This year, the theme of Oxford Open Doors is extraordinary people. At The Law Library, w e have decided to take this opportunity to share some stories with you about the trailblazing women who fought for women’s status in the law profession. It is a small – but we believe important – supplement to the Women’s Suffrage in the UK our Official Papers colleagues are showing in the Law Library during Oxford Open Doors, as well as the Weston Library’s Sappho to Suffrage exhibition. (This last is open to the public until February 2019).

e have decided to take this opportunity to share some stories with you about the trailblazing women who fought for women’s status in the law profession. It is a small – but we believe important – supplement to the Women’s Suffrage in the UK our Official Papers colleagues are showing in the Law Library during Oxford Open Doors, as well as the Weston Library’s Sappho to Suffrage exhibition. (This last is open to the public until February 2019).

Even in the Bible, women were involved in the law. Take Deborah who was not only a wife but a prophet and a judge as well. Talk about a triple burden! Yet up until relatively recently, the English legal establishment did not readily admit women to the legal profession. In fact the initial women to study Law here at Oxford, weren’t even able to graduate. It wasn’t until October 1920 that women were actually allowed to be initiated as members of the university…although before this they were kindly allowed to pay fees. Obviously many women made a huge difference in the status of women within the legal profession. We have chosen just a few in order to show you the extraordinary people who studied Law here and how they changed the profession.

The first woman to study law at Oxford was Cornelia Sorabji in 1890[1]. She was born in India and was the first woman to graduate from Bombay University. After graduating, Cornelia was unable to qualify for a scholarship from the Indian Government to study abroad. The reason? Simple. She was a woman. Cornelia didn’t give up though and appealed for funds to allow her to study. She earned many supporters including, Florence Nightingale.

Cornelia wrote about her experiences in Oxford, seeming to truly revel in them but, there is an undercurrent of frustration at having to continually fight for her place. In 1892 Cornelia was the very first woman to take the Bachelor of Civil Laws exam. Though most people spent five years preparing for this exam, Cornelia spent only two. Still, she was devastated to receive a third. Her personal letters reveal that her supporters remained proud of her and encouraged her to keep going. Her friend and tutor Jowett spoke to the examiners who confirmed she had ‘curious powers of assimilation and a wonderful memory for case law’[2].

Eventually Cornelia returned to India. She was basically unable to practice law there. However, she saw that there was a genuine need within Indian society for a woman who was well versed in law. She took up the cause of the purdahnashins. These were secluded women who were forbidden from interacting with men. Since all the lawyers were men, these women had no access to legal help, making them incredibly vulnerable. Cornelia finally saw a place where her skills were urgently required. She became legal adviser to the British Government on the state of secluded women and during the next twenty years, she helped over 600 women and orphans[3].

Cornelia was eventually recognised as a lawyer in 1924, 34 years after taking her law exam! Despite the fact she was constantly told that her gender would and should prevent her from achieving her legal aspirations. Cornelia defied this to the very end, carving a place for herself in the legal world.

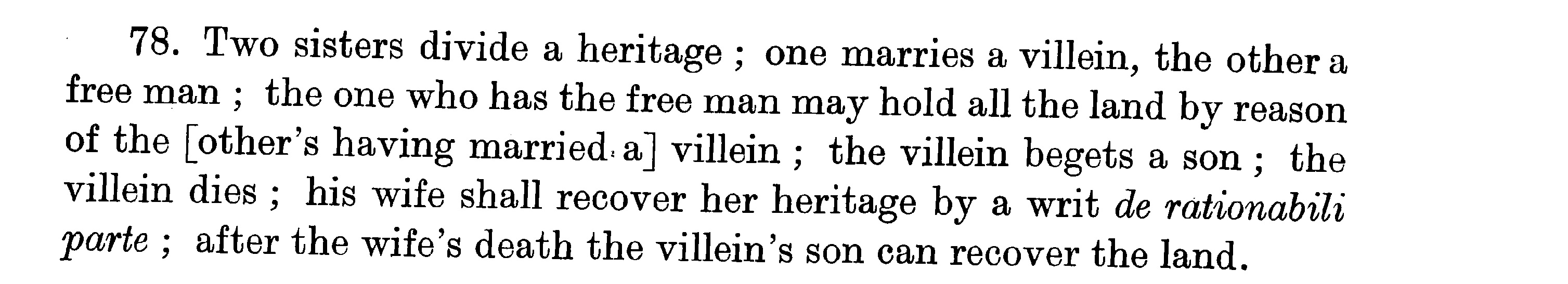

Gwyneth Bebb is our next trailblazer. In 1911, she was the first woman to achieve first class honours in her final law examinations. During this time period there was a movement to allow women into the solicitor’s profession. Gwyneth and three other women sent applications to take The Law Society’s preliminary examinations. They were all refused. Gwyneth and her associates brought actions against The Law Society. Their argument hinged on the fact they were ‘persons’ according to the Solicitor’s Act 1843.

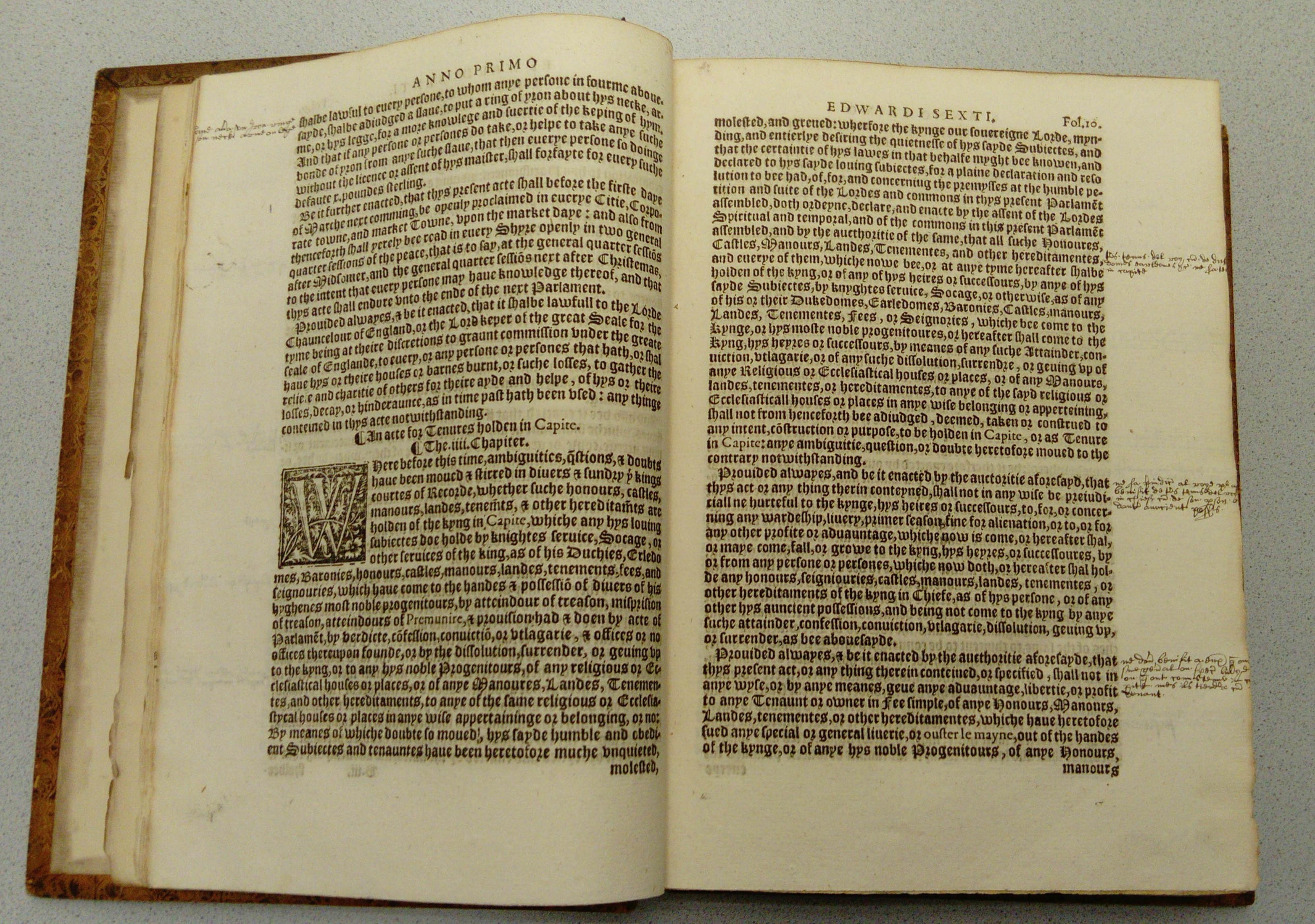

They lost the case. The reasons cited were that women have never been solicitors and therefore it was parliament who must decide. The judge, Cozens-Hardy could only provide one legal source that actively excluded women. This relied on Edward Coke, appointed Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in 1606 then in 1613 Chief Justice of the King’s Bench (so hugely influential), who approvingly referenced a 14th Century law textbook which stated:

“Fems ne poient estre attorneyes”

If you were a fan of our last blog post, this is a good chance to practice your law French… but for those who still need a little help, it says that women cannot be attorneys. The judge relied on this secondary source, The Mirror of Justices, even though today it is less venerated simply because of its antiquity than it was in Coke’s times. Despite admitting that Gwyneth in particular was ‘probably, far better than many…candidates’ the judge ruled that her intelligence and abilities had no bearing. She was a woman and therefore ineligible[4].

It would be easy to think that Gwyneth therefore was not a trailblazer. She lost. She never practised law. But you’d be wrong. As shown below, the media surrounding this case was intense.

The Daily Sketch, 11th December 1913, covering the appeal of Bebb v The Law Society. Picture from: https://www.facebook.com/first100years/photos/a.292102647607911/1009845759166926/?type=1&theater. Accessed 21 August 2018

On the 25th January 1913, The Express wrote, “If a woman can take a first class in law at Oxford, what right has the Law Society to prevent her from earning her living as a solicitor?”[5] Gwyneth brought the absurdity and injustice of the situation to the public eye. In 1919, parliament passed the Sex Disqualification (Removal Act). Women could no longer be excluded from a profession based on gender. Cases such as Bebb’s were instrumental in reflecting and influencing the changing public opinion about the place of women in the workforce.

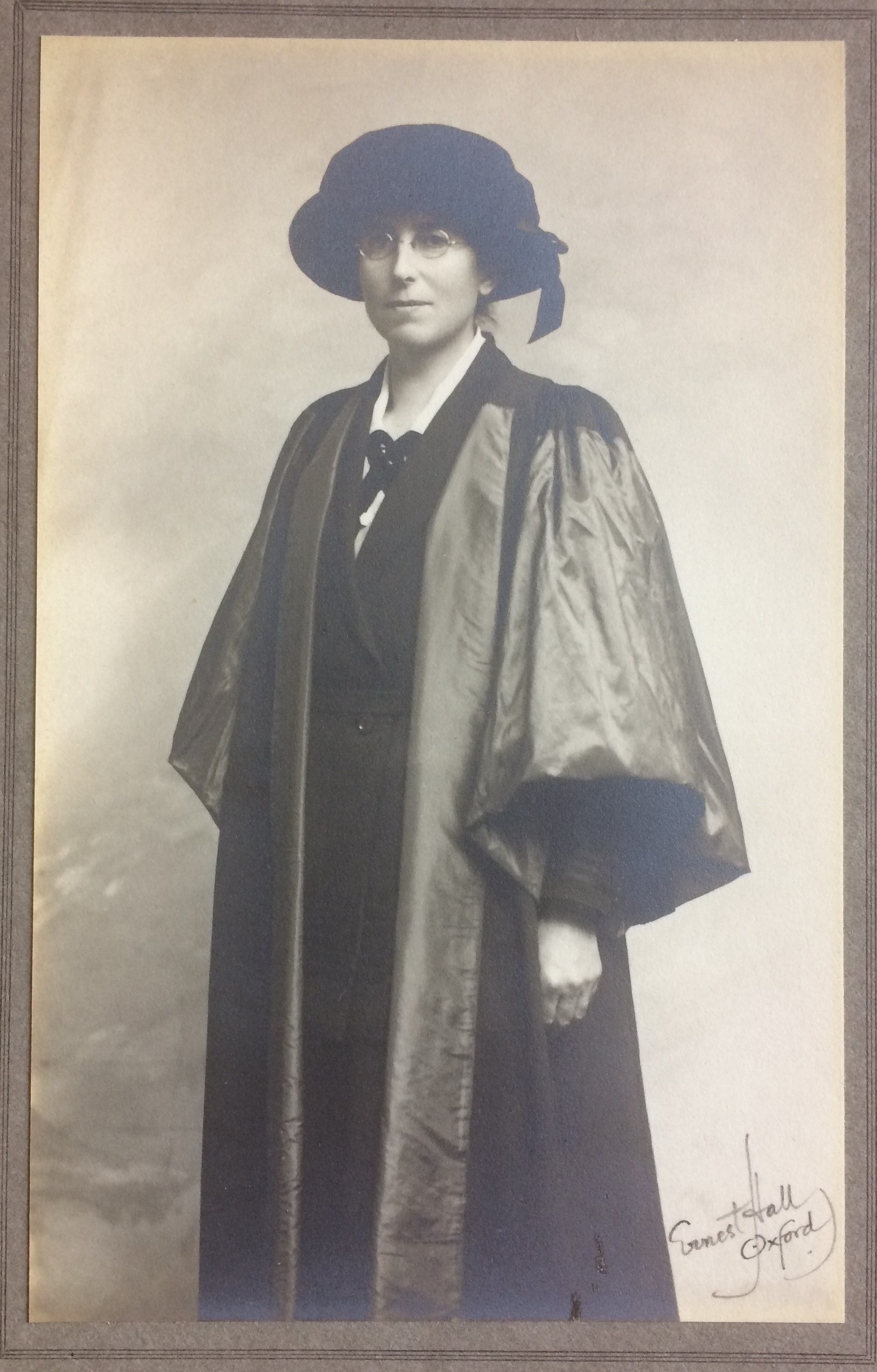

A few years after this act Ivy Williams was the first woman to be called to the English Bar and only a year later was the first woman be awarded the degree of Doctor of Civil Law in Oxford.

Ivy was another who was frustrated by women being forbidden to join the bar. She was frequently warned that ‘women would not succeed at the Bar because of the smallness of their voices and the prejudice of solicitors’.[6]

She was convinced that it would occur. As far back as 1904 she had stated that,

‘The legal profession will have to admit us in their own defence … a band of lady University lawyers will say to the Benchers and the Law Society ‘Admit us or we shall form a third branch of the profession and practice as outside lawyers’’[7]. The Law Journal saw this as a threat and a pretty empty one at that. Ivy finally joined the Inner Temple as a student in 1920 after the Sex Disqualification (Removal Act).

She described her appointment as ‘the dream of her life’[8]. Even in this moment she thought of furthering her cause by not only thanking the benchers but asking them to support the women who were sure to follow her. A petty person might have enjoyed The Law Journal’s swerve when they described Ivy’s call to the bar as ‘one of the most memorable days in the long annals of the legal profession’. Sadly even this statement was qualified by adding that the day “was never likely to be justified by any success they [women] will achieve in the field of advocacy.” Urgh!

Still none of this slowed Ivy down. Ivy taught law at Oxford making her the first woman to teach English law at an English university. She published The Swiss Civil Code: English Version, with Notes and Vocabulary which was well received by the Swiss federal authorities. In 1930 she was a delegate to The Hague conference for the Codification of International Law and in 1932 she was a member of the Aliens Deportation Advisory Committee. When she started to lose her eyesight, she learned Braille and then worked to help others learn it, prompting Miss Ruth Butler, former vice-principal of the Society of Oxford Home Students, to state in her obituary, that “She turned her necessity to glorious gain”, using in old age for the service of others her powers and enthusiasm which had won her distinction in her youth’.

I think we can definitely consider her trail well and truly blazed.

So I bet after all these female firsts you’re starting to wonder, ‘who was the first woman to work at the law faculty?’ That honour went to Elizabeth Ely. She read Law at St. Anne’s, won the Winter Williams scholarship (founded by Ivy Williams herself) and received a first. After taking the BCL at Oxford and the LL.M at Yale, she returned to St. Anne’s as a research fellow and elected fellow in 1958. She played a crucial role in helping St Anne’s get full collegiate status by redrafting the statutes to make them align with the statutes from the other four woman’s colleges. Sadly it’s hard to find much further detail on Elizabeth although St. Anne’s do say that ‘Her lively and charismatic personality left a strong impression on all who knew her[9].’ Despite a lack of detailed stories, we know she tutored many students between 1920 and 1945 and became a C.U.F lecturer in 1957 allowing her to contribute to the future of law, not only by being an example of a women succeeding but also by passing on the knowledge she had acquired to the next generation.

My last trailblazer is Ann Smart. Ann read Jurisprudence at St. Anne’s and graduated with a first. She was another winner of the Winter Williams scholarship. Ann was the first woman lecturer at Magdalen and the first law fellow appointed at St. Hugh’s. She went on to found the College Law Society with Edward Burn and Derek Wood. As the Faculty Representative for the Bodleian Law Library she was able to further influence the teaching of law here. She also created the second law fellowship at St. Hugh’s, now called the Ann Smart fellowship. Since Ann was the second woman to gain a double first in both her undergrad and her BCL, it might be unsurprisingly that she went on to do so much and garner such respect. What is pleasantly surprising is how much energy she pumped into helping the next generation of lawyers. Like Ivy, with her scholarship, like Elizabeth, with her teaching and with her own commitment to the law School of St. Hugh’s which she has built from scratch, Ann has helped provide a strong environment for students to receive their education in law[10].

So since we had all these trail blazers working on it for years, the path for women must be perfectly clear, right? It’s a bit of a mix, to be honest. If you look at statistics women now make up 48% of lawyers in law firms. That’s basically half. Job done!

Unfortunately as we move to senior levels the numbers change a bit. In 2017 women made up 59% of non-partner solicitors compared to just 33% of partners. It’s only fair to note this is actually an increase, albeit a small one, from the figures in 2014[11].

So how can we try and even this out? First of all there are organisations such as Oxford Women in Law (OWL), a network to allow graduates from Oxford to meet, share experiences and discuss career issues. They hold workshops, invite guest speakers and try to provide a supportive environment.

So how can we try and even this out? First of all there are organisations such as Oxford Women in Law (OWL), a network to allow graduates from Oxford to meet, share experiences and discuss career issues. They hold workshops, invite guest speakers and try to provide a supportive environment.

Also our final lawyer from our display, Christina Blacklaws has recently been inaugurated as the 174th president of the Law Society of England and Wales. She is the first woman from Oxford to achieve this honour. One of the main aspects she wants to focus on is gender equality. She has therefore launched a how-to guide for round tables investigating gender inequality, of which more than 100 will be held nationally and internationally, with the results of the research scheduled for publication in spring 2019.

These movements towards gender equality are encouraging. Recent news such as the appointment of a third female justice to the UK Supreme Court in June of this year reminds us that things are definitely moving in the right direction, even if things are still not equal. Cruickshank felt we might feel ‘we have achieved true equality when we no longer note when a woman lawyer is the first to’ do something[12]. I think even this might be a step away from true equality. It is great that Christina Blacklaws is president of the Law Society. However, every report of this I have found has highlighted that she is only the fifth woman to hold the post (most of them within the first sentence). Perhaps when people don’t feel it’s worth commenting whether the lawyer is male or female we can all feel equal. Until then, these statements of female success show us how far women have come. (Just think back to how lawyers considered it simpler to say women didn’t qualify as ‘people’ rather than to admit them to the bar!). But, perhaps more importantly, they also show there is always room for more trailblazers of all genders.

Have we missed anyone out? Are there any female lawyers with an Oxford connection that you think we should have mentioned? Or have you personal stories that you would like to share about women in the law profession who have inspired you? Please do let us know in the comments or via twitter.

[1] Joe Sommerlad, ‘How a Determined Young Woman Smashed Glass Ceilings to Become India’s First Female Lawyer’ (The Independent, 2017) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/cornelia-sorabji-india-female-lawyer-first-woman-google-doodle-feminism-oxford-university-a8055916.html> accessed 21 August 2018.

[2] (Opening doors, Paragraph 12.129)

[3] Jovita Aranha, ‘Here’s How India’s First Woman Lawyer, Cornelia Sorabji Opened Law For Women In 1924!’ (The Better India, 2017) <https://www.thebetterindia.com/115687/india-first-woman-lawyer-cornelia-sorabji/> accessed 21 August 2018.

[4] Jocelynne A Scutt, Women And Magna Carta (Palgrave Macmillan 2016).

[5] ‘Gwyneth Bebb | First 100 Years’ (First100years.org.uk) <https://first100years.org.uk/gwyneth-bebb-2/> accessed 21 August 2018.

[6]Hilary Heilbron, ‘Women At The Bar: An Historical Perspective | Counsel’ (Counselmagazine.co.uk) <https://www.counselmagazine.co.uk/articles/women-the-bar-historical-perspective> accessed 21 August 2018.

[7] ‘Dr. Ivy Williams’ (Museum-newtonabbot.org.uk) <http://www.museum-newtonabbot.org.uk/dr-ivy-williams> accessed 21 August 2018.

[8] ‘Ivy Williams | First 100 Years’ (First100years.org.uk) <https://first100years.org.uk/ivy-williams/> accessed 21 August 2018.

[9]‘St Anne’s College, Oxford > About The College > Elizabeth Ely’ (St-annes.ox.ac.uk) <http://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/about/history/founding-fellows/elizabeth-ely> accessed 21 August 2018.

[10]‘Ann Smart; Influential Law Tutor At Oxford Who Was The First Woman Lecturer At Magdalen And Who Later Taught At St Hugh’s For 23 Years’ (2010) April 1 The Times.

[11] ‘How Diverse Are Law Firms?’ (Sra.org.uk, 2017) <http://www.sra.org.uk/solicitors/diversity-toolkit/diverse-law-firms.page> accessed 21 August 2018.

[12] Elizabeth Cruickshank, Women In The Law (Law Society 2003).