This atlas seems to have had a hard life. The printed maps, dating from the early eighteenth century, are nicely engraved and hand coloured but most are stained and tatty and have been heavily folded to fit into the binding. On closer inspection it is not a published atlas as such, but a collection of separately published maps, in French, Latin or English, bound together. Some of the maps are incomplete, others have been repaired, their tattered edges strengthened with thick paper. Some of the most interesting information, though, is on the backs. The large sheets have been used as scrap paper for pen and ink drawings, maps of parts of the Middle East with detailed latitude and longitude shown in the borders. The back of this map of Tartarie by the respected French mapmaker Guillaume de L’Isle has been used for a map of Syria and Lebanon.

The latter part of the book contains smaller plain sheets which have been used for sketch maps and for lists of place names and page references. The text is a mixture of English, Arabic and Latin. This map shows an area to the south of the previous one, covering modern day Israel and Palestine. The Sea of Galilee and Dead Sea are marked and the towns of Haifa and Acre (Acca) can be seen on the coast; a few place names on this map are in Hebrew.

There are also some more detailed maps, such as this one of the rivers of southern Iraq showing Basra and Al-Qurnah.

Who was responsible for this work, and why? There is a clue on one of the later pages in two incomplete drafts of a letter asking for money to continue the project. The first begins by explaining that the writer has been unable to visit because of both poverty and ill health, and explaining: “I have begun to put to the press my Geography of Abulfedah, and near 20 sheetes are work’d off continuing the whole of Arabia and part of Egypte …” before going on to describe his financial needs and his inability to support his family. This is crossed out, and a second draft takes a more optimistic note: “Being pretty well recovered of my late indisposition … when such a fair promise takes effect I’ll go on chearfully in my undertaking, and return my hearty thanks in a dedication …” The reference to the Geography of Abulfedah makes it seem almost certain that this book was the property of Jean Gagnier, who published a translation from Arabic of the “Taqwim al-buldan,” or geographical description, of Abū al-Fidāʾ (or Abulfeda) a fourteenth century Kurdish geographer. Publication was delayed by lack of money; Gagnier’s “Descriptio peninsulæ Arabum” appeared in 1740, shortly before the writer’s death, and was incomplete, covering only Arabia and part of Egypt . The letter asking for financial support would appear to have been unsuccessful if it was ever sent.

The published work does not appear to have contained any maps. It’s interesting to see the parallels between Gagnier’s interpretation of Abū al-Fidāʾs work, and earlier European works based on Ptolemy’s Geography. Ptolemy’s work included only geographical description, without surviving maps, but later interpretations and translations included maps based on the written account. Gagnier seems to have had it in mind to do something similar. Towards the end of the book is a table where Gagnier has compared the latitude and longitude of places (including Baghdad, Jerusalem and Alexandria) as calculated by Ptolemy, Abū al-Fidāʾ and the contemporary mapmaker de L’Isle, perhaps attempting to reconcile them. At least some of the maps were used as source material as well as scrap paper.

Gagnier was brought up in France but lived in Oxford from the early 1700s, teaching Hebrew and Arabic; he also published translations, including a life of Mohammed in Latin based on Abū al-Fidāʾs Arabic text, and a chronicle based on the work of the Hebrew historian Josephus. The Bodleian also holds some of Gagnier’s manuscript notes and preparatory material for his published works. This volume of maps was acquired by the library in 1885, along with a misleading contemporary note attributing the manuscript maps to someone else entirely. Further research in 1913 identified the connection with Gagnier, but it does not appear to have been widely publicised.

[A collection of manuscript maps and notes, apparently created in the preparation of Gagnier’s Descriptio peninsulæ Arabum.] Oxford, [between 1727 and 1740]. Map Res. 73

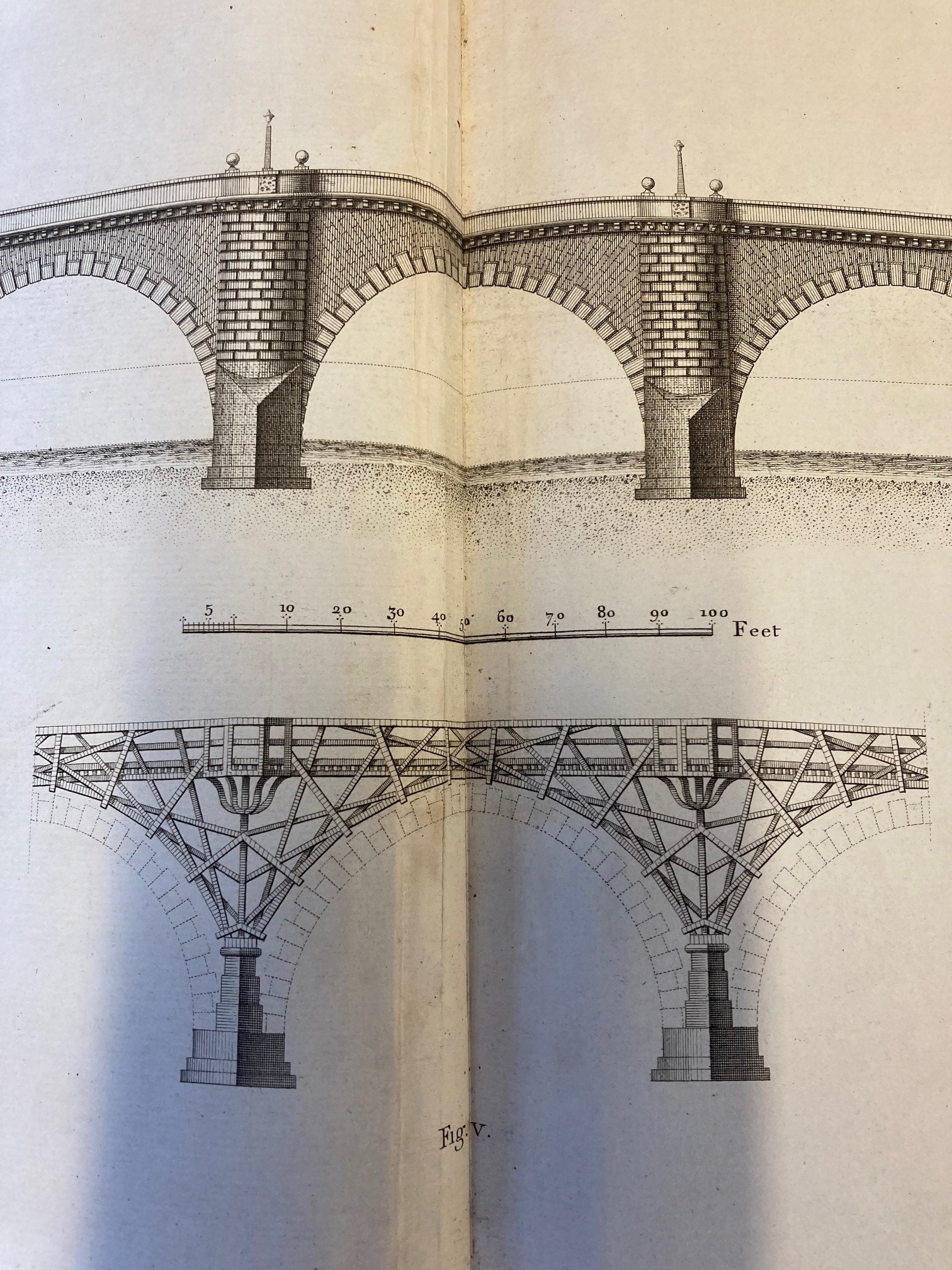

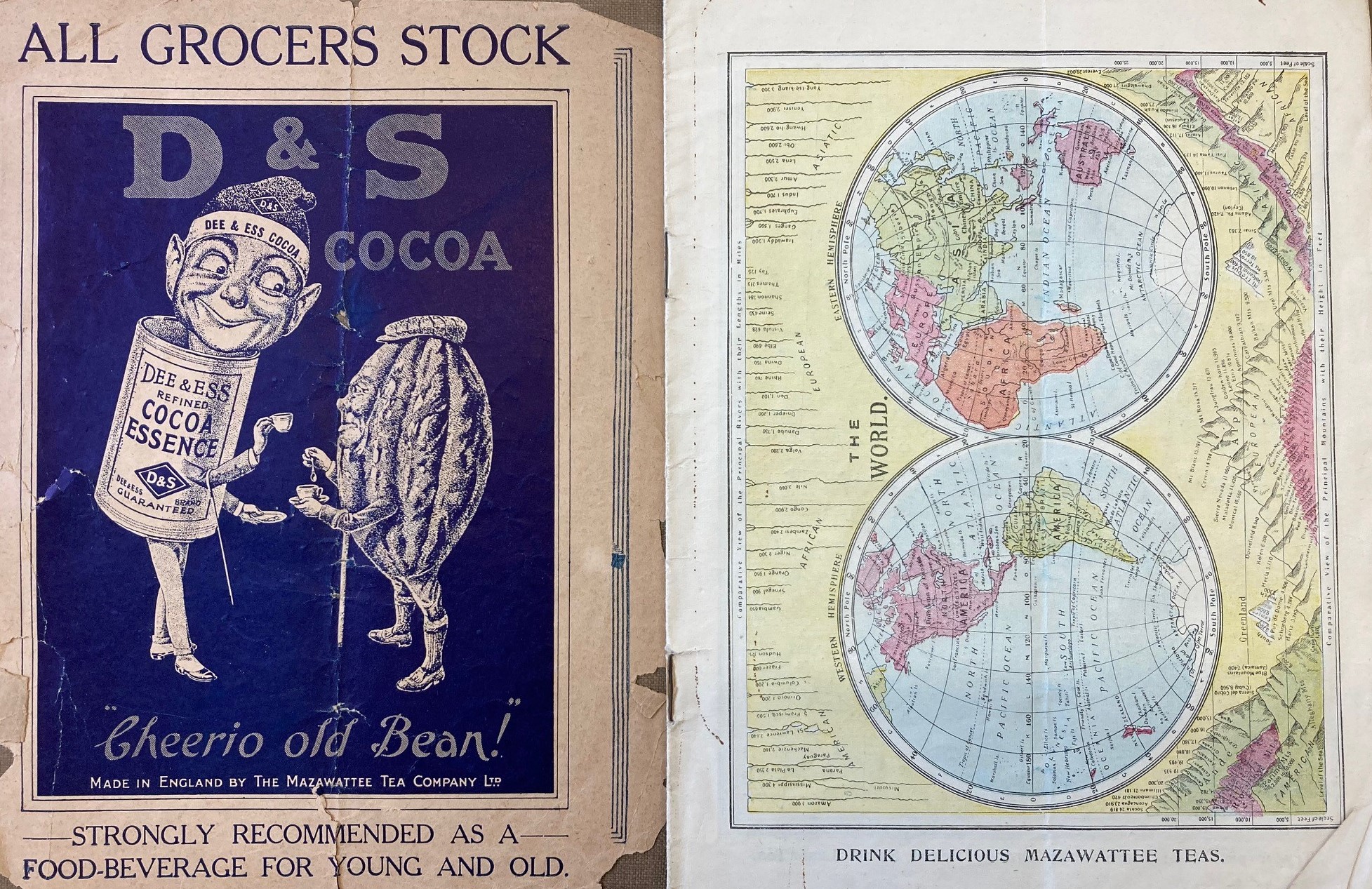

The plan above was made in the late 1880s, probably once the canal was under construction. The section here shows the relative shallows of the Mersey estuary bypassed by the canal. It is surrounded by advertisements for huge a variety of products, including toothpaste and medicines, and domestic items such as sewing machines and locks; a detailed inset plan of the Manchester and Salford Docks promotes both furniture and ale.

The plan above was made in the late 1880s, probably once the canal was under construction. The section here shows the relative shallows of the Mersey estuary bypassed by the canal. It is surrounded by advertisements for huge a variety of products, including toothpaste and medicines, and domestic items such as sewing machines and locks; a detailed inset plan of the Manchester and Salford Docks promotes both furniture and ale.