Today I discovered exactly how compulsive family history research can be when I went down a census rabbit hole after finding records of what appeared to be a female blacksmith in the Bodleian’s archival collections.

The Bodleian holds the Barham family papers which came here with the extensive Clarendon family archive thanks to Lady Katherine, the Countess of Clarendon (1810-1874), who married the 4th Earl after the death of her first husband John Foster Barham, a Member of Parliament for the rotten borough of Stockbridge in Hampshire and the son of Joseph Foster Barham, a prominent Pembrokeshire landowner who also owned substantial numbers of slaves in Jamaica. [You can find slave inventories and estate accounts in the Barham Family Papers.]

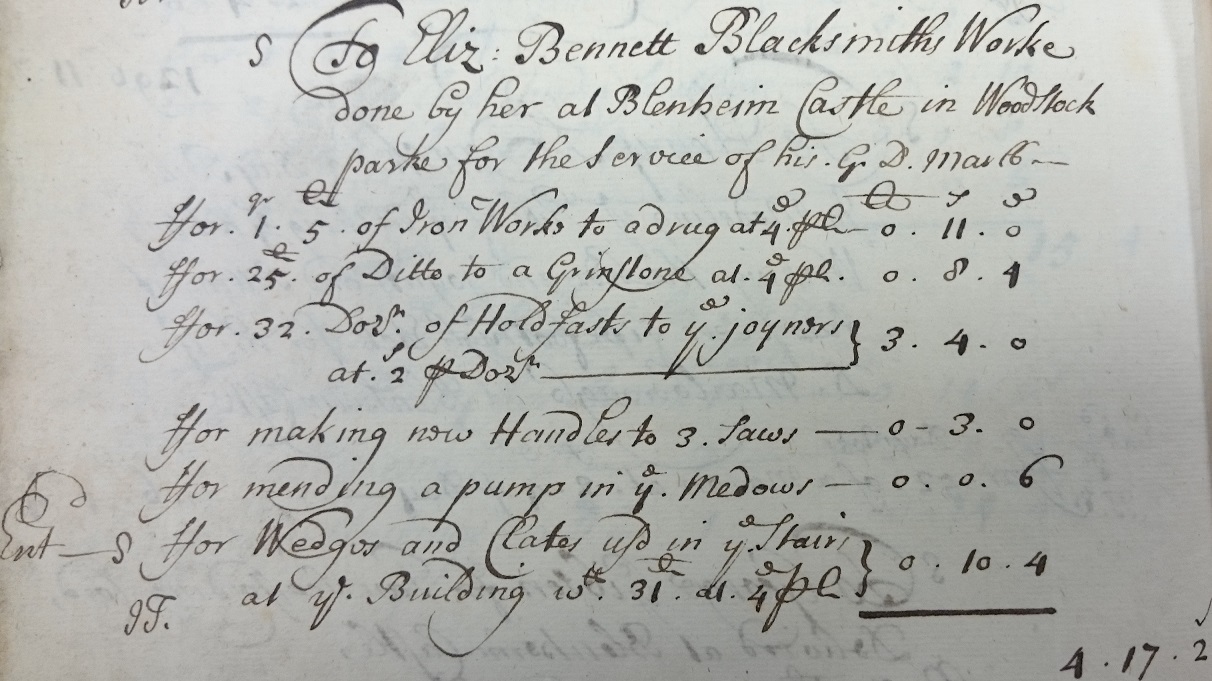

Top half of a bill for blacksmithing costs owed by William Barham to Mary Hulbert, 1834, Clarendon Archive (Earls of the 2nd Creation), Bodleian Libraries [click to enlarge]

Having learned five years ago that a woman smith worked on Blenheim Palace in 1708, I was particularly interested in the identity of this blacksmith: Mary Hulbert.

A plain search for Mary Hulbert on Ancestry produced a haystack’s worth of results, but I took a punt on the Stockbridge connection, and found that there was, indeed, a Mary Hulbert listed in the 1841 census in Stockbridge and that the Hulbert family included a blacksmith. But disappointing my hopes that she would be labelled a blacksmith in her own right, that blacksmith was her husband, George. And in fact, I soon found lower down the small stack of William Barham’s invoices (which include a bill for two nights away from home that tots up the cost of a bed, half a pint of best brandy, another bottle of brandy, and a bottle of gin) yet another 1834 blacksmith’s invoice, this one from…George Hulbert, also unpaid.

This was a useful reminder to always check related records before going down rabbit holes, but I was still curious about Mary Hulbert of Stockbridge, who, assuming she was the Mary Hulbert named on this invoice, was at the very least involved in her husband’s business. In fact, given that the jobs and dates on the two blacksmithing bills are different, it remains possible that Mary really was doing work on her own account, and more of it and at a greater value than George, whose bill only lists jobs on 29 May and 7 June 1834 worth the comparatively small sum of 4s 11d.

Interestingly, birth and marriage records show that Mary was 16 years older than her husband: he was 22 when they married in 1822, and she was 38. I wondered if perhaps Mary’s father had been a blacksmith and George Hulbert his apprentice, but in fact, no, a quick and dirty search suggests that her father Thomas Young was a maltster, while a 1784 Hampshire directory lists another George Hulbert as a blacksmith in Stockbridge, so it looks like smithing was the Hulbert family trade.

Although it seemed more than likely at this point, I still couldn’t be certain that the Mary and George Hulbert sending bills to William Barham were the Stockbridge Hulberts. I thought it would be worthwhile to have a look at William Barham’s records to see if he had a direct connection with the town, given that he himself was never Stockbridge’s MP.

And that’s where things got intriguing.