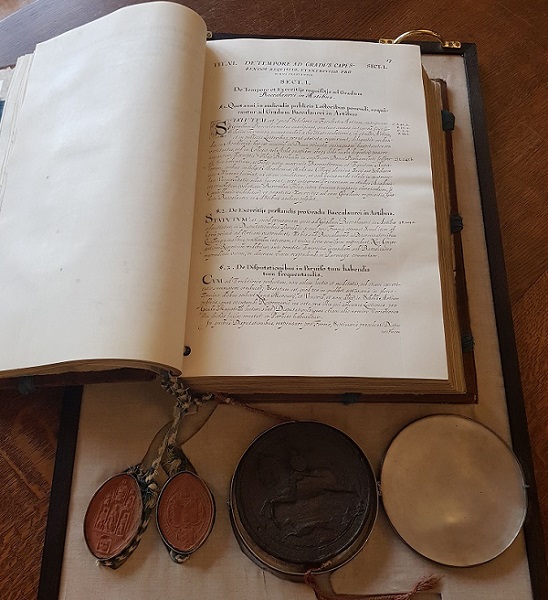

As expected, these students were of the richer variety: those who could afford to pay someone else to keep their horse for the duration of the term. They were also rich enough to apply, in the same way, to keep their own servants at Oxford. Rather unfortunately, the keeping of both horses and personal servants was administered by the University in the same manner. The records in the Archives include a register, arranged by college, of the names of students who successfully applied for permission (‘veniam impetravit’) to keep either a horse or a servant. Next to the names of the students were two columns – one for horses (‘Eq’, short for ‘equus’ the Latin word for horse) and one for servants (‘Serv’) giving the numbers kept of each.

Names of students of Merton College given permission to keep horses and servants, 1786-1808 (from OUA/MR/8/1/2)

As time went on, the register also began to be used to record permission to keep vehicles (ie carriages to go with the horse). Horse-drawn vehicles caused the University authorities great consternation as they tried to stop students driving a range of carriages (gigs, tandems and ‘phaetons’) fast and furiously around the city.

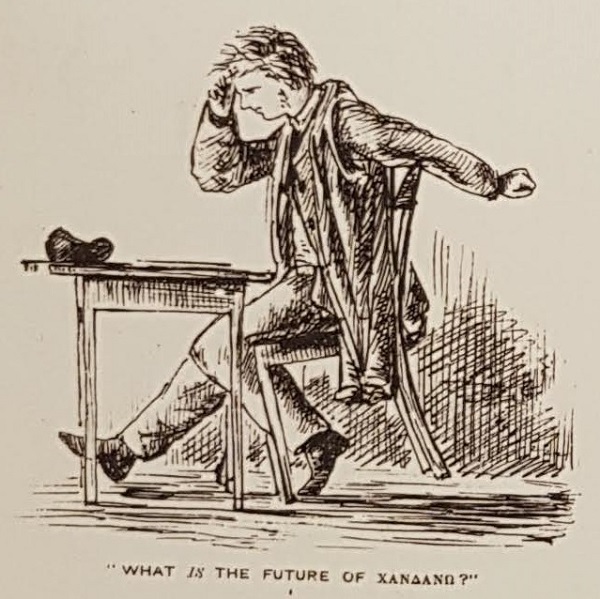

When applying for permission to keep a horse, many students claimed that their doctor had recommended riding for their ‘health’. The city of Oxford was probably not the cleanest place in the late eighteenth century, and a ride out into the fresher air of the Oxfordshire countryside was no doubt of benefit, but there is reason to be cynical about the truth of all of these claims. The University’s statutes governing undergraduate behaviour (De Moribus Conformandis) made only one exception to the general rule of no horses, and that was for students in poor health. As a result, it appears to have become a bit of a loophole, exploited as a convenient way to guarantee that permission would be granted.

Apart from the freedom to travel, which a horse would give, the most likely (and coincidentally most illicit) reason why a student might want to keep on in Oxford was for sport. The undergraduate sporting scene at this time was very different from today. Organised sport did not exist – neither the University nor the college provided facilities for it – and sports clubs did not start to emerge until much later in the second half of the nineteenth century. Instead, student sport was very much based on individuals’ personal wealth and the conspicuous use of it.

Having managed to get their horse to Oxford, the students then used it to indulge in expensive luxury pursuits such as hunting and horse riding in the countryside nearby. Nearly all such pursuits were prohibited by the University, its statutes specifically forbidding students from pursuing most horse-related activities. As well as outlawing the driving of certain horse-drawn vehicles, the statute De Moribus Conformandis banned students from indulging in pastimes which involved money, or which could cause injury or a spectacle. The one sport which flouted nearly every one of these rules was horse racing.

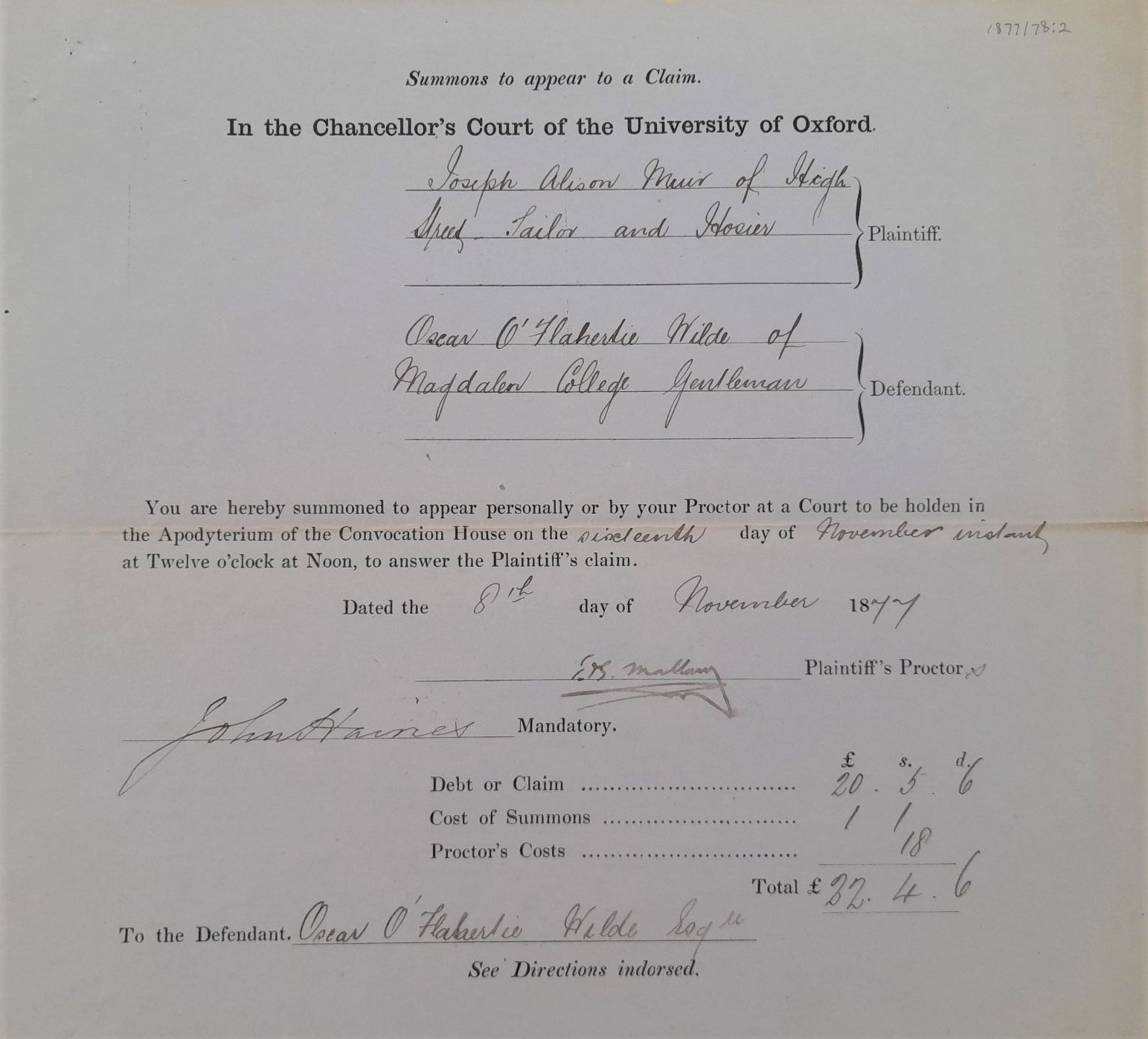

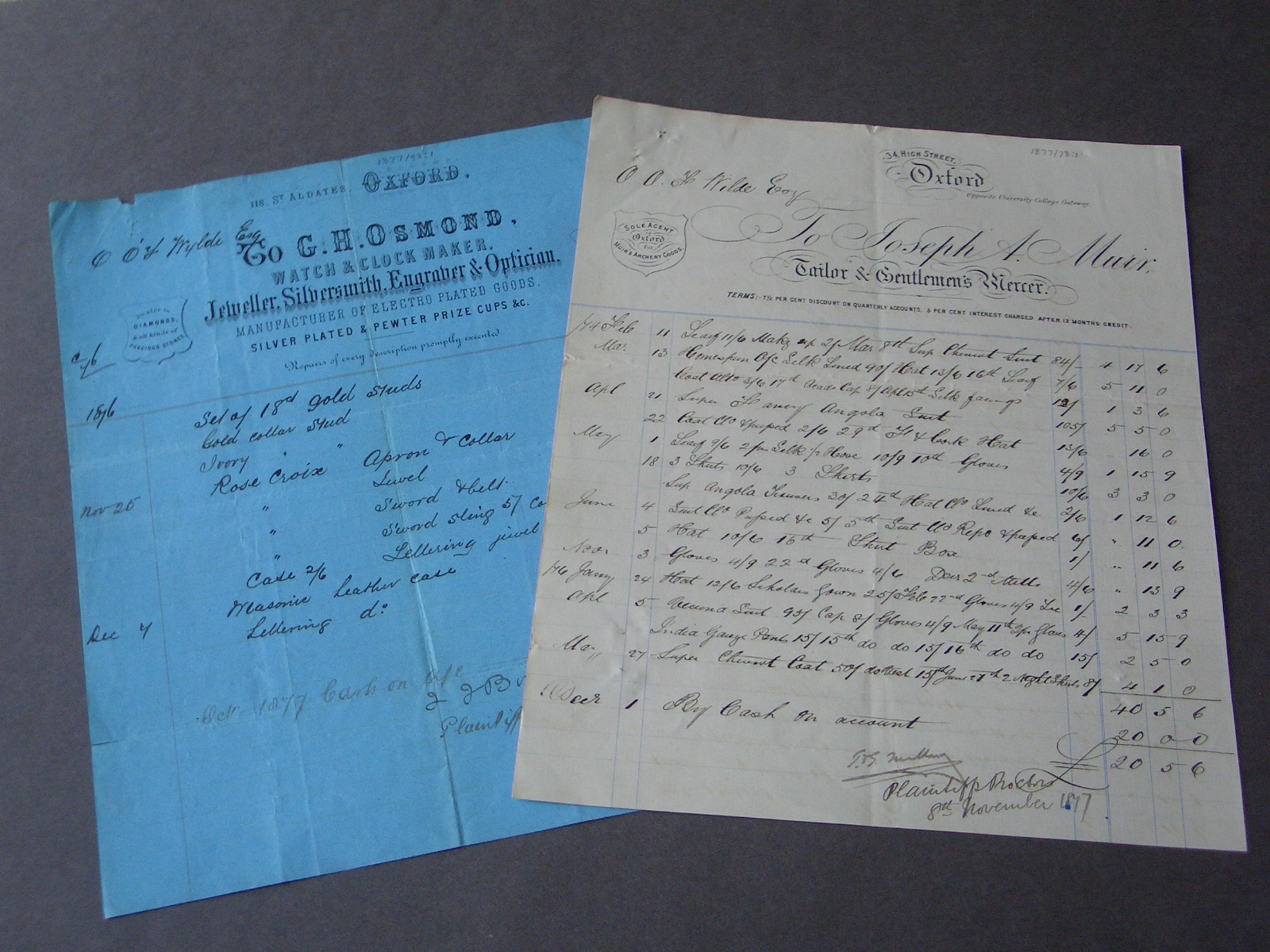

Taking part in horse racing, or even just spectating, combined many of the worst excesses of student behaviour, the University thought, and it fought against it. Although the arrival of the railway in Oxford in the 1840s had made it easier for students to get to racecourses (despite the University trying to prevent them from getting there by banning the use of stations such as Ascot), students made their own entertainment closer to home, holding horse races in and around the city.

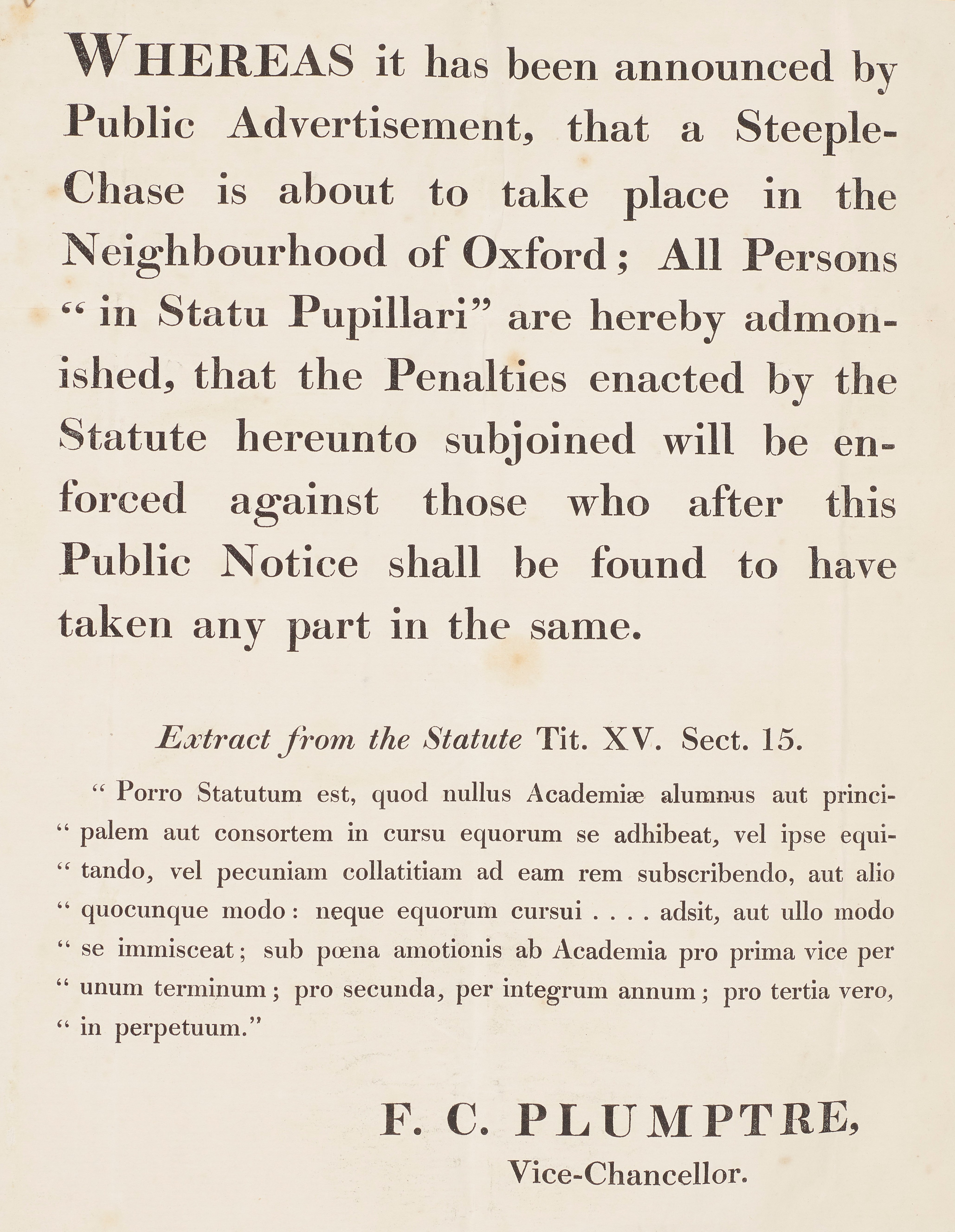

The University responded by putting up notices warning students not to take part. Posted on college walls and doors, these printed notices were the chief means of communication by the University to students at the time, usually reprimanding them for bad behaviour. Issued under the name of the Vice-Chancellor or Proctors, they described the offending behaviour before threatening punishment under the relevant part of the statutes. Punishments were usually in the form of fines, but could involve expulsion for serious or repeat offenders. Some notices even threatened the townspeople who aided and abetted the students.

A small number of these notices survive. One reports the practice of horse racing in Port Meadow and comes down hard on both those taking part as well as those simply watching. Another mentions an upcoming steeplechase which seems to have been widely publicised. Taking pre-emptive action, the University threatens those planning on participating with removal from the University (‘amotionis ab Academia’).

By the second half of the nineteenth century, things were changing. Steeplechasing became respectable in the 1860s when it gained ‘blue’ status (ie formal Oxford-Cambridge steeplechasing contests were established). Relations between students and the University authorities improved as sports clubs began to be established and organised team sports (such as cricket and rugby) replaced private activities. And the number of idle gentry amongst the student body decreased as the academic rigour of the University’s curriculum and examinations increased. The respite for the University authorities was brief, however. Within a few decades, the motor car had replaced the horse as the students’ vehicle of choice and the University had to deal with a brand new and much more dangerous problem.

Equestrianism continues to thrive at the University today, although it mostly focuses on showjumping and dressage, and not on steeplechasing across Port Meadow. Further information can be found on the University Sport equestrian website at https://www.sport.ox.ac.uk/equestrian