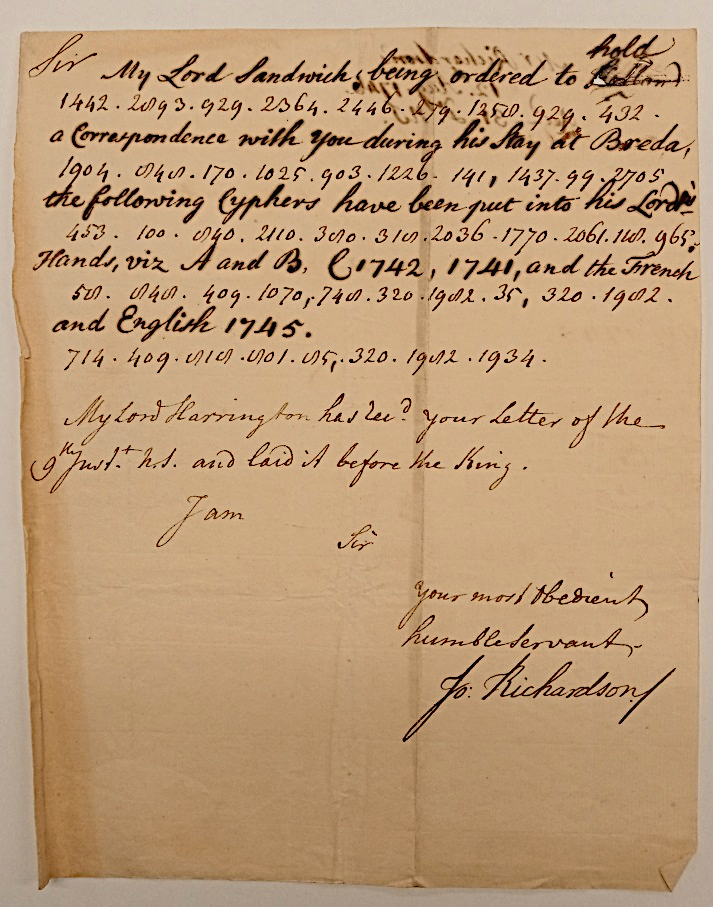

Deciphered diplomatic code in a letter to Thomas Villiers, later 1st Earl of Clarendon, 12 Aug 1746 [click to enlarge]

Decades after this letter was sent, Villiers revived an extinct title and became the 1st Earl of Clarendon (2nd creation) but in August 1746 he was the Hon. Thomas Villiers, second son of the Earl of Jersey, and working in Berlin as Britain’s envoy to the court of Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia, following a succession of diplomatic positions with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Electorate of Saxony and the Archduchy of Austria.

Frederick the Great liked Villiers enough to, many years later, give him a special grant to use the Prussian eagle on the Villiers family coat of arms but Horace Walpole, the writer, historian, and Whig politician thought that Frederick liked Villiers mainly because Frederick was wary of genuinely capable men: ‘[Villiers] has,’ Walpole wrote, ‘been very much gazetted, and had his letters to the king of Prussia printed, but he is a very silly fellow’ (Walpole, Corr., 20.17).

Whatever Thomas Villiers’ qualities as a diplomat, this coded letter shows something of his everyday work and the importance of confidentiality in the diplomatic service. They were right to be cautious. The ‘My Lord Sandwich’ the letter refers to, who is currently in Breda in the Netherlands, is the 4th Earl of Sandwich (the very man the sandwich is named after) who, at the Congress of Breda, apparently employed the British secret service to intercept and read French secret correspondence. This move helped Britain to diplomatically outmanoeuvre the French at the Congress, which were the peace talks to end the ruinous War of Austrian Succession.

This letter to Villiers is most interesting because it shows not just a number-based cipher, but the deciphered plain text. And although the letter itself doesn’t reveal any thrilling state secrets, it does show the essential exchange of keys so that sender and receiver can read the code.

And that, unfortunately, is about the limit of my understanding of cryptography. If there are any cryptographers reading, feel free to drop into the comments!

These papers, of the Earls of Clarendon of the second creation, are currently being catalogued and will be available to readers in 2022.