An alternative approach to colour wood engraving was chromolithography, which became the main means of producing coloured advertising after the introduction of machine printing in the late 1860s. The design was drawn by a team of artists on a set of stones (later plates), each one devoted to a particular colour and parts of the image. These colours were then printed one after another so that they blended visually. The variety of lithographic markmaking and the far greater number of colours used (often 8 to 15 in advertising) meant that the end product could be richer and more subtle than a colour wood engraving. In this print the colours are shown separately in the margin.

![Adams’s Furniture polish, [c. 1900], [1 p.], 202 x 326 mm. Ten-colour chromolithography with colour tablets](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/jjcoll/wp-content/uploads/sites/176/2020/05/Adams-chromolithograph.jpg)

As many as fifteen hues (ten in this case), printed from as many different stones, were routinely used by advertisers. This proof, still displaying its set of colour tablets, uses stippled dots to fuse the colours.

Like ‘ephemera’, the term ‘chromolithography’ is perhaps off-putting. Both terms represent, however, items that are both familiar and immediately appealing.

Chromolithography is a magical process, resulting in (at best) beautiful images in colour, the richness of which results from the successive layers of colours and tones inherent in their printing.

Chromolithography was anything but simple: large, sometimes huge, slabs of stone had to be quarried (usually in Bavaria) and transported. The stones had to be prepared for printing. The desired image had to be divided into its component colours and tones for printing, each on a separate stone. All needed perfect registration. It is almost miraculous that it worked, never mind that it became commercially viable. The (rare) surviving key-line drawings and ‘progressives’ are crucial to understanding the process. Although two colours are combined on each card, the Liebig series of collectable cards devoted to the creation of a twelve-colour chromolithograph shows something of its complexity. We have this series, from 1906, in Italian.

Around 1,881 series of Liebig cards were produced in several languages from 1872 to 1975, with some isolated later series in the 1990s and early 2000s.

It has been a privilege to benefit from the expertise of the world authority on lithography and chromolithography, Michael Twyman, who has identified the printing processes of all the exhibits in ‘The Art of Advertising’ including the number of colours in the (high proportion of) chromolithographs. These analyses are available through the image captions in the online version of the exhibition and give an insight into typical practices of the time.

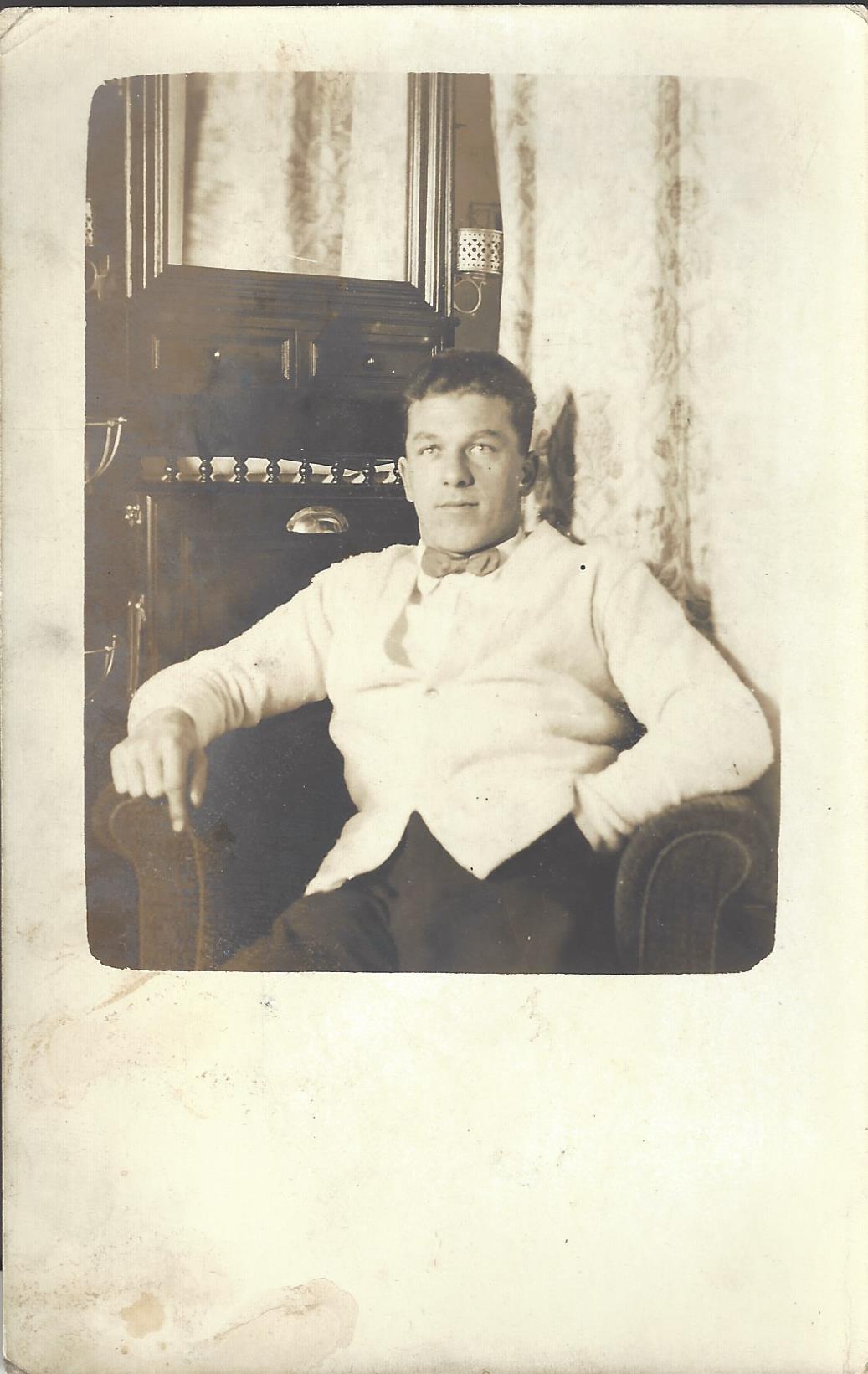

![S.S. Euripides. First Eng[ineer]](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/jjcoll/wp-content/uploads/sites/176/2020/05/Figure-6-1st-Eng-name-illegible.jpg)

![“My Queen” Vel-Vel, Felstead & Hunt, London and Manchester, [1887], [1 p.], 258 x 194 mm. Letterpress with wood engraving on coloured paper. J](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/jjcoll/wp-content/uploads/sites/176/2020/05/Womens-Clothes-and-Millinery-3-7-resized.jpg)