by Alexandra Turney

Apollo as a shepherd in Austria; Dionysus as a priest in medieval France; Aphrodite as a child washed up on the coast of Italy. While the Ancient Greeks and Romans wrote of the glory of their gods, some 19th century writers were more inspired by the idea of their fall from glory, and descent into obscurity. What kind of life would a pagan god live in modern, Christian Europe? How would they cope with their anonymous existence? And there’s another question, which I’ve recently been asking myself – why are so we fascinated by the idea of the gods in exile?

The German poet Heinrich Heine was one of the first to imagine the reincarnated gods, writing about them with mingled emotions of awe and pity (and a touch of irony) in his essay ‘Gods in Exile’:

The [Church] by no means declared the ancient gods to be myths, inventions of falsehood and error, as did the philosophers, but held them to be evil spirits, who, through the victory of Christ, had been hurled from the summit of their power, and now dragged along their miserable existences in the obscurity of dismantled temples or in enchanted groves, and by their diabolic arts, through lust and beauty, particularly through dancing and singing, lured to apostasy unsteadfast Christians who had lost their way in the forest….

Heine recounts various medieval legends about the gods, from Hermes living as a humble tradesman to an elderly Zeus weeping and shivering on a frozen island. “Decay is secretly undermining all that is great in the universe”, writes Heine, and rather than enjoying the spectacle, he advises that we should have some compassion for the fallen gods.

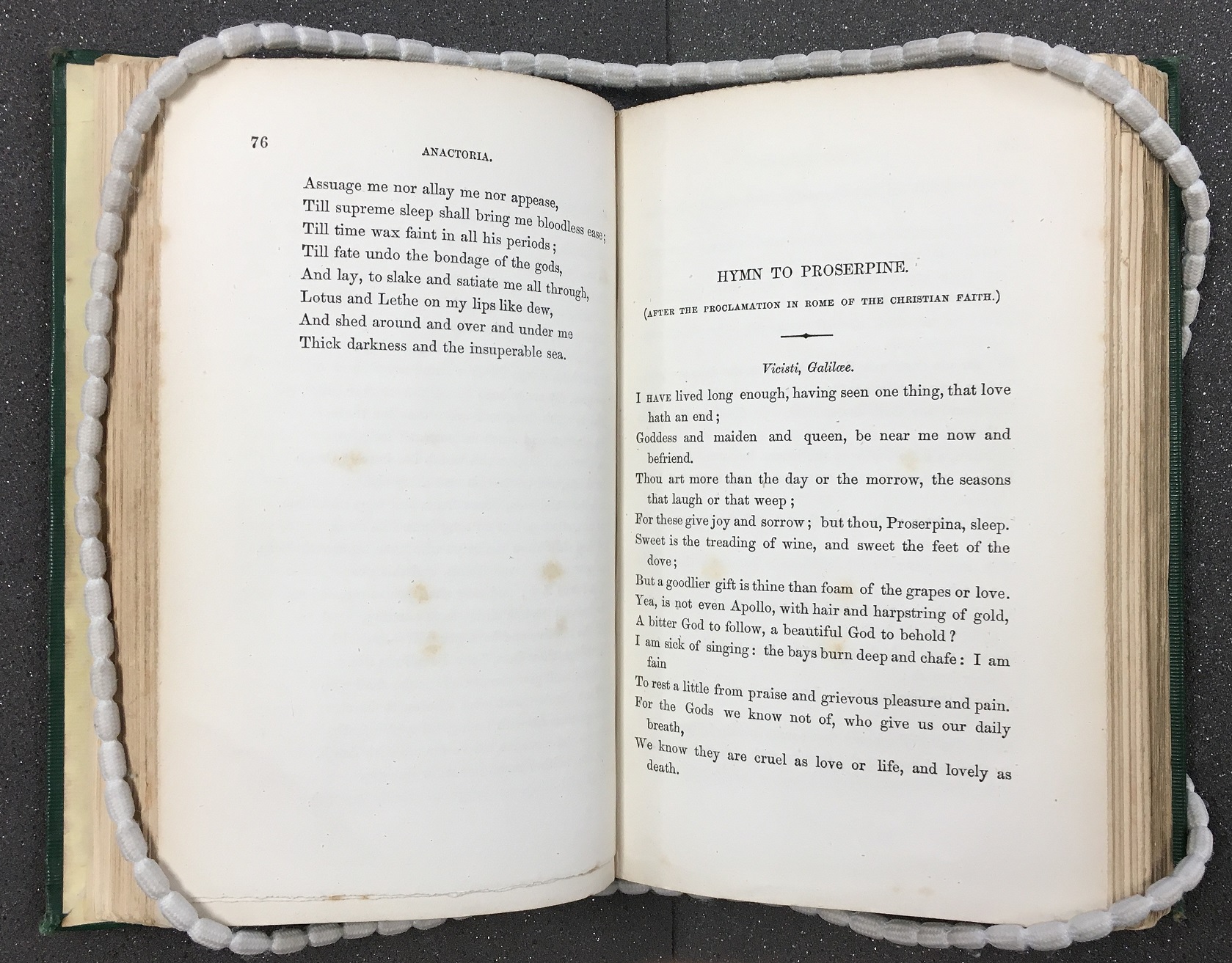

The idea of exiled gods was not a new one, but for some reason it captured the imagination of 19th century writers. In Swinburne’s poem ‘Hymn to Proserpine’ the speaker mourns his “Gods dethroned and deceased, cast forth, wiped out in a day”, while Walter Pater and Vernon Lee used short stories to explore the ideas from Heine’s essay in greater depth and psychological complexity.

Walter Pater has been remembered primarily for his art criticism – his meditations on the Mona Lisa and his famous line “To burn always with this hard gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.” His fiction, which includes the short stories of Imaginary Portraits, has been almost forgotten, but it contains some evocative contributions to the ‘gods in exile’ genre. ‘Apollo in Picardy’ and ‘Denys L’Auxerrois’ imagine Apollo and Dionysus in a medieval French context. In both stories, the gods are out of place in their Christian communities, and their conflict with their surroundings leads to tragedy.

Vernon Lee, whom Pater acknowledged as his “disciple”, saw connections between gods in exile and ghosts. In her essay ‘Dionysus in the Euganean Hills’ she suggests that the exile of the gods is “a kind of haunting; the gods who had it partaking of the nature of ghosts even more than all gods do, revenants as they are from other ages.” Her interest in the gods in exile was therefore an extension not only of her Hellenism and love of Italy, but also of her fascination with all things supernatural.

One of Lee’s best known short stories from Hauntings, ‘Dionea’, took direct inspiration from Heine. Venus (Aphrodite) is re-born in late 19th century Italy as a young girl of mysterious origins, who has an increasingly malignant influence on her surroundings. Male attempts to portray her or understand her are futile, leading only to disappointment, or even madness and death. Dionea may not be evil, but her influence is, and Lee suggests that this is a result of her alienation, and her incompatibility with the modern Christian world. The story ends with Dionea sailing away, “singing words in an unknown tongue”, unknowable to the last.

One of Lee’s best known short stories from Hauntings, ‘Dionea’, took direct inspiration from Heine. Venus (Aphrodite) is re-born in late 19th century Italy as a young girl of mysterious origins, who has an increasingly malignant influence on her surroundings. Male attempts to portray her or understand her are futile, leading only to disappointment, or even madness and death. Dionea may not be evil, but her influence is, and Lee suggests that this is a result of her alienation, and her incompatibility with the modern Christian world. The story ends with Dionea sailing away, “singing words in an unknown tongue”, unknowable to the last.

Just as the gods fell from glory, so the ‘gods in exile’ genre has faded into obscurity. I doubt I would have ever discovered these fascinating texts if I had not studied English Literature at Oxford, and attended lectures by Dr Stefano Evangelista in my first year as an undergraduate. I fell in love with the language of Swinburne, the ideas of Pater, the atmosphere of Lee.

Despite its strange, detached tone, one of the texts that made the greatest impression on me was Pater’s story ‘Denys L’Auxerrois’, a macabre tale about Dionysus’s unlikely career as a village priest in medieval France; it ends with ‘Denys’ being torn apart by the villagers in an act of sparagmos (ritual dismemberment). Ever since I studied The Bacchae at school I’d been fascinated by the figure of Dionysus – god of wine, divine ecstasy and ritual madness – and Pater’s tale of resurrection/destruction added an intriguing new chapter to the god’s mythology.

Several years later, living in Rome and daydreaming on the metro on the way to work, I found myself thinking of ‘Denys L’Auxerrois’ and Dionysus. What would happen if the god were re-born in modern Rome, a city where he has no believers? I imagined him waking up in the Protestant Cemetery and gazing uncomprehendingly at the Pyramid of Cestius. As he slowly comes to consciousness he realises, to his disappointment, that he is alive again.

My metro daydream eventually became my debut novel, In Exile. I like to think of it as a resurrection not only of Dionysus, but also of the ‘gods in exile’ genre. While I’m aware that other writers have imagined the Greek gods in modern settings (such as Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson novels or Gods Behaving Badly by Marie Phillips), I was interested in exploring the melancholy, malevolent side of the gods, and the idea of exile. It seems to me such a fascinating concept, and a rich source of inspiration.

My metro daydream eventually became my debut novel, In Exile. I like to think of it as a resurrection not only of Dionysus, but also of the ‘gods in exile’ genre. While I’m aware that other writers have imagined the Greek gods in modern settings (such as Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson novels or Gods Behaving Badly by Marie Phillips), I was interested in exploring the melancholy, malevolent side of the gods, and the idea of exile. It seems to me such a fascinating concept, and a rich source of inspiration.

Aside from the glamour of the gods – centuries of art and literature are a testament to their continual fascination – I think there are two main explanations for the allure of the gods in exile. Pater and Lee are just two of many writers (and readers) who are obsessed with the past. It’s not so much a disdain for modernity as a fascination with the imaginative potential of the past, and the awareness that the past is at once unknowable and unavoidable. For Lee it is a continual, physical presence, a “borderland” that overlaps with the present. When we imagine a pagan god walking among us, we have the tantalising illusion of being able to understand these “revenants” from the ancient world.

But I think the ‘gods in exile’ genre has even wider appeal. Even more common and relatable than the obsession with the past is the interest in isolation and alienation. It’s a theme that can be found in practically every text ever written, from Beowulf to Twilight. Writers love to write stories about characters who feel out of place in their surroundings, and readers love to read about them.

At a glance, the ‘gods in exile’ genre might seem obscure and inaccessible. Why would the average modern reader, with only the vaguest notions of ancient religion and mythology, care about Dionysus’s reluctant resurrection? By writing In Exile, I hope I’ve answered the question. On some level Dionysus is not just a pagan god, but also Heathcliff or Holden Caulfield, or even the reader. In other words, god or human, author or reader, we have all felt like outsiders at some point in our lives. Exile can be a place or a time, but it’s also a state of mind.

Alexandra Turney is a graduate of St Catherine’s College, Oxford, and her novel In Exile was published in January 2019.