It’s often said that the first woman to receive an honorary degree from the University was Queen Mary. She received a Doctorate of Civil Law (DCL) by diploma on 11 March 1921. A degree by diploma is similar to an honorary degree, in that it’s conferred without the recipient having to study or sit any exams. The difference is that degrees by diploma are for royalty and heads of state only.

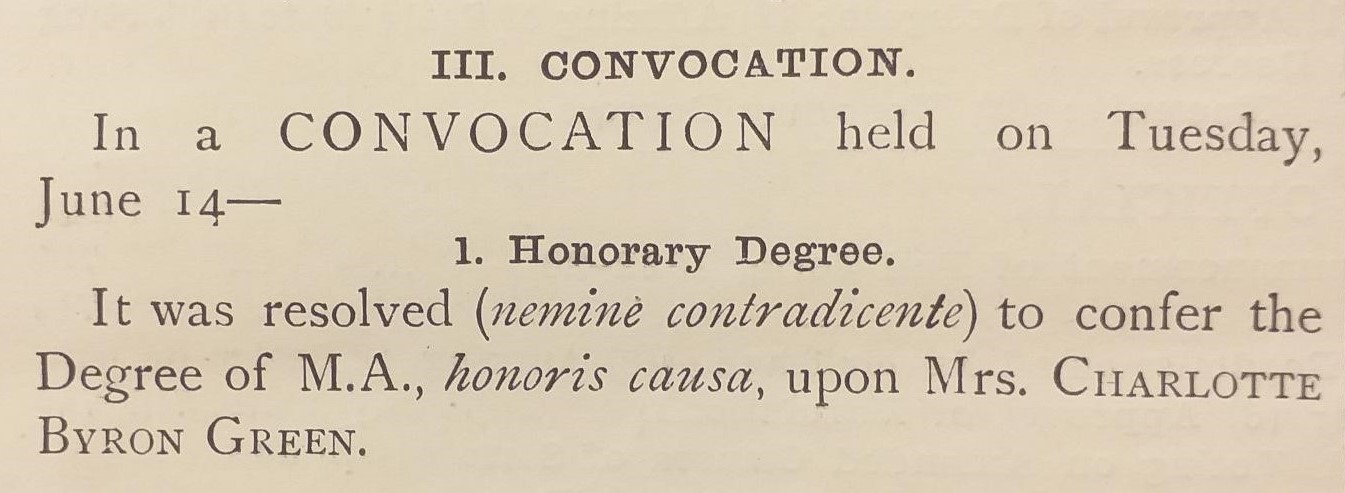

The first woman to receive an honorary degree proper was Charlotte Byron Green who received an honorary Master of Arts (MA) on 14 June 1921. Honoured for her work as a longstanding campaigner for women’s education in Oxford, Charlotte had been a founder member of the Association for the Education of Women (or AEW) which had promoted women’s education in Oxford since 1878. She had connections with Somerville and St Anne’s Colleges, as well as with the city of Oxford, having trained as a district nurse at the Radcliffe Infirmary.

Charlotte was shortly followed by the second female recipient, Elizabeth Wordsworth, former Principal of Lady Margaret Hall and founder of St Hugh’s College (both women-only colleges at that time) who received her honorary MA on 25 October 1921. She was also honoured for her work promoting women’s education in Oxford.

It’s interesting to note that neither Charlotte nor Elizabeth received their degrees at Encaenia, and both were awarded the lesser honorary degree of MA (rather that the doctorates usually conferred at Encaenia). The two ceremonies appear to have been held with very little fanfare and no documentation from either survives in the University Archives. The only record is the decision made on 30 May 1921 by Hebdomadal Council, the University’s executive body, to confer the degrees on Charlotte and Elizabeth.

Given their ground-breaking nature, it’s perhaps surprising that more was not made of these events at the time. Although the University was finally acknowledging the achievements of these women in their long fight for equal academic opportunity (both were elderly by this time: Charlotte, 78, and Elizabeth, 81), there was maybe an irony in honouring them for achieving something which the University had spent so many years resisting.

In the new few years Charlotte and Elizabeth were followed by more eminent women receiving honorary MAs, nearly all of whom were honoured as campaigners for women’s education. The first honorary doctorate was not conferred on a woman until 1925 when Harvard astronomer, Annie Jump Cannon, received an honorary Doctor of Science (DSc).

![Painting of Princess Dagmar of Denmark wearing a crinoline in the 1860s, by A. Hunæus, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons [https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32440689]](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2021/03/499px-Princess_Dagmar_of_Denmark_with_her_dog.jpg)

![Black and white portrait of Sir Stafford Cripps, c. 1947 [Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO)] [Creative Commons CCO 1.0]](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2021/04/518px-Stafford_Cripps_1947.jpg)