As mentioned in our August blog and the recent blog post about the physician Henry Holland, the Bodleian Libraries acquired a collection of letters last year which included letters between Maria Edgeworth and Henry Holland and which has now been fully catalogued. In his memoirs, Recollections of Past Life (1868), Henry Holland recalls how he became acquainted with Maria on a visit to Ireland in 1809, after which they maintained an ‘unbroken and affectionate correspondence for more than forty years’ that would have ‘formed a volume’ in itself.

Sir Henry Holland, Bart., M.D., F.R.S., D.C.L., Oxon, &c., &c from Barraud & Jerrard, ‘The medical profession in all countries, containing photographic portraits from life’, 1873-74 (London) (image from U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections)

Sir Henry Holland, Bart., M.D., F.R.S., D.C.L., Oxon, &c., &c from Barraud & Jerrard, ‘The medical profession in all countries, containing photographic portraits from life’, 1873-74 (London) (image from U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections)

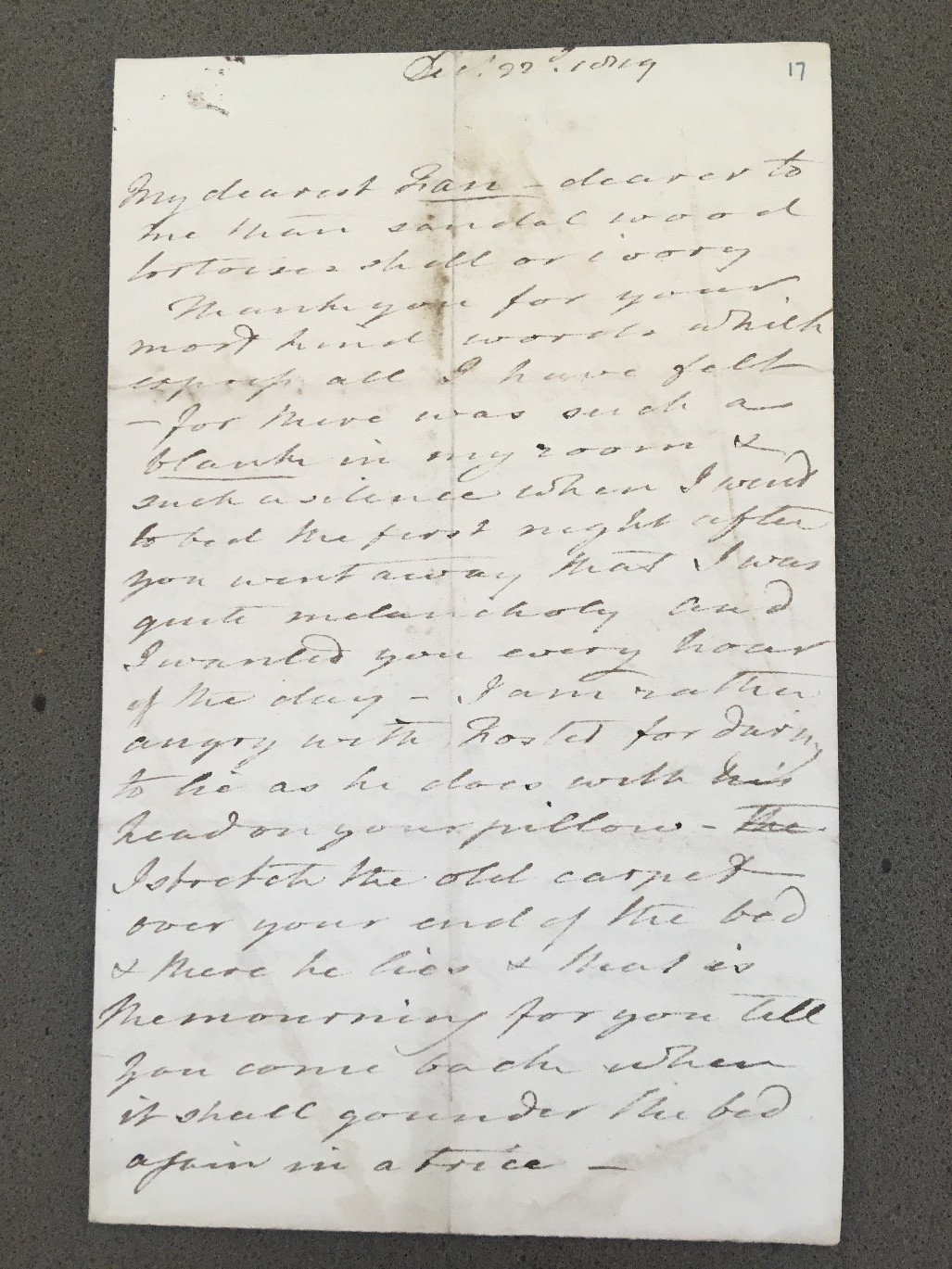

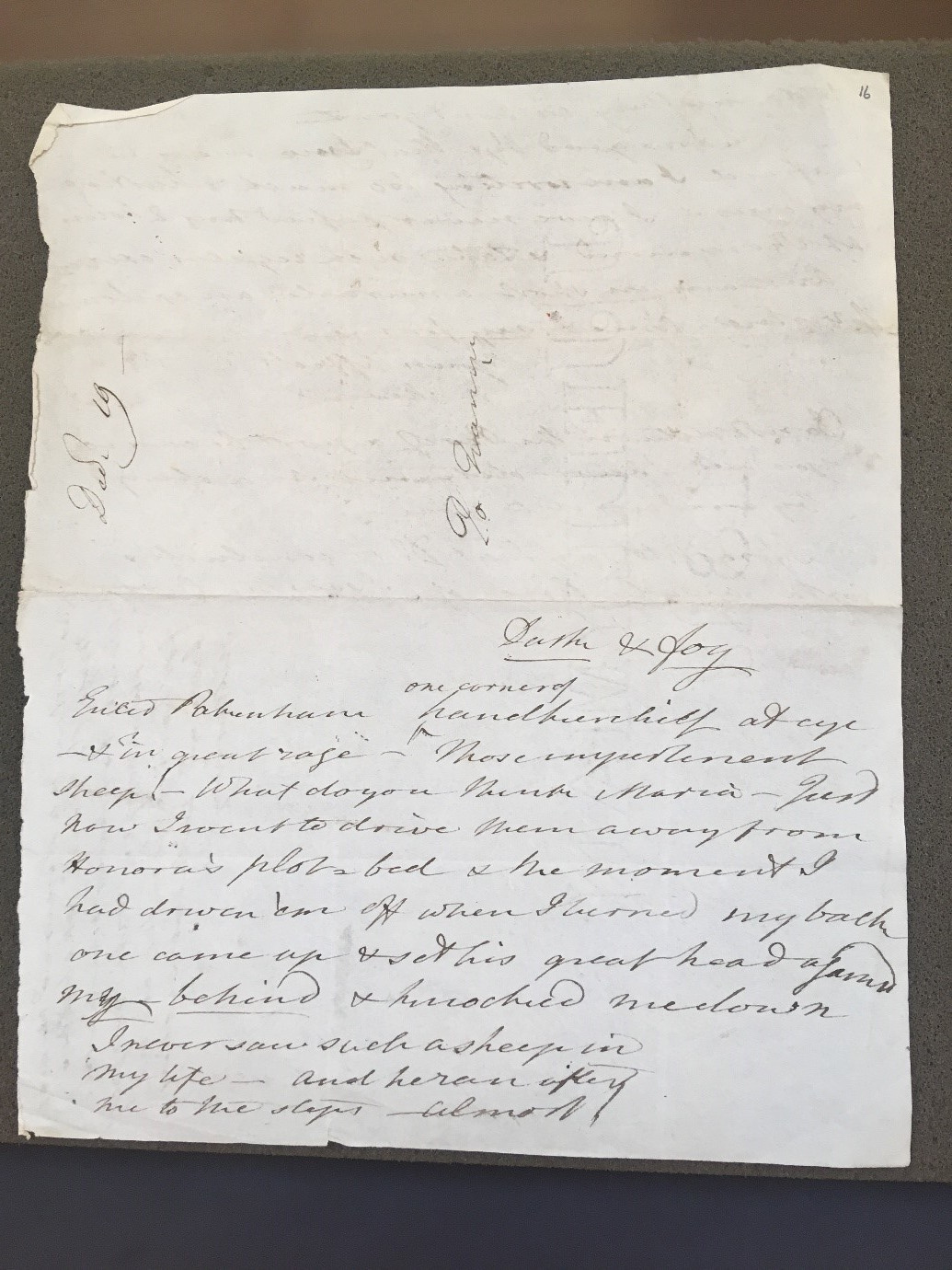

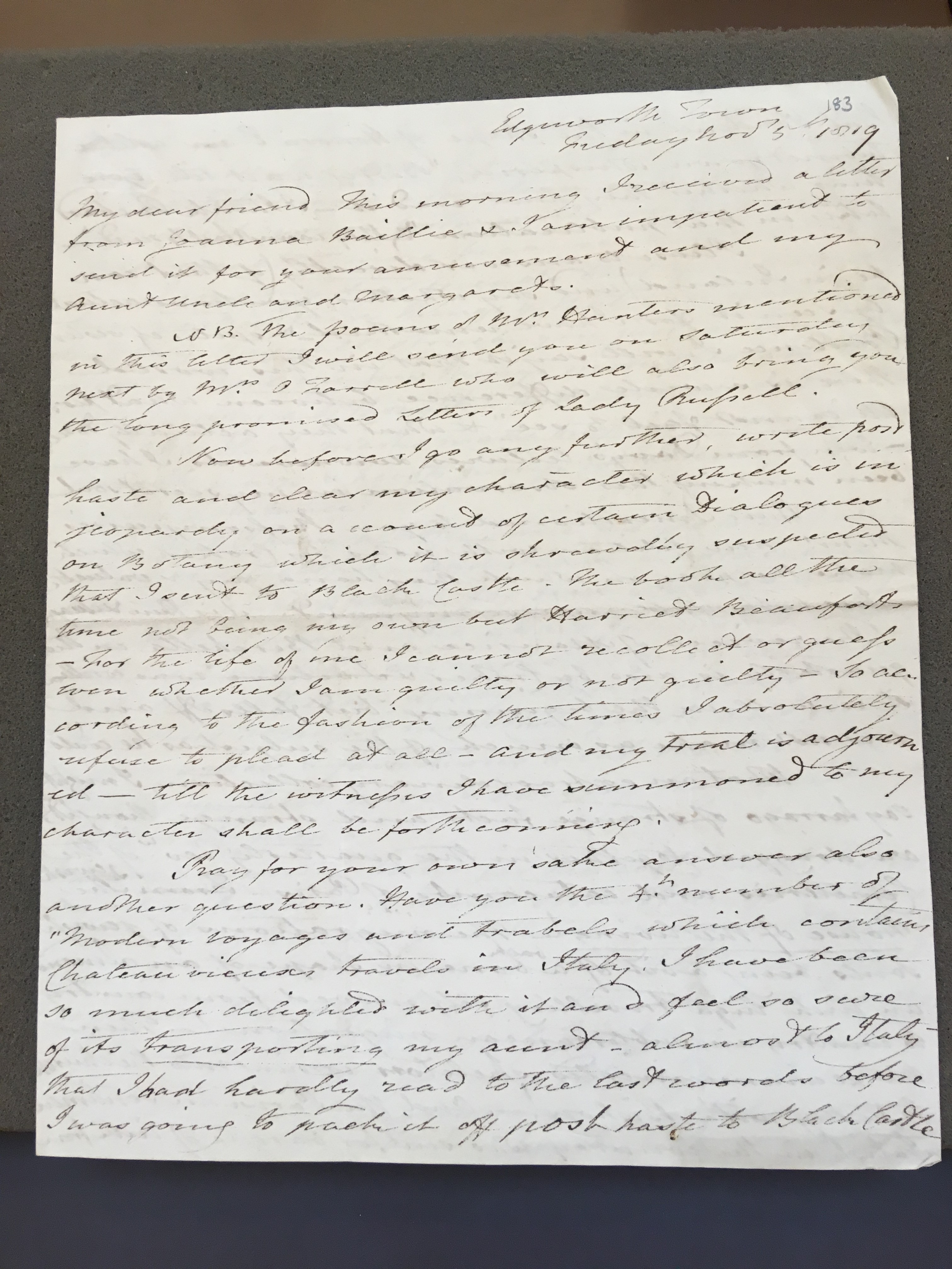

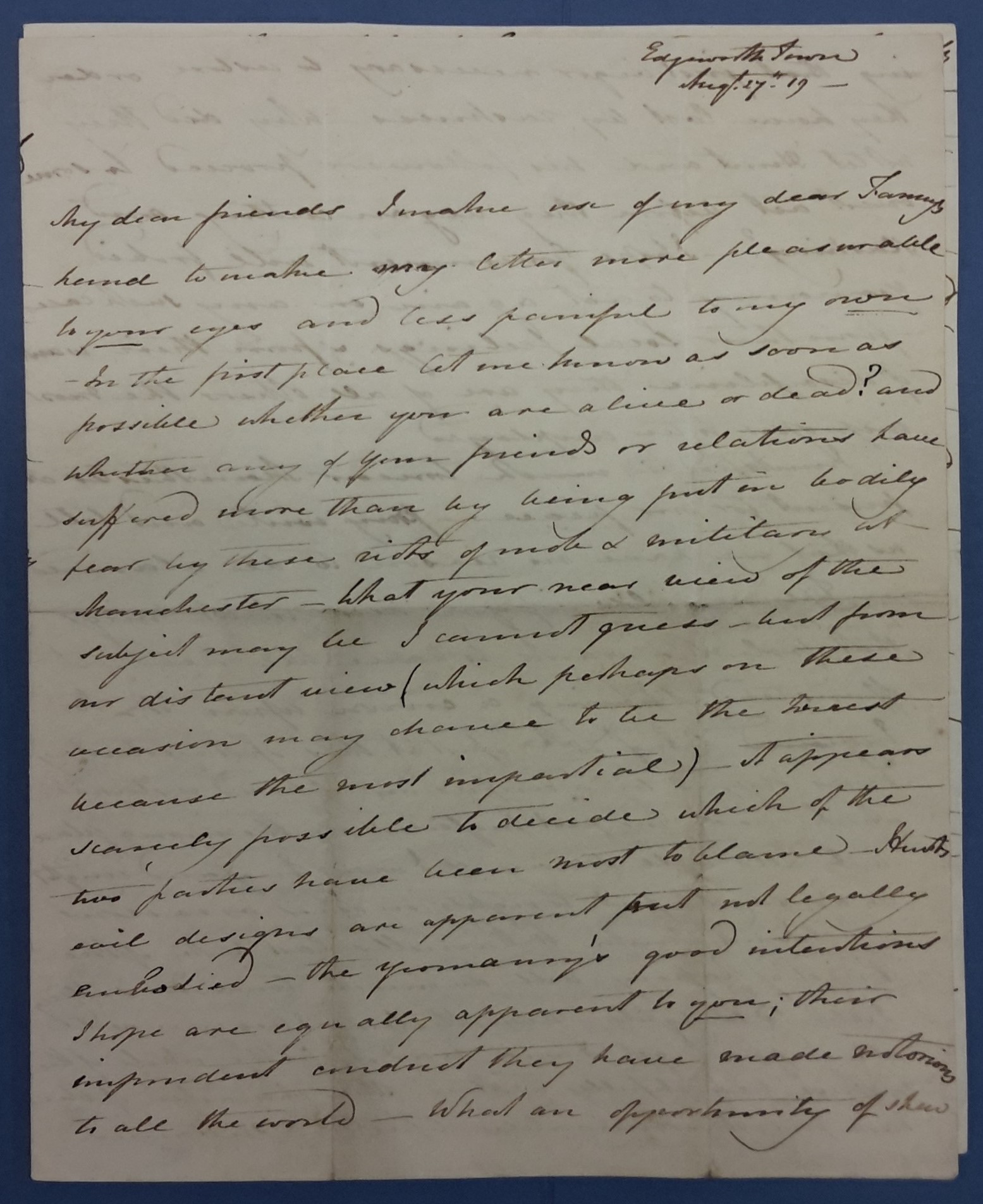

Holland noted in that same memoir that he admired Maria’s letters for their intellectual ‘discrimination and ability’. These characteristics are evident in her letter to Henry Holland dated 25th February 1820 (MS. 16087/1). Here too we see a lively variety of everyday domestic details and ambitious intellectual forays into discussion of contemporary literature and politics on an international scale. Writing from the home of her beloved Aunt Margaret Ruxton at Blackcastle near Dublin, Maria begins with updates on the ailments of her step-aunt Charlotte Sneyd and half-sister Fanny, and goes on to describe the visit of her step mother Frances Beaufort to the latter’s parental home in Cork. Just as we have sought to identify interesting material for the readers of our online blog, Maria is anxious not to bore her high-society friend with the humdrum happenings of her daily life in rural Ireland:

And are these dull domestic details all I can tell Dr. Holland who is living in the middle of all that is gay & fashionable and learned and wise, in the scientific, literary, political, and great world in London?

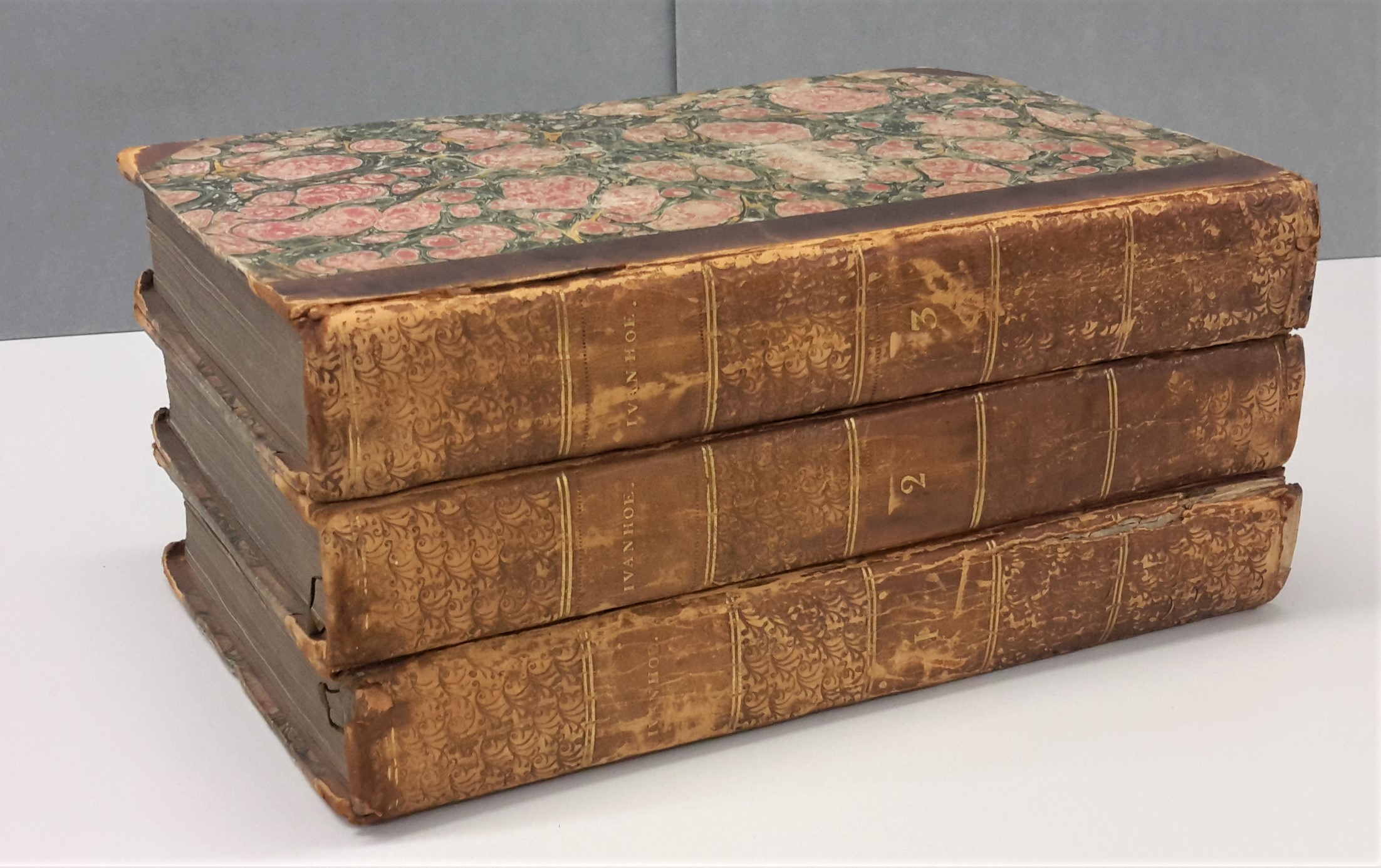

In fact the letter is far from dull. Edgeworth claimed not to have Holland’s ‘intrepid industry nor your art of making eight & forty hours out of the day’. Yet over six pages she certainly makes a good go of it. She crams in her comments on the recently published Ivanhoe (‘a great proof of Walter Scott’s talents’, discussed in last month’s blog), describes her continued labour of correcting the proof sheets of her father’s ill-fated memoirs (‘Till I have corrected the last proof sheet I shall never stir’), and she offers Holland a ‘sunbaked urn’ recently found in an Irish tunnel ‘bones and all’ to satiate his antiquarian interests. Then, Maria turns to current affairs and future continental travel plans:

By a letter from my brother Sneyd [Edgeworth] who

is at Paris we hear that the Duc de

Berri’s assassination [on the 14th Feb] has created much

less sensation there than we could imagine

– If they restrict the press I think it

will fly and in its explosion overturn

the throne – In these days the press /is\ in

an over match for cannon – and It is

an engine far more dangerous to

meddle with than any of the cannon

that are “laying about”

If there be not an explosion or a

revolution in Paris before the end of

next month I shall be there with two

of my sisters Fanny & Harriet

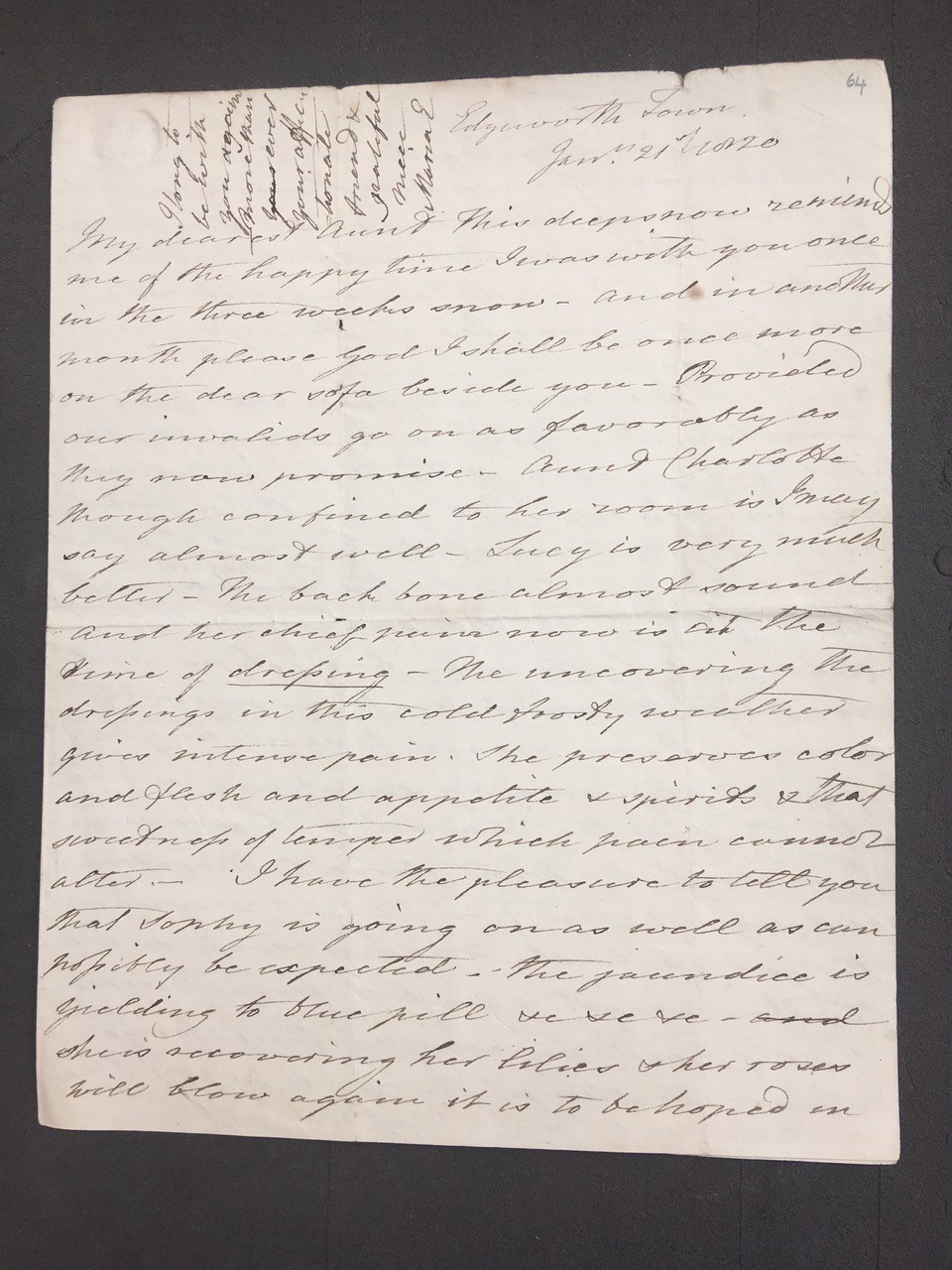

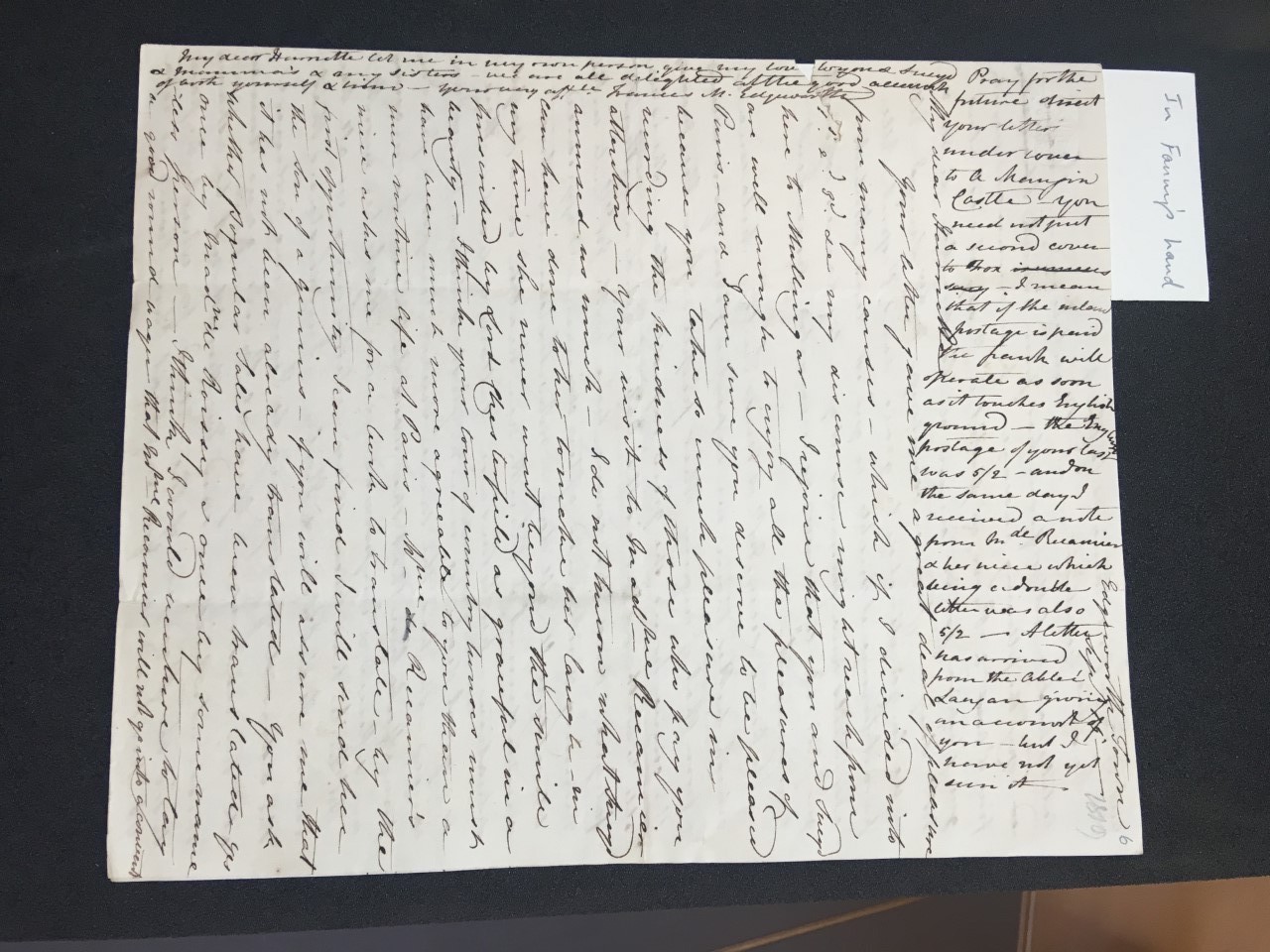

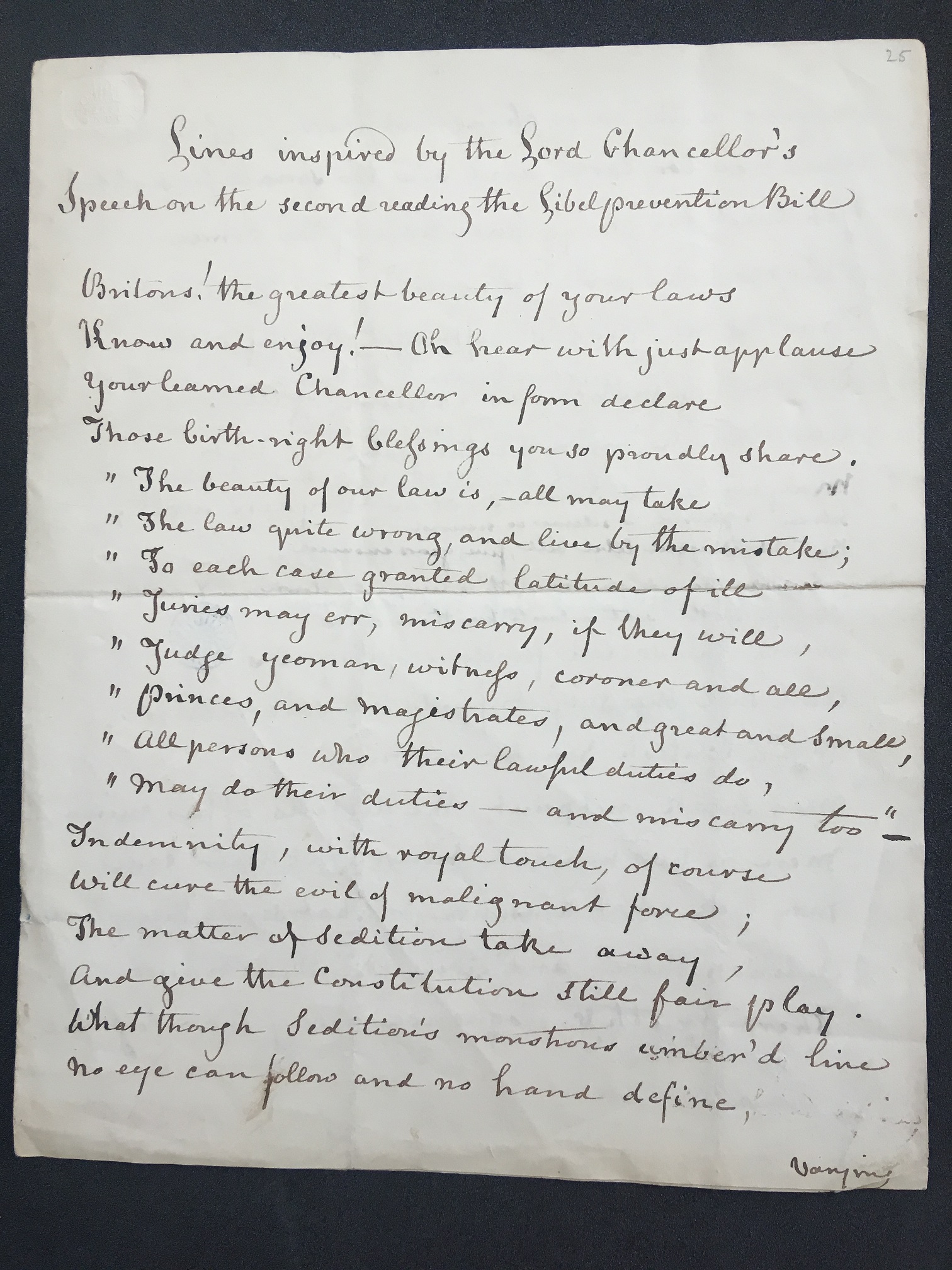

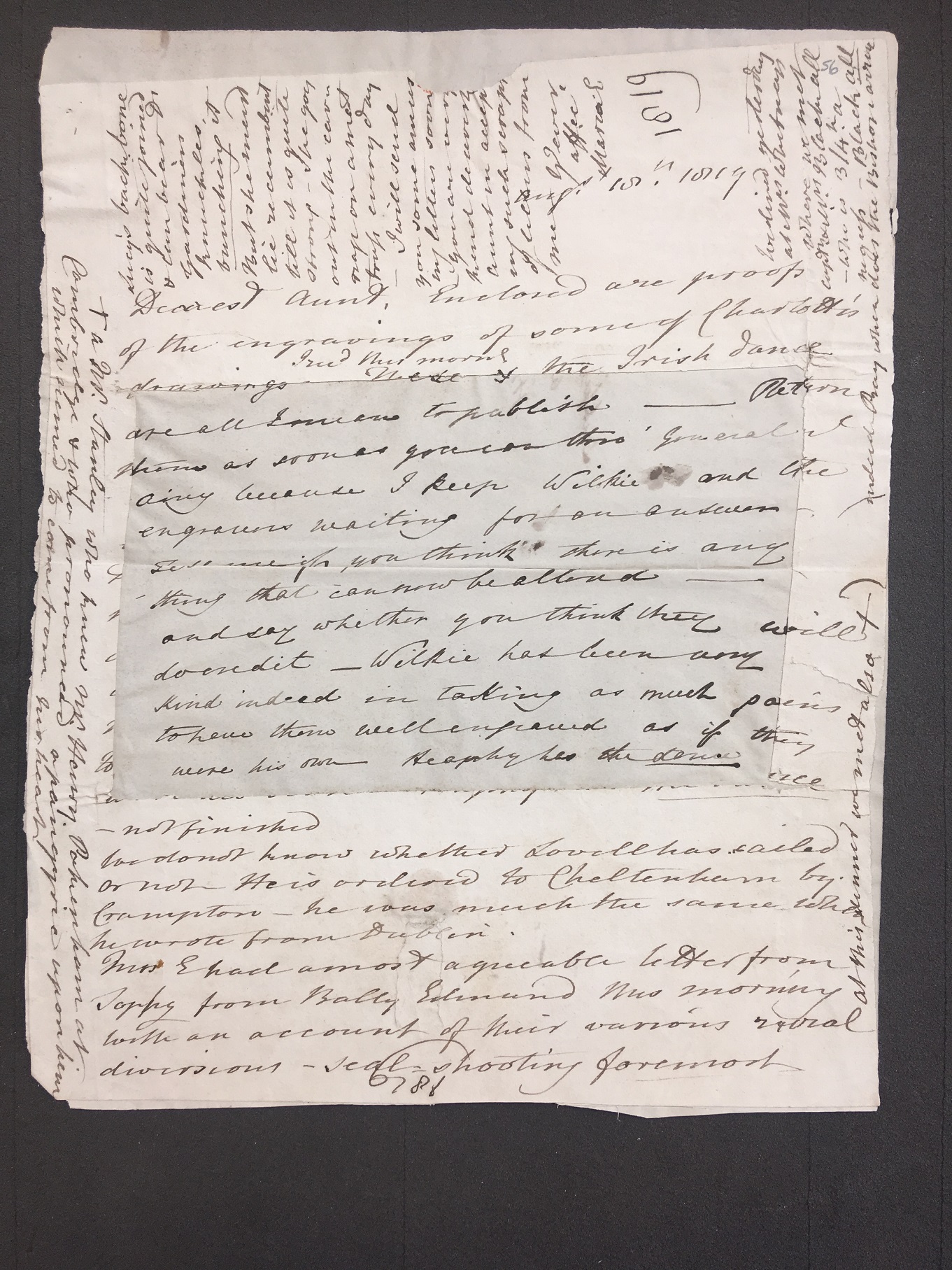

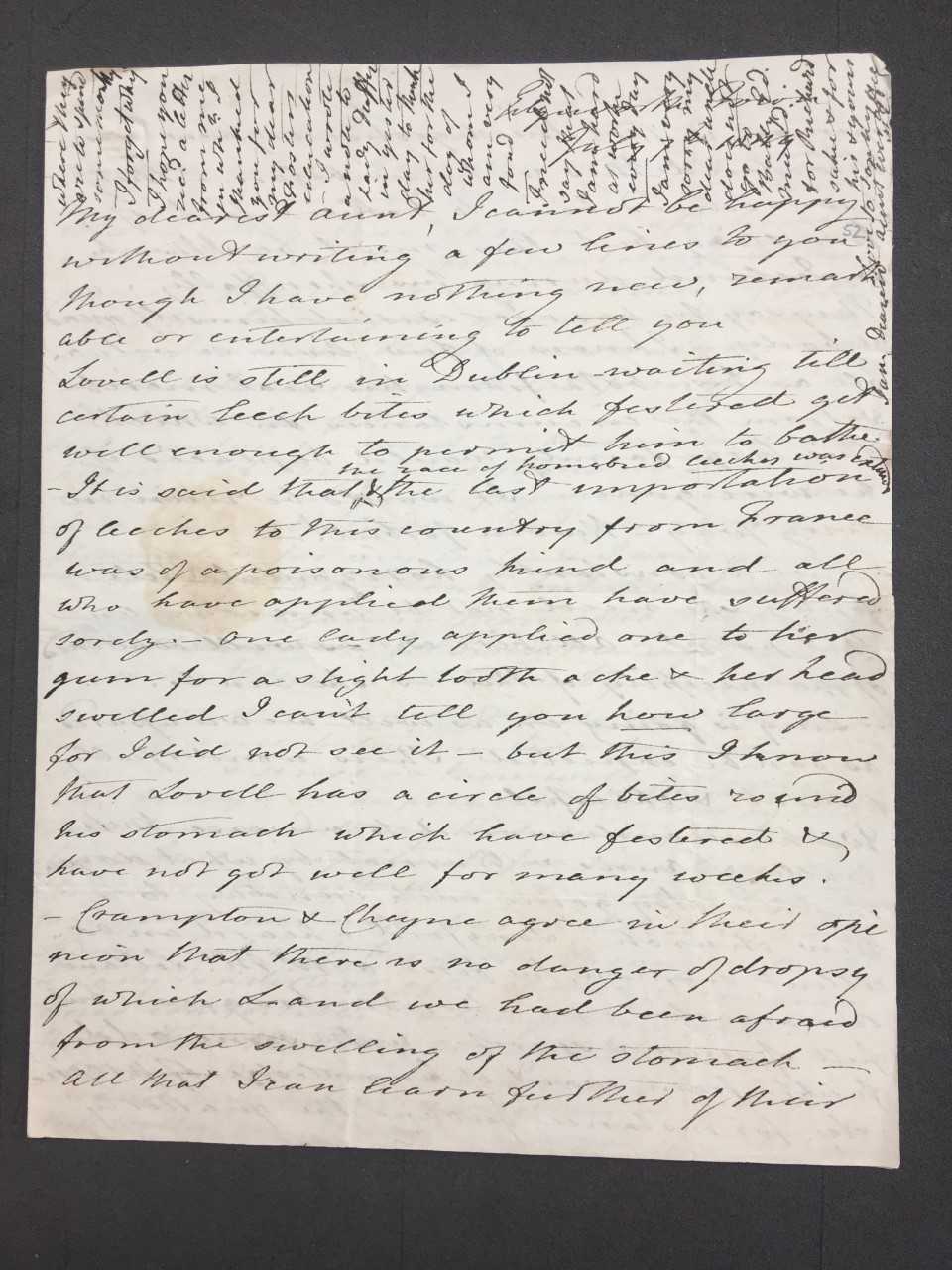

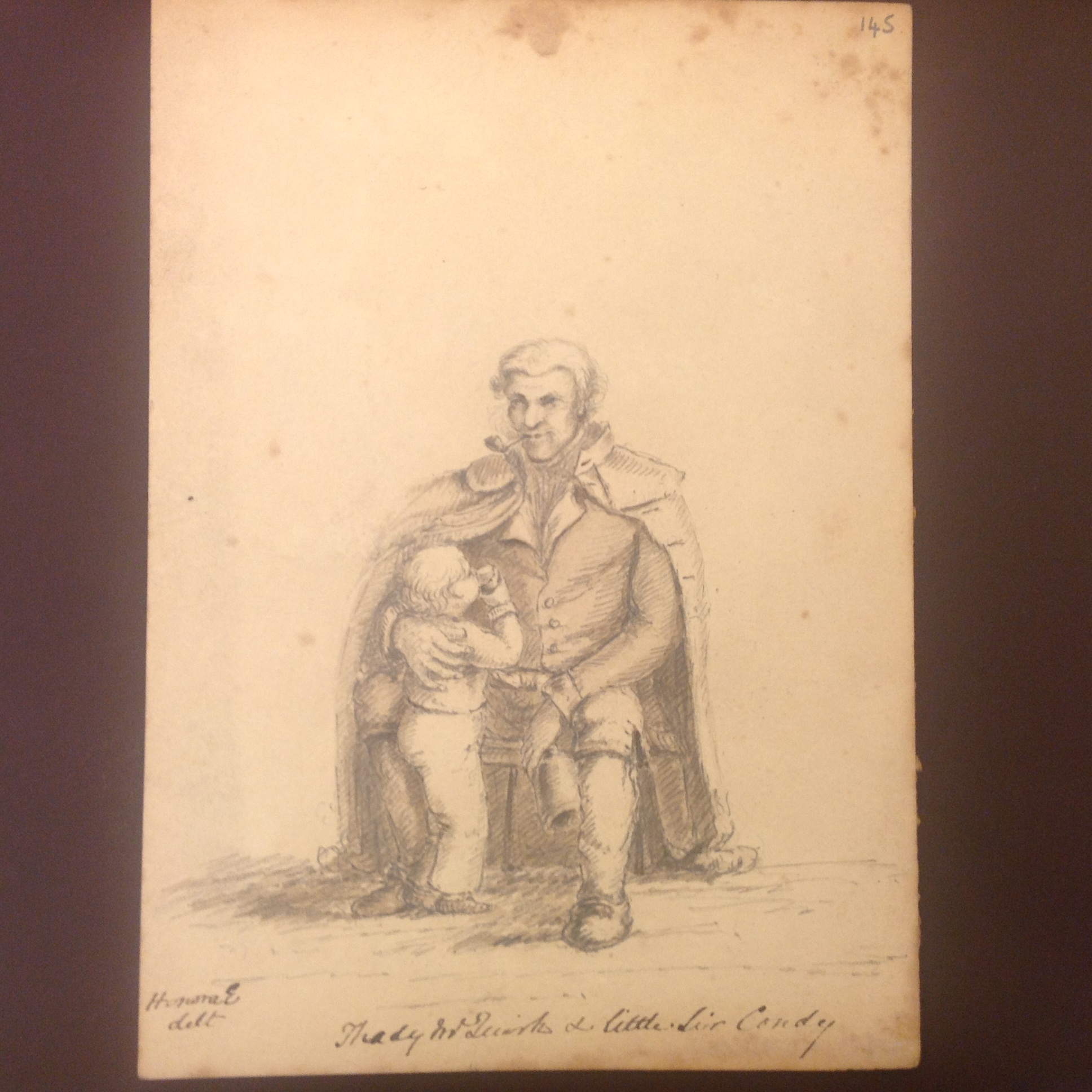

Page of letter from Maria Edgeworth to Henry Holland, 25 Feb 1820, MS. 16087/1

Page of letter from Maria Edgeworth to Henry Holland, 25 Feb 1820, MS. 16087/1

Full transcription of letter from Maria Edgeworth to Henry Holland, 25 Feb 1820, MS 16087/1

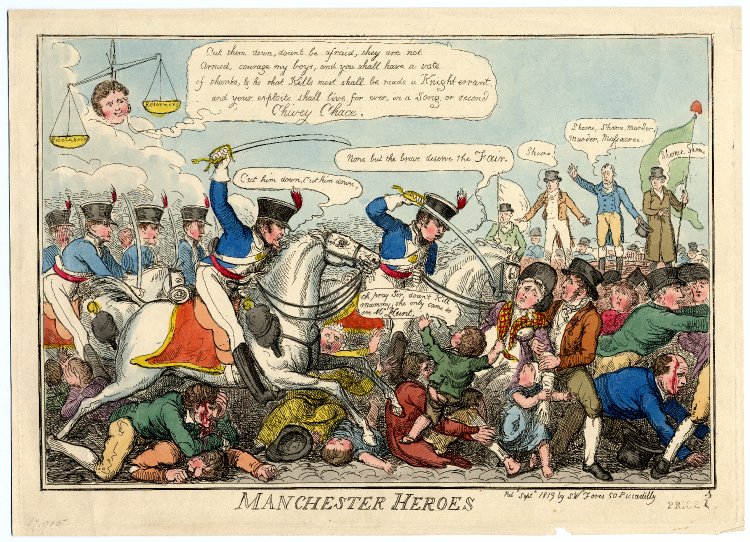

Recent events had proven that stifling the freedom of press was dangerous to national order. When Britain had reinstated press censorship as part of the Six Acts following the Peterloo Massacre in the previous year (an event discussed by Maria in another letter), protests erupted across the country. Maria’s shrewd predictions in this letter proved largely correct. The assassination of Charles Ferdinand Duc de Berry (the heir to the French Bourbon throne stabbed by the anti-monarchist Louis Lavel as he left the opera) was indeed used by the French government to validate the reinstatement of press censorship in March 1820. Riots broke out in retaliation against the bill, but were soon quelled by the Royal Guard. This imposition of peace allowed the Edgeworths to proceed with their planned trip to Paris at the end of March 1820 and the Bourbons to cling onto their throne for another decade.

Engraving of The Assassination of the Duke of Berry by Charon, Louis-François (1783-1831?), source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Engraving of The Assassination of the Duke of Berry by Charon, Louis-François (1783-1831?), source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

In the context of the UK’s recent departure from the European Union, Maria’s letter to Henry Holland reminds us of the effects that political events can have at the micro and macrocosmic level: it can mean inconvenient disruptions to carefully planned family holidays, or shake the foundations of an entire nation. Maria’s comments also help to demonstrate that Irish-continental connections were often as strong as, or could serve as a means to strengthen critique of, Anglo-Irish ones.

Much has changed since we started Opening the Edgeworth Papers a year ago and this is our final blog post. Our twitter account and blog posts have allowed us to disseminate our work around the world. Our monthly transcriptions have even appeared on Edgeworthtown’s new town centre mural. We’ve curated a successful exhibition ‘Meet the Edgeworths’ at the Bodleian Library. This month, we had the honour of hosting the second Marilyn Butler Memorial Lecture, at which Professor Clíona Ó Gallchoir (University College Cork) delivered a fascinating paper about theatricality in Maria’s works. A recording of the lecture is available online.

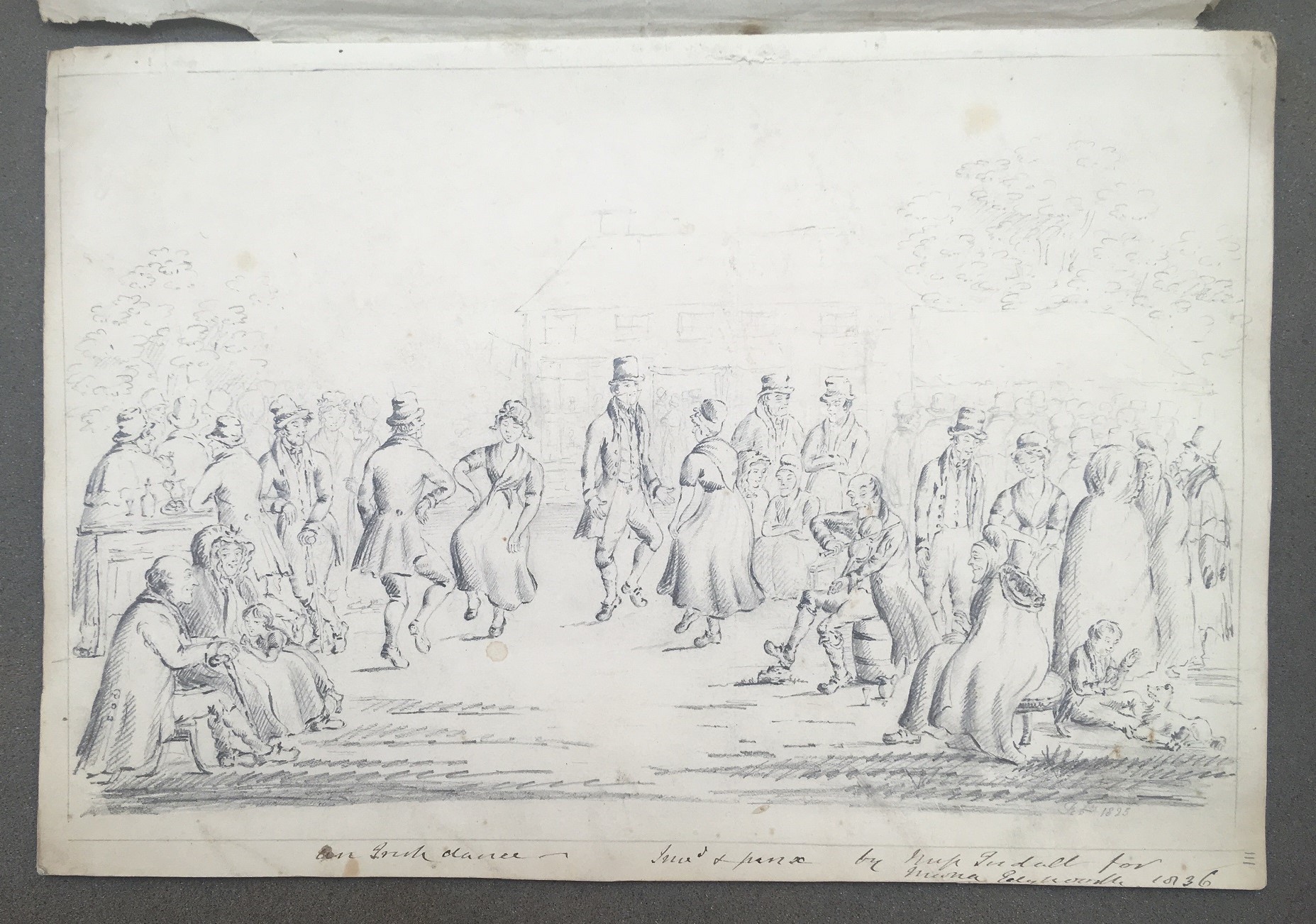

Edgeworthtown’s town centre mural. Images courtesy of Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull.

Edgeworthtown’s town centre mural. Images courtesy of Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull.

One of the joys, and occasionally challenges, of working on the Edgeworth family is discovering new material that has come to light. Since starting the project a year ago, we’ve had twitter followers send us information and images of previously unknown letters in private collections. Other items have appeared at auction, most notably at the Cotswold Auction Company’s sale this month. This major collection of over thirty of Maria’s previously unknown manuscript notebooks containing drafts of her novels, caches of letters to publishers, and printed books from the Edgeworth library took the field by storm when it dramatically exceeded auctioneers’ modest expectations and reached £147,000: evidence, perhaps, of the revived commercial attraction of one of the nineteenth century’s most successful authors. Thankfully, important lots were purchased by academic institutions, namely Princeton University Library and the National Library of Ireland, which will remain accessible to future generations of scholars.

Although this is our last blog post, this isn’t the last you will hear from the Edgeworth Papers Project team! On Sunday 29th March, we will be holding a masterclass on the Edgeworth Collection as part of the Oxford Literary Festival. The event is being held at the Weston Library Lecture Theatre in Oxford at 12 noon, where we will be talking about a selection of items from the archive. All are welcome, and tickets can be purchased online. You can also continue to follow updates on the project on Twitter @EdgeworthPapers. You can also access further content, including a recorded performance of a manuscript dramatic fragment by Maria, at our Great Writers Inspire Page. We hope that you will continue with us on this journey working on a fascinating collection that is only just beginning to reveal its secrets.

– Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull