The Map Room was recently given what appeared to be two facsimiles of early printed maps of Paris from the sixteenth century. The smaller one bears a Latin title, “Lutetia vulgo Paris Anno 1575” – a fairly conventional way of giving both the Latin and vernacular versions of a place name in a map title. It’s a colourful, attractive map, showing Paris inside the city walls with the buildings represented pictorially. In the foreground are views, a rural landscape and a view of the Tour de Nesle, part of the city walls. The map is signed by Josse de Reveau.

So far, this appears a fairly conventional facsimile – a modern printed copy of an attractive early map. But on closer inspection it becomes puzzling. There is no other trace of Josse de Reveau or of the original on which the map was based. The explanation is that the map is actually a reconstruction, originally made in the 1950s by a French artist; inspired by an engraving from the time of Henri III, who was King of France from 1574 to 1589, Daniel Derveaux copied the style and drew Paris as it was in the sixteenth century. According to the company website (the map is still for sale, along with a number of similar maps and map themed gifts), “He signed ‘Josse de Reveau’ to make it look authentic.” The name could be an adaptation of Derveaux’s real surname. The map has fooled many into thinking that it is a facsimile of a sixteenth century map, and it is recorded thus in several library catalogues. We have not identified a specific map from which the information was taken.

A second map of Paris in the same category was acquired at the same time. This has an even more complex history in terms of the origins of the information. The title in a scroll design across the top of the maps is “Icy est le vray pourtraict naturel de la ville, cité, université de Parisy;” both the wording and the archaic spelling are copied directly from a large and detailed map of Paris made in the mid-sixteenth century by Olivier Truschet and Germain Hoyau. Some of the decorative elements on this map are taken from the same source. The original is held in the university library in Basel, Switzerland.

The map itself is smaller and simpler than that produced by Truschet and Hoyau, and is largely based on the one published by Braun and Hogenberg in their Civitates orbis terrarum, an atlas of the world’s cities in six volumes which appeared from 1572. The foreground is occupied by human figures; two labourers, two ladies in grand dresses, and two finely dressed gentlemen, one on a horse. There is also a view of Paris along the bottom. We have been unable to identify the source of these images, so at least three, possibly four sources went to make up this composite map. Again there is a fictional cartographer, and this time a publisher as well; “Rossingol execut [made] 1576. A Paris, chez Melchior, Quai du Port au Foin qui regarde l’Ile Nostre Dame” – the publisher and address look authentic and convincing, but are invented. There is no definite evidence as to the origins of this reconstruction; it may well be the work of Derveaux again, but it dates from the 1930s and the company has no record of it.

It is difficult to know what to make of these maps – were they originally made as a deliberate attempt to deceive, a whimsical experiment, or a way of improving access to historical sources? As regards the historical information on the maps, they are fairly useful; the details seem to have been quite closely copied from early maps. Having said which, we should also remember that no map can be relied on entirely to show the landscape as it was at a given time – but that probably deserves a separate discussion.

Lutetia vulgo Paris Anno 1575. Daniel Derveaux, 1958. C21:50 Paris (208)

Icy est le vray pourtraict naturel de la ville, cité, université de Parisy. Publisher not identiifed, [1930?] C21:50 Paris (209)

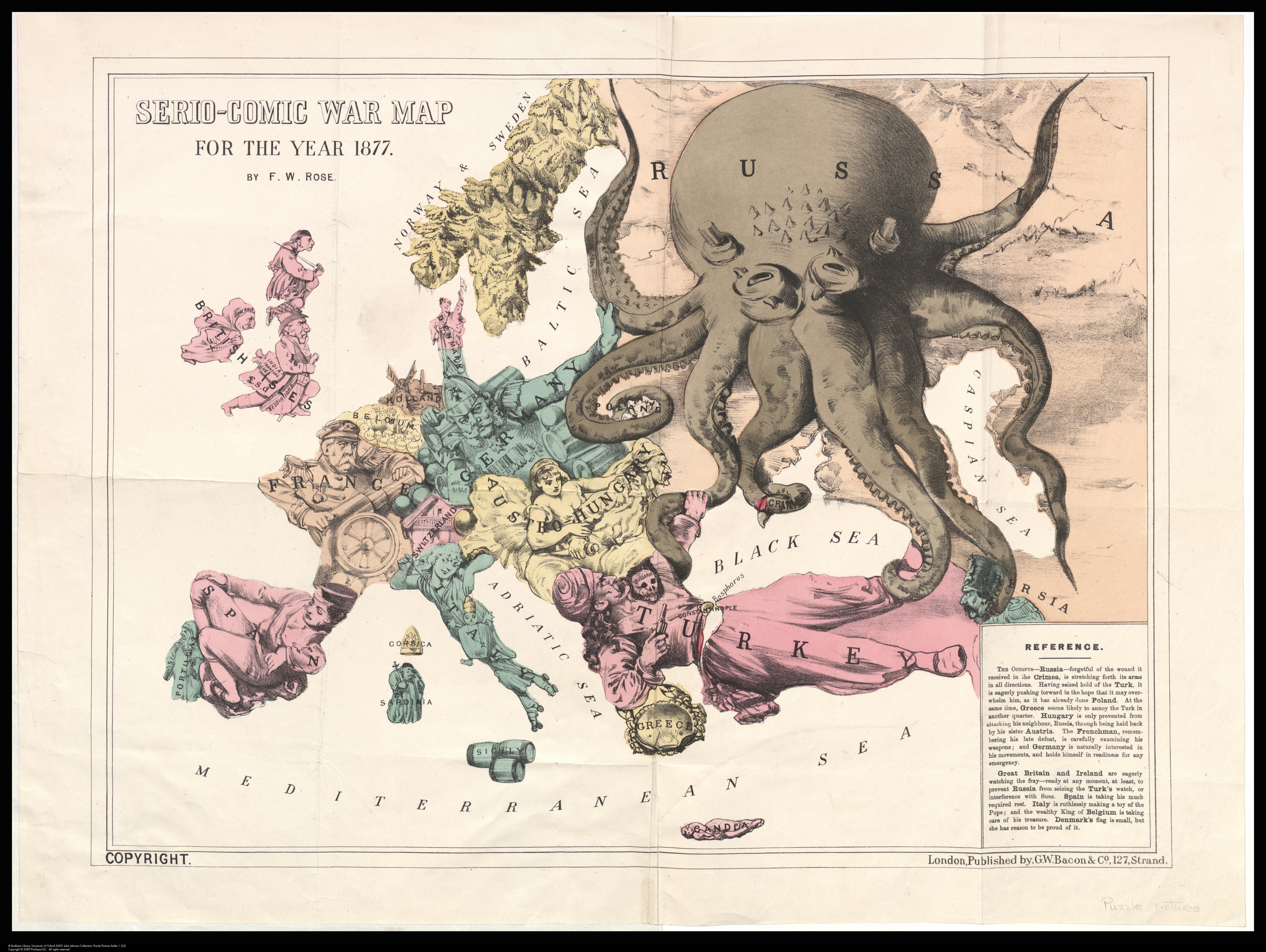

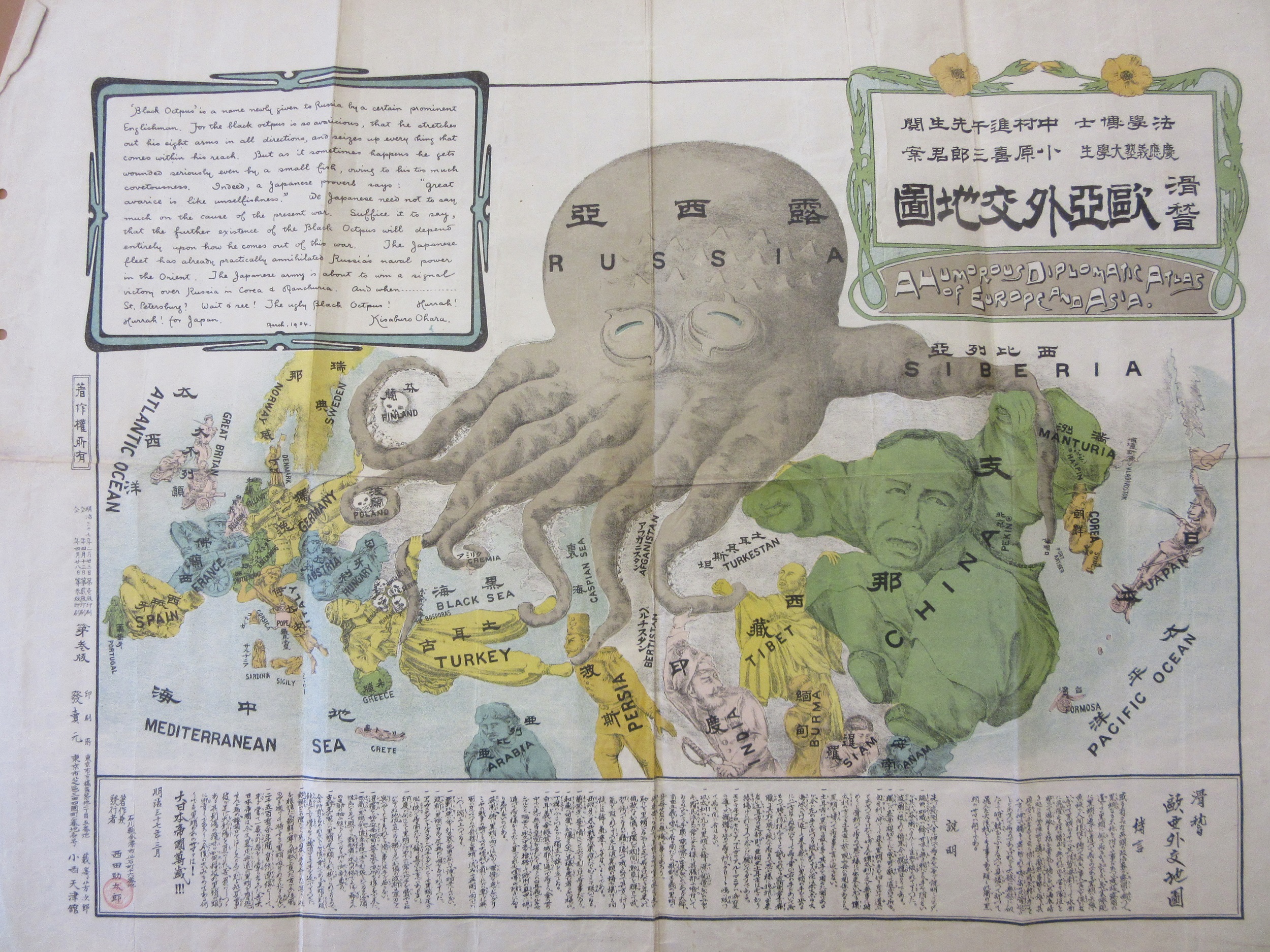

The 1904 map is a strange mix of quality and some parts definitely work better than others. The new parts, which is pretty much everything east of Persia, have a fresh look and have enough space for the countries to be represented well while with the reduced size of the map from the original Europe is a bit too crowded. Scandinavia in particular looks bad compared to the 1877 version. Italy is intriguing, treating the Pope and the Vatican like a toy on string following the defeat of Rome and the Papal States in the war to unify Italy in 1870.

The 1904 map is a strange mix of quality and some parts definitely work better than others. The new parts, which is pretty much everything east of Persia, have a fresh look and have enough space for the countries to be represented well while with the reduced size of the map from the original Europe is a bit too crowded. Scandinavia in particular looks bad compared to the 1877 version. Italy is intriguing, treating the Pope and the Vatican like a toy on string following the defeat of Rome and the Papal States in the war to unify Italy in 1870.

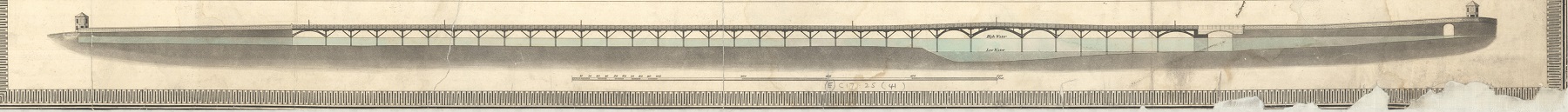

The point of origin is probably Ben Cleuch in the Ochil Hills. There is a note stating that it covers “about 85 degrees of the horizon” – nearly a quarter of a circle, stretched out to a view almost two metres long. The view was engraved by Daniel Havell in London, and printed in colour, a quite early example of a colour lithograph.

The point of origin is probably Ben Cleuch in the Ochil Hills. There is a note stating that it covers “about 85 degrees of the horizon” – nearly a quarter of a circle, stretched out to a view almost two metres long. The view was engraved by Daniel Havell in London, and printed in colour, a quite early example of a colour lithograph.