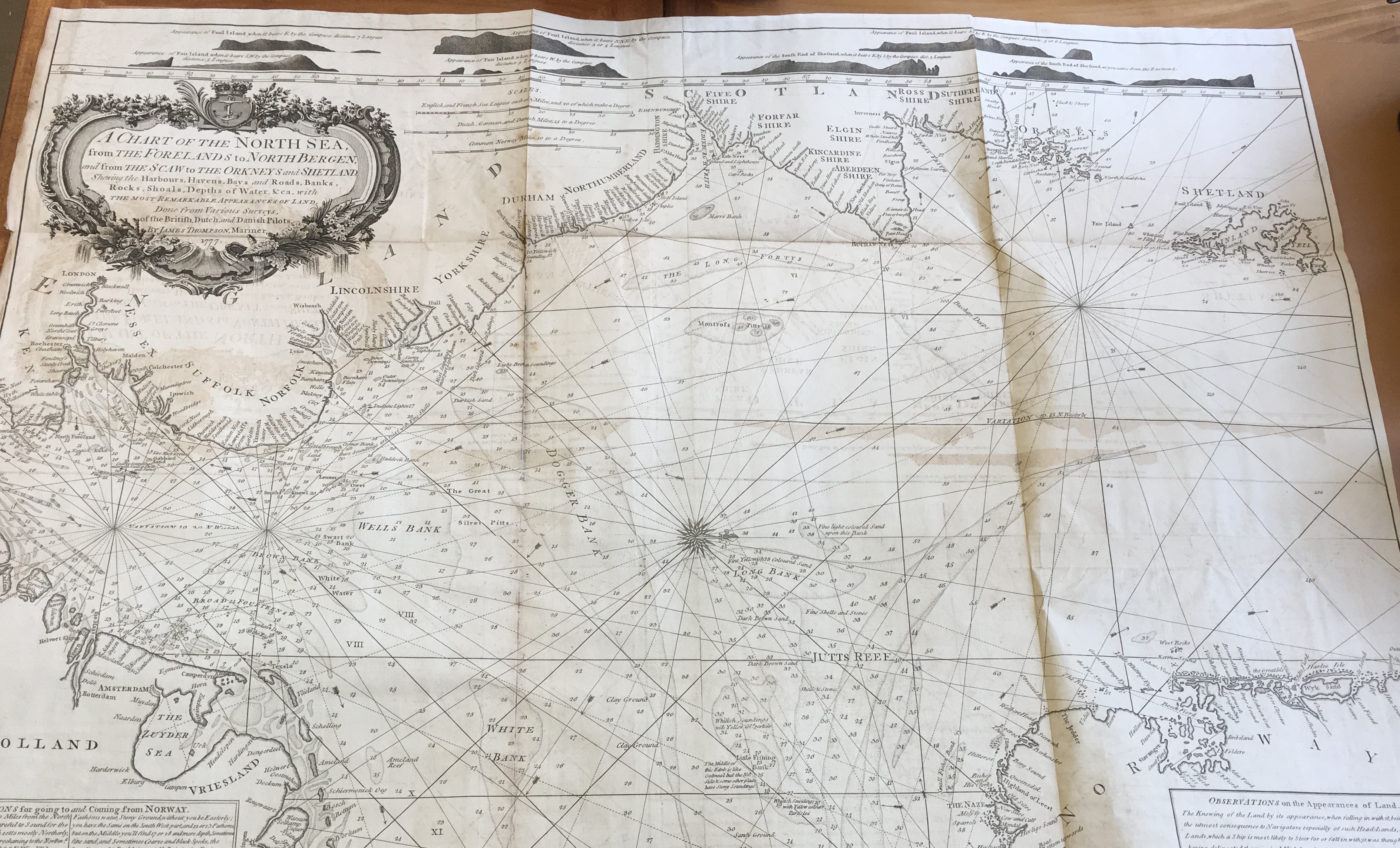

We are used to seeing maps a certain way; the land in detail with physical features described or shown and generally with north at the top. On my desk today is a map which turns all that on its head.  A chart of the North Sea from the Foreland S to North Bergen, and from the Scaw to the Orkneys and Shetland … By James Thompson, 1777

A chart of the North Sea from the Foreland S to North Bergen, and from the Scaw to the Orkneys and Shetland … By James Thompson, 1777

is a detailed sea chart concentrating on the features at sea, with the land barely getting a look in.

Much is made of the many sandbanks which litter this part of the North Sea with interesting reports, one even describing the Little Fishing Bank as ‘like oatmeal’.

Thompson has also includes several land profiles or “remarkable appearances of land” of coastal features and a descriptive panel to aid the seamen in their navigation. The presence of an identifiable building, such as a church or a distinctive geographical feature were as effective as signposts to mariners.

The other unusual thing about this chart is that for no obvious reason it is oriented with west at the top.

The other unusual thing about this chart is that for no obvious reason it is oriented with west at the top.

Not a lot is known about John Thompson apart from he described himself as ‘Mariner’ and so was most likely the captain of a vessel crossing the North Sea frequently enabling him the survey the area in such a detailed manner, as shown by the sheer number of soundings. This is in the same vein as Captain James Cook who was doing much the same thing in the Pacific at the time. It appears that this is Captain Thompson’s magnum opus and is found a small collection of seven charts by sea captains-hydrographers all published in the late 18th century, most by Robert Sayer and John Bennett in London.

A chart of the North Sea, from the Foreland S to North Bergen, and from the Scaw to the Orkneys and Shetland. [1777] (Vet.) 20122 a.13 (3)