As we struggle through yet another rainy June in Oxford, we cast our gaze back to the more sunny events in Ireland described by Maria Edgeworth in a letter from 17th June 1819 to her paternal Aunt Margaret Ruxton (1746-1830) (MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.50-51)—written in cross style on the last page and writing around the sides to save paper. In past posts, we’ve considered some of the smaller objects that make up the Edgeworth papers—scraps and fragments that were treasured not for their intrinsic worth, but for their sentimental value. The focus of this post, Maria’s beloved dog Foster, is thankfully not housed in the Bodleian. But as Maria’s letter demonstrates, despite his diminutive size, Foster was a highly-valued member of the extended Edgeworth family.

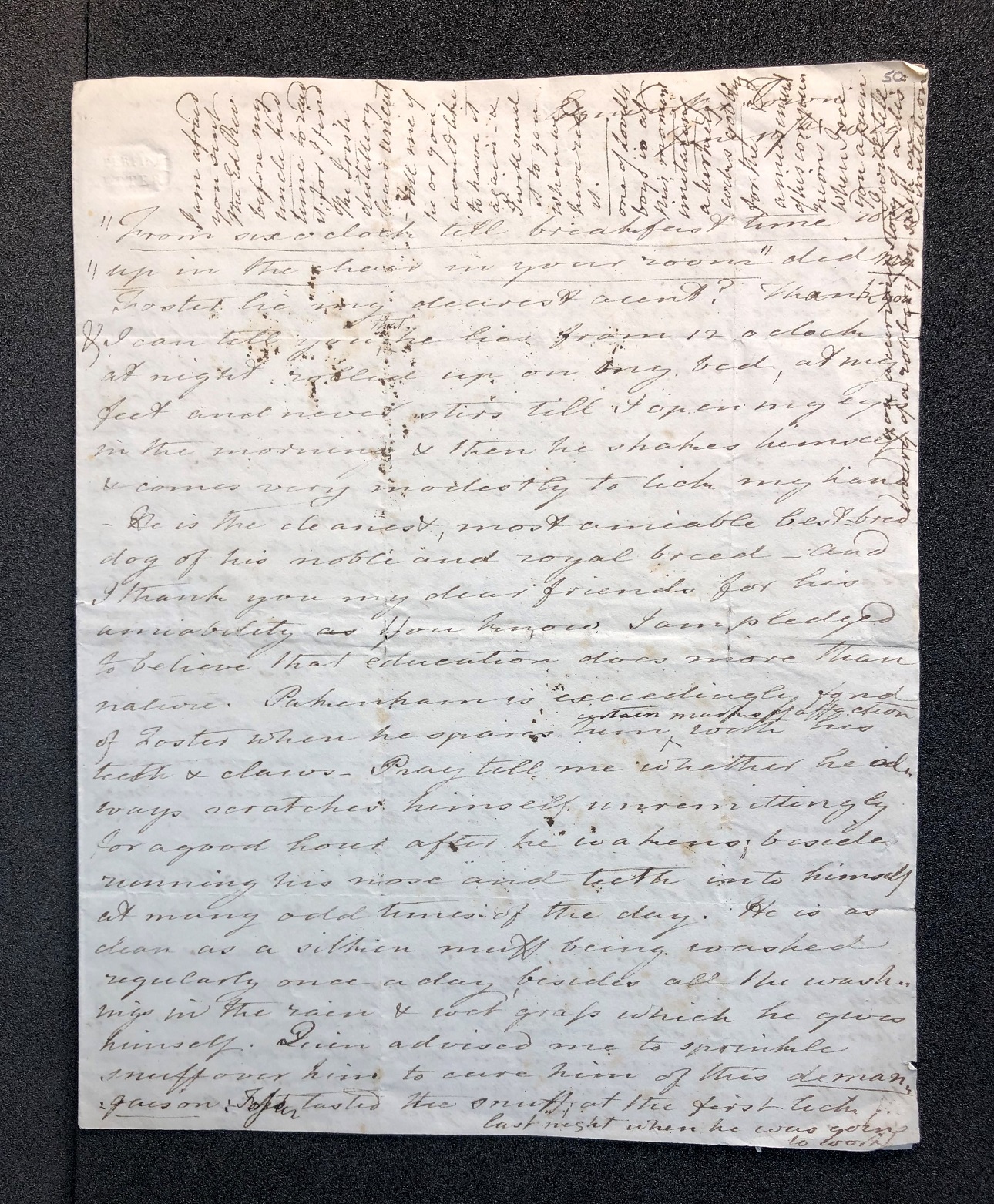

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to her paternal Aunt Margaret Ruxton, 17th June 1819 (MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.50r)

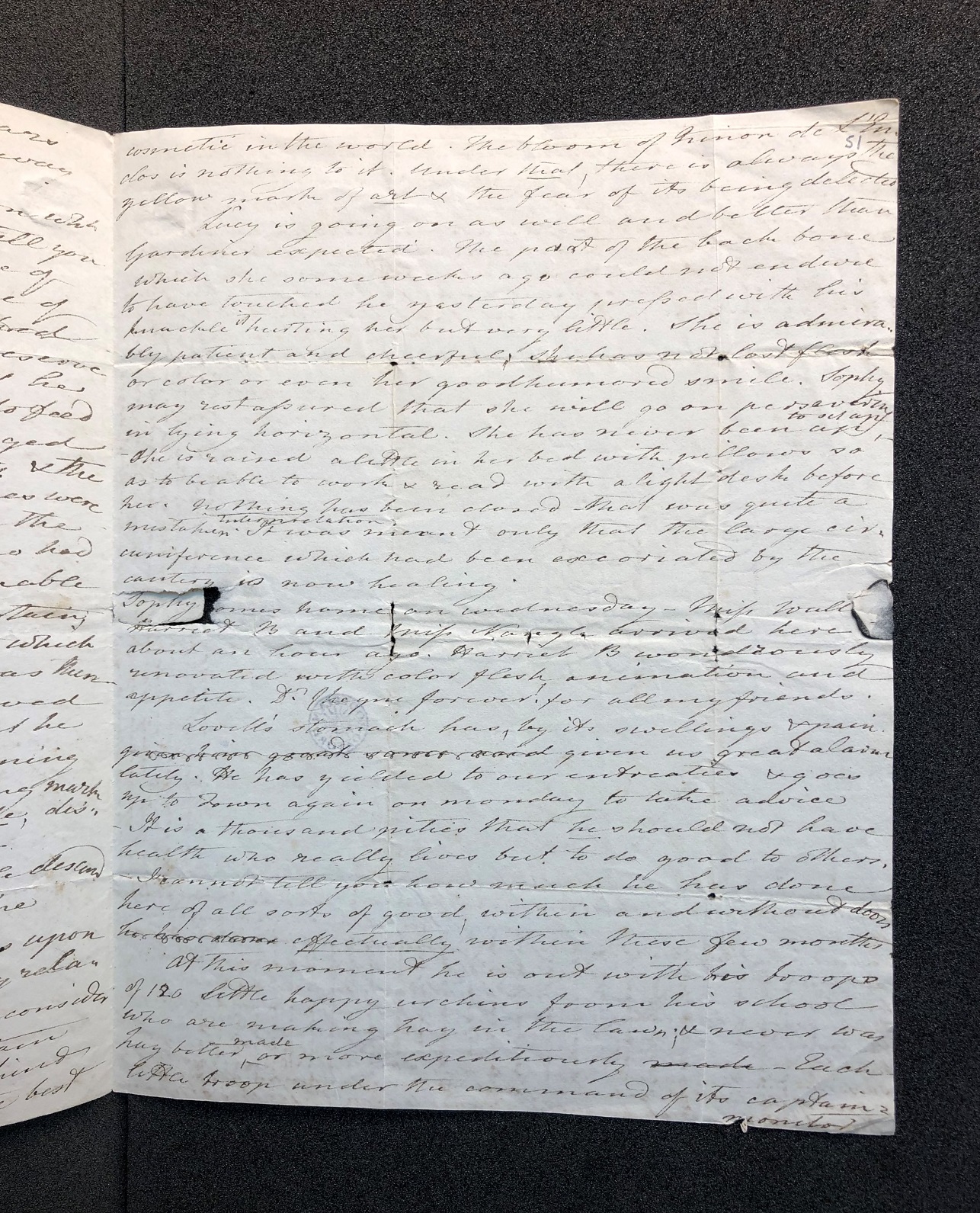

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to her paternal Aunt Margaret Ruxton, 17th June 1819 (MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.50v)

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to her paternal Aunt Margaret Ruxton, 17th June 1819 (MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.51r)

Letter from Maria Edgeworth to her paternal Aunt Margaret Ruxton, 17th June 1819 (MS. Eng. lett. c. 717, fol.51v)

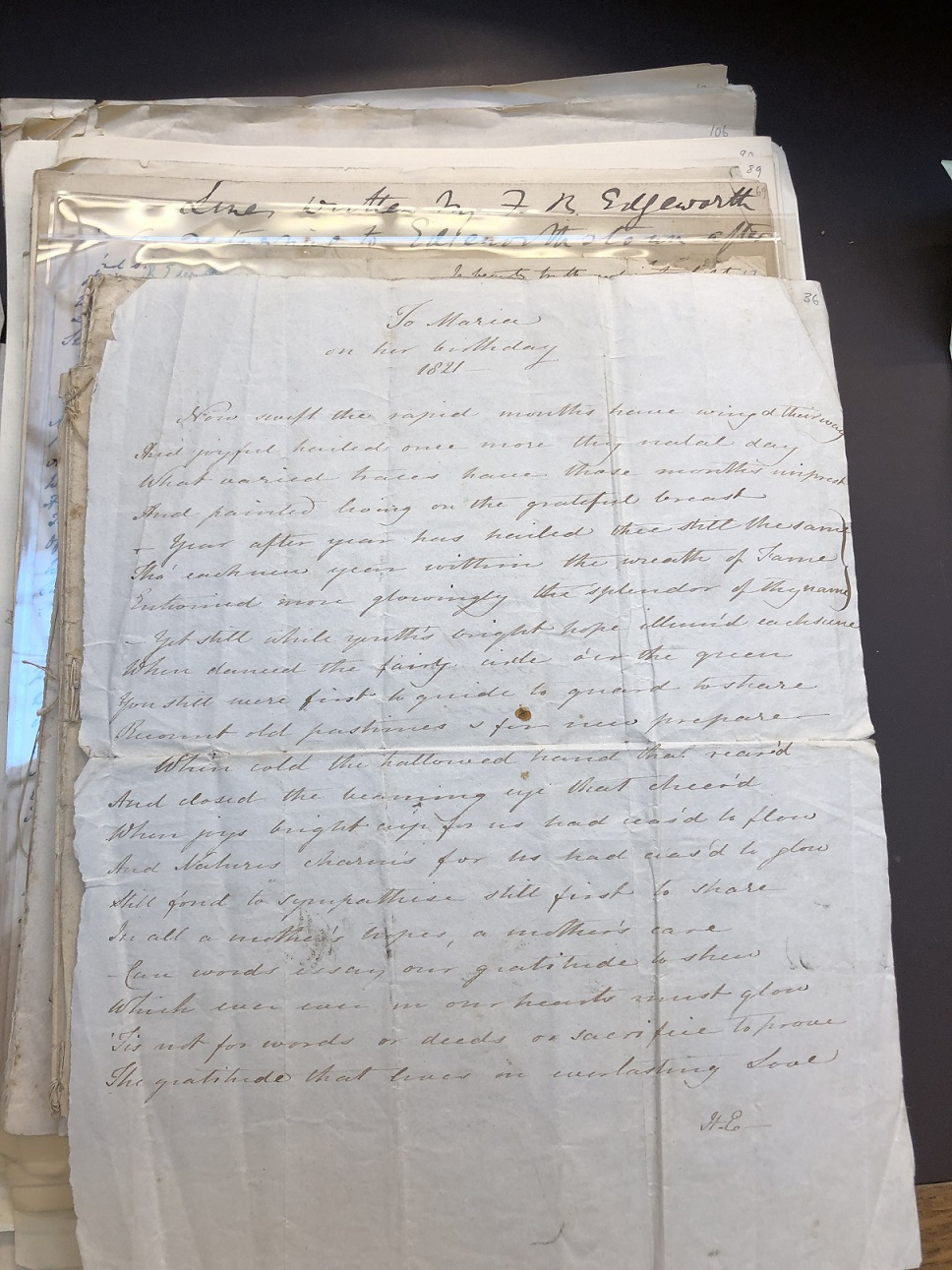

Transcription of MS. Eng. Lett. 717, fols.50-1

Like any good boy, Foster comes with his own backstory. Prior to leaving Ireland for England with her sisters late in 1818, Maria visited the family home of John Foster, latterly Baron Oriel (1740-1828)— a good friend of her recently deceased father Richard Lovell Edgeworth, and the last speaker of the Irish House of Commons prior to its dissolution by the Act of Union in 1800. On this particular visit, Maria was so taken by Foster’s King Charles spaniel that he promised her one of its puppies. When Maria returned to Ireland in June 1819, her Aunt Ruxton presented her with a new addition to the family that fulfilled Foster’s promise—a beautiful spaniel puppy, whom she named after her father’s friend.

Writing excitedly to her Aunt shortly after Foster’s arrival at Edgeworthstown, Maria recalls in her letter the superlative devotion of her ‘dearest, most amiable bestbred’ dog to his mistress. Among the Edgeworth papers, there is a pencil portrait by Colonel Stevens of a regally-posed Foster reclining in front of Edgeworthstown House (MS Eng Misc c.901, fol.90) , Maria’s description of her new puppy evidences his valued position as the family’s model pet— one who never ‘stirs til I open my eyes’, is as ‘clean as a silken muff’, is friendly enough to withstand the playful grasp of Maria’s seven-year old half-brother Michael Packenham, and entertains the whole family through his comedic reaction to tasting the snuff intended to relieve his ‘Démangeaison’ (itching). Much like Lady Frances Arlington’s dog in Maria’s novel Patronage (1814), who distracts the audience when he performs tricks during a private theatrical performance, Foster clearly succeeded in stealing the hearts of the entire extended Edgeworth family.

Pencil portrait by Colonel Stevens of Foster in front of Edgeworthstown House (MS Eng Misc c.901, fol.90)

Maria clearly valued Foster for his companionship. She could, after all, ‘speak forever’ on ‘the subject’ of her puppy. Yet there is some comedic value in the fact that Foster was a King Charles spaniel. This ‘royal breed’, as Maria refers to it, of toy spaniel has been associated with the English Monarch since Lucas de Heere painted a pair curled at the feet of Queen Mary I in 1558. In her letter, Maria takes great pride in telling her aunt how ‘My Fosters [black] mouth proved his noble descent’ from the rare, prized breed owned by English aristocrats. Indeed, Maria shockingly recalls how King Charles Spaniels were valued so much by ‘Late the Duke of Norfolk’ that he reportedly fed their puppies to his ‘German owl’, and deceived Queen Charlotte with a worthless ‘cur’, mongrel, to ‘to preserve [his] […] exclusive possession’ of the breed. Yet Foster was the gift of, and named after, an Irish politician who had stalwartly fought – from within William Pitt’s government— for Irish economic prosperity and peace during the long years of struggle over the Union of Great Britain and Ireland.

Whilst Maria’s references to Foster’s aristocratic breed may be ironic, his name choice demonstrates the value Maria placed in his namesake as an individual. In Maria’s fictional works, dogs are often named after the characters with whom they share personality traits. In Maria’s earlier novel, Belinda (1801), for example, West Indian white creole Mr Vincent names his dog after his black servant Juba in recognition of their shared loyalty to their master (‘Well, Juba, the man, is the best man – and Juba, the dog, is the best dog, in the universe’). Similarly, in her moral tale for children, The Little Dog Trusty (1801), the story’s blameless titular canine is renamed Frank after the narrative’s equally well-behaved child (‘Trusty is to be called Frank [to] […] let them know the difference between a liar and a boy of truth’) (MS Eng Misc c.901, fol.140). By naming her dog after John Foster, Maria can be seen as complimenting the former speaker for his amiable qualities and loyal character. Indeed, Maria was writing her Father’s memoir with her new dog Foster by her side, and she may well have been thinking of two independent-minded landowning men important in her life—men who had sought to provide the kind of guidance and care to the poor and neglected local Irish tenants described in the second part of this letter, and painted by her half-sister Charlotte (MS Eng Misc c.901, fols.58-60).

‘Vignette for Dog Trusty’ by F.M.W., 1842 (MS Eng Misc c.901, fol.140)

Sketch by Maria’s half-sister Charlotte, ‘After dinner at a Bog’ (MS Eng Misc c.901, fol.58)

Sketch by Maria’s half-sister Charlotte, ‘Irish laborers from the life’ (MS Eng Misc c.901, fol.60)

Early in her letter, in a compliment to her aunt who had raised Foster from a puppy, Maria remarks on his amiability, observing that she is ‘pledged to believe that education does more than nature’. Her belief in the benefits of a good education is evidenced in the scenes of rural labour and education among ‘troops’ of young children with which she furnishes her aunt at the end of the letter and which are also found frequently in her fiction. Virtue is something that must be ‘fostered’ in the young. And we see that in the story of Lovell’s (foster) care for a fatherless Irish boy in his school at Edgworthstown who is described working happily alongside his fellows haymaking in the closing (densely crossed) paragraphs at the end of Maria’s letter.1 The boy’s father has been executed having gone to the bad and fallen among thieves. Maria reports the neighbourhood view that his son, brought up to virtue in his mother’s family, might have influenced him against such criminality. Lovell prompts the boy’s schoolfellows to undertake small amounts of labour so that they can club together and provide him with a suit of clothes in place of the rags he has to stand in. Poverty, insurgency, discontent, were on the doorstep of Edgworthstown House. Maria concludes her letter by remarking that her father would have been proud to see the family applying the principles of generosity, care and educational improvement he took seriously as his duty of landowning care. Maria may in fact be gently mocking ‘proofs’ of value in external marks of ‘breeding’ and the tendency to translate them from the animal kingdom to the human. Certainly the particular brand of benevolent patriarchalism the Edgeworths wielded over their tenants as Anglo-Irish landowners feels uncomfortable and condescending to modern readers. But Maria is sharp and funny enough often to see those contradictions and make room for them in her letters. And in the end, her beloved doggo, bred by a man whom she greatly admired, was naturally the best pupperino in all of Ireland.

– Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull

Footnotes

1. Lovell established a remarkable co-educational school for one hundred and twenty Protestant and Catholic boys in Edgeworthstown based on his father’s theories of education in 1816. Before closing in 1833, the school attracted notable literary visitors including William Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott. For more, see Brian W. Taylor, ‘Richard Lovell Edgeworth’, The Irish Journal of Education (1986) XX: 1, pp.27-50.

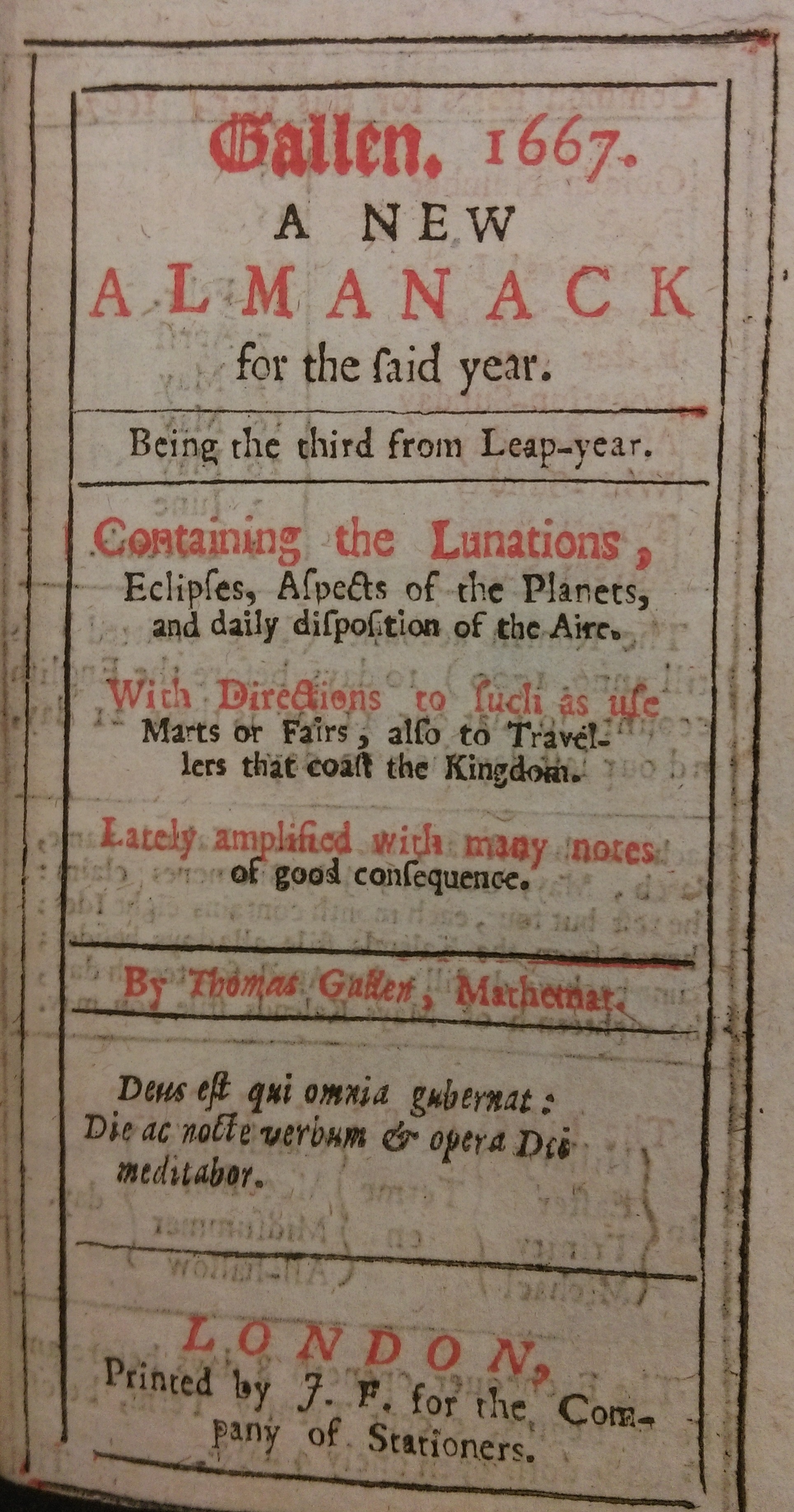

f a rare book (we have traced a handful of Gallen almanacs in the Bodleian, and none for 1667), has become a unique manuscript as it contains a diary of Jeffrey (or Jefferay) Boys of Betteshanger, Kent for the year 1667. The

f a rare book (we have traced a handful of Gallen almanacs in the Bodleian, and none for 1667), has become a unique manuscript as it contains a diary of Jeffrey (or Jefferay) Boys of Betteshanger, Kent for the year 1667. The