One of the many exciting things about working on the Summary Catalogue for me has been to dive into our holdings written in foreign languages. Being French, it is always quite thrilling for me to come across a piece of French history in the Catalogue. I have to admit my knowledge of it to be limited to basics, as I chose to study British history at university. Nonetheless, there are dates and names that have stuck with me from my school days, and when I saw the description for the item numbered 47174 in the Summary Catalogue, I knew I had to check out this particular box.

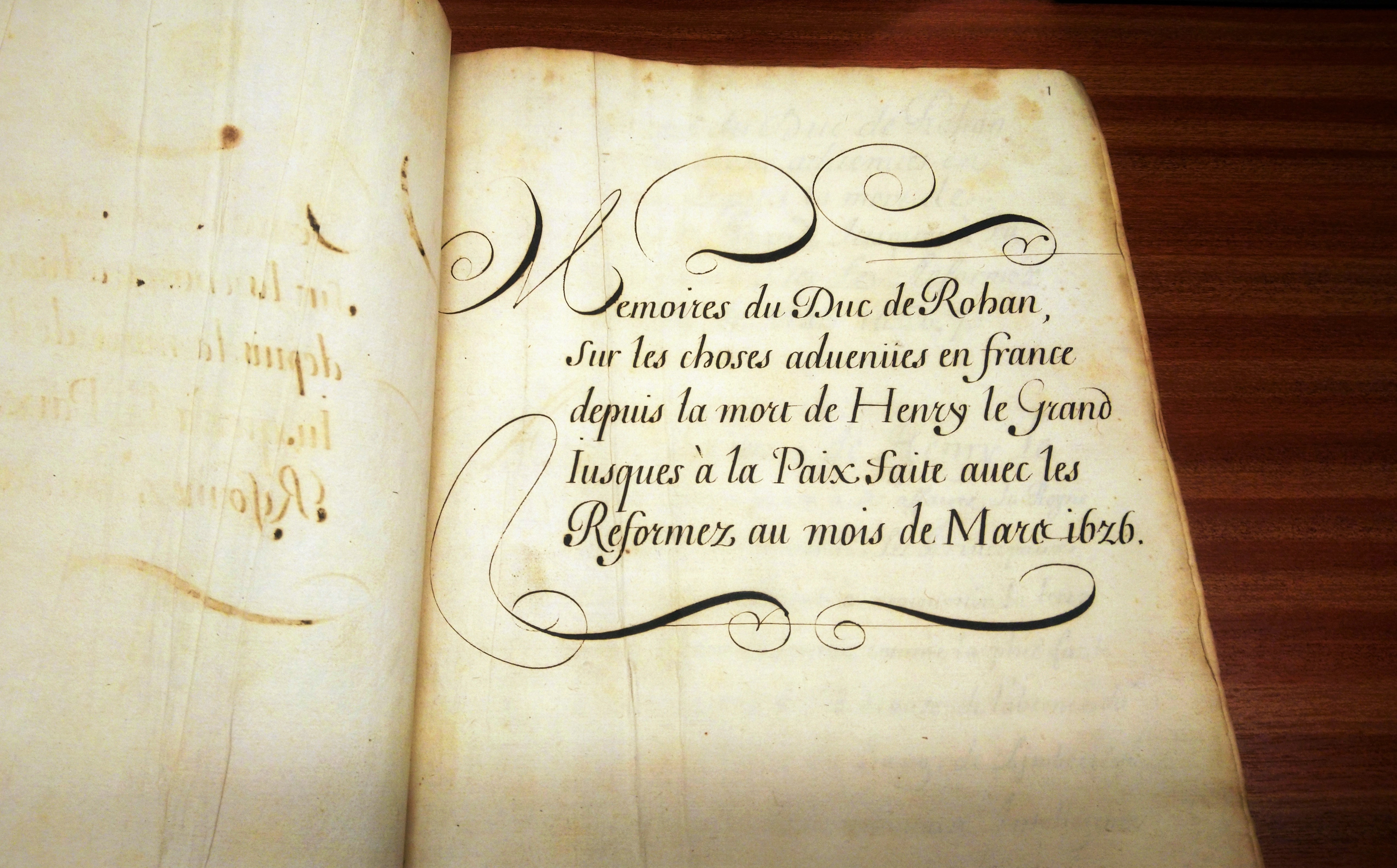

French c. 15 is a copy of Mémoires du Duc de Rohan. The Mémoires were written by Henri II de Rohan, who I think is a fascinating character, and a name you would probably come across while studying 17th century French history.

This is a story that takes us back to early modern France, in the aftermath of King Henri IV’s death, and in the midst of religious unrest. King Henri IV is likely to be one of the most well-known French kings today. His name is tied to the Wars of Religion and to a document called “Edict of Nantes” – let me come back to this later.

What were the Wars of Religion?

Towards the beginning of the 16th century, new religious ideas started to spread across Europe, challenging the dominant Catholic faith. They reached France as well and estimates show that by 1570, around 10% of the French population had converted to Protestantism. Amongst nobles and intellectuals, this proportion was even higher and could have reached as much as 50%.[1] Protestants in France were called the “Huguenots”, but the origins of the name remain unclear. At the time, there was no religious liberty: in the 16th century, Huguenots were heretics and they were persecuted, both by the Crown and by the Church.

In the second half of the century, the tensions between the two religious groups turned into open conflict, culminating in eight different periods of civil war in less than forty years (1562-1598): the Wars of Religion. They include the infamous St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre (23/24 August 1572) in which thousands of Protestants, including many Huguenot leaders, were killed.[2]

The time of the Wars of Religion was a deeply troubled period marked by a lack political stability. While both England and Spain each had two monarchs reigning over those forty years, France was governed by five different kings, some of whom were still children when they accessed the throne. While the four first monarchs were from the Valois family, the last one, Henri IV, was not.

Henri IV and the Edict of Nantes

Henri of Navarre became King of France in 1589 upon the death of Henri III, who did not have any children. However, he was only crowned five years later in 1594 for a good reason: Henri IV was a Huguenot. While he chose to remain a Protestant for the first few years of his reign, his coronation only took place after he converted to Catholicism (1593), pressured by the political tensions. Henri IV nevertheless never had the full trust of either Protestants or Catholics and was murdered in 1610 by François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot.

Henri’s biggest legacy is passing of the Edict of Nantes in 1598. Signed in Nantes, the document was originally known as the “Peace-making Edict.”[3] The Edict was inspired by several preceding edicts that unsuccessfully tried to quell the religious conflicts. It gave Protestants some rights (which came with obligations), and provided them with safe havens and was a sign of religious toleration – still a rare thing across Europe at the time.

The other Henri, Henri II de Rohan

Henri de Rohan was a member of one of the most powerful families of Britany, in Western France. He used to go hunting with King Henri IV, who was his first cousin once removed. Raised as a Protestant, Henri II de Rohan became the Huguenot leader in the Huguenot rebellions that took place after Henri IV’s death, from 1621 to 1629.

Henri de Rohan was a member of one of the most powerful families of Britany, in Western France. He used to go hunting with King Henri IV, who was his first cousin once removed. Raised as a Protestant, Henri II de Rohan became the Huguenot leader in the Huguenot rebellions that took place after Henri IV’s death, from 1621 to 1629.

These rebellions, which are sometimes nicknamed the “Rohan Wars” from the name of the Huguenot leader, arose as the new Catholic King, Louis XIII (Henri IV’s son) decided to re-establish Catholicism in Bearn, a province in the South-West of France (located in Navarre, this was the former homeland of Henri IV). His decision to march on the province was perceived as hostility by the Protestants.

Memoirs of the Duke of Rohan on things that have taken place in France from the death of Henry the Great until the peace made with the Reformists in the month of March 1626

The Mémoires written by the Duc de Rohan are a testimony of the Huguenot rebellions. Written in 17th century French, they give insight on political matters of the time (in this instance, politics and religion are one and the same) and shed light on reasons that drove Protestants to rebel against the Crown. They give details about the relationships that the different protagonists had with each other. While the Bodleian libraries hold a manuscript copy, you can also read Henri de Rohan’s memoirs online here.

After the Mémoires

The aftermath of the Huguenot rebellions was not favourable to Protestants: in 1629, as the Huguenots lost the last conflict of the rebellions, a peace treaty was signed in Alès. The treaty banned Protestants from taking part in political assemblies and abolished safe havens. Henri de Rohan, who was the leader of the Huguenots, had to go into exile: Venice, Padua, and Switzerland. By 1634, Louis XIII had pardoned him, and Rohan was tasked with leading French troops first against Spain, and then against Germany in 1638. Henri de Rohan died from a battle wound in April 1638.

The Edict of Nantes of Nantes was completely revoked in 1685 by King Louis XIV. Freedom to worship was introduced again in France in 1789 in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,[4] a consequence of the French Revolution.

You can view the catalogue of this manuscript in the Bodleian Archives and Modern Manuscripts interface. Once the library reopens, it will be available to request and view in the Weston Library Reading Rooms.

References:

[1] Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. Encyclopedia of Protestantism, New York: Routledge, 2004, vol. 2, p. 736

[2] The exact number of casualties is unknown. Estimates range between 10,000 and 30,000.

[3] The original French term is “Édit de pacification.”

[4] The original French name is “Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen.”

Read more:

Clarke, Jack A. Huguenot Warrior : the Life and Times of Henri De Rohan, 1579-1638, 1966

Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. Encyclopedia of Protestantism, New York: Routledge, 2004

Holt, Mack P. The French Wars of Religion, 1562-1629, 2005.