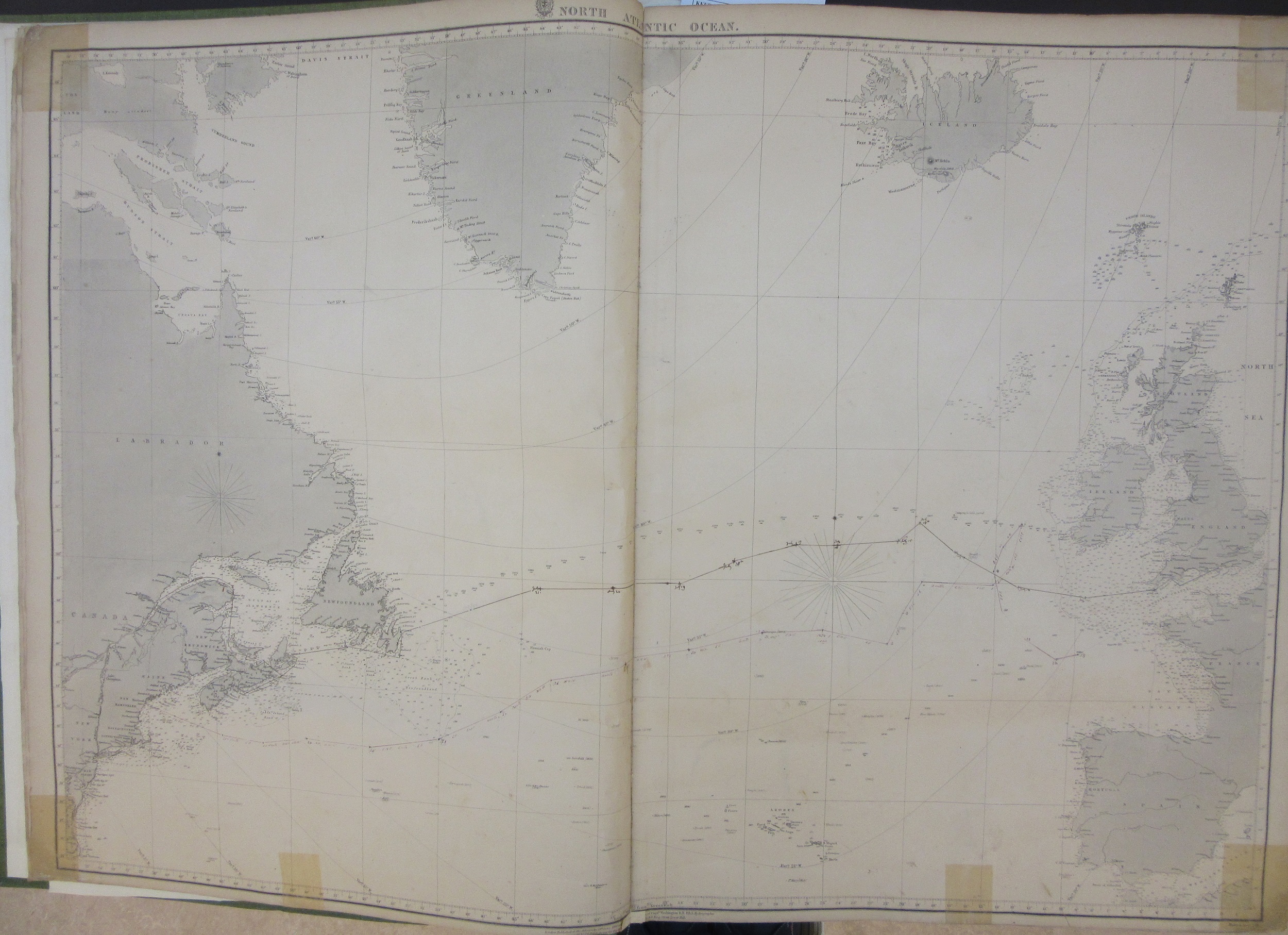

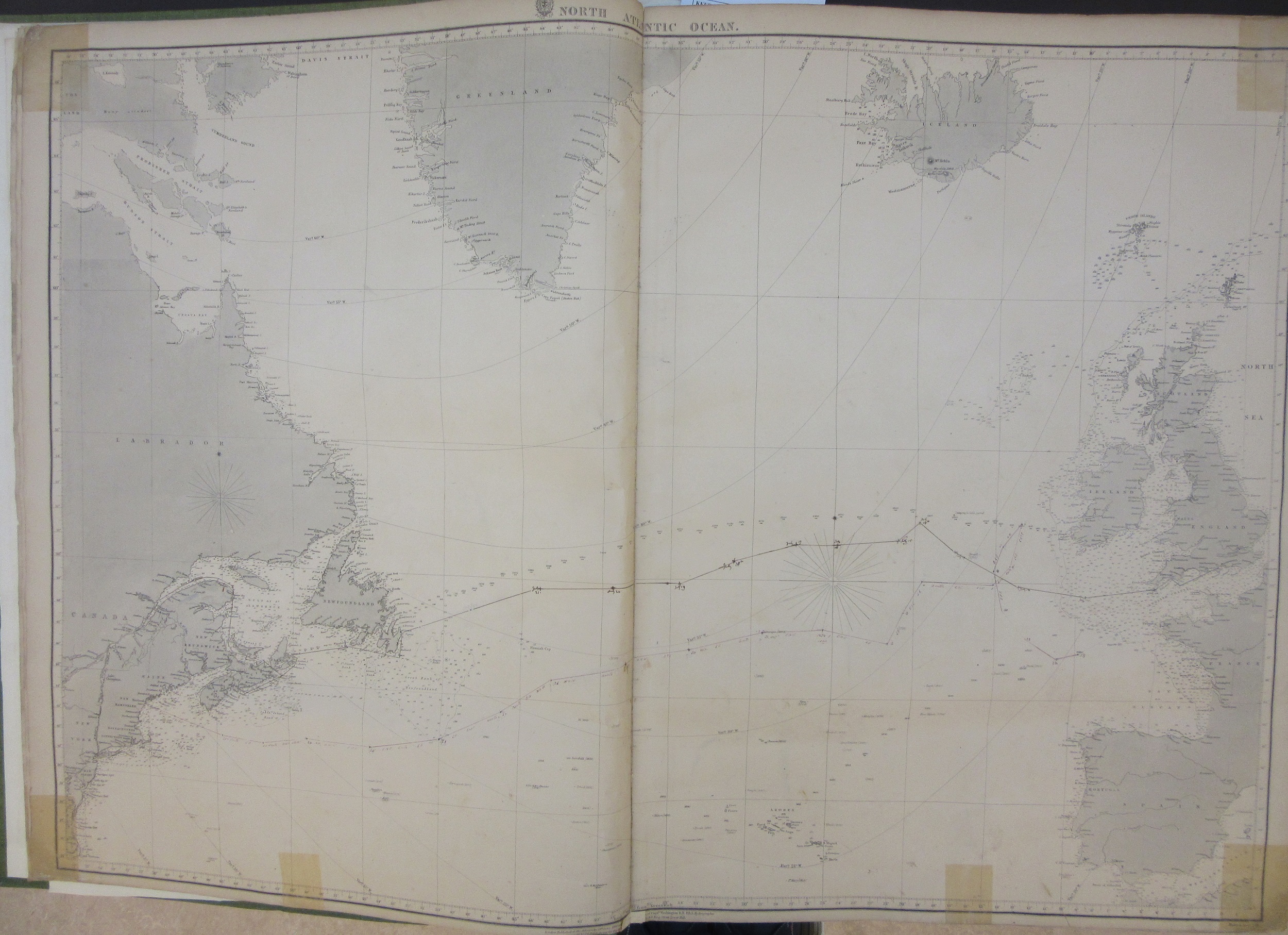

Admiralty Charts have a reassuring familiarity about them. The Hydrographic Office of the Admiralty first started publishing maps in 1800 and this map from 1860 uses cartographic conventions still in place today. This sense of timelessness comes from the charts concentrating on hydrographic information; soundings, rocks, beacons and so on, features that don’t alter over time. Almost all our cartographic charts in the Bodleian come from legal deposit in pristine condition. I say almost because we do have a number of donated charts as well. What is special about this particular donated map is that it is a chart that has been used, a course has been plotted of a voyage made between July and August of an unspecified year by an unknown ship. A chart used as intended.

North Atlantic Ocean, published at the Admiralty, 18th June, 1860. B1 a.19

The challenge is to try and discover more about the journey, which really comes down to when and what ship? All we have to go on when looking at the chart is the route, from Southampton across the Atlantic to Quebec, with positions at noon each day from July 10th to August 18th. A seemingly impossible task but there is a clue separate from the map. The chart is one of a number bound up in a volume with the simple title Charts of the Gulf & River St. Lawrence by Capt. H.W. Bayfield, R.N and on the contents page there is a hastily written note in pencil that is the key to the mystery . Sir Henry Acland has a strong connection with Oxford and the Bodleian. Born in Exeter in 1815 Acland became a Fellow of All Souls College and then in 1851 Physician to the Radcliffe Infirmary and Radcliffe Librarian in the Radcliffe Camera which had been, since built, the home of the Radcliffe Science Library. It was during Acland’s time as Librarian that the collection of books moved to a new Radcliffe Science Library and the Camera became part of the Bodleian. This explains Acland’s close relationship with the Bodleian, and the reason why he donated the set of nautical charts to the library in July 1880.

across the Atlantic to Quebec, with positions at noon each day from July 10th to August 18th. A seemingly impossible task but there is a clue separate from the map. The chart is one of a number bound up in a volume with the simple title Charts of the Gulf & River St. Lawrence by Capt. H.W. Bayfield, R.N and on the contents page there is a hastily written note in pencil that is the key to the mystery . Sir Henry Acland has a strong connection with Oxford and the Bodleian. Born in Exeter in 1815 Acland became a Fellow of All Souls College and then in 1851 Physician to the Radcliffe Infirmary and Radcliffe Librarian in the Radcliffe Camera which had been, since built, the home of the Radcliffe Science Library. It was during Acland’s time as Librarian that the collection of books moved to a new Radcliffe Science Library and the Camera became part of the Bodleian. This explains Acland’s close relationship with the Bodleian, and the reason why he donated the set of nautical charts to the library in July 1880.

An extract from the chart showing the route taken to Quebec, sailing through the wonderfully named Gut of Canso (also called the Gut of Canseau) between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

An extract from the chart showing the route taken to Quebec, sailing through the wonderfully named Gut of Canso (also called the Gut of Canseau) between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

Research into Acland’s life then explains the rest. In 1860 he became physician to H.R.H. the Prince of Wales (who later became Edward VII) just before he went on an official trip to Canada and the United States onboard H.M.S. Hero, the first time a Prince of Wales had made this journey. The map charts the daily position of the Hero as it voyaged across the Atlantic.

The Gut of Canso (here called Canseau) taken from one of the other charts in the volume. The numbers are soundings while the yellow colours show the positions of lights, which could either be fixed (indicated by the letter F) or revolving (the letter R).

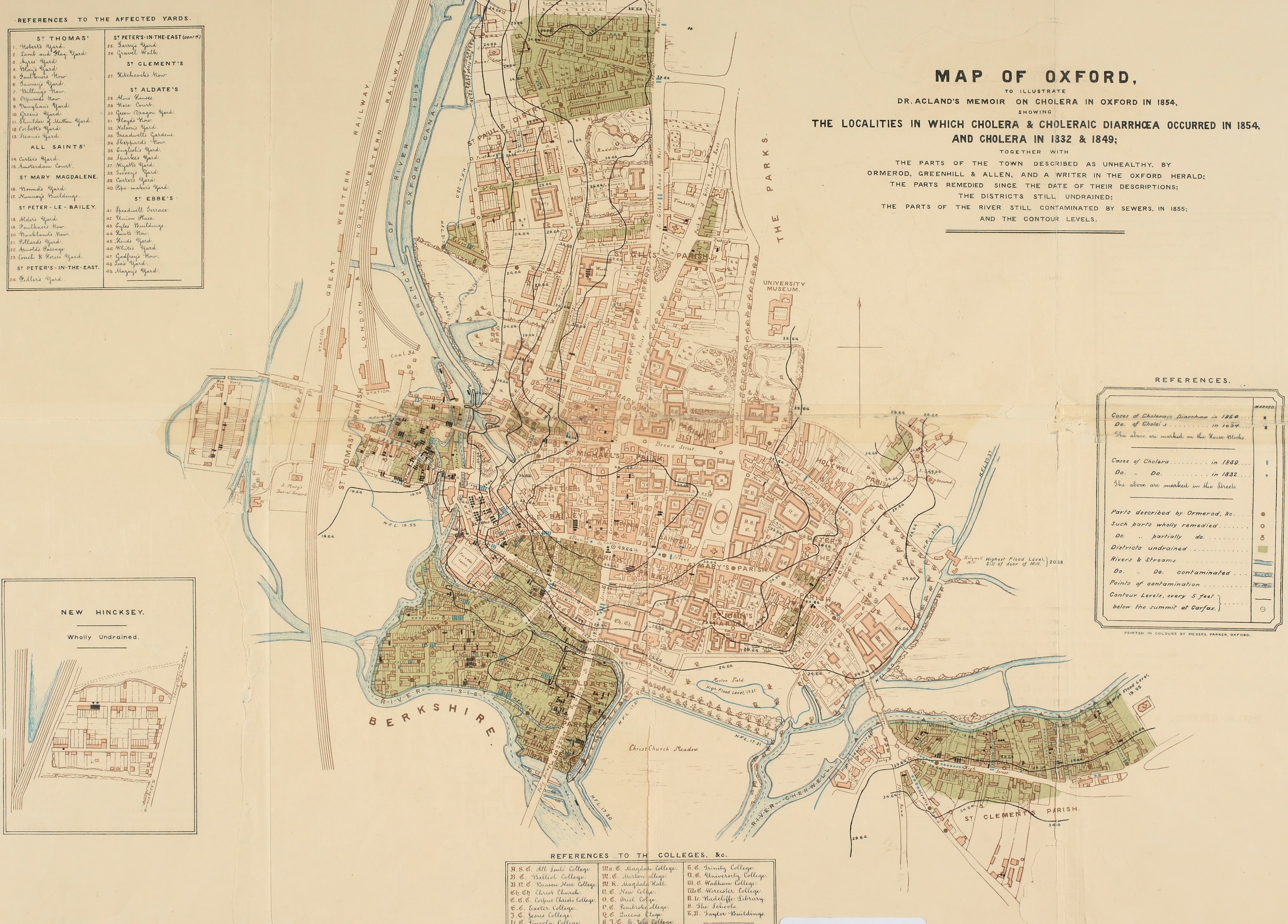

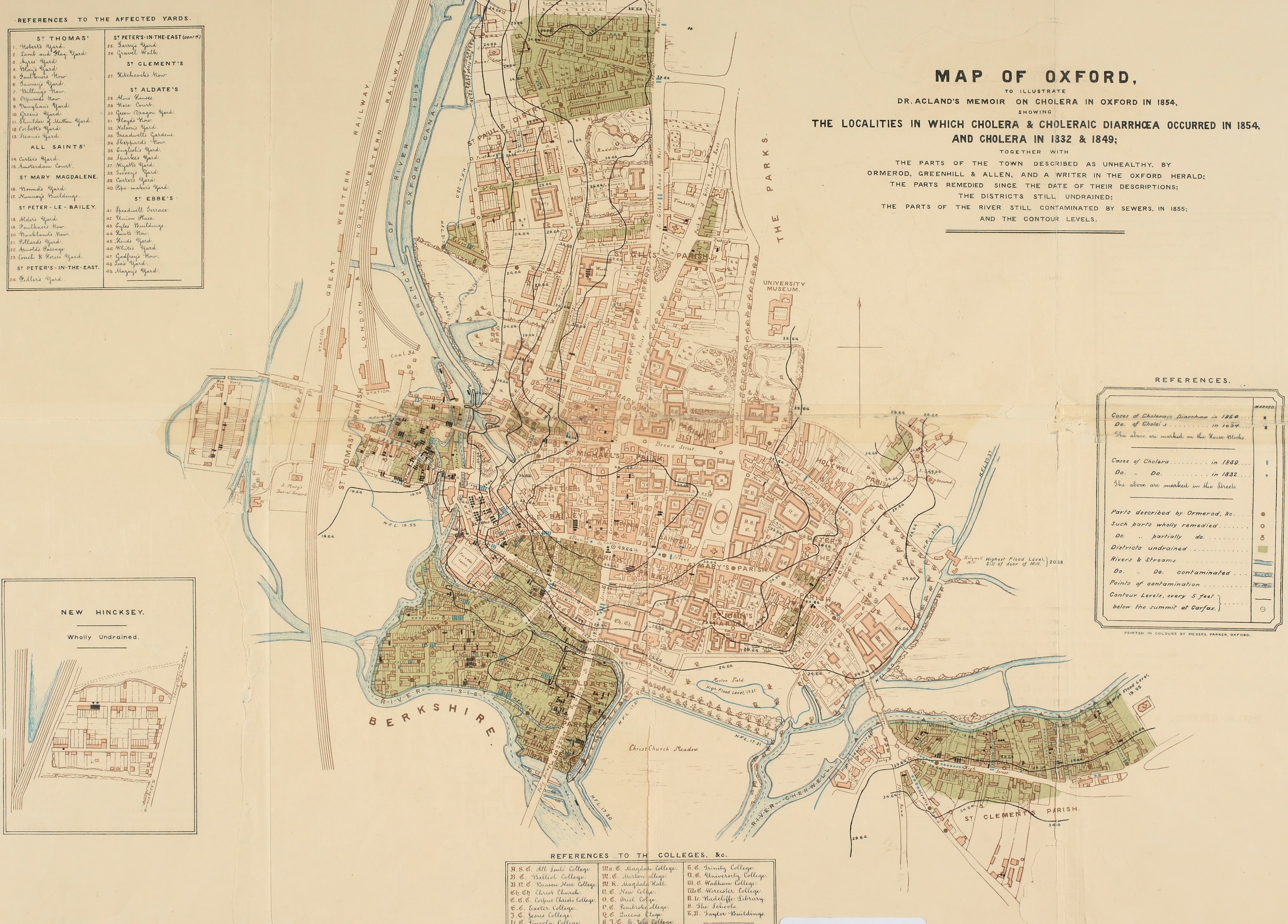

In Oxford Acland is famous for a map made six years before the voyage of the Hero. In 1854 he produced a report on a series of Cholera outbreaks in Oxford which had led to a number of fatalities. It came with a map which highlights the poor sanitary conditions in parts of the city (the areas shaded in green) , the parts of the Thames contaminated and unsafe to drink and the locations where there were cases of Cholera (more on the map can be found here).

Map of Oxford to illustrate Dr. Acland’s memoir of cholera in Oxford in 1854… 1854. C17:70 Oxford (15)

The Acland Hospital, so long a feature on the Banbury Road in Oxford and now at the Manor Hospital in Headington was built as a memorial to Acland’s wife Sarah. A daughter, also called Sarah, was an early photographer, some of her work can be found in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford.

In the year after the voyage a book was privately published by Gardner D. Engleheart. ‘Journal of the progress of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales through British North America and his visit to the United States… (203 a.333)’. The book includes illustrations and text about the visit and, helpfully for the purpose of this blog and identifying the map, a log of the journey out giving positions at noon on each day as well as a number of different diary entries from the voyage. So for instance we learn that the Royal Yacht (the Hero) ‘with the Prince Consort sailed at 4 a.m.’, presumably to catch the tide. Then, far more dramatically, from a different diary on the 12th ‘Man overboard! The gun-room steward jumped out of one of the ports, in a fit of temporary insanity, and was drowned! Every effort was made to rescue him, but he would not be saved.’

In the year after the voyage a book was privately published by Gardner D. Engleheart. ‘Journal of the progress of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales through British North America and his visit to the United States… (203 a.333)’. The book includes illustrations and text about the visit and, helpfully for the purpose of this blog and identifying the map, a log of the journey out giving positions at noon on each day as well as a number of different diary entries from the voyage. So for instance we learn that the Royal Yacht (the Hero) ‘with the Prince Consort sailed at 4 a.m.’, presumably to catch the tide. Then, far more dramatically, from a different diary on the 12th ‘Man overboard! The gun-room steward jumped out of one of the ports, in a fit of temporary insanity, and was drowned! Every effort was made to rescue him, but he would not be saved.’

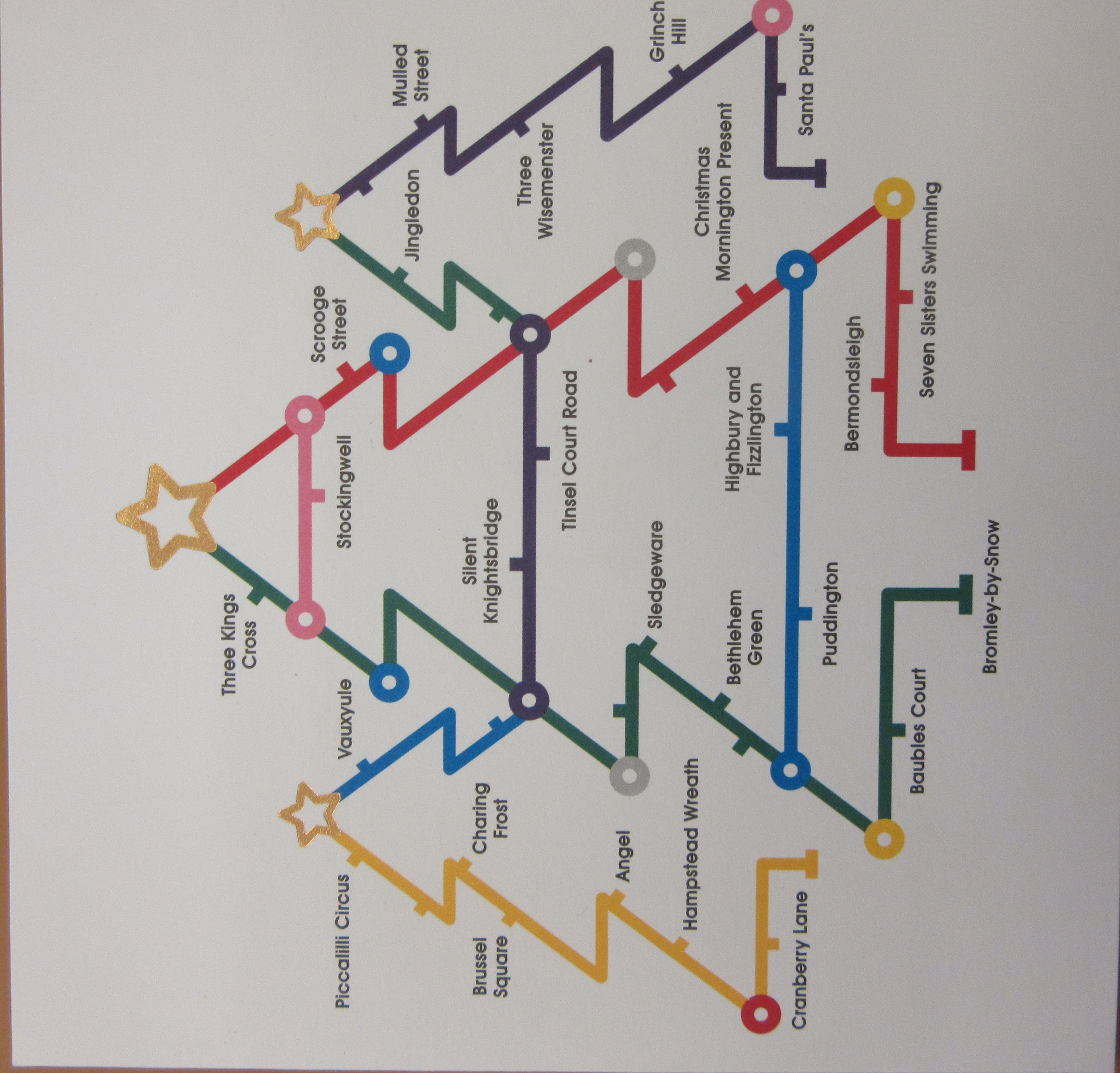

Few people can have more need of a map than Father Christmas. Who else travels the World, at night, visiting every house in every city, town and village? Who else does this but once a year, a long enough gap to forget which turn to take, which lane to go down? Who else makes these journeys on a sleigh drawn by 8 reindeer with no sat-nav, no googlemaps on a smart phone?

Few people can have more need of a map than Father Christmas. Who else travels the World, at night, visiting every house in every city, town and village? Who else does this but once a year, a long enough gap to forget which turn to take, which lane to go down? Who else makes these journeys on a sleigh drawn by 8 reindeer with no sat-nav, no googlemaps on a smart phone?

An extract from the chart showing the route taken to Quebec, sailing through the wonderfully named Gut of Canso (also called the Gut of Canseau) between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

An extract from the chart showing the route taken to Quebec, sailing through the wonderfully named Gut of Canso (also called the Gut of Canseau) between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

In the year after the voyage a book was privately published by Gardner D. Engleheart. ‘Journal of the progress of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales through British North America and his visit to the United States… (203 a.333)’. The book includes illustrations and text about the visit and, helpfully for the purpose of this blog and identifying the map, a log of the journey out giving positions at noon on each day as well as a number of different diary entries from the voyage. So for instance we learn that the Royal Yacht (the Hero) ‘with the Prince Consort sailed at 4 a.m.’, presumably to catch the tide. Then, far more dramatically, from a different diary on the 12th ‘Man overboard! The gun-room steward jumped out of one of the ports, in a fit of temporary insanity, and was drowned! Every effort was made to rescue him, but he would not be saved.’

In the year after the voyage a book was privately published by Gardner D. Engleheart. ‘Journal of the progress of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales through British North America and his visit to the United States… (203 a.333)’. The book includes illustrations and text about the visit and, helpfully for the purpose of this blog and identifying the map, a log of the journey out giving positions at noon on each day as well as a number of different diary entries from the voyage. So for instance we learn that the Royal Yacht (the Hero) ‘with the Prince Consort sailed at 4 a.m.’, presumably to catch the tide. Then, far more dramatically, from a different diary on the 12th ‘Man overboard! The gun-room steward jumped out of one of the ports, in a fit of temporary insanity, and was drowned! Every effort was made to rescue him, but he would not be saved.’