On Tuesday 10 January, the Library’s Sheldon tapestry maps of Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire were cleaned as part of the initial phase of their restoration. Four of these tapestry maps were made for the former Weston House in south Warwickshire in or around 1590, the maps centred on Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire, all of which were able to feature Weston House, the home of Ralph Sheldon, who commissioned them.

The Bodleian owns a substantial part of what remains of the Gloucestershire tapestry, bought at auction in 2007; and Oxfordshire and Worcestershire, (both part of the 1809 Gough bequest). The Worcestershire tapestry hangs in Blackwell Hall, and was the first of the three to be treated by our colleagues from the National Trust. In October 2016, Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire were delivered to the National Trust’s textile conservation studio on the Blickling Estate in Norfolk, and from there preparation was made for cleaning.

The only facility large enough to clean tapestries of this size is at De Wit Royal Manufacturers in Mechelen, Belgium (halfway between Brussels and Antwerp), and so the tapestries were delivered in early January. De Wit’s team prepared the tapestries for cleaning on the previous day, so by the time we arrived to watch the process, Fig.1 shows pretty much what we saw, with everything laid out in a sealed chamber.

Fig.1: Awaiting cleaning – Gloucestershire in the foreground; Oxfordshire’s fragments beyond.

Cleaning began around 10am, as the chamber quickly filled with steam, and suction was applied from below. Before long, nothing could be seen inside the chamber, but De Wit had a camera in situ which moved across the tapestries, showing us absolutely everything at very high resolution on a screen in the “control area” next to the chamber. This procedure lasted over an hour, during which time we could monitor the liquid dropping down beneath the chamber, and samples of which were being collected in clear cylinders.

Fig.2: Cleaning over – the mist starts to recede.

With the cleaning phase completed, the De Wit team accessed a metal platform which moved on tracks above the tapestry. Fig.3 shows them rinsing the tapestries with hosed water and soft brushes. This process lasted around half an hour.

Fig.3: Rinsing the tapestries

Drying took place during the afternoon, beginning with large towels draped over the tapestries, that were then covered with plastic. This process took about five minutes, and was then repeated with fresh towels. Next, highly absorbent paper was used instead of towels, again compressed beneath plastic, and again repeated.

Fig.4: Applying the towels

To give some sort of impression as to the changing state of cleanliness of the tapestries, Fig.5 shows how the colour of the water emerging from the cleaning process. The cylinder on the left was the first to be collected, that on the right the last. Quite a contrast.

Fig.5: The tapestries are becoming ever cleaner

By 6pm we were able to enter the chamber to inspect at close hand the tapestries, checking the colours, and also being impressed at how dry they were. Fig.6 shows and area north-east of Oxford (towards modern Milton Keynes), and the colours are clearly stunning.

Fig.6 Cleaned, rinsed and dried

A fortnight later, we were able to travel to Norfolk and discuss how work might begin with our colleagues from the National Trust. The tapestries had been safely returned from Mechelen. Oxfordshire is planned to be the next tapestry to be displayed, and there are plenty of issues to contemplate, not least the number of gaps in the tapestry; its greater height and width than Worcestershire; and the question of whether we should incorporate a braid around the cartographic perimeter of the tapestry.

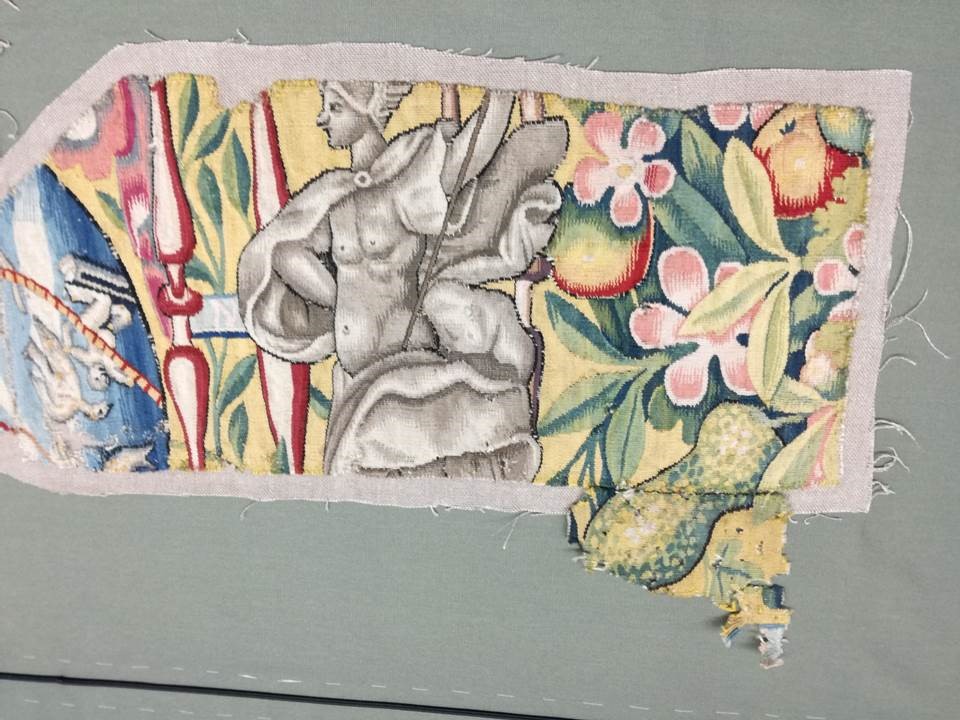

One major advancement however, concerned the status of six loose Gloucestershire fragments, which had not been sent to Belgium. Since the nineteenth century, it has been accepted that they belonged to Gloucestershire. On closer examination, we were able to conclusively prove that three of the six fragments are indeed part of Oxfordshire (see Figs 7 and 8). This was a terrific breakthrough.

Fig.7: One of the “Gloucestershire fragments” now attached to the top-right border of Oxfordshire

Fig.8: Another of the “Gloucestershire fragments” now attached to the upper border of Oxfordshire

During the day, we were also able to confirm all the place name details from Gloucestershire (which will need some serious restoration work to make them fully legible).

We are now looking at creating a plan for Oxfordshire: braid or no braid? how to deal with the damaged “globes” within the borders; how best to display the whole tapestry – the need for geographical compromise for the “island” that survives within the gap towards the north. For those unfamiliar with the Oxfordshire tapestry, you can rest assured that many places survive intact, not least Oxford and London, as well as Cheltenham and Swindon, and even the White Horse at Uffington, as well as much of the country west to Witney, Burford and beyond. When fully conserved the Oxfordshire Tapestry will replace the Worcestershire Tapestry on display in Blackwell Hall in the Weston Library

Fig. 9 The Worcestershire Tapestry in Blackwell Hall.

We look forward to updating colleagues as this exciting project develops. More news on the conservation work done on the Worcestershire Tapestry can be found here http://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/our-work/conservation/research-and-collaborations/sheldon-tapestry-maps/conservation-treatment