‘I will not disguise from the House, as I have not attempted to disguise from the country, the deep disappointment of the Government and, I think, of the whole nation, at the turn of events. […] If the European vision has been obscured, it has not been by a minor obstruction on one side or the other. It was brought to an end by a dramatic, if somewhat brutal, stroke of policy.’ ( HC Deb. 11 Feb 1963, vol. 671, fols. 943-1072.)

Speaking at a parliamentary debate in February 1963 shortly after Charles de Gaulle’s veto of British membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), it is perhaps easy to understand why Harold Macmillan was quite so bitter. After close to five years of negotiation, British hopes of joining the European Union’s antecedent had just been crushed – publicly – by a former ally, President Charles de Gaulle.

Britain, the Commonwealth, and Europe

Succeeding Anthony Eden as Prime Minister in 1957, Macmillan’s six years in power spanned a period of almost unprecedented change in Britain’s geopolitical status. The Suez Crisis of 1956, which had brought down the Eden government, demonstrated to the world that Britain was no longer a superpower in comparison to the United States or Soviet Union. No longer a major imperial power or, at least, no longer the major imperial power it had been twenty years before, the country was caught in a kind of malaise. The result was a difficult period of soul-searching about where Britain’s future should lie.

By the late 1950s, Britain’s economy was also encountering problems. Although Britain remained a rich country – richer, per capita, than most of continental Europe – the disparity between the levels of economic growth in Britain and the rest of Europe were becoming increasingly obvious. In order to keep in business, British industry needed ever-increasing overseas markets for its products.

Against this difficult backdrop, Britain was caught between two centres of gravity. One the one hand, the Commonwealth pulled the country towards its traditional export markets in the former colonies. Although very informal and disorganised, the Commonwealth – and especially the ‘White Dominions’ (notably Canada, Australia, and South Africa) – appeared to offer a way for the British to keep the economic benefits of empire as well as its sentimental attachments. On the other, attempts to form an economic union in Continental Europe were viewed with a mixture of scepticism and alarm.

In March 1957, six European countries (France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Italy) signed the Treaty of Rome, paving the way for a supra-national organisation intended to facilitate trade and political cooperation between the member-states. Macmillan faced a dilemma. Although not totally incompatible, Britain could not move towards both the Commonwealth and the EEC at the same time.

A difficult decision

The Macmillan archives on deposit at the Bodleian provide a fascinating snapshot of the difficulties of the decision, especially in the period immediately after the signing of the Treaty of Rome. They also show Macmillan’s attempt to play a difficult double game between what he termed ‘the practical’ and ‘the idealistic’ (Bodleian, MS. Macmillan dep. c.920, fol. 21). While he could certainly dress his actions in the ideology of Europeanism, he was also acutely aware of the dangers which a united Europe would create for a disengaged Britain.

MS. Macmillan dep. c. 920, fol. 21: Luncheon Speech for European Free Trade Area, 20 Feb 1957. Reproduced with kind permission of the Trustees of the Harold Macmillan Book Trust.

In a speech written for the European Movement Industrial Conference in February 1958, Macmillan wrote that he saw Free Trade as an ideological glue to cement unity within the Continent:

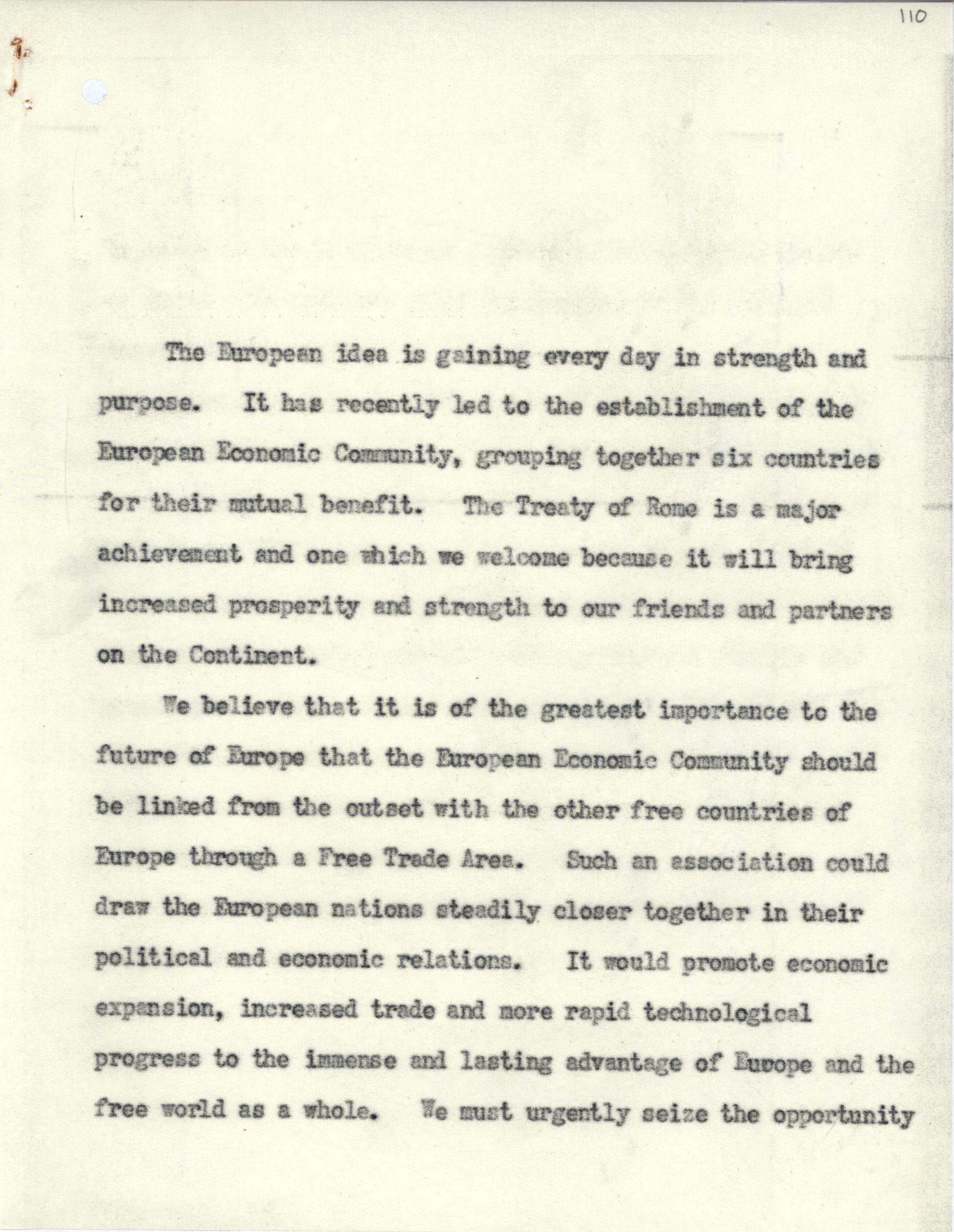

‘The European idea is gaining every day in strength and purpose. […] The Treaty of Rome is a major achievement and one which we welcome because it will bring increased prosperity and strength to our friends and partners on the Continent. We believe that it is of the greatest importance to the future of Europe that the European Economic Community should be linked from the outset with the other free countries of Europe through a Free Trade Area. Such an association could draw the European nations steadily closer together in their political and economic relations…to the immense and lasting advantage of Europe and the free world as a whole.’(Bodleian, MS. Macmillan dep. c.920, fol. 110)

MS. Macmillan dep. c. 920, fol. 110: macmillan to Beddington-Behrens, 17 Feb 1958. Reproduced with kind permission of the Trustees of the Harold Macmillan Book Trust.

In other company, however, it was clear that his approach was much more grounded on the realities of the British position:

‘Of course it might be argued that we could use all our influence to break up the six and to prevent their plan coming into being. I think there would be great dangers in this. First of all, it would be a very wrong thing to do, and secondly, it would probably not succeed.’ (Bodleian, MS. Macmillan dep. c.920, fol. 24)

MS. Macmillan dep. c. 920, fol. 24: Luncheon Speech for European Free Trade Area, 20 Feb 1957. Reproduced with kind permission of the Trustees of the Harold Macmillan Book Trust.

Macmillan realised that Britain could not preserve its economic and political status in Europe from outside a united Europe and, despite his reservations, began to negotiate with European leaders to get Britain in.

Painful process

Informal negotiations with ‘the Six’ began in 1958. Unfortunately for Britain, the same year saw the rise to power of General de Gaulle in France. Although concerned about the escalating war in French Algeria, de Gaulle still saw British membership of the EEC as potentially damaging to France’s international position and especially to its leading role within the EEC.

Britain went to the polls in 1959 and re-elected Macmillan, giving him the mandate to formally apply for Britain to enter the EEC in 1961. Edward Heath, as Foreign Secretary, was sent to Brussels to open formal accession talks.

Politically, British discussion on EEC membership hinged on two issues: the privileged position of the Commonwealth and agricultural subsidies. Both immediately created problems. The British refused to extend Free Trade to food because this would mean removing the existing heavy subsidies given to British farmers and a rise in food prices as a result. The Six, however, also refused to allow the Commonwealth to hold onto its existing trading privileges, despite Macmillan’s attempt to use separate negotiations with the Commonwealth as leverage against the Europeans. For Macmillan, the process was deeply dispiriting. ‘I think sometimes our difficulties with our friends abroad result from our natural good manners and reticence’, he wrote in June 1958.

Gauging the public reaction to the process is difficult. The Labour Party, under Hugh Gaitskell, was certainly hostile. The Conservative Party Archive at the Bodleian does preserve a number of angry letters on the issue; many complain about the perceived ‘betrayal’ of the Commonwealth, others voiced suspicion of European motivations.

Certainly the Conservative Research Department worried that Macmillan’s ‘rational approach based on a simple analysis of our political and economic problems’ might make the attempt to join the EEC sound, publicly, like ‘an act of desperation’. (Bodleian, CRD 2/43/2)

Ultimately, however, public opinion was never put to the test. In January 1963, de Gaulle vetoed British membership of the EEC with his famous comment: ‘non’. Britain would have to wait until 1973 – and endure another humiliating French rejection – before it would finally take a seat in the EEC.

Guy Bud