From the late nineteenth century many commercially produced maps featured advertisements for products completely unrelated to the map. The advertisements can be fascinating in their own right, and a few examples are shown here.

An earlier blog post features a map of the Manchester Ship Canal from 1889, and it’s worth taking a closer look at a few of the advertisements on and around it. This one, for Sanitary Rose Powder, features a graceful woman in a rather classical dress holding the product aloft; it appears to be endorsed by the Queen, but this probably refers to the magazine of that title rather than to Her Majesty.

The target market for this map seems to be fairly comprehensive; it promotes a great variety of items besides soap powder: security locks, toothpaste, local hostelries, furniture, marquees and two different kinds of sewing machine. The inclusion of an advertisement for Musgrave’s patent stable fittings, “adopted by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales and supplied to the best stables in the United Kingdom”, with an illustration of a glossy horse pawing the ground, adds a touch of class.

Advertisements on maps are often an interesting source of social history. A road map of Great Britain produced by the popular weekly magazine “Tit-Bits” around 1920 has a particularly egregious example of advertising on the back panel: it features a health drink called Wincarnis (which is evidently wine with a few additions). It is presented as a solution to “Why married women lose their looks” (the implication is that this will encourage husbands to stray). A few glasses of Wincarnis, starting at 11:30 am and continuing through the day, will help the frazzled wife to regain her equanimity and “within a few days your looks will begin to come back.” There is so much wrong with this to the modern reader that it’s hard to know where to begin, but we can at least say that it would be unlikely to work. Interestingly, the many other advertisements on the map (bike lamps, radio valves, car batteries) appear to be aimed at a masculine market.

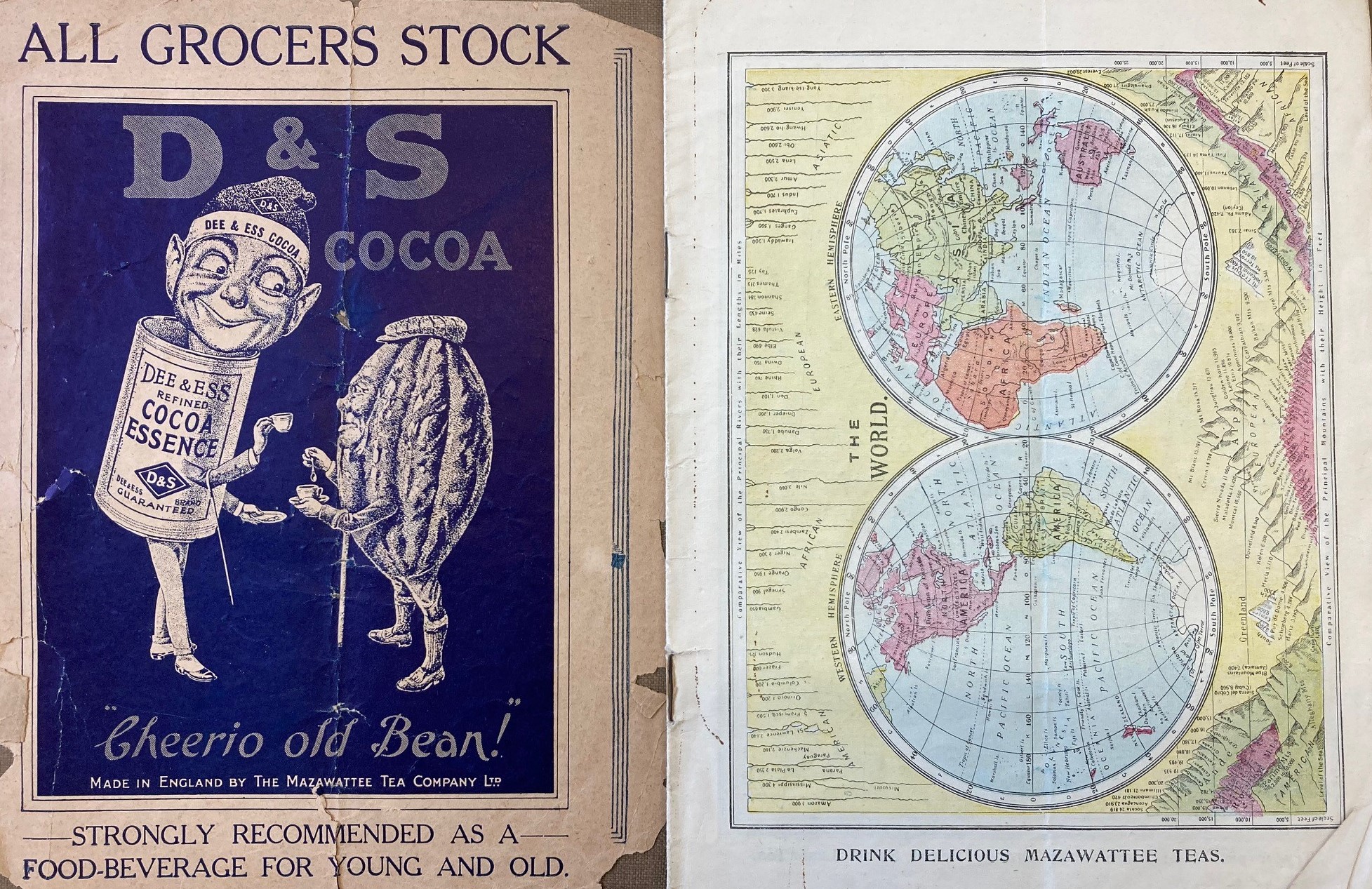

There are also examples of maps and atlases produced specifically to promote a product. The Mazawattee Tea Company (established in 1887 and still in business) produced a small paperback atlas of the world around 1900. The maps are general and make no attempt to highlight tea growing areas, but every page has a slogan urging the reader to drink Mazawattee teas (apart from one which urges them to try a brand of cocoa made by the same company). They also published a dictionary, a gazetteer and a guide to the language of flowers, amongst other things.

Sunlight Soap, another company founded in the 1880s and still in business (now a subsidiary) made a innovative promotional map, the Sunlight Quick-Find Map, in the 1930s. An attached ruler and gazetteer could be used to locate “300 important places in the United Kingdom,” including of course Port Sunlight, the model village on the Wirral established by the company for its workers.

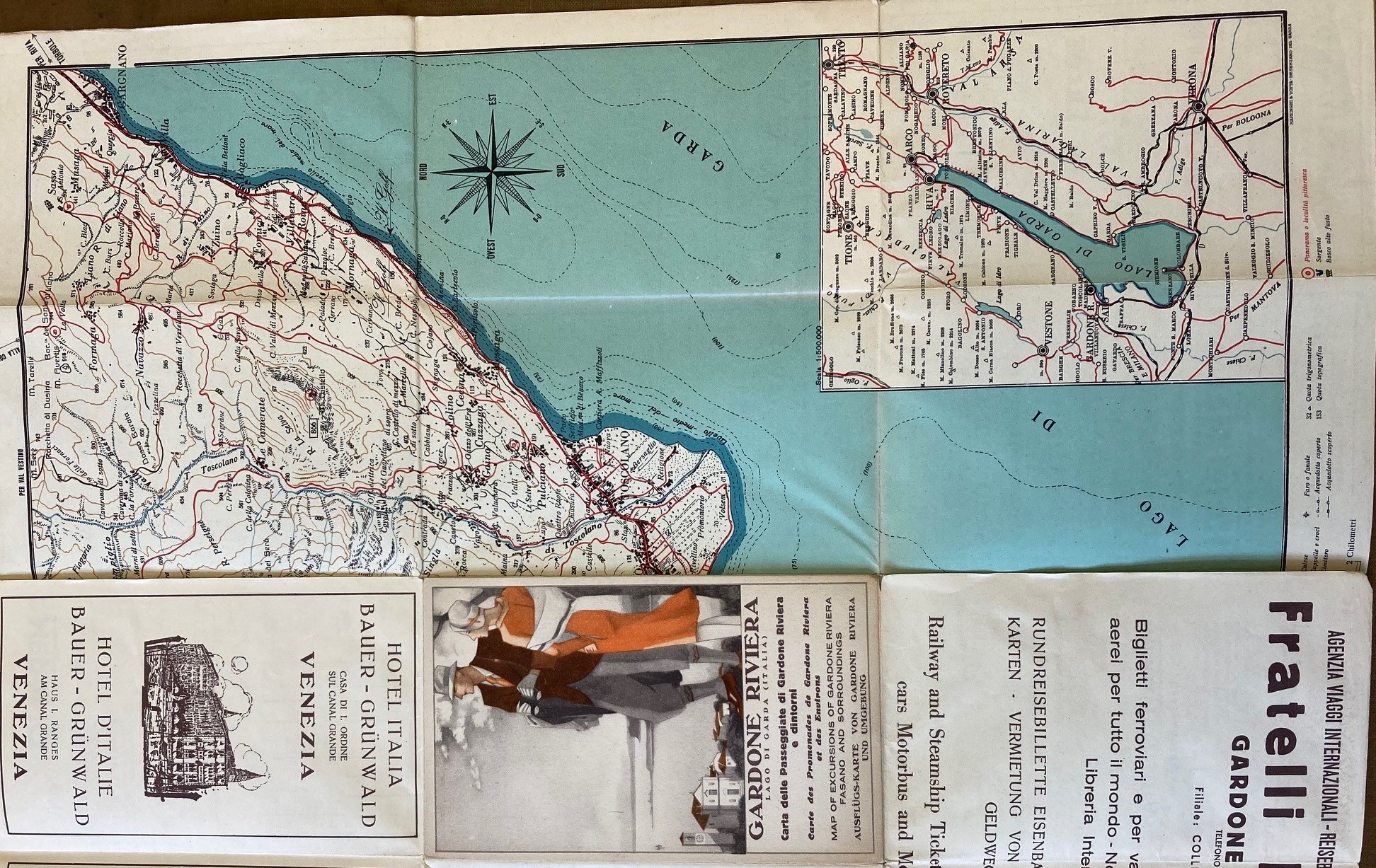

Sometimes the advertisements do have a connection with the map. The Italian map below of excursions around Lake Garda, from the 1930s, features many advertisements for local services. An advertisement for Esso fuel portrays Esso as a mythological character, perhaps a Roman god.

The map itself is detailed and practical, and clearly aimed at international tourists; the cover text is in English, French and German as well as Italian. The cover image makes travel to the area look both stylish and desirable. It could easily provoke a wish to visit Lake Garda, ideally in the 1930s and while wearing a cloche hat.

Manchester ship canal – general plan of canal and district. Revised. [Manchester] : J. Heywood, 1885. C17:3 (13)

“Tit-Bits” road map of England and Scotland. [Edinburgh] : Edinburgh Geographical Institute, [1920s]. C16 (737)

Mazawattee atlas of the World London : Mazawattee Tea Co., Ltd., [ca 1900]. B1 c.484

Sunlight quick-find map. [1935] C15 d.200

Gardone Riviera : Lago di Garda (Italia). Gardone Riviera : Agenzia Viaggi Fratelli Molinari, 1932. C25:17 (59)