The little girl of the Kirātas, she the little one, digs a remedy, with golden shovels, upon the ridges of the mountains.

(Atharva Veda X.4.14, trans. Whitney, 1905)

Introduction

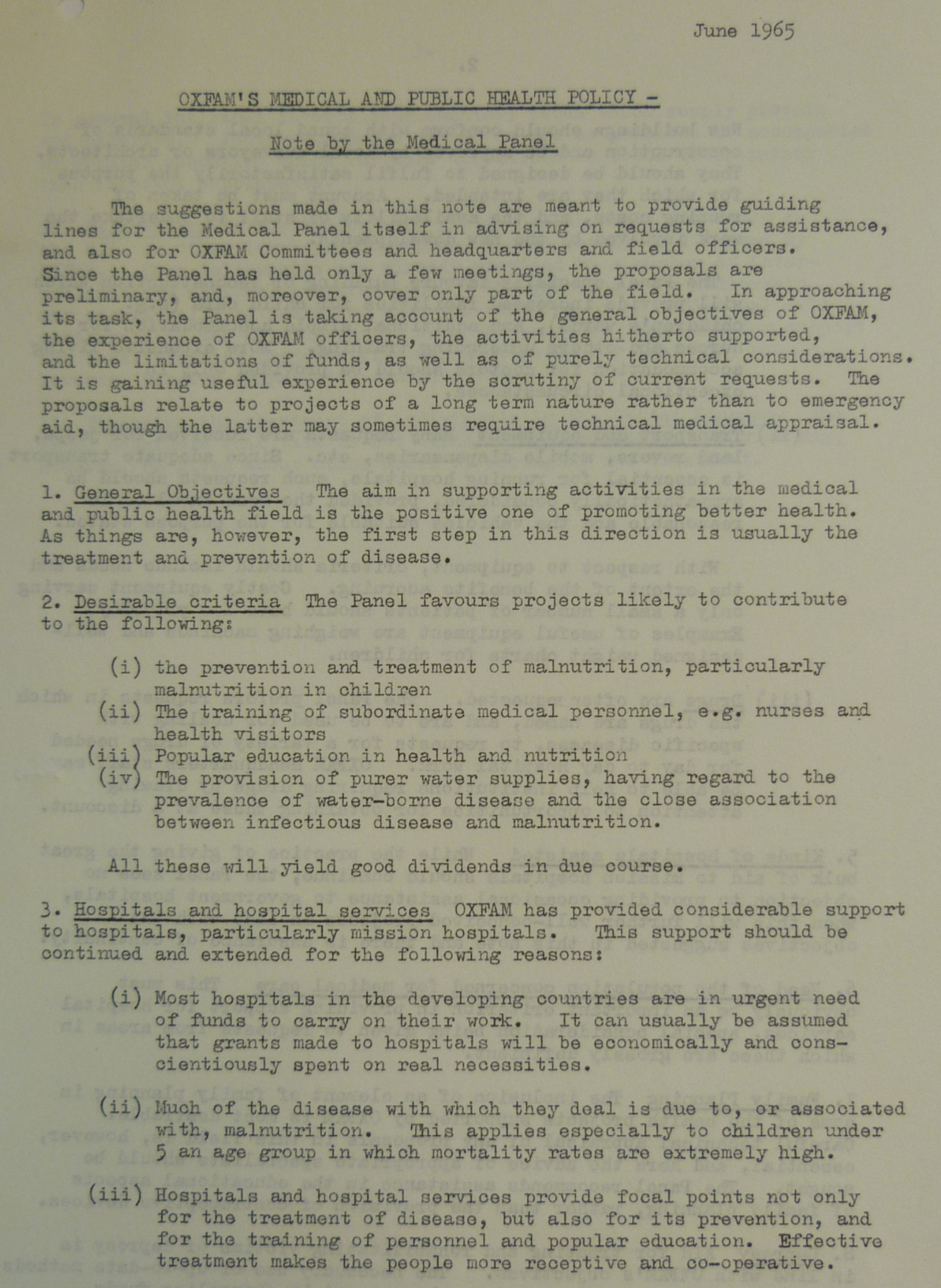

During the first phase of the Oxfam archive project the team will be appraising and cataloguing ‘project files’ relating to grant support from Oxfam for work in India. Before appraisal, approximately half of the 10,000 boxes in the archive fall under the category of ‘project files’, so it is going to be a mammoth task! The project files contain a wealth of information and will be an invaluable resource for researchers interested in a variety of countries and subject areas.

One project file that has initially caught my attention contains material relating to a grant for the ‘Tribal Medicine Project’ approved on 21 June 1988, which will be the focus of the next 2 posts. The description of the project is as follows: ‘To support additional work in final 3rd phases of a study on tribal medicine […] to train tribal youth in their own health care system; to encourage tribal’s to plant and cherish medicinal plants – for their use and probably also income generating.’ This was a surprising discovery, and reiterated the huge range of projects that Oxfam has funded and been involved with. The projects span categories such as health, agriculture, social organisation, education and humanitarian emergencies.

The Tribal Medicine Project’ (Oxfam reference BIH 091/Q8) was carried out by the Rural Development Association (RDA) in Bihar, in north-east of India. Oxfam has been working in this region since 1951 when a famine in Bihar prompted them to respond to a natural disaster in a ‘developing country’ for the first time. Oxfam awarded the RDA a grant of £3,008 which, in 1988, equated to 74,000 Rupees. This was just one of many grants that Oxfam made to them for a variety of projects.

|

| Cash receipt for the first installment (Bodleian Libraries, Oxfam Archive) |

From the documentation, we know that the principal project investigator was Dr. Kali Krishna Chatterjee. In a detailed summary report written by Chatterjee there is statistical information, such as how many practising ‘tribal medicine men and women’ there were and how many ailments they could treat, as well as information about the efficacy of herbal medicines on particular diseases and illnesses, ranging from malaria to respiratory infections and skin complaints.

Contained in this file there is also a letter addressed to David de Pury (Oxfam’s temporary representative for East India who was based in Calcutta) from the RDA’s Secretary Dipankar Dasgupta dated 15th April 1988. In this letter, Dasgupta mentions an ‘invitation to participate in the “International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences” to be held […] at Zagreb’ for both himself and Dr. Chatterjee. He writes:

This would give us an opportunity to bring into international prominence the rich tradition and prospect of developing tribal medicine as an alternative form of medical culture which will help the poor people to come out from the clutches of the present dominating modern system of medicine.

The letter asks Oxfam to contribute to their travel expenses, and they clearly both attended as their presentations are listed in Abstracts: 12th International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, Zagreb, 24-31 July 1988. We also know, from a budget submitted with the project application, that two anthropologists were employed on the project.

The OED defines ethnobotany as: ‘The traditional knowledge and customs of a people concerning plants; the scientific study or description of such knowledge and customs’. This includes the medical uses of plants, and I think it aptly describes the remit of theTribal Medicine Project.

In an appendix to Dr. Chatterjee’s summary report, the history of Indian traditional medicine is traced back to the ‘Ayurvedic’ system. Ayurvedais the system of traditional medicine native to the Indian subcontinent and a form of alternative medicine. Dr. Chatterjee ends this appendix with a quote, cited in full above, ‘about a Kirāta girl collecting herbal medicines from the ridges of a mountain’. This passage is from the Atharva Veda (or Atharvaveda), one of the four Sanskrit Vedic texts originating from ancient India.

|

| MS. Mill 80 Atharva-Veda Samhitā, c. 1840 (Bodleian Libraries, Oriental Manuscripts) |

Most importantly in this context, the Atharva Veda is ‘intimately connected to the medical traditions of classical India, and it presents some of the earliest perspectives on the concept of diseases and how to cure them’. The ‘herbal medicines’ the Kirāta girl is collecting are for a remedy against snake bites. It is the 14th stanza of a longer passage about remedies which invoke the white horse of Pedu as it was known as a slayer of serpents. The reference to this classical India text demonstrates how the scientific study of the medical uses of plants can lead to, and arguably requires, a much broader investigation of the medical culture of the people concerned.

In the next blog post I will continue to look at the work of the Tribal Medicine Project in the broader context of Oxfam’s policy on traditional medicine…