Over the past few months we have opened up the Edgeworth Papers to share tales of the Edgeworths’ domestic concerns, love affairs, and literary lives. We now turn to consider how the public political world also impacted upon the Edgeworth circle. News of one event in Manchester two hundred years ago – and widely commemorated this month of August 2019 – reached the Edgeworth family at the comparative distance of their home in County Longford.

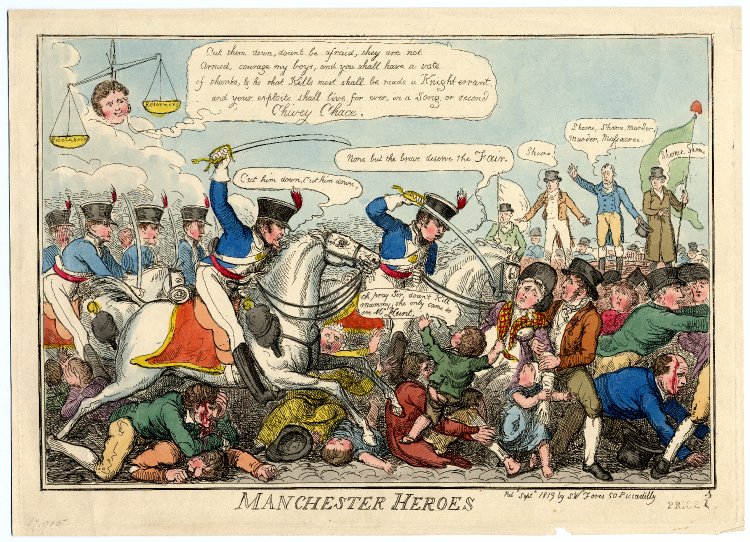

On 16 August 1819, a large crowd gathered in St Peter’s Field, Manchester, to urge for greater parliamentary representation and listen to radical speakers including ‘Orator’ Henry Hunt (1773-1835). Following the orders of magistrate William Hulton to arrest Hunt, the cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry charged into the amassed crowd (modern estimates are there were up to 80,000). The charge resulted in the deaths of approximately 18 people (including a two-year-old boy) and the injury of an estimated 400-700 more people. The Peterloo Massacre, as it became known, was a defining moment in nineteenth-century class history. It was widely reported in the newspapers and the graphic satires of the day.

The Manchester Heroes, 1819, Hand-coloured etching by George Cruikshank on paper, 250 × 350mm, © Trustees of the British Museum

The Manchester Heroes, 1819, Hand-coloured etching by George Cruikshank on paper, 250 × 350mm, © Trustees of the British Museum

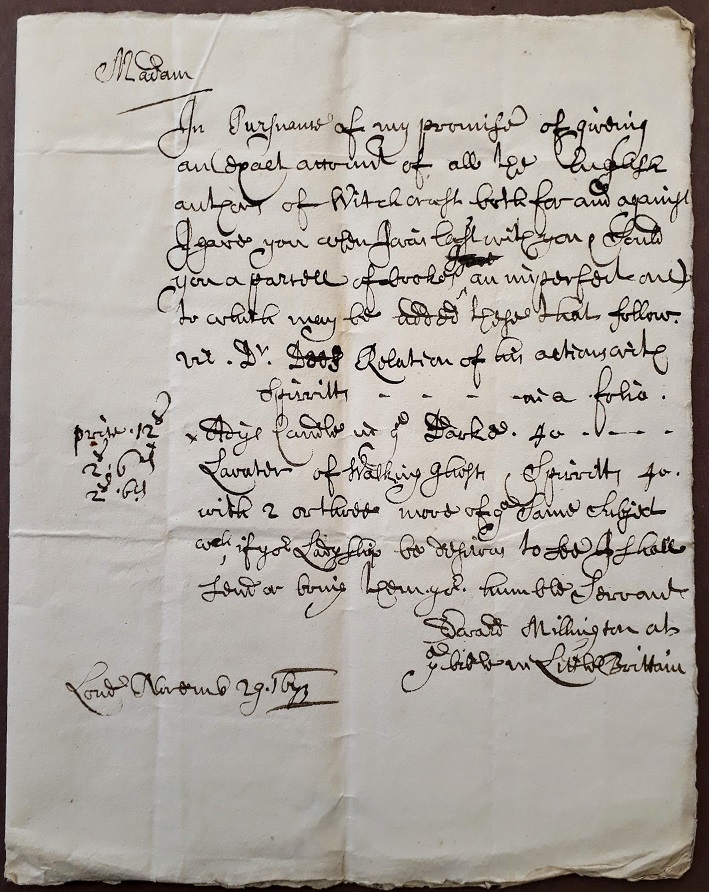

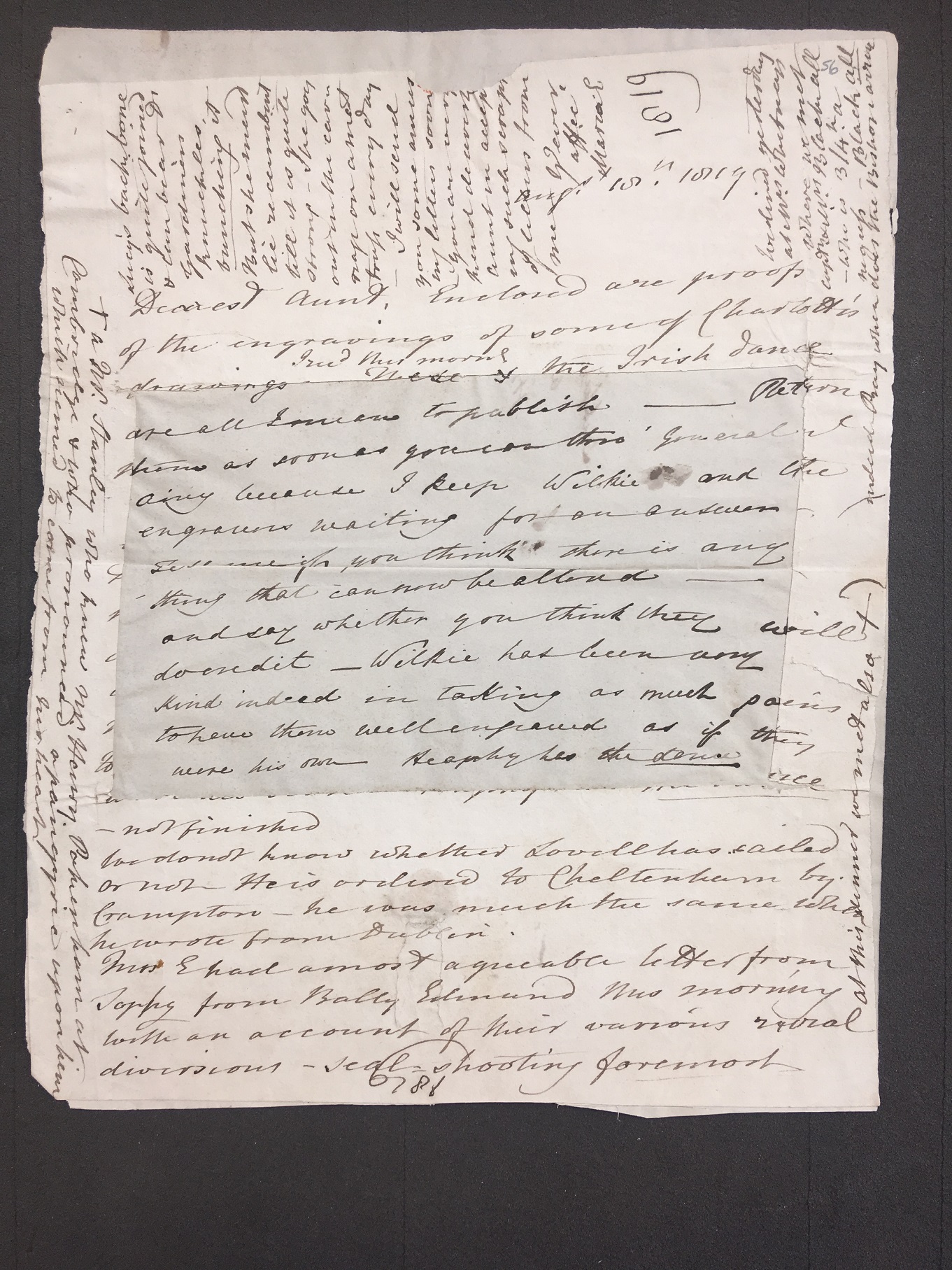

Maria mentions Peterloo in her letter to Peter Holland (1766-1855), who lived close to Manchester in Knutsford, on 27 August (MS 16087/1). The Bodleian has recently acquired this fascinating (and as yet uncatalogued) collection, comprising 145 largely unpublished letters. The collection includes 37 letters written by Maria to Holland and c.80 letters to her from his son, Sir Henry Holland (1788-1873), apparently on behalf of and in collaboration with his father. The archive also includes letters written by Henry to his father and to the writer Lucy Aikin (1781-1864). In this particular letter, Maria informs Peter Holland that she has dictated the letter to Fanny in order to save Maria’s eyesight and for his ease of reading. The letter is urgent though as she needs to know if Peter Holland is ‘dead or alive’ and his family safe following the ‘riots of mob & military’ in Manchester. We provide a transcription of the first paragraphs of the letter that relate to Peterloo.

Images of the first two pages of Maria’s Letter to Peter Holland (27 August 1819, MS 16087/1)

Transcription of first two paragraphs of Maria’s Letter to Peter Holland 27 August 1819, MS 160871

From her ‘distant view’, Maria shares her opinion on events, which she declares ‘perhaps on these occasion may chance to be the truest because the most impartial’. Maria does not support the reformist cause as it is proposed by Hunt (indeed she refers to his ‘evil designs’), and she praises the yeomanry’s ‘good intentions’, but censures their actions:

‘…their imprudent conduct they have made notorious to all the world—What an opportunity of showing that just vigor necessary to restore order they have lost by rashness – why did they not let Hunt and his followers proceed to some overt act before they began cutting and slashing? – I hope Government will forbid yeomanry to act again in any such cases – from their local feelings & from their want of discipline they are of all others the most improper to be employed.’

Maria’s concern for Holland was not only personal, but also evinces her active interest in the politics of the day. Though Maria was ‘distant’ from Peterloo, she was no stranger to political uprisings, such as the Irish Rebellion of 1798, a retaliation against British rule that resulted in the deaths of 10-30,000, which helped shape her ideas about the acceptable and proper limits of rebellion, though her progressive leanings were toward reform rather than regime change.

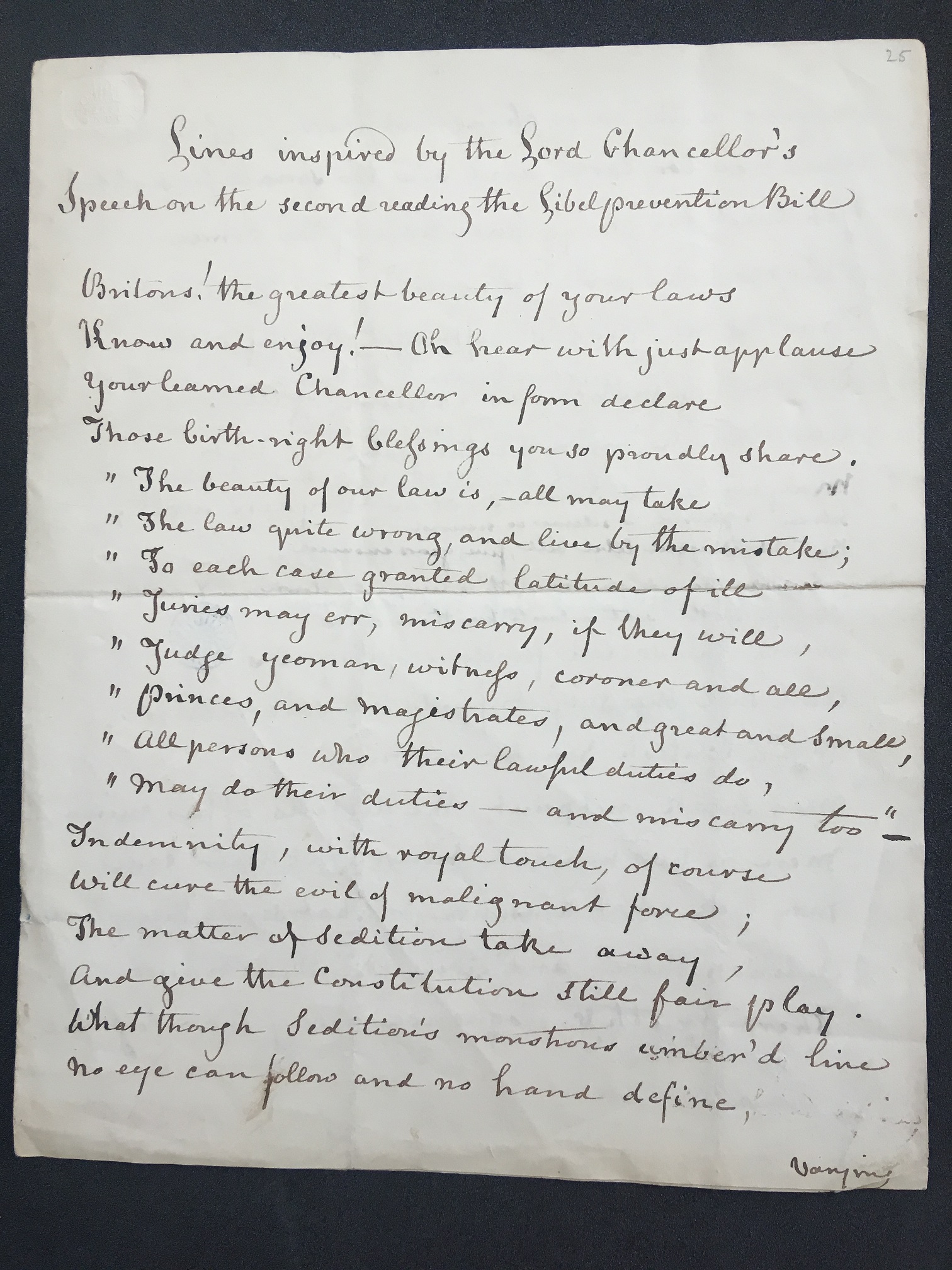

We should not overstate her interest in the events at Peterloo: in her letter to her Aunt Ruxton, written on 18 August (MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.56) she does not mention Peterloo at all [though perhaps the news had not reached the Edgeworths]. Yet, in several letters we find Maria and her family commenting on political stories in the newspaper whilst her sister Fanny’s (almost indecipherable) diary from our May blog, evidences the almost daily reading of parliamentary debates.

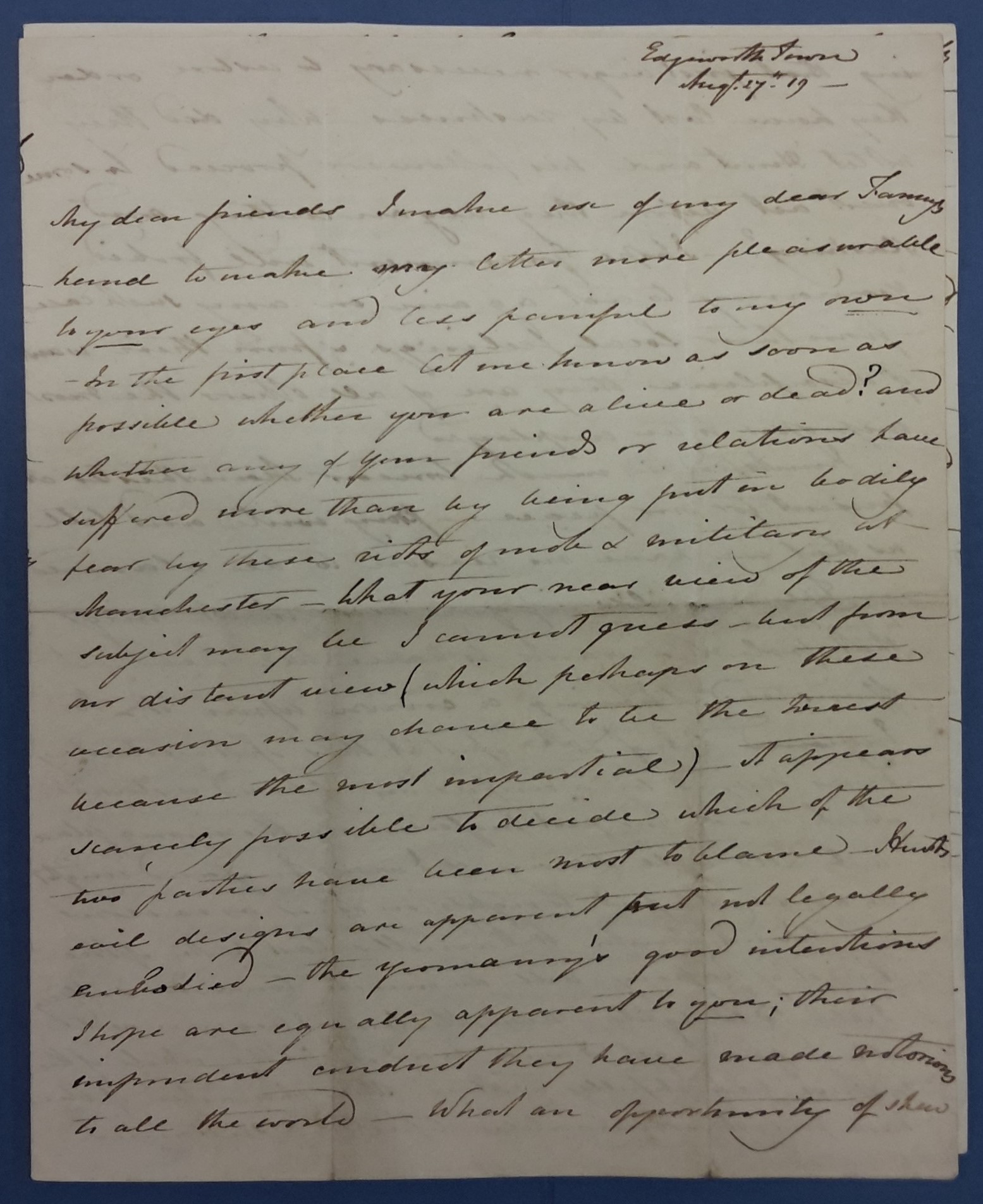

But the Edgeworth archive and Maria’s novels reveal more than just passing epistolary musings and fictional depictions of revolt and reform. Amongst the papers in the Bodleian, we find a manuscript copy of a poem entitled ‘Lines inspired by the Lord Chancellor’s Speech on the second reading [of] the Libel prevention Bill’ (MS. Eng. misc. c. 898, fols.25-6), apparently a ‘surplus copy’ of those circulated to members in Parliament. The Libel prevention bill was one of a series of measures (known as the Six Acts) Parliament passed in response to Peterloo, which hindered rather than furthered reform and focussed on curbing the rights of people, rather than – as Maria hoped – reforming the Yeomanry.

The ‘Lines…’ comment on the irony of Parliament attempting to curb the freedom of the press whilst benefitting from parliamentary privilege – that is, the legal immunity from prosecution offered to members of parliament which enabled them to speak freely in order to fulfil their duties. One consequence, however, was that they might make libellous claims without fear of legal challenge, whilst ordinary citizens were subject to increased scrutiny:

‘For still a British Senator we find

May speak (not print) the dictates of his mind,

Men in two honored houses at their ease

May talk what nonsense, or what sense they please,

Sedition there, and Libel, lose their name

There Truth & eloquence may lead to Fame!’

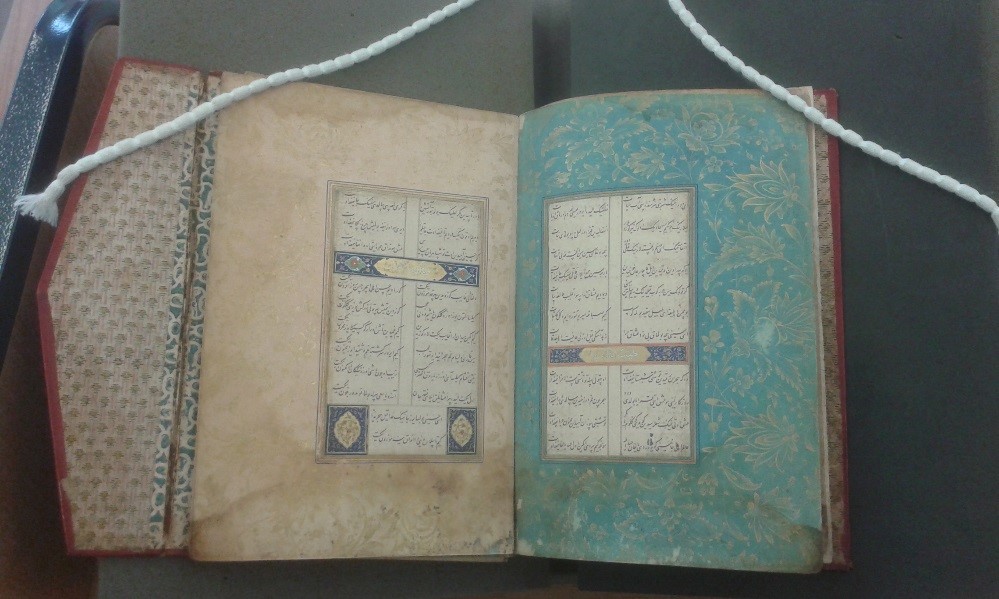

‘Lines inspired by the Lord Chancellor’s Speech on the second reading [of] the Libel prevention Bill’ (MS. Eng. misc. c. 898, fols.25-6)

‘Lines inspired by the Lord Chancellor’s Speech on the second reading [of] the Libel prevention Bill’ (MS. Eng. misc. c. 898, fols.25-6)

Transcription of MS. Eng. misc. c. 898 fols.25r-26v

Parliamentary privilege was an ancient custom. But, by the nineteenth century it had taken on a new dimension. Parliamentary speech had become subject to increasing coverage and scrutiny in the newspapers although the newspapers could not (and still cannot) print anything potentially libellous said in the chamber. Nevertheless, parliamentary speeches had been turned into theatre by great orators such as Edmund Burke (1729-1727) and Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816) in the previous century, with newspapers the platform for parliamentarians to achieve new kinds of ‘Fame’ – even if that ‘Fame’ was built on shaky foundations.

Maria Edgeworth’s politics are reformist rather than revolutionary and she consistently represented reform as a means of averting the suffering and violence attendant on outright rebellion. Edgeworth’s story ‘The Grateful Negro’ (written 1802 and published 1804 – one of 11 in Popular Tales) was a reformist take on the abolition debates. A fictional account of the 1760 slave rebellion in Jamaica, the story makes the case that sympathy and care for slaves would prevent violent rebellion and hence be to the economic and ethical advantage of the colonial system. While Maria was critical of abusive and neglectful landlordism, as we see in the satire in Castle Rackrent (1800) and the sentiment of The Absentee (1812) concerning Anglo-Irish rule, she did not criticise the (colonial) system itself. So too, she takes a reformist approach to the issue of slavery – the Jamaican planter Mr Edwards concludes a benevolent exercise of slavery is the best way to sustain the system which supports his livelihood and reconciles his conscience. ‘The Grateful Negro’ was also as Elizabeth S. Kim explains, a vehicle for debating the rights and wrongs of a rebellion nearer to home – the Irish rebellion of 1798.

Our investigation of the letters has uncovered a reference hitherto undiscussed to an encounter with a black woman on Irish soil. While she makes no direct reference to Peterloo in her letter composed the day after the massacre of 18 August to her Aunt Ruxton, Maria provides a short note smuggled into the top right hand corner of a scrappy one page sheet; here she describes a meeting with one Mrs Blackall. Despite interest in Maria’s literary depictions of race, there has been little or no attention to this brief mention of her encountering a mixed-race woman on Irish soil. Maria records that:

‘We dined yesterday at Mrs Whitman where we met Captn & Mrs Blackall — who is 3/4th a negress—Black all indeed. Pray when does the Bishop arrive’

In the third edition of her novel Belinda (1810), Maria erased the suggestion found in the first two editions to a mixed-race marriage, such as the one she described in this letter. Edgeworth changed the name and the reference to the skin colour of Belinda’s white West Indian suitor, Mr Vincent, in her novel: Juba, the African servant who marries the white daughter of a tenant farmer, Lucy, becomes plain James Jackson. But as her encounter with the Blackalls demonstrates, interracial couples would later feature in the Edgeworths’ daily lives.

Maria consistently argued for reform to avert the violence and cruelty she thought resulted from both sides in systems of oppression, whether in Manchester, Jamaica or Ireland. However, there is some cruelty to modern ears in the laboured pun she elaborates in this brief sentence concerning Mrs Blackall, a woman of African descent.

Maria’s Letter to Aunt Ruxton (18 August 1819, MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.56)

Maria’s Letter to Aunt Ruxton (18 August 1819, MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.56)

Transcription of Maria’s Letter to Aunt Ruxton 18 August 1819 MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.56

The Edgeworth papers are full of such interpretive cruxes. They reveal to us not only strangeness and distance but surprising connections and unexpected moments of encounter.

Looking beyond the Edgeworth papers there are a number of events this year in and around Greater Manchester to commemorate Peterloo including ‘Making the News: Reading between the lines, from Peterloo to Meskel Square’ at the Portico Library, ‘From Waterloo to Peterloo’ at Gallery Oldham, and a public re-enactment in St Peter’s Square on 16 August 2019.

Ros Ballaster and Anna Louise Senkiw

References

Elizabeth S. Kim, ‘Maria Edgeworth’s The Grateful Negro: A Site for Rewriting Rebellion’, in

Eighteenth-Century Fiction, Volume 16, Number 1, October 2003, pp.103-126.

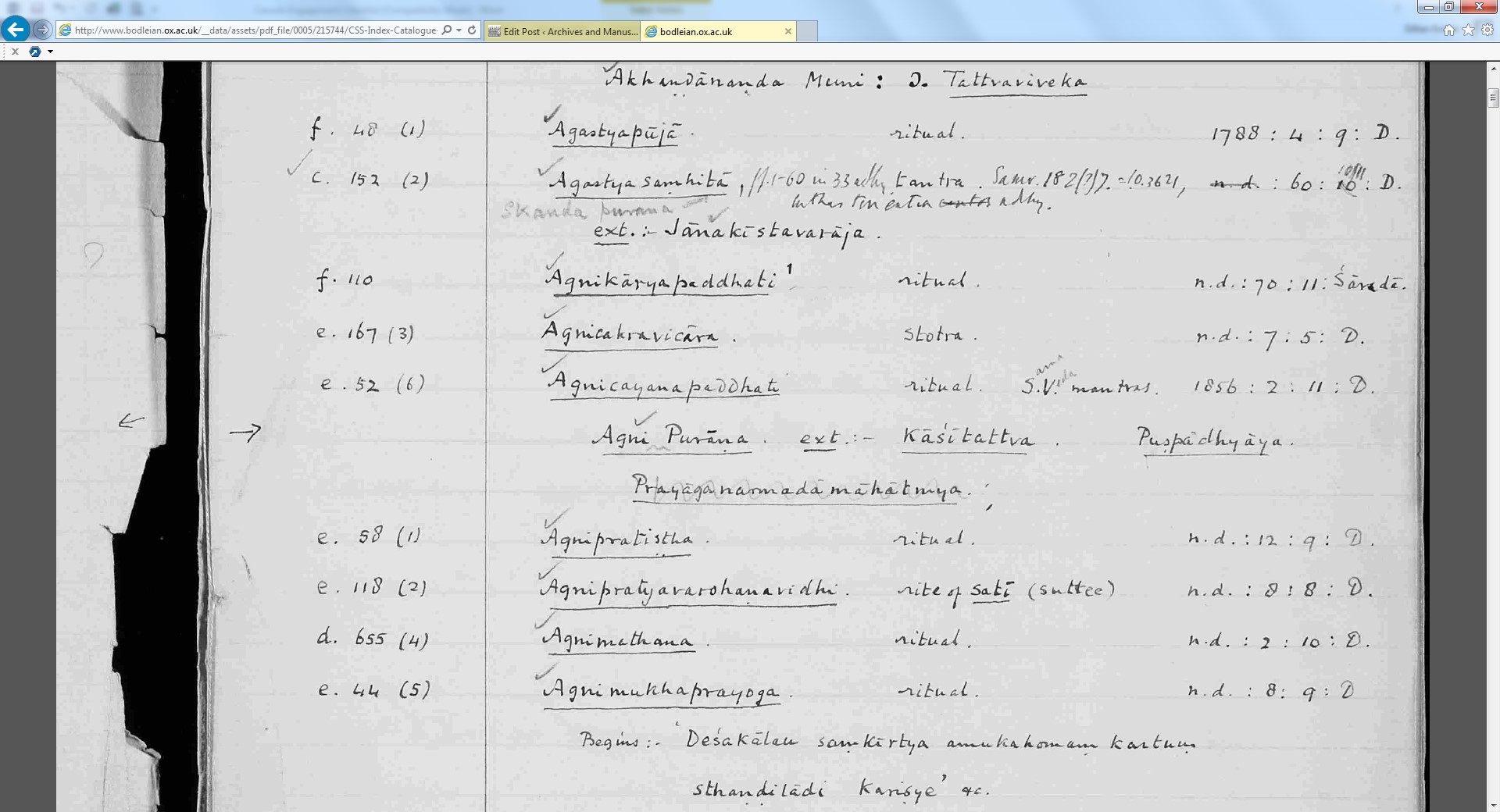

The site includes a general introduction to the archives held by the Oxford colleges, individual pages on most of the colleges (with further links to catalogues etc.) and links to associated archives in the City and University. There is also an FAQ page, a glossary of all those odd Oxford terms, and a bibliography. The site will be enhanced and updated regularly.

The site includes a general introduction to the archives held by the Oxford colleges, individual pages on most of the colleges (with further links to catalogues etc.) and links to associated archives in the City and University. There is also an FAQ page, a glossary of all those odd Oxford terms, and a bibliography. The site will be enhanced and updated regularly.

Our diarist was moving in quite elevated circles, and Mr Hare seems to have been the key figure in her entourage. This promising lead was reinforced by a stark entry in the diary:

Our diarist was moving in quite elevated circles, and Mr Hare seems to have been the key figure in her entourage. This promising lead was reinforced by a stark entry in the diary:

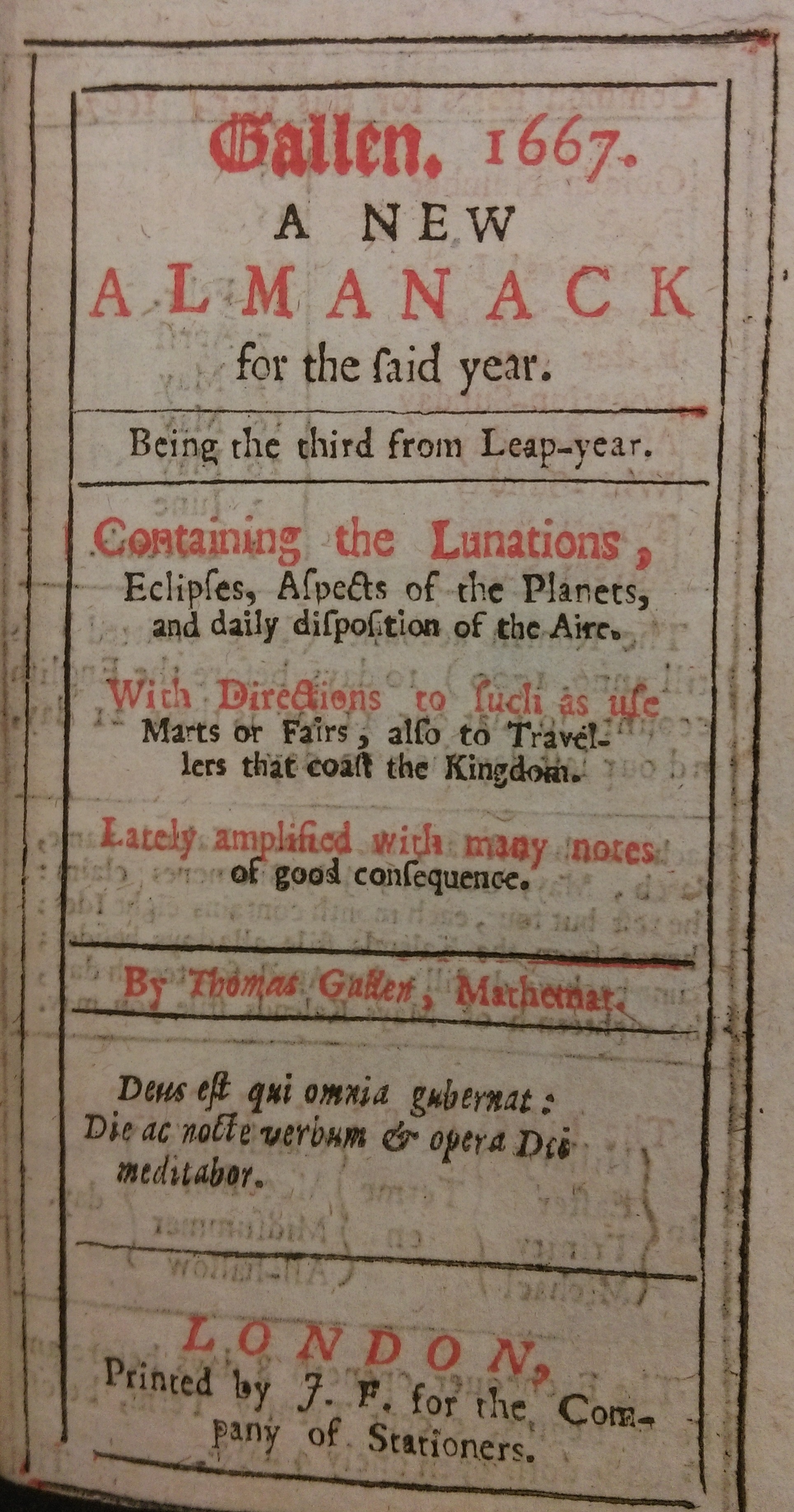

f a rare book (we have traced a handful of Gallen almanacs in the Bodleian, and none for 1667), has become a unique manuscript as it contains a diary of Jeffrey (or Jefferay) Boys of Betteshanger, Kent for the year 1667. The

f a rare book (we have traced a handful of Gallen almanacs in the Bodleian, and none for 1667), has become a unique manuscript as it contains a diary of Jeffrey (or Jefferay) Boys of Betteshanger, Kent for the year 1667. The