Between 1926 and 1939, the School Empire-Tour Committee, an offshoot of the Church of England Council of Empire Settlement, organised a series of Empire tours for British public school boys that started with a trip to Australia in 1926 [1], and ended with a tour of Canada in 1939. In between, these tours took groups of young men to South Africa, New Zealand, East Africa, the West Indies, and (twice) to India, and the family archive of the Earls of Clarendon in the Bodleian Library contains what might be a uniquely complete record of one of these India tours.

The Royal Commonwealth Society (RCS) collections at Cambridge University Library hold most of what survives of the School Empire-Tour Committee’s records since most were destroyed when the headquarters of the RCS, then known as the Royal Empire Society, was bombed in 1941. The surviving records include some minute books, reports, correspondence, lists of tours and their participants, and an album with group photographs – but little else, which makes the existence of this small collection in the Clarendon archive a particular treasure.

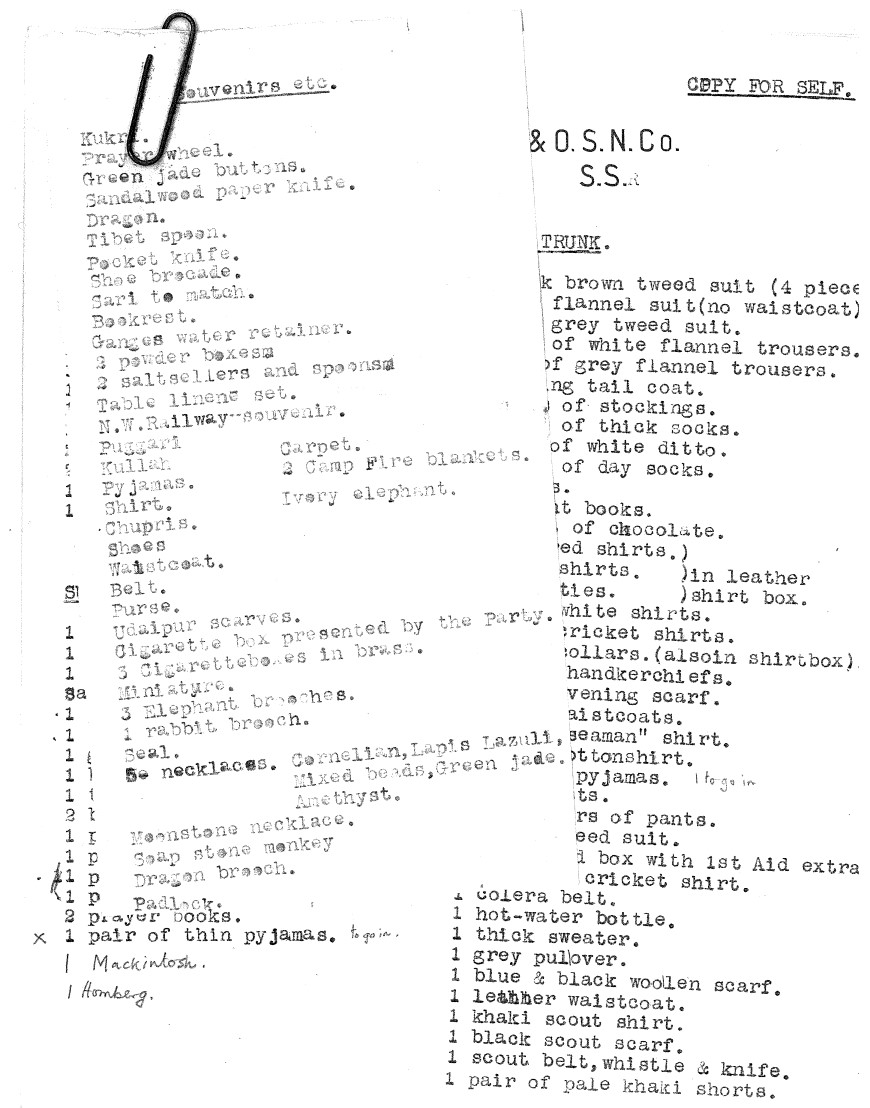

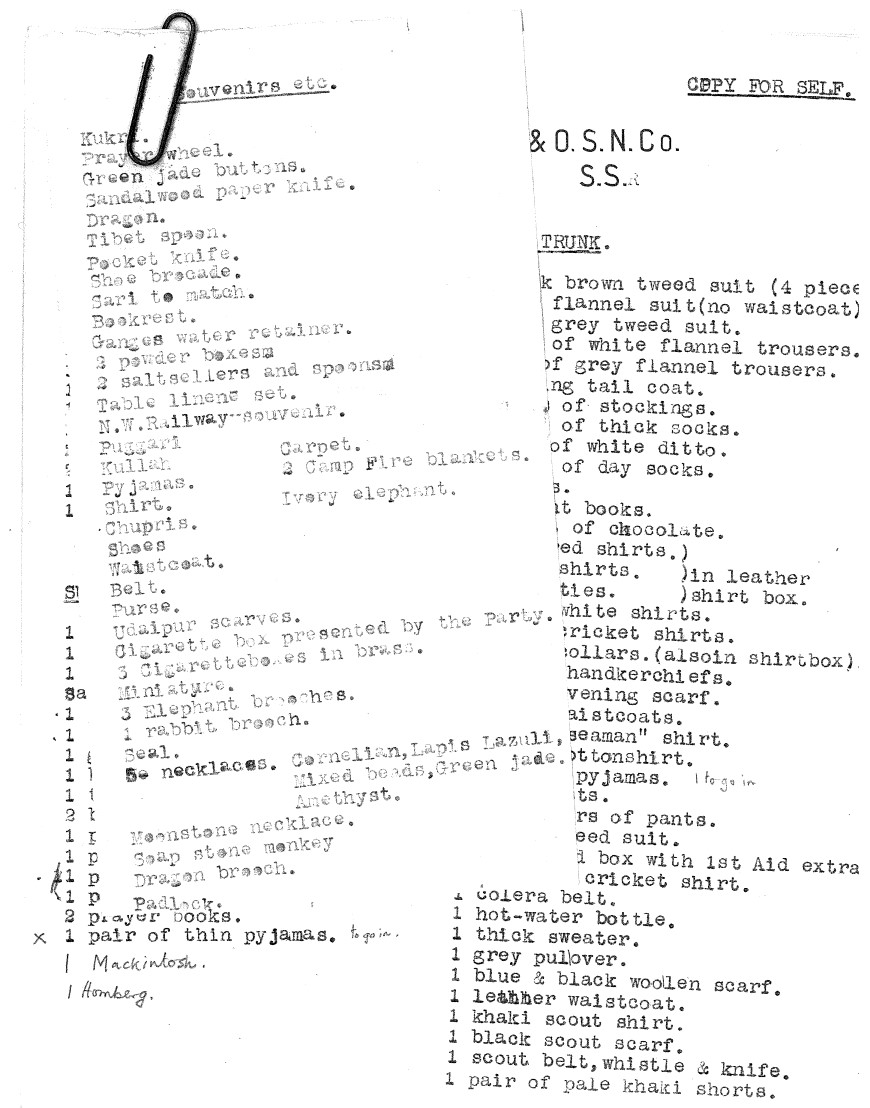

Lord Hyde’s list of souvenirs to buy in India, overlaying his packing list, 1929 [click to enlarge]

In the winter of 1929-1930 Lord Hyde, the 23 year-old son and heir of the 6th Earl of Clarendon, acted as the unpaid advance agent for the Committee’s first tour of India, for 27 mainly English public school boys (25 English and 2 from Edinburgh and Duns in Scotland)

[2]. The Clarendon archive includes Lord Hyde’s tour memorabilia, photographs, his typed tour report with many useful suggestions for future tours (not least ‘One great thing to avoid…is an early start; the boys sleep like logs’), and even a list of clothes to pack, including ‘trousers, grey flannel’ and ‘ties, black evening’

[3].

It also includes a letter from the Hon. Margaret Mary Best, the Honorary Secretary and beating heart of the School Empire-Tour Committee, commenting in enthusiastic red ink that ‘SOME OF THE DIARIES ARE VERY INTERESTING’, a tantalising reference to what was likely a pile of travel diaries from the boys who participated, subsequently lost in the bombing. She also thanks Lord Hyde for arranging lectures for the party to help them understand what they were seeing, and the papers include notes on Hindu gods and a short ‘Outline of the History of Hindustan, 1000-1761’ (typed on P&O writing paper, so possibly a last-minute research effort, or a relic of lectures offered on the long voyage) as well as numerous printed guides, mainly from the Archaeological Department of H.E.H. The Nizam’s Government, Hyderabad.

The ten week tour was both extensive and exclusive, announced in advance in the newspapers, and well supported by local government officials. Included in the collection is a seating plan for a 9 December 1929 luncheon for the boys at Government House in Calcutta and a souvenir sports programme [4] for an event celebrating the arrival of Maharani Cinakuraja Saheb Scindia, president of the council of regency of the princely state of Gwalior (now in Madhya Pradesh), at Baroda (now Vadodara in Gujarat) on Saturday 1st February, 1930. The sports programme featured a variety of sports, including an elephant race and multiple types of wrestling, with the names of the wrestlers also listed.

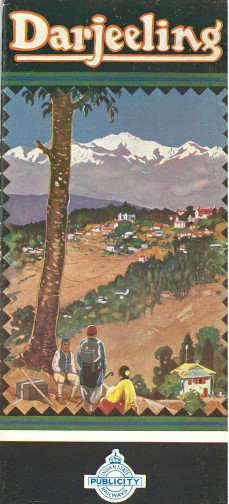

An information pamphlet about Darjeeling, from the Indian State Railways publicity department, c. 1929

Aside from official events, the group, who travelled for much of their journey on a special passenger train with ‘Empire School Tour’ emblazoned on the side, followed a busy itinerary drawn up by the India Office, staying at private homes, schools, colleges and state guest houses along the way. The official itinerary is not included in the papers but the tour took in some of the tourist highlights of central and northern India, right up to the Himalayas and the frontier with Afghanistan. Lord Hyde kept picture postcards of the Ellora Caves and Daulatabad Fort (in Maharashtra, not too far from Mumbai), as well as Darjeeling in the far north of India, plus a guidebook to the holy city of Varanasi, then called Benares (and, intriguingly, three postcards of Ceylon, although it is unlikely that they sailed to Sri Lanka) as well as colourful timetables and memorabilia produced for tourists by Indian State Railways. Lord Hyde also took some highly evocative photographs, with shots of landscapes and temples and forts (and, of course, the Taj Mahal) as well as group photos of young men in shorts and sun helmets and numerous snaps of the animals they hunted along the way. (Hyde was particularly keen that shooting should be allowed on all future tours: ‘I am quite convinced that without the shooting, the tour might have been regarded as purely an educational one and therefore rather a drudgery’.) [5]

The stated reason for these tours was to interest the boys in the country ‘with a view to their settling in the country’, with the implication that they were being introduced to the dominions that they might administer one day, and indeed one of the boys’ activities was to stay with District Officers in the Punjab to see how the District was managed [6]. Hyde himself came from a family with a long history in the British government and imperial administration. His father, the 6th Earl of Clarendon, was Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs and Chairman of the Overseas Settlement Committee from 1925-1926, and kept a keen eye on the inaugural School Empire Tour to Australia. In December 1929, as Lord Hyde and the boys were starting their India tour, the 6th Earl was selected to be the next Governor General of South Africa. Lord Hyde himself, however, never reached those heights. He died in a shooting accident in South Africa on 27 April 1935, aged 28.

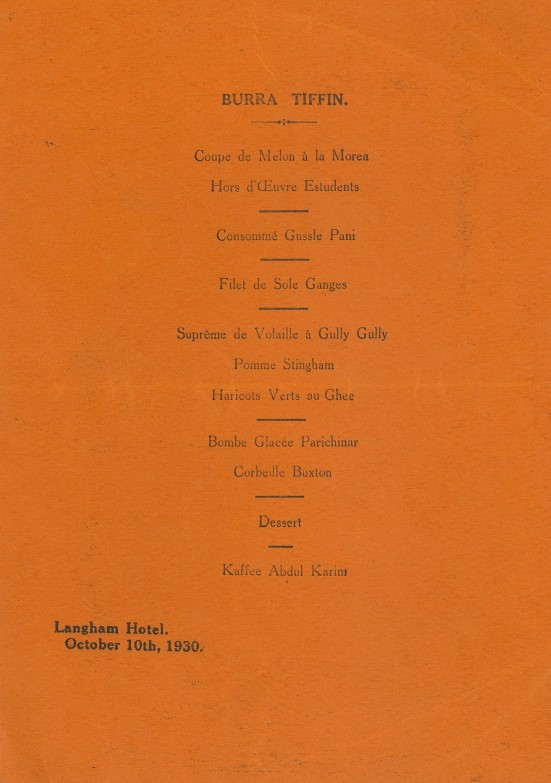

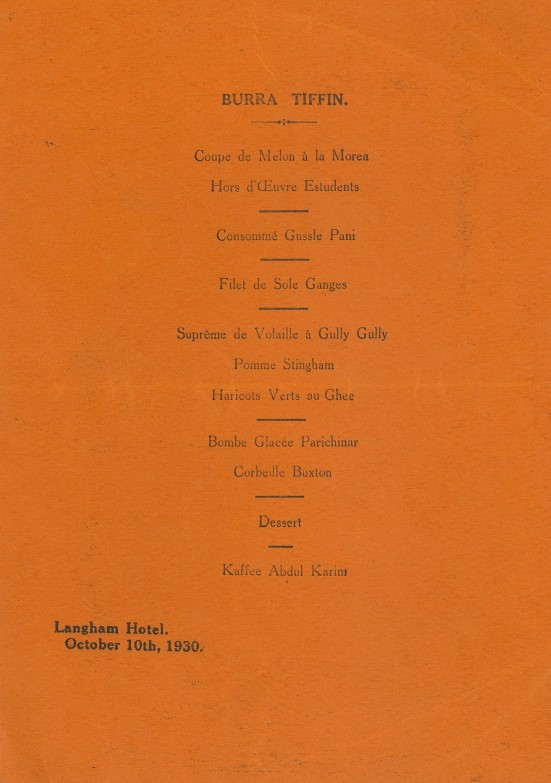

A strange, Indian-inspired menu from the Langham Hotel, 10 Oct 1930, featuring ‘Filet de Sole Ganges’ and ‘Haricots Verts au Ghee’, perhaps from a tour reunion meal [click to enlarge]

[1] The director of the first Australia tour, Rev. G.H. Woolley, V.C., M.C., wrote about it in his autobiography Sometimes A Soldier in 1963.

[2] ‘Public school’ means, confusingly enough, an elite private school. The Duns boy, and top of the alphabetical list of tour participants, was J.S. Arbuthnot, of Wedderburn Castle. He was then at Eton but was better known latterly as the Conservative M.P. Major Sir John Sinclair-Wemyss Arbuthnot (1912-1992).

[3] As well as a list of Hyde’s baggage, including ‘1 bag of golf clubs’ and ‘1 cinematograph camera in black case’. Sadly no film survives.

[4] The programme is written in Marathi, with thanks to Emma Mathieson, the Bodleian’s Modern South Asian Studies Librarian, for the translation.

[5] A post-tour letter to Hyde from Dr. M.J. Rendall, the Chairman of the School Empire-Tour Committee, suggests that ‘Drink’ [of some sort] was a problem on the tour, and that the ‘experience of this Tour may lead us to modify our instructions’. Lord Hyde was also clear that he wanted the boys to be better selected for future tours, so it wasn’t an entirely happy holiday. (This was also true of the original Australia tour: one boy had to be sent home early for joy-riding and crashing a £1000 car [Simpson, D (ed.) (1978), ‘The spirit of a lion and the appetite of a robin: Margaret Best and the School Empire Tours’, The Royal Commonwealth Society, Library Notes, New Series no. 226, p.2.])

[6] Although, as Hyde points out, if this was made explicit in India ‘I very much doubt if you would get any co-operation with the Indian schools, for their great object seems to be Indianisation’ and so broadening minds and promoting mutual sympathy was given as the justification instead, although Hyde was sceptical that sympathy had been achieved on either side.

These papers, of the Earls of Clarendon of the second creation, are currently being catalogued and will be available to readers in 2022.

![Oil painting of the HMS Resolution, a third-rate Royal Navy ship of the line, sailing in a gale, c. 1678 [by Willem van de Velde the Younger, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2021/04/512px-Van_de_Velde_Resolution_in_a_Gale.jpg)

![Painting of Princess Dagmar of Denmark wearing a crinoline in the 1860s, by A. Hunæus, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons [https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32440689]](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/archivesandmanuscripts/wp-content/uploads/sites/161/2021/03/499px-Princess_Dagmar_of_Denmark_with_her_dog.jpg)