by Martin Holmes

Alfred Brendel Curator of Music, Bodleian Libraries

Fig. 1: Oil sketch by Carl Begas (1794-1854) of Mendelssohn aged 12, shortly before his flowing locks were cut off (MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn e. 5). The full portrait for which this study was made is sadly lost.

A major milestone in the ongoing music manuscript and archives cataloguing project has been reached with the conversion of the first two volumes of the printed catalogue of the Bodleian’s Mendelssohn collection (https://archives.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/7530). (The third volume is devoted to printed music so lies outside the scope of this project, but its contents are already included in the SOLO catalogue.)[1]

Given the importance of England to Mendelssohn’s career and his perhaps disproportionate prominence in and influence on the musical life of this country, it is not inappropriate that there should be a Mendelssohn archive here, in his almost-adopted homeland. However, the collection contains far more material than that relating specifically to his activities on this side of the English Channel.

The Library owes the existence of its Mendelssohn collection not to any direct relationship of the composer to the City of Oxford but to the fact that one of the composer’s grandsons, Paul Victor Mendelssohn Benecke (1868-1944) settled in Oxford in the 1890s, first as a student and later as a Fellow of Magdalen College. Paul took a great interest in the family treasures he had inherited from his mother and set about adding to his collection by persuading his cousins to part with other items, including the series of 27 volumes (known as the ‘Green Books’) containing practically all the correspondence received by the composer from the age of 12. (The extremely fragile ‘Green Books’ are currently undergoing a programme of disbinding and conservation which it is hoped will help facilitate a future digitization project.)

Fig. 2: A letter from Goethe to the 16-year-old Mendelssohn. The composer had first visited Goethe when he was only 12 and he made a deep impression on the elderly poet. (MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn b. 4 (13).

In Oxford, Paul Benecke renewed an acquaintance with Margaret (‘Marga’) Deneke (no relation despite the similarity of name), whose family had been neighbours of the Beneckes in Camberwell. From 1916, Marga Deneke lived with her sister at ‘Gunfield’, a large house in Norham Gardens where they held frequent concerts and musical soirées which were well-known on the Oxford music scene, attracting occasional visits from the likes of Albert Schweitzer, Paul Wittgenstein and Albert Einstein, as well as more local musicians.

Eventually, following Marga’s own purchase of a Mendelssohn manuscript, Paul decided to pass on his entire collection to her and it was moved to her North Oxford home. After Paul’s death in 1944, Marga set about accumulating whatever other Mendelssohniana she could find, encouraging other descendants of the composer to sell or give items to her growing collection. Additions at this time included the remarkable series of sketchbooks, acquired from the Swiss branch of the family, which demonstrate the composer’s prodigious artistic talent and provide a record of his frequent travels. Much of the collection was deposited in the Bodleian in the 1950s and 60s for safe keeping and, following Marga’s death in 1969 and that of her sister in 1973, the collection passed formally into the ownership of the Library which has since tried to augment it further as opportunity and funds allow.

Fig. 3: The Pass of Killicrankie as sketched by Mendelssohn on his famous Scottish tour of 1829 (MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn d. 2, fol. 19). You can follow Mendelssohn’s travels virtually at https://www.mendelssohninscotland.com/ where many of the Scottish sketches are reproduced.

Most of Mendelssohn’s completed music manuscripts were given to the Royal Library in Berlin in 1878 (now the Staatsbibliothek (SBPK)). Major music manuscripts are therefore generally lacking from the Oxford collection. Instead, it is particularly rich in biographical material: in addition to the correspondence and the sketchbooks, the other papers in the collection reflect every aspect of the composer’s life, from his childhood to his death, and include documents such as his elementary school reports, early harmony exercises, diaries, account books, albums and a large portion of Mendelssohn’s personal library – even a couple of his conducting batons, his death mask and a lock of his hair. There certainly are music manuscripts in the collection, including both his first and last compositions, but most are sketches or early drafts which, to some, are arguably more interesting than the finished fair copies. Other members of the family are also represented in the collection, notably Felix’s talented sister Fanny Hensel and his wife Cécile.

Fig. 4: The opening bars of the Hebrides Overture, probably Mendelssohn’s most famous work, inspired by his Scottish tour of 1829. Final autograph draft score, purchased in 2002 with funds provided by the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Friends of the Bodleian and individual donors. (MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn d. 71, fol. 1)

As one of the Library’s most important music collections, the Deneke-Mendelssohn archive is in high demand, not only from music scholars but also from historians researching the many people who corresponded with Mendelssohn and those interested in the Romantic movement more broadly. As Mendelssohn’s talent as an artist becomes better known, the sketchbooks and watercolours are generating considerable interest and, with the recent publication of the first real attempt at a comprehensive list of Mendelssohn’s drawings and paintings{2}, that interest is likely to grow further. In addition to the artwork, other highlights of the collection include the autograph vocal score of Elijah, the Mendelssohns’ Honeymoon Diary, performing materials from the composer’s revival of Bach’s St Matthew Passion and the final autograph score of the Hebrides Overture (a more recent acquisition).

The catalogue now published online in Bodleian Archives & Manuscripts is based on the text of Margaret Crum’s printed catalogue of 1980 and 1983 but incorporates the large number of corrections and amendments made to the reading room copy over many years, principally by the former Music Librarian, Peter Ward Jones (himself a leading authority on Mendelssohn). Other updates have been made (as time has allowed), including descriptions of items acquired since the printed catalogues were published and references to more recent scholarship. It is hoped that the launch of the online catalogue will further raise awareness of the collection and make it easier for scholars and other musicians to discover and access the wealth of fascinating material it contains.

References:

[1] Catalogue of the Mendelssohn papers in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, vols. 1-2, compiled by Margaret Crum (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1980-1983); volume 3, compiled by Peter Ward Jones, was published in 1989.

[2] Ralf Wehner, ‘»Mit Deinen Rebusen machst Du uns doch alle zu Eseln«.Zu einigen Bilderrätseln von Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’, Mendelssohn-Studien, Bd. 20 (2017), pp. 111-126.

Fig. 5: Sketch of Pozzuoli, Naples (20 May 1831), showing Mendelssohn’s particular skill and love for drawing buildings and boats. He was less good at drawing people! (MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn d. 3, fol. 3)

Fig. 6: The Château de Chillon (23 Dec 1843). This tiny watercolour by Mendelssohn measures only a few centimetres across (MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn c. 49, fol. 97). Done from a pencil sketch at MS. M. Deneke Mendelssohn e. 1, fol. 4, made the previous year.

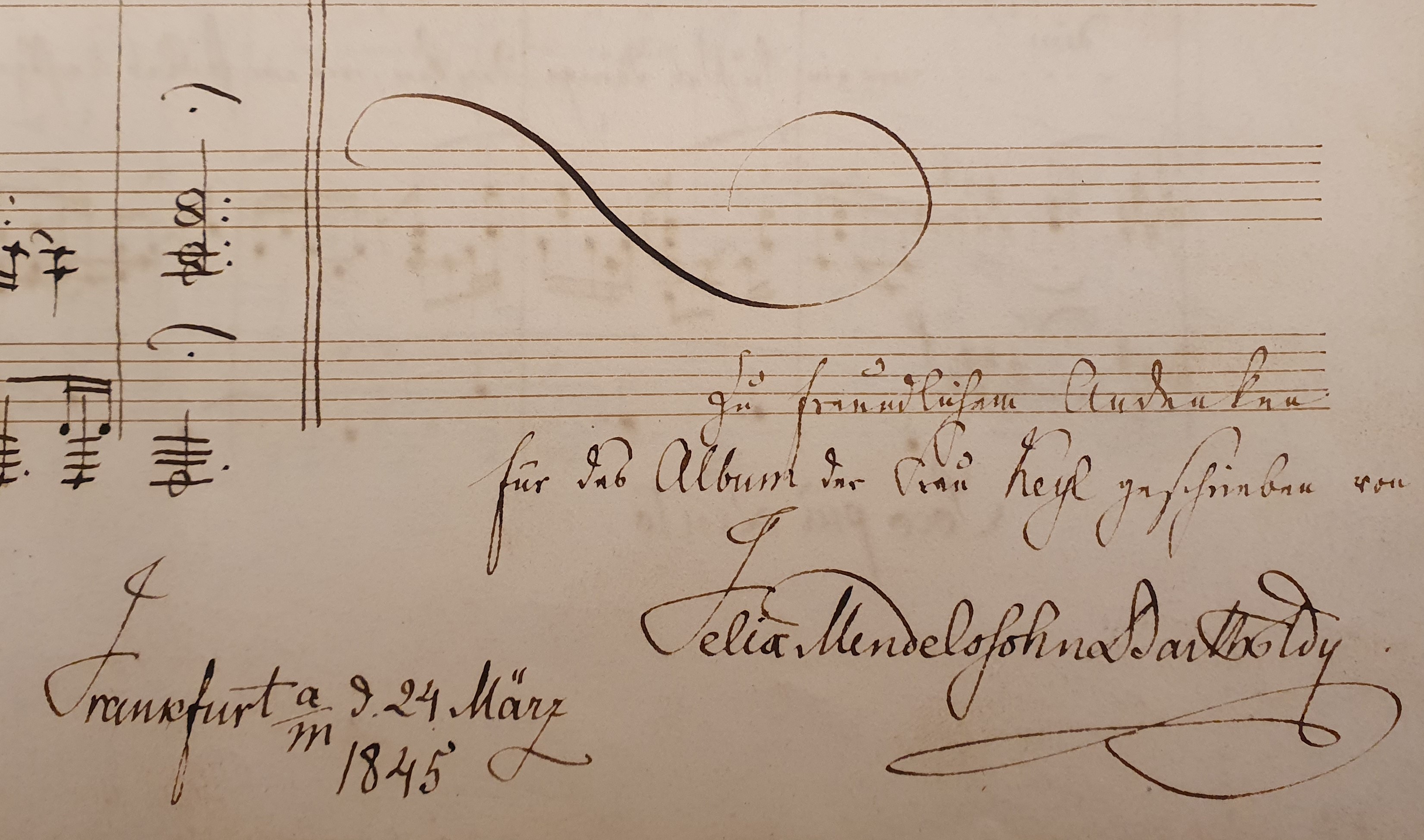

Fig. 7: A particularly fine example of Mendelssohn’s signature, appended to a presentation copy of his Schilflied, dated 24 March 1845 (MS. M. Deneke Menedelssohn c. 101)

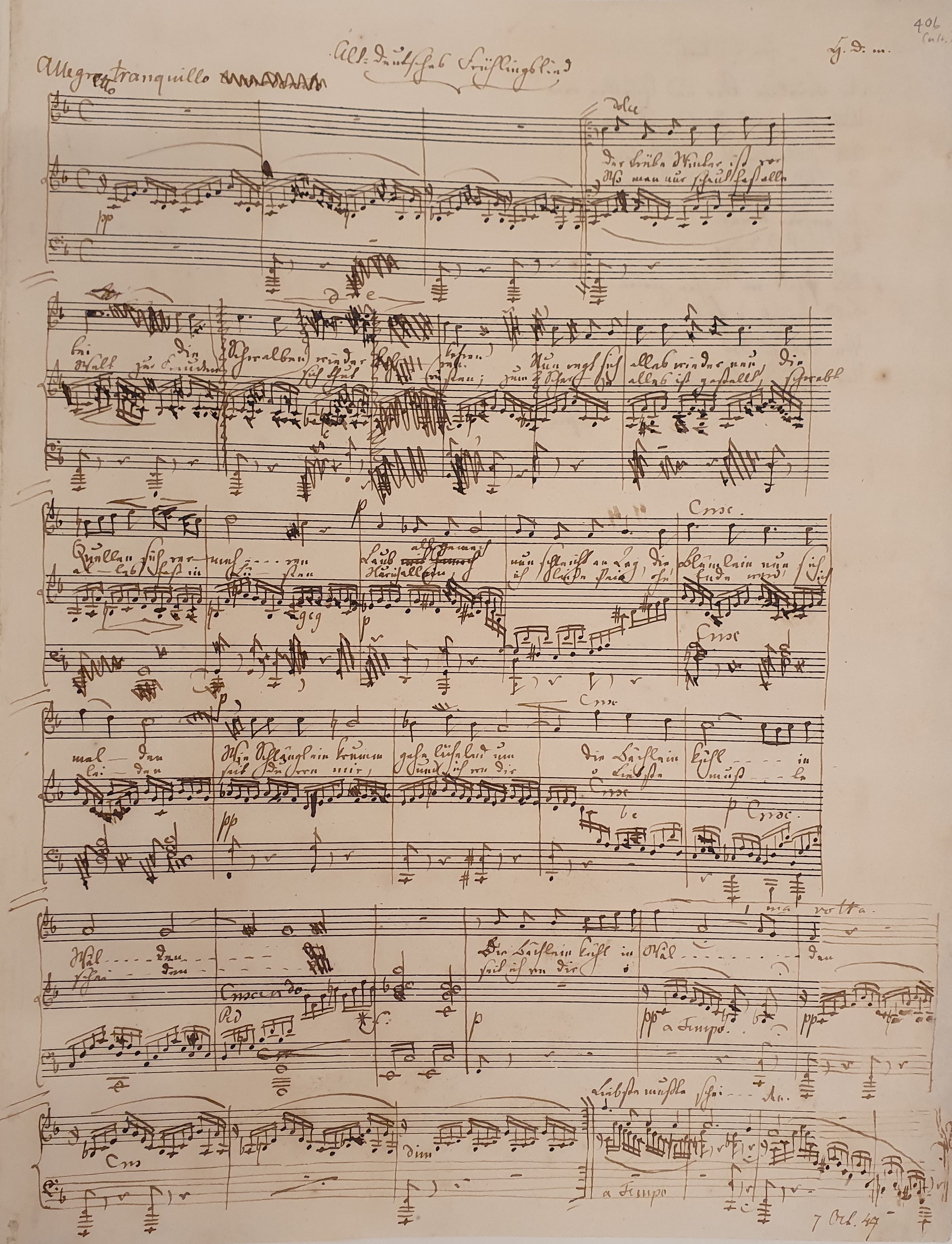

Fig. 8: Mendelssohn’s final composition, the Altdeutsches Frühlingslied (‘Old German Spring Song’), written on 7 October 1847. The text alludes to the death of his beloved sister Fanny earlier in the year. Combined with overwork, the shock of her sudden death had sapped him of his strength and he succumbed to his final illness just a few weeks later.