Whilst working on the project of retro-converting the Old Summary Catalogue (OSC), I get a unique chance to look at everything acquired by the Bodleian Libraries since 1602. This includes the academic, interesting, and a bit weird. And weird is what I’m bringing you today, hopefully offering a welcome bit of escapism.

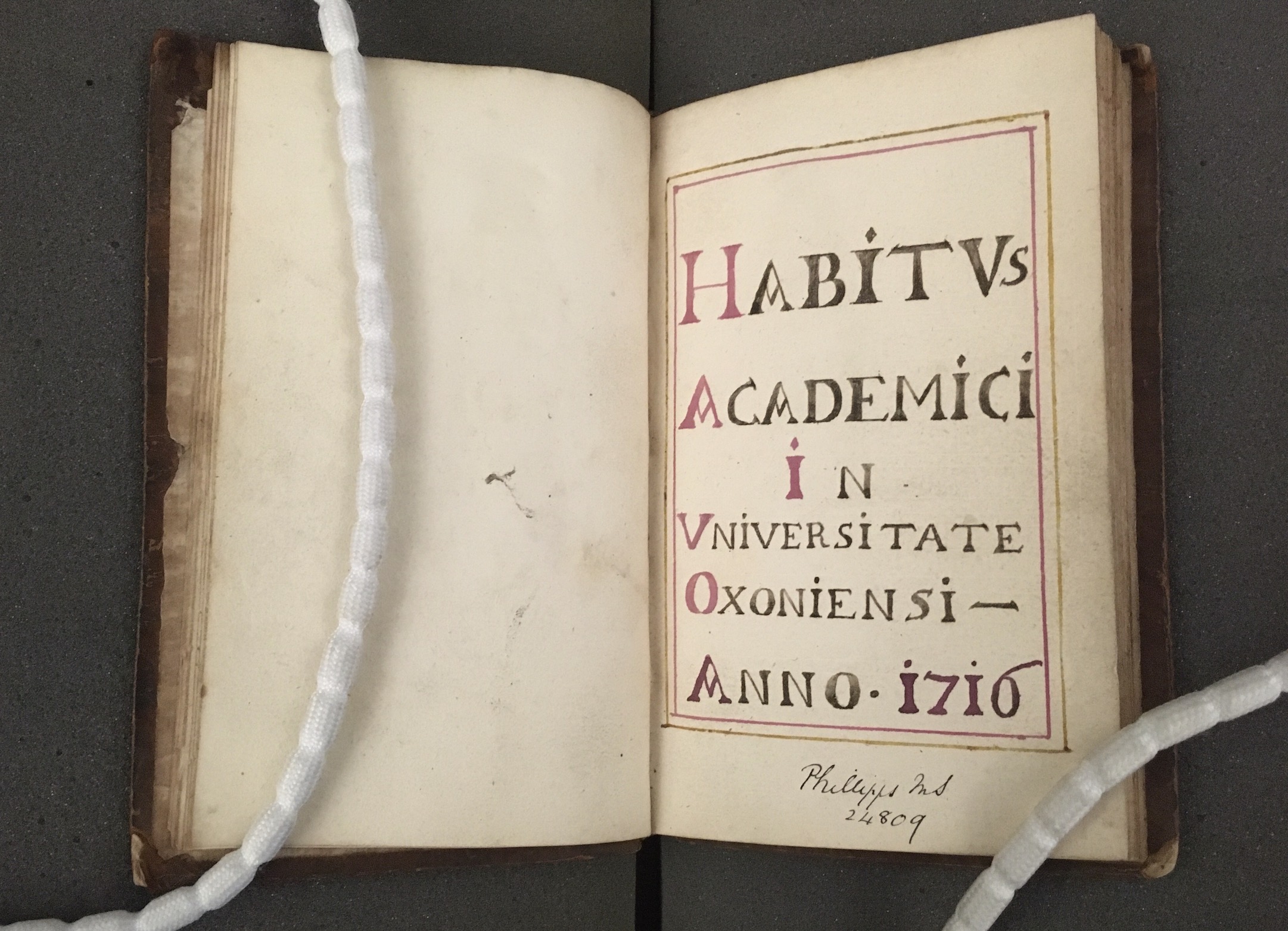

You never know what you’re going to come across each day and the item I’ve chosen to write about this time is recorded as number 3548, with the description beginning “A book of magical charms”. How could this not pique my interest? The full OSC entry is as follows:

The Newberry Library in Chicago contains a similar book of magical charms from the 17th century, for which they sought public help to transcribe in 2017 in the hope of making the various magical texts they held “more accessible to both casual users and experts”. Christopher Fletcher, the coordinator of the US based project, explained that ” both protestant and Catholic churches tried very hard to make sure that nobody would make a manuscript like this…they didn’t like magic. They were very suspicious of it. They tried to do everything they could to stamp it out. Yet we have this manuscript, which is a nice piece of evidence that despite all of that effort to make sure people weren’t doing magic, people still continued doing it.” [1] Although from a different continent, this is a great piece of evidence to show how magic, spirituality, and supposed ‘witchcraft’ continued to remain in the lives of many for much longer than the church and state would have liked to believe.

There are another three items attributed by Falconer Madan (author of the OSC and a Bodleian librarian) to the Oxford citizen Joseph Godwin, who presented this book of magical charms on the 6th August 1655. These show an interesting mixture of magic, science, and religion, that was undoubtedly prevalent – though discouraged- at the time:

– Number 3543, MS. e Mus. 173: “Copies of incantations, charms, prayers, magical formulae, astrological devices, and the like”

– Number 3546, MS. e Mus. 238: “Magical treatises” (including magic and astrology)

– Number 3550, MS. e Mus, 245: “A roll of incantations and prayers”

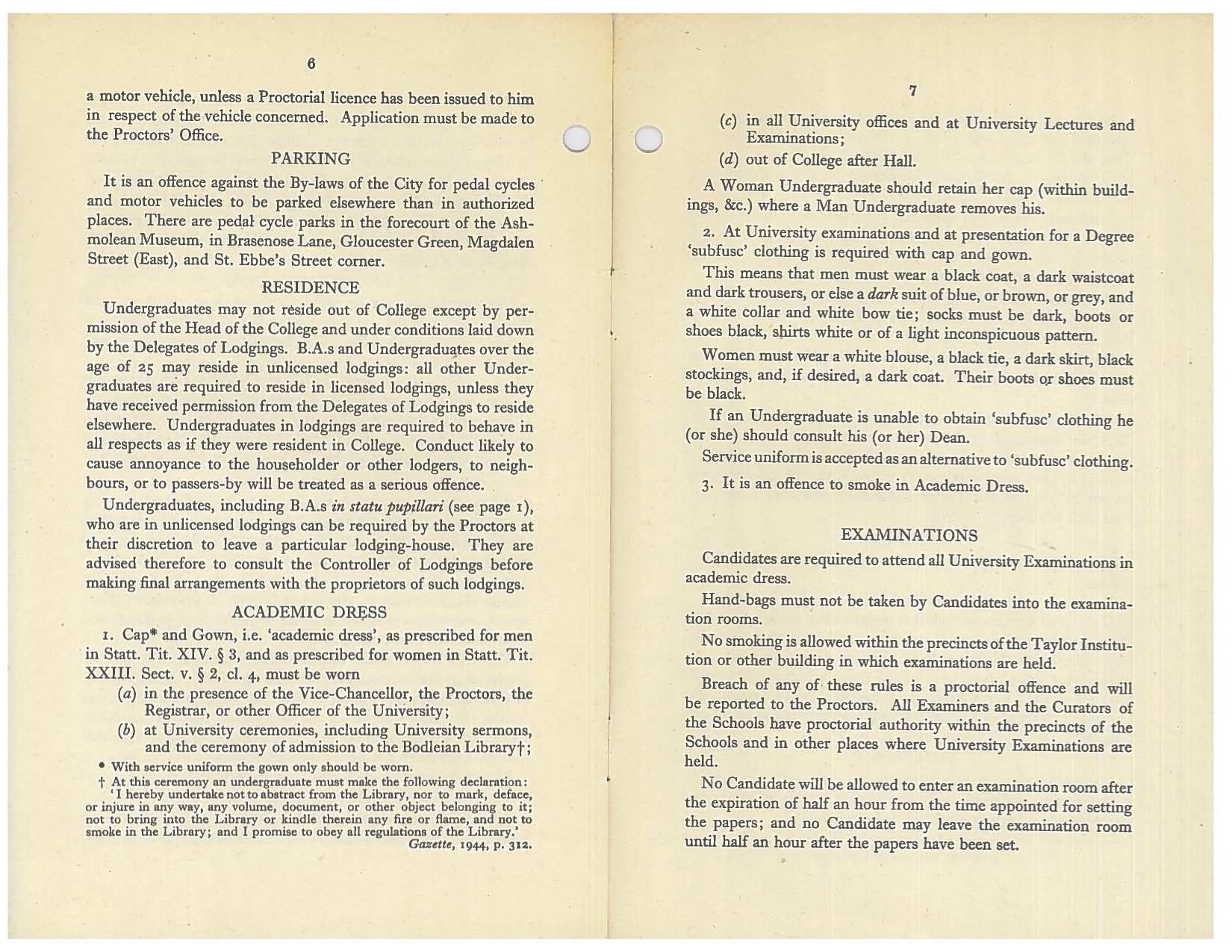

As with many archival items, we don’t know a huge amount of information about it. We don’t know much about Joseph Godwin, the donor, other than that he was a citizen of Oxford, and we can’t know whether this book of magical charms was written by Godwin or someone else. What we can assume with relative confidence is that the author of this book would have been well-educated. Literacy levels are notoriously difficult to estimate; some may have been able to read and not write, and although most information comes from those able to sign their names, they may have been able to do little else. However, in England in the 17th century, it is tentatively estimated that literacy levels were around 30% for males, potentially higher for a university city such as Oxford. [2] The fact that this, as well as the other material, is written in a mixture of Latin and English, suggests an elite education. A standardised form of written English became prevalent in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, with this replacing Latin and French in 1417 in government documents and business. [3] By the 17th century, Latin would have largely been the preserve of the clergy and academic community. A disproportionate amount of those persecuted for witchcraft were from poor and uneducated backgrounds, whereas this book provides additional evidence that those from all walks of life may have taken an interest.

Onto the object here at the Bodleian Library. One of the reasons I chose this item to write about was how much the first charm I came across made me laugh:

“A booke of Experiments taken

out of dyvers [diverse] auqthors. 1622

Anger to aswage.

Wryte this name in an Apple ya[v]a

& cast it at thine enemie, & thou shalt

aswage his anger, Or geve it to a

woman & she shall love thee.”

Now I’m no expert, but I’m going to go out on a limb and say throwing an apple at your enemy is probably not going to do wonders for repairing your friendship, even in the 17th century! Geoffrey Scare, John Callow, et al, for The Guardian in 2001, wrote about how differently we do live now, however. They began their article on witchcraft and magic in 16th and 17th century Europe with a simple truth: “‘At the dawning of the third millennium, a belief in the reality and efficacy of witchcraft and magic is no longer an integral component of mainstream Western culture. When misfortune strikes at us, our family or a close neighbour, we do not automatically seek to locate the source of all our ills and ailments in the operation of occult forces, nor scour the local community for the elderly woman who maliciously harnessed them and so bewitched us.” [4] Just like this, we do not tend to turn to magical charms in order to reverse our fortune, or solve our problems with enemies, love, or danger, as the book suggests was practiced then.

This book of magical charms is to me, a mixture of folklore, religion and spiritual belief, and I couldn’t talk about it without delving a little bit into witchcraft, which I and many others find a fascinating topic. What I found shocking when doing my research was how recent the last conviction under the 1735 Witchcraft Act was in the United Kingdom. The act repealed previous laws against witchcraft but imposed fines and imprisonment still against those claiming to be able to use magical powers. To me, witchcraft persecution is the stuff of Early Modern History classes, but it was actually 1944 when Jane Rebecca Yorke of Forest Gate in East London was the last to be convicted. [5] Whereas we may think of witchcraft now to be mostly mythical, or something a small amount of the population dabble in, the law has played a large part in punishing those who have been associated in it throughout at least the last 500 years.

The first official (and by that I mean recorded) law against witchcraft in England was in 1542. Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act, making the practice of magic a crime punishable by death. Although repealed in 1547, it was restored in 1562. An additional law was passed in 1604 by James I, a firm believer in the persecution of witches, which transferred the trials from the church to ordinary courts and thus made witchcraft trials far more commonplace. The peak of witchcraft trials took place between 1580 and 1700, usually involving lower class and older women, and the last known trials occurred in Leicester in 1717. It is estimated that 500 people in England were executed for witchcraft related offences, most of these being women. As referenced above, the 1735 Witchcraft Act, passed in 1736, repealed the laws making witchcraft punishable by death but allowed fines and imprisonment. This was repealed in 1951 for the Fraudulent Mediums Act which is turn was repealed in 2008. [6] The timeline of witchcraft makes the book of charms even more interesting, and the act of Joseph Godwin’s donation one of potential bravery (/stupidity). With witchcraft such a prevalent part of society in 1622, this object in Godwin’s home or as a donation may have led to suspicion, prosecution, and even death.

The story behind the book, we may never know, but it is a great object in itself. Here are some other interesting passages/charms I came across which provide us a unique look into belief at this time:

If you’re interested in this object, you can view it in the Bodleian Archives and Modern Manuscripts interface. Once the library reopens, it will be available to request and view in the Weston Library Reading Rooms.

[1] Katz, B., “Chicago Library seeks help transcribing magical manuscripts,” Smithsonianmag.com, (3 July 2017), URL: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/chicago-library-seeks-help-transcribing-magical-manuscripts-180963911/

[2] Van Horn Melton, J., The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

[3] “Oral and Literate Culture in England, 1500-1700,” The Guardian (20 June 2001), URL: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001/jun/20/artsandhumanities.highereducation

[4] Scarre, G., J. Callow, et al, “Witchcraft and Magic in Sixteenth-and Seventeenth Century Europe,” The Guardian (8 June 2001), URL: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001 /jun/08/artsandhumanities.highereducation

[5] “Jane Rebecca Yorke,” Wikipedia, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jane_Rebecca _Yorke

[6] “Witchcraft,” UK Parliament, URL: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/religion/overview/witchcraft/