It may be impossible to provide a comprehensive listing of resources in the Archive related to women and the Party, but following our previous posts we thought it might be useful to highlight some key areas and resources for users interested in the subject.

Key areas to investigate before suffrage include the Primrose League, trade organisations and other satellites of the Party. After 1918, the Women’s Unionist Organisation (later the Women’s National Advisory Committee in various manifestations) handled a great deal of educational and canvassing issues; it also organised an annual Women’s Conference. The majority of this material is held in CCO 170, including:

- Minutes, 1935-1965 [CCO 170/1]

- General Purposes Committee minutes, 1944-1951 [CCO 170/1]

- Outside Organisations Subcommittee minutes, 1944-1977 [CCO 170/1]

- Parliamentary Subcommittee minutes, 1946-1948 [CCO 170/1]

- Annual Conference handbooks, 1939-1991 [CCO 170/3]

- Other papers, c1928-1986 [CCO 170]

There is also some information in the area files relating to individual committees Area level records:

- Greater London: Minutes, 1966-1986 [ARE 1/11]

- North West Minutes, 1933-1953 [ARE 3/11]

- Midland: Minutes, 1887-1890; 1947 [ARE MU 11]

- West Midlands: Minutes, 1925-1982 [ARE 6/11]

- Eastern: Minutes, 1920-1984 [ARE 7/11]

- South East: Minutes, 1920-1976 [ARE 9/11]

- Wessex: Minutes, 1920-1962 [ARE 11/11]

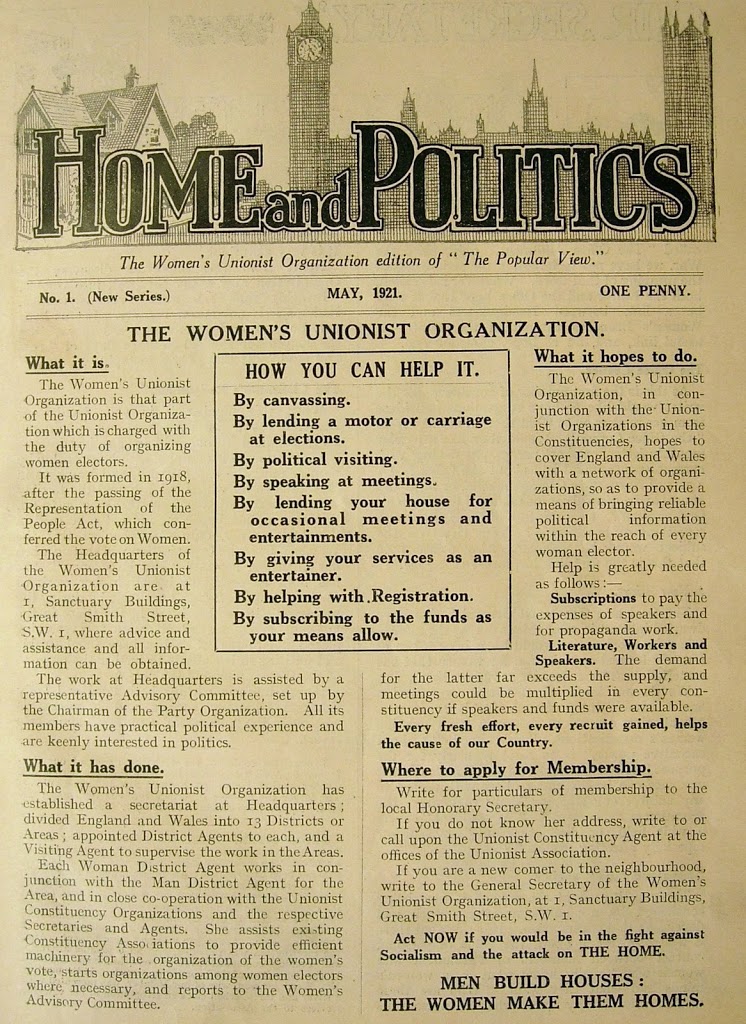

As mentioned previously, the WUO/WNAC was responsible for a number of publications, some of which are available in the CPA:

- Home & Politics, 1922-1929 [PUB 212]

- Home Truths, 1949-1951 [PUB 146]

- Madam Chairman, 1957-1966 [PUB 136]

- Onward (with a ‘lady’s page’), 1953-57 [PUB 215]

Some material is held elsewhere in the Archive, among the papers of other committees or meetings:

- Organisation Department papers on the WNAC, 1946-1968 [CCO 500/9]

- Chairman’s Office papers on women’s organisations/conference, 1962-1971 [CCO 20/36]

- Various files in the CCO Filing Registry, 1948-1975 [CCO 4]

A few other individual files may also be useful. PUB 244 has now been created for women’s organisation publications, and there are a handful among the publications of other groups. PUB 182/4, for instance, contains Hats Off! … to Conservative Women, by Elizabeth Hodder (1990). CCO 500/1/5, Chamberlain’s reports on CCO reorganisation, mentions the Women’s Department and the changes to women’s organising (1930s). The Conservative Agents’ Journal [PUB 2-13] can be trawled for its various references to women’s roles in the Party.

The papers of Lady Emmet and Lady Young, although not contained in their entirety within the CPA, are also particularly illustrative of a Tory woman’s career. Some of Lady Emmet’s papers are contained within those of the International Department (CCO 507) and Lady Young’s within CCO 60 (uncatalogued). Further collections of Lady Emmet’s papers can be found in the Bodleian via the Special Collections Reading Room.

Of course, there are many other resources, both within the Bodleian Libraries and without, that may help researchers in women’s history in the Conservative Party. A quick search on SOLO (our catalogue tool) for ‘women “conservative party”’ turns up 48 items. And although their material is often designed with school curricula in mind, the National Archives have some particularly interesting document links on their education pages.

If you have any questions about our material, or indeed think we’ve missed anything in this short guide, do get in touch with us; click on the ‘About Me’ tab to access our email information.