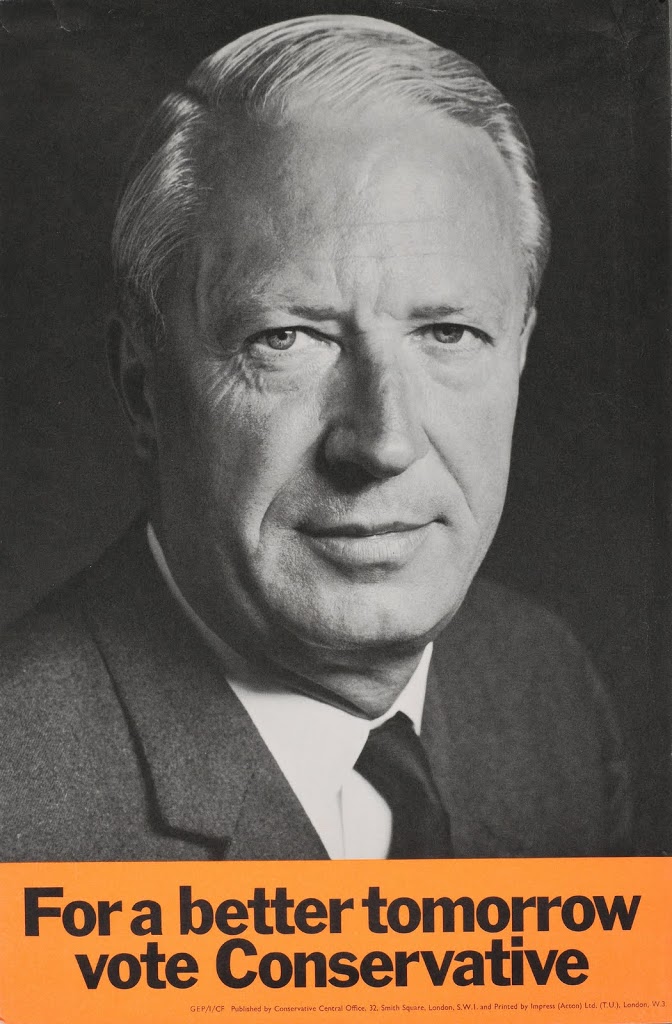

Britain’s two previous attempts to join the European Community – in 1963 and 1967 – had been humiliatingly rejected by the French. Two British prime ministers – Harold Macmillan and Harold Wilson – had both failed. Brought to power in the 1970 elections a new leader, Ted Heath, was determined to have a third try. But Heath faced two massive challenges: negotiating a place for Britain in Europe, and bringing the British public with him.

Like so much related to the history of Britain’s relationship with Europe, the story of Britain’s three attempts to join the EC are largely forgotten by the general public. Yet, as well as fundamentally changing the course of British post-war history, they can clearly inform current discussion of Britain’s place in Europe.

Getting in

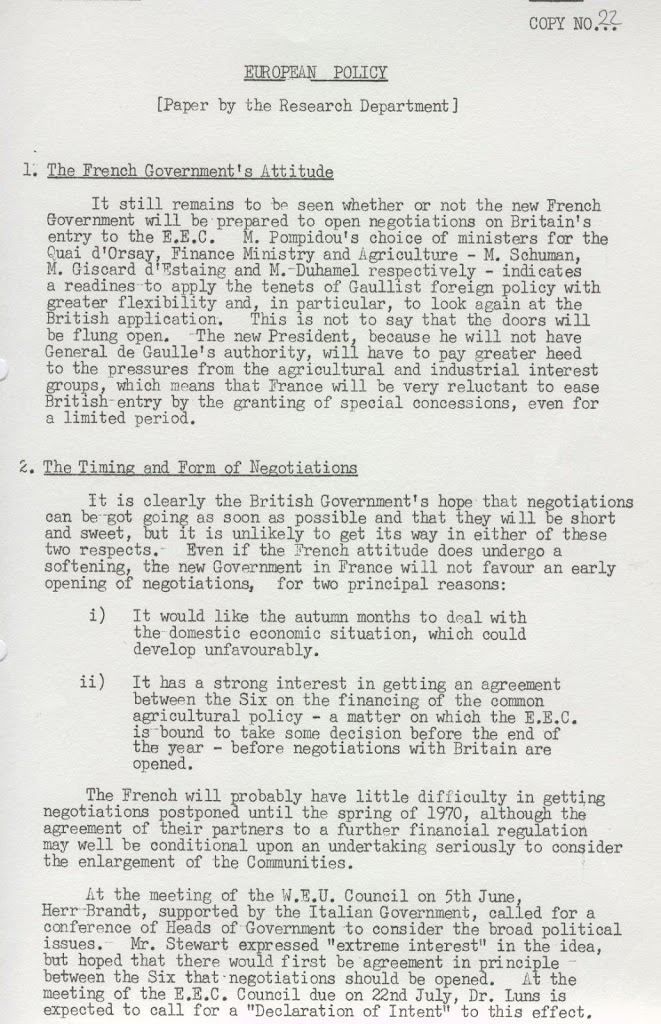

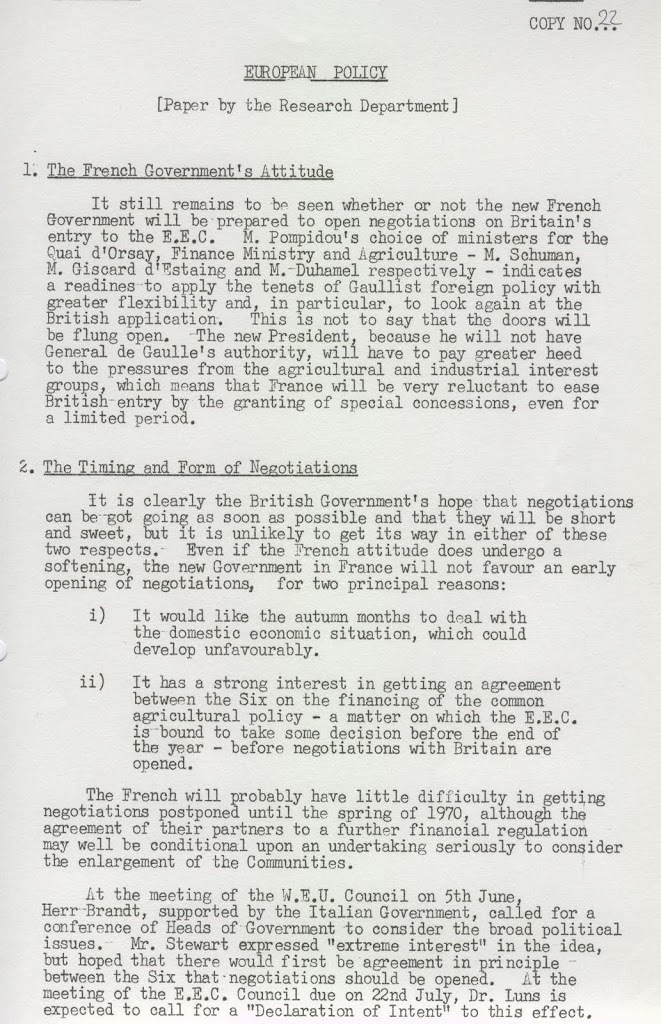

So, what had changed between 1967 and 1973? First, and perhaps most important, was the fall from power of General de Gaulle. De Gaulle, who had vetoed both British applications, was a victim of the 1968 student protest which forced him from the office he had held for a decade; in his place, the new president Georges Pompidou was considerably more sympathetic.

Brought to power in the 1970 general election, the Conservative government of Ted Heath decided that the time was right to revive the application that had been left dormant in 1967 after the veto. For Heath, the domestic pressures for Britain to enter the EC were just as powerful as they had been for Wilson. The lack of export markets for British industry was becoming an ever-greater problem and hastened the decline of British living standards. In 1945, Britons had been 90 percent better off than citizens of ‘the Six’; by 1969, they were six percent poorer.

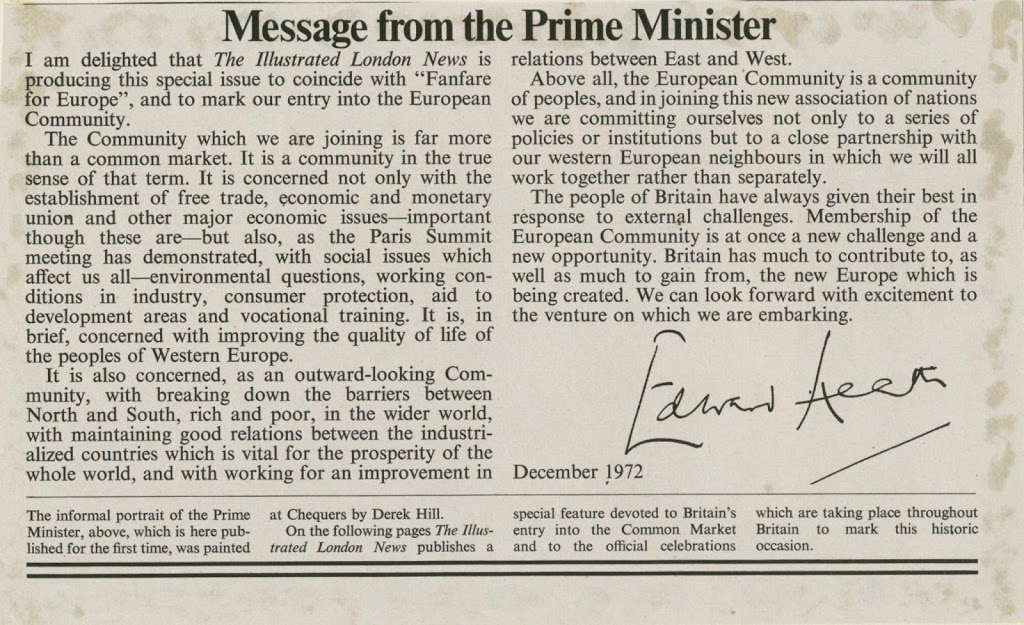

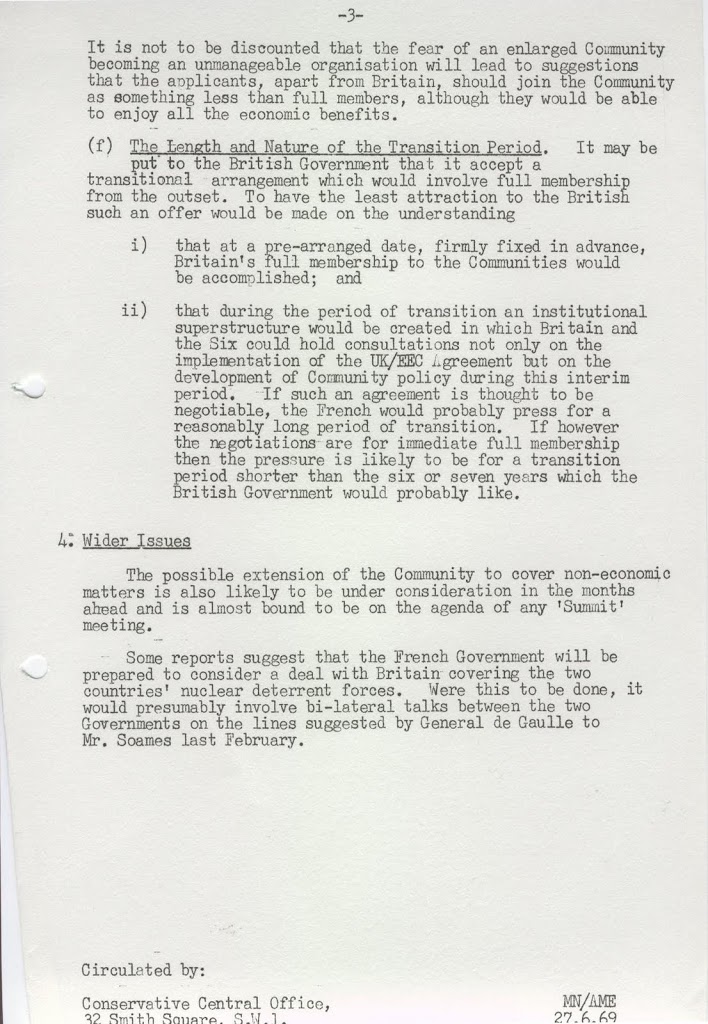

Negotiations opened in June 1970 alongside parallel negotiations with Britain’s traditional allies Ireland and Denmark. In January 1972, Heath finally signed the accession treaty in Brussels.

Party and people

The diplomatic negotiations were just the first obstacle that Heath faced; bringing Britain into Europe would also require the support of his party and the British electorate. This was a challenge that faced the Conservative Whips as they tried to make sure that enough MPs would vote with the government to pass the European Communities Act – the piece of legislation that was finalise the negotiations. It is on this aspect that many of the papers held by the Conservative Party Archives at the Bodleian focus.

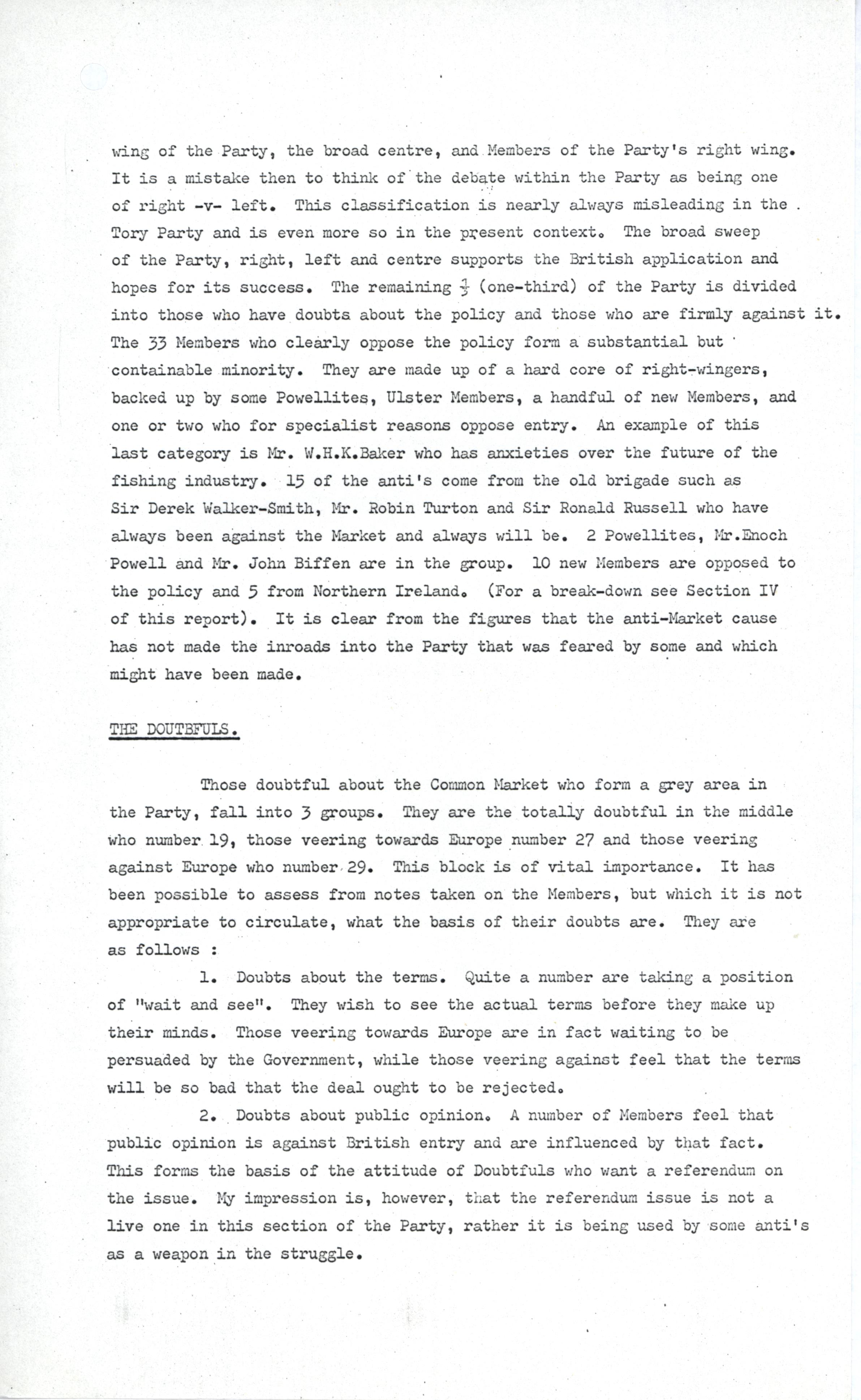

The Conservative Party, which had stood on a pro-European platform since Macmillan, clearly had a parliamentary mandate if only its MPs could be brought on-side. Looking at the Conservative Party’s 326 MPs in January 1971, the Whip’s Office was not entirely happy with what they saw. At least 218 could be counted on to support the government’s position but 75 were ‘in doubt’ and 33 ‘against’. Although comparatively small in number, the 33 (not to mention the large in-doubt contingent) could stop the government getting the votes it needed to pass the bill, especially considering the divided and disorganised state of Labour. The judgement on the 33 was pretty damning: ‘a hard core of right-wingers, backed up by some Powellites, Ulster members, a handful of new Members, and one or two who for specialist reasons oppose entry…[and] 15 of the anti’s come from the old brigade…who have always been against the Market and always will be.’ (CCO 20/32/28) By August 1971, when the terms of the negotiations had become clear, there was a big rallying to the government’s side. Just 21 were estimated to be implacably hostile and almost all of the undecideds had been won over. The Whips were also delighted to note that this rallying ‘has taken place in the House, in the Parliamentary Party; it has also taken place in the Conservative Party outside the House and amongst voters as a whole.’ (CCO 20/32/28)

CCO 20/32/28: ‘Third Report and Analysis on the State of the Party on Common Market Issue. August 1, 1971’.

Some voters writing into the party expressed their concerns whilst others wrote in support. Ultimately, however, the issue remained unsolved and the public divided. With the Labour Party also ambivalent towards Europe (a radical change of direction), confrontation was inevitable. In 1974, new elections brought Labour back to power with the promise that continued British membership of the EC would be decided by referendum. The result – a surprise 60 percent majority in favour of staying – guaranteed Britain’s role as a major player in European integration for almost half a century.

Guy Bud