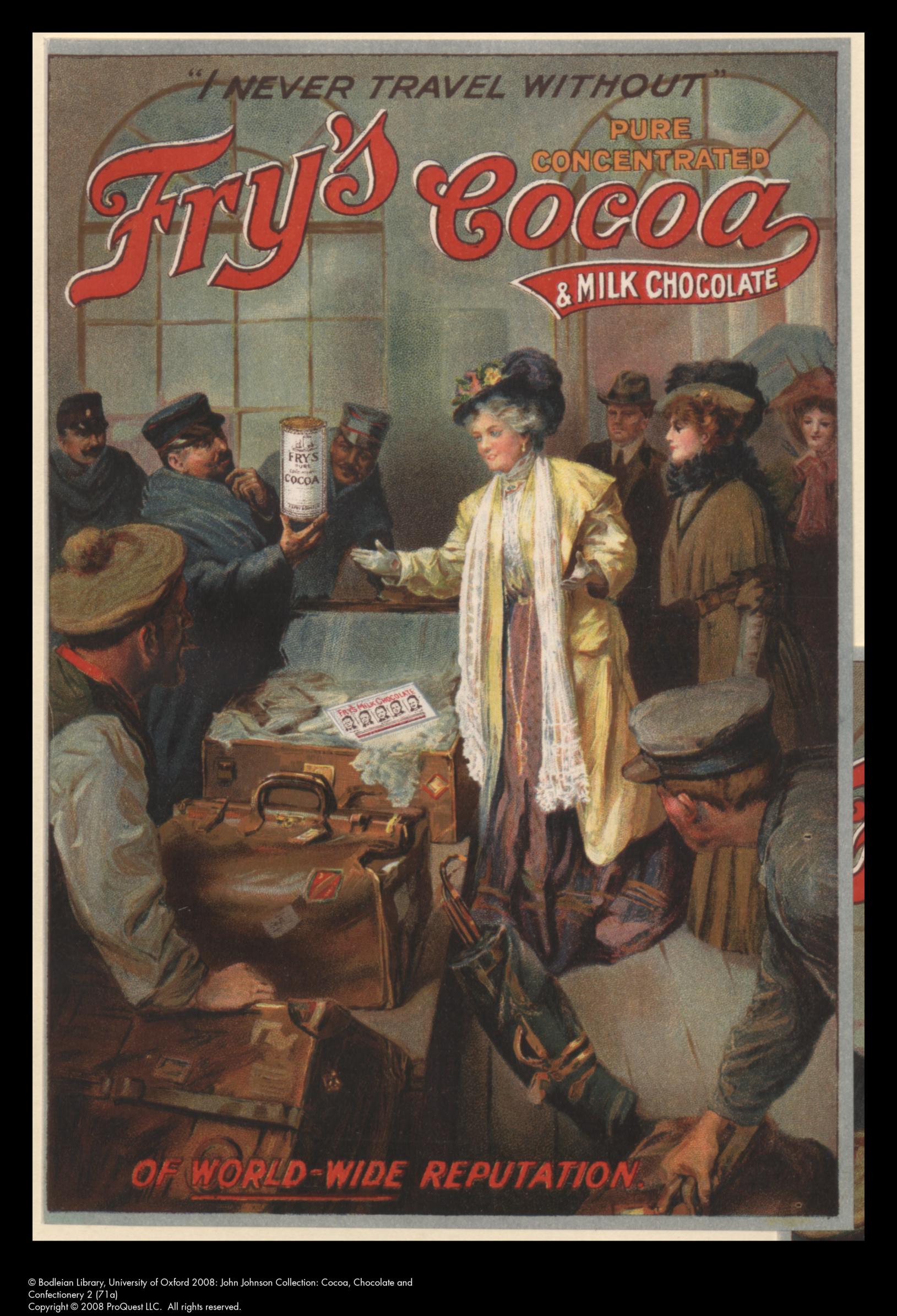

This seasonal blog post is based in part on exhibits in The Art of Advertising exhibition (figures 3, 4, 6, 8).

Certain products stand out for the competitiveness of their advertising. Lotteries and soap are obvious examples. The marketing of cocoa and chocolate, although less innovative, was prolific. It is in striking contrast with the perception of chocolate in our own time.

The earliest cocoa advertisement in the John Johnson Collection is a handbill produced by Anna Fry (between 1787, the death of her husband and her own death in 1803). Joseph Fry had taken over Churchman’s patent (the first in England, 1729) in 1761. It contains elements common to cocoa advertising for decades, especially claims of health benefits (often with medical testimonials).

This Cocoa is recommended by the most eminent of the Faculty, in preference to every other kind of breakfast, to such who have tender habits, decayed health, weak lungs, or scorbutic tendencies, being easy of digestion, affording a fine and light nourishment, and greatly correcting the sharp humours in the constitution.

Advertisements and labels for cocoa often also included directions as to how to prepare the beverage.

Until the 1850s, cocoa was consumed solely as a beverage.

For decades after that, until ways were found of adding less expensive ingredients to cocoa, it was marketed to the rich, as exemplified by two of the items in our exhibition The Art of Advertising.

However, rather than the self- indulgence that forms the major selling point of chocolate today, the emphasis was on the health benefits.

This Cadbury’s advertisement (fig. 4) is fascinating, not only in showing the benefits of cocoa to all ages (by implication of a certain class: the nursemaid seems to be excluded from partaking of the beverage) but for the scientific table showing the comparative value of foods. Here, Cadbury’s cocoa is favorably compared with raw beef and mutton, eggs and white bread and, in the smaller print below the table, with some of the best meat extracts. The terminology: Nitrogen (flesh forming!), Carbon (heat giving) is counter-intuitive to a modern viewer only too aware of the fattening effects of chocolate consumption and not attuned to the nutritional value of ‘pure’ cocoa.

Sweetness also became a selling point of chocolate, as in this F. Allen & Sons advertisement produced as a souvenir of the International Health Exhibition in 1884.

Another striking advertisement by F. Allen & Sons reminds us that cocoa was strongly associated with the Temperance movement in Britain. The inclusion of an image of a family in abject poverty (due to the father consuming liquor) is shocking, as it was meant to be. The implication that it was within the power of the family to elevate themselves out of poverty by buying cocoa instead is no less so.

Although filled Belgian chocolates date from 1912, the first chocolate bar was marketed by Joseph Fry & Son in 1847 and chocolates began to be sold in the 1850s. This J. S. Fry’s advertisement gives an idea of the range available in 1859. Fry’s are also credited with the creation of the first chocolate Easter egg in 1875.

In 1911, the contents of Rowntree’s Elect Coronation casket looked not dissimilar similar to chocolate selections today.