The early 20th century was the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration with the competition between a handful of men really pushing the boundaries of discovery and survey. Ernest Shackleton was at the forefront of this but it wasn’t until after the Nimrod Expedition which he led from 1907 to 1909 that he was able to write about it.

The Expedition, named after the aging ship, Nimrod, was short on funds, lacking experience and preparations were rushed. Finally the difficulties were overcome and team were underway southwards. The main target was to be the first men to the South Pole. Once the team arrived in Antarctica there were a range of geographical and scientific objectives to be undertaken but there would be long periods of inactivity due to the season and weather. However, Shackleton had put some thought to what the team could do in the long dark winter months. He took along a printing press with which all the members of the Expedition wrote a book, Aurora Australis.

The challenges of writing, illustration, printing and binding this work in the frigid temperatures cannot be overstated and became the first book published in Antarctica. Published at ‘The Sign of the Penguin’ (Cape Royds) the extreme cold meant the printing ink became thick and difficult to work. It can be imagined that to include maps in this work would just be too difficult. However, about one hundred of these volumes were produced and bound by another expedition member, Bernard Day, using recycled horse harnesses and Venesta boards from the packing cases.

Each copy retains stenciling indicating the provisions packed in that case which gives each copy a name. The lettering on the Bodleian’s copy is “Kidneys”.

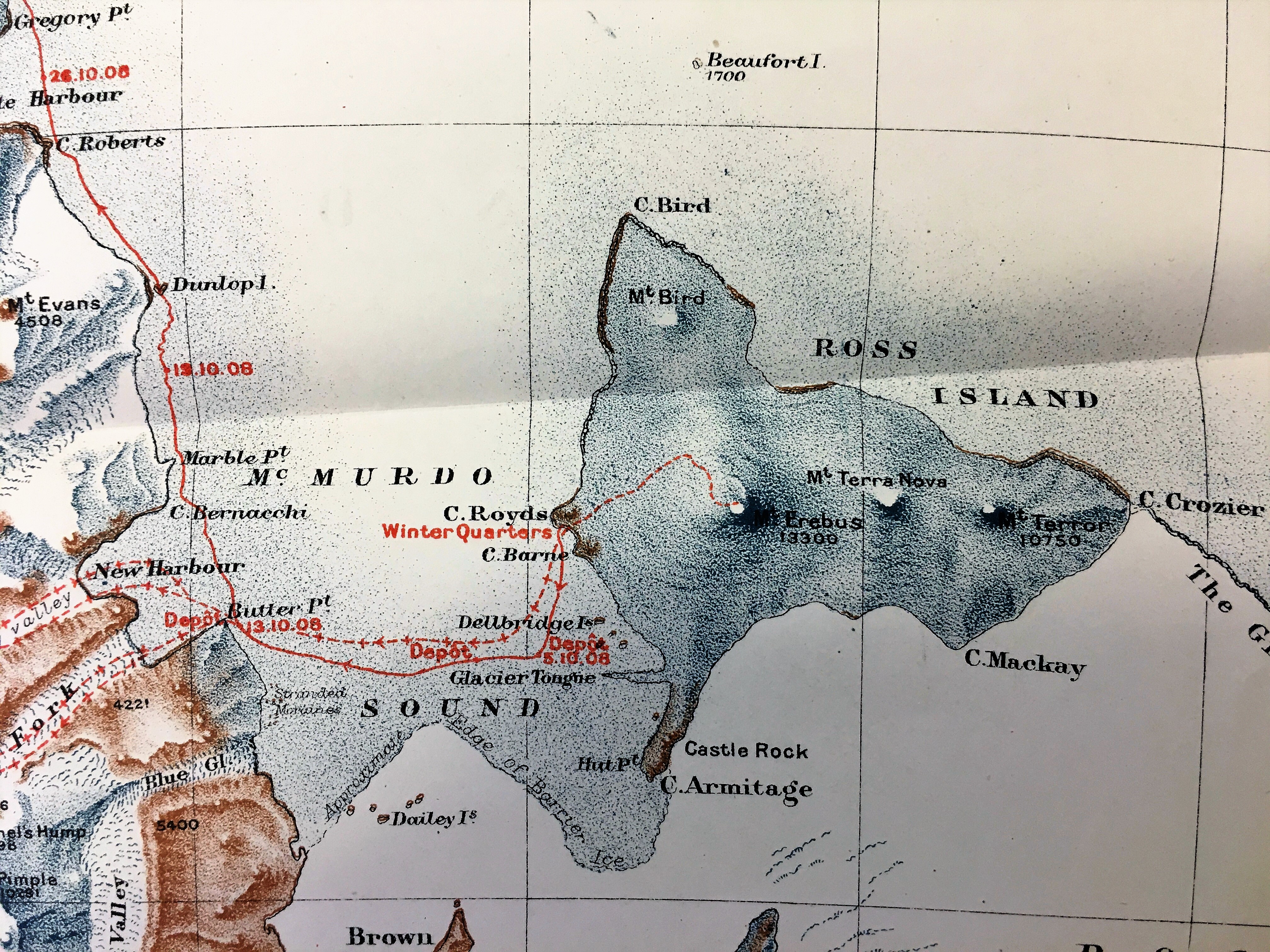

An Australian member of Nimrod Expedition, Douglas Mawson, created the maps of the expedition from surveys he and other members undertook. A geologist at the University of Adelaide by profession, he was ideally placed to do this work.

The maps show the Expedition’s Winter Quarters at McMurdo Sound, Cape Royds, and their routes on land and ice. The style of the maps is attractively spare but almost illustrative. Printed in colour, the depiction of relief is mainly pictorially stippled with the names of the features are a mixture between prosaic (Brown Island, Snow Valley) and commemorational such as Mount Evans, Mount Doorly, both named by Captain Scott during the earlier Discovery Expedition after colleagues. Also notice the Royal Society Range – it’s always good to keep your sponsors onside. The routes show the first ever ascent of Mount Erebus, the second highest volcano in Antarctica, and the route southwards. It is poignant that the route stops not at the South Pole but at the map edge, dated “16.1.09 Lat. 72° 25’ Long. 155° 16’.”. However, this was the furthest south anyone had reached at that time.

the maps is attractively spare but almost illustrative. Printed in colour, the depiction of relief is mainly pictorially stippled with the names of the features are a mixture between prosaic (Brown Island, Snow Valley) and commemorational such as Mount Evans, Mount Doorly, both named by Captain Scott during the earlier Discovery Expedition after colleagues. Also notice the Royal Society Range – it’s always good to keep your sponsors onside. The routes show the first ever ascent of Mount Erebus, the second highest volcano in Antarctica, and the route southwards. It is poignant that the route stops not at the South Pole but at the map edge, dated “16.1.09 Lat. 72° 25’ Long. 155° 16’.”. However, this was the furthest south anyone had reached at that time.

The maps were drawn once the party returned to England and were issued in The heart of the Antarctica by Ernest Shackleton which was published in 1909 as a weighty two volume work.

The heart of the Antarctic 2036 d.17,18

Aurora Australis Broxb. 51.14