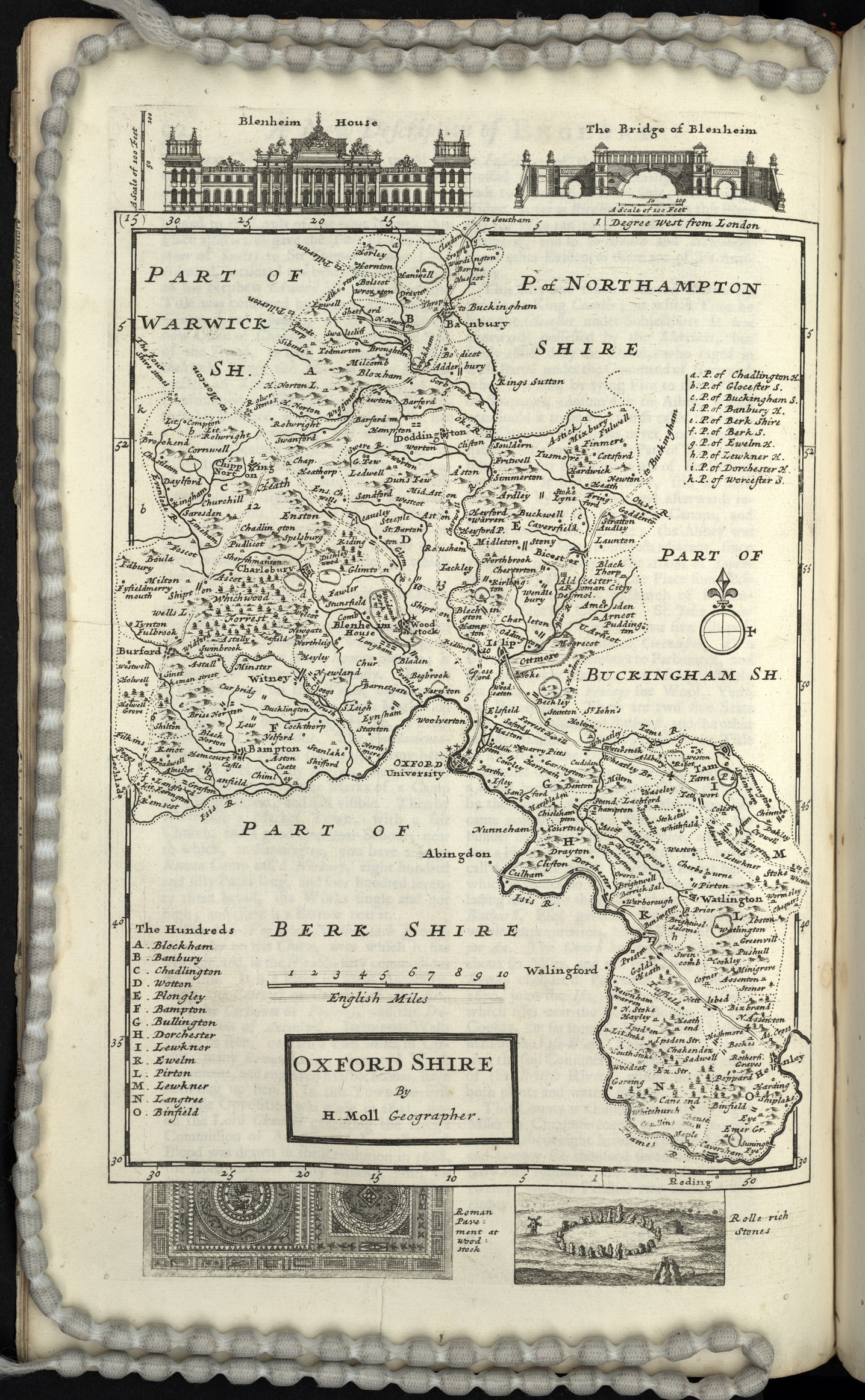

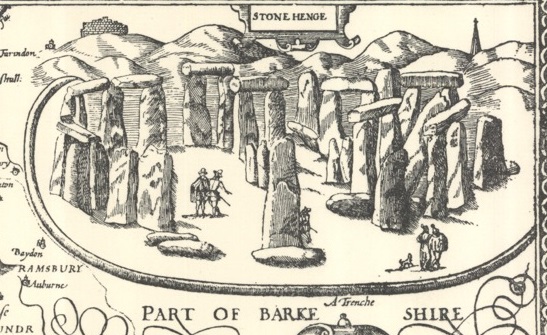

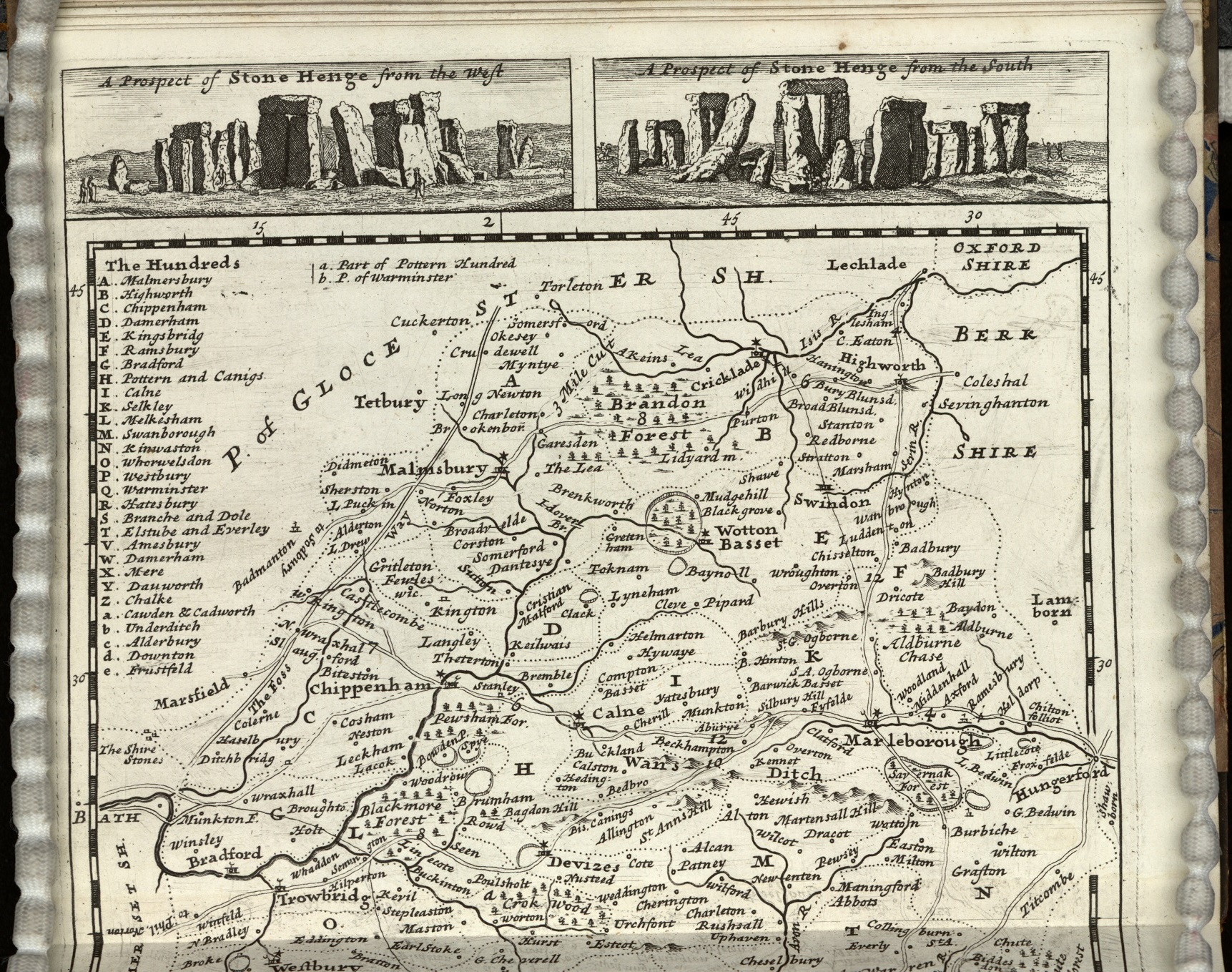

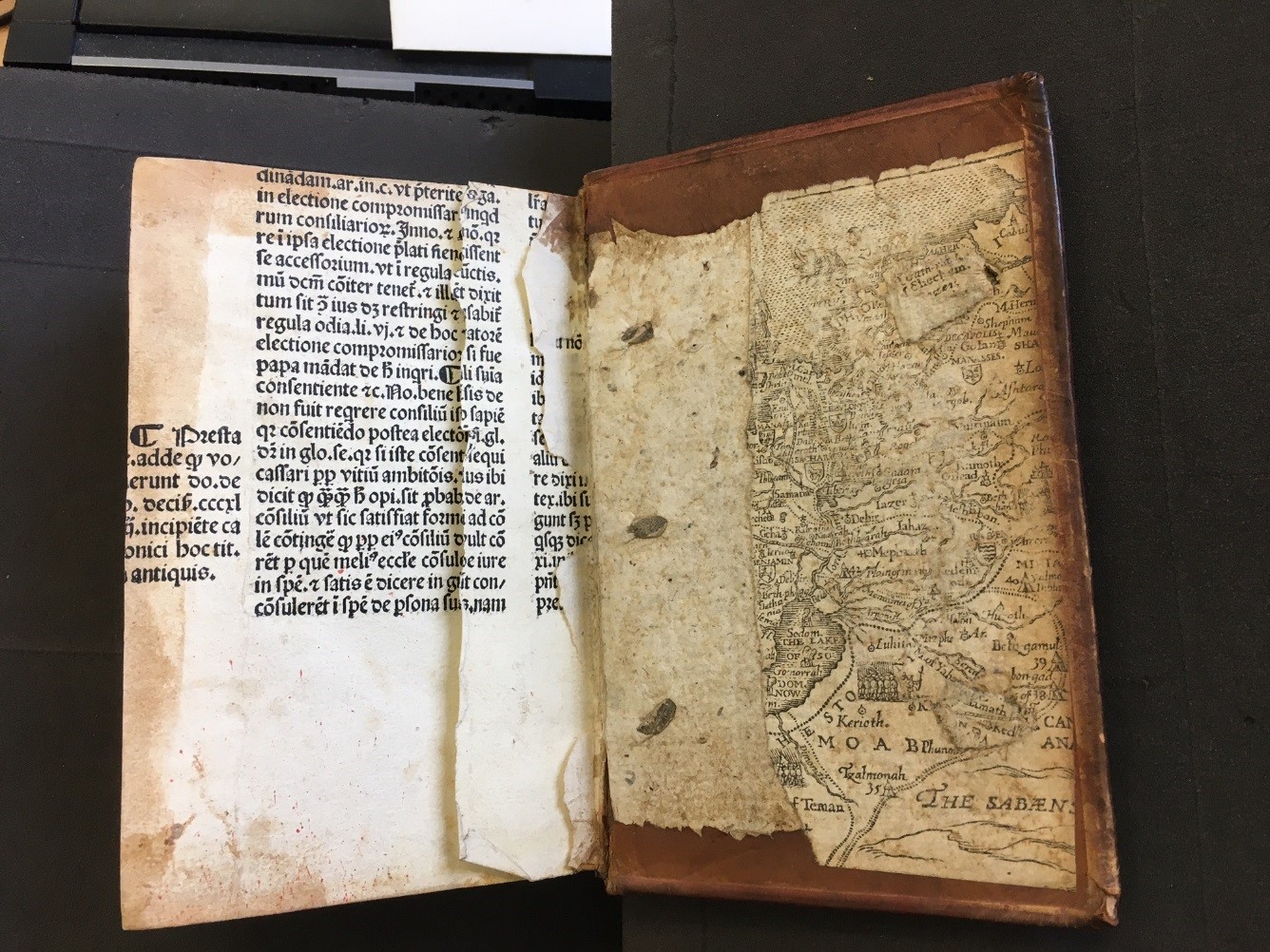

Chalk figures on hillsides are not uncommon especially in southern Britain but they still retain the air of mystery. What are some of them? Who created them? Why are they there? They also caused an issue on maps. Early modern cartographers drew maps but out of necessity gathered information from other surveyors. This is where errors crept in. Imagine an surveyor of the Berkshire Downs at Uffington saying “well, there’s this white horse on the side of the hill”. The prehistoric ‘horse’ famously does not look like a horse therefore the misunderstandings can be seen as a result, most notably the Sheldon tapestry map of Oxfordshire which has a truly majestic (and enormous) white horse striding over the side of the hill.

Richard Hyckes who designed the tapestry was not to know the reality was rather different.

The error was repeated by John Rocque albeit with a more modest horse.

It wasn’t until the Ordnance Survey surveyed the country was the Uffington White Horse depicted as it truly is.

The Cerne Abbas Giant is actually a giant cut into the chalk of Dorset, rather a famous one. He is younger than the horse but his beginnings are still shrouded in mystery but possibly something to do with former Cerne Abbey nearby. For some reason he was only represented as lettering by Isaac Taylor 1765.

However, the Ordnance Survey somewhat sanitised him when the 25” was published in 1888.

The Long Man of Wilmington in East Sussex was not so problematic, so much so that he didn’t appear at all until the OS came along. The map by Thomas Yeakell and William Gardner (1778-1783) ignores him completely – whether they were unaware of the chalk figure or merely swerved the opportunity of representing it history does not tell us.

Sheldon tapestry map of Oxfordshire [1590?] (R) Gough Maps 261

John Rocque. A topographical map of the county of Berks (1761) Gough Maps Berkshire 6

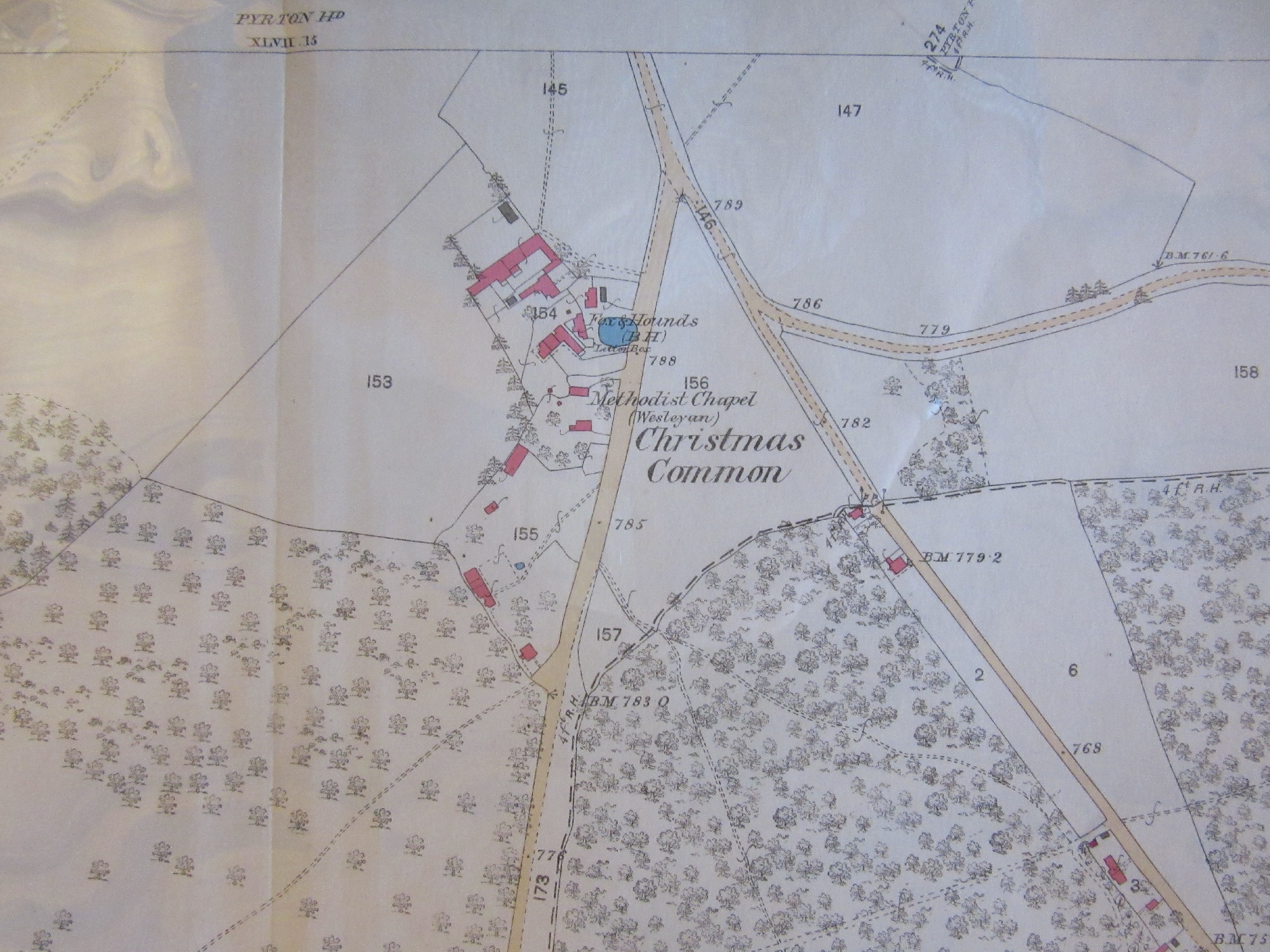

Ordnance Survey 2nd edition 1:2500 Berkshire XIII.14 1899

Isaac Taylor. Dorset-shire. 1765 Gough Maps Dorset 11

Ordnance Survey 1st edition 1:2500 Dorset XXXI.2 1888

Thomas Yeakell, William Gardner. The county of Sussex. 1778-1783. Gough Maps Sussex 14

Ordnance Survey 3rd edition 1:2500 Sussex LXVIII.15 1909

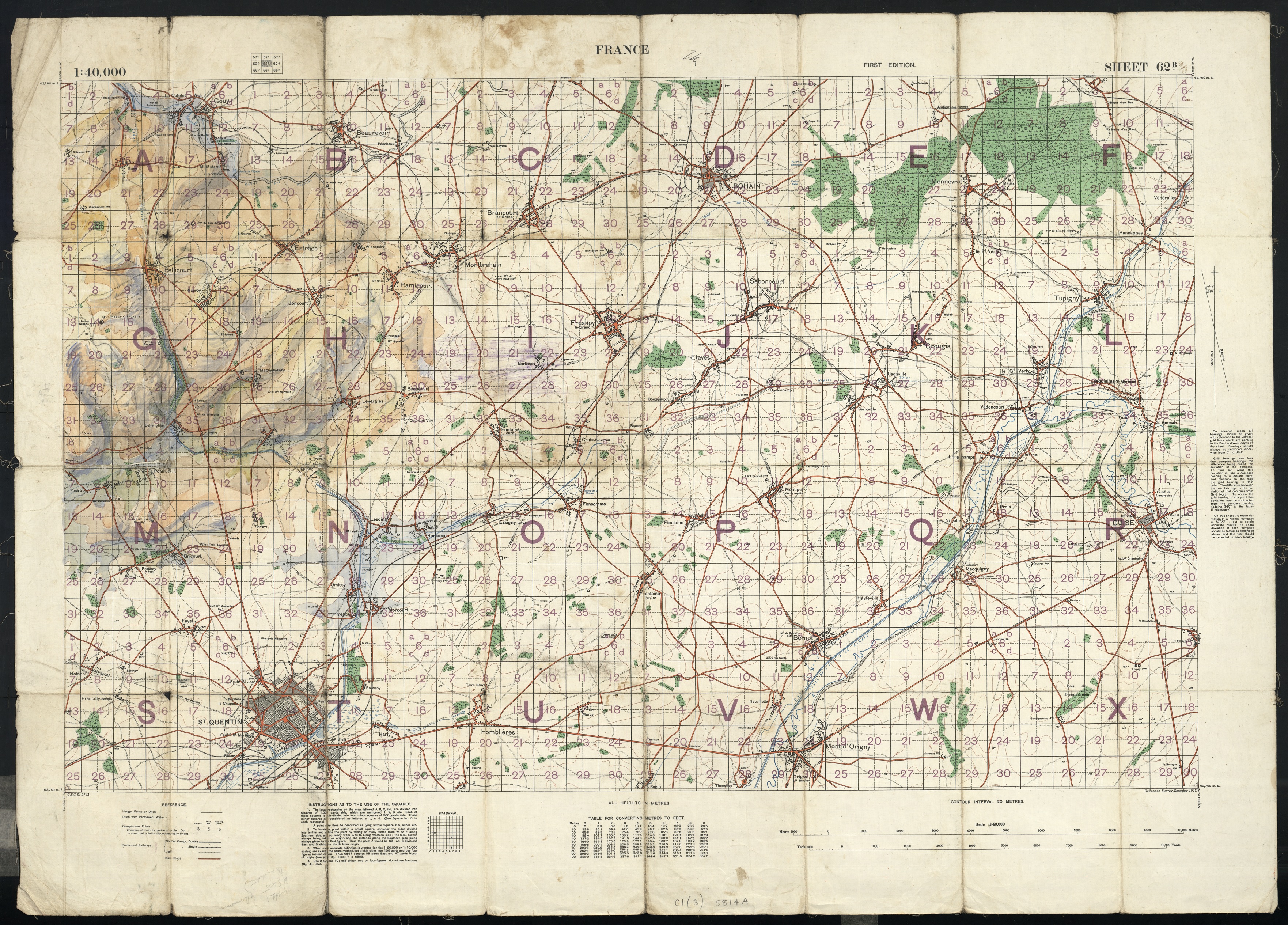

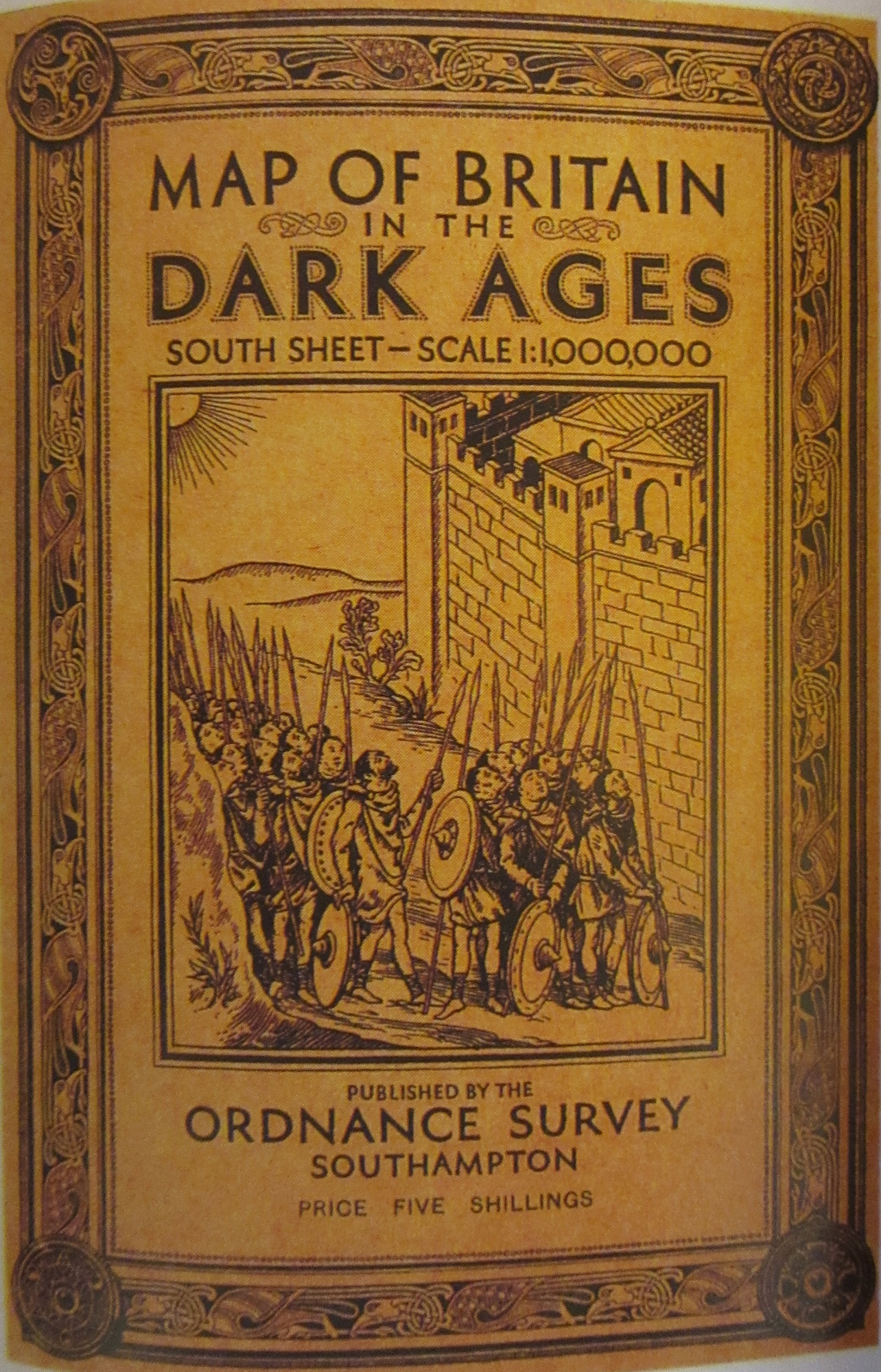

We all have maps like this. Dog-eared, well used, creased, pushed into pockets or bashed about in a rucksack. For whatever reason they show signs of wear and tear, which is an inevitable outcome considering the purpose of Ordnance Survey Landrangers and Explorers in the first place. Every crease or mark is a souvenir of a good walk or cycle.

We all have maps like this. Dog-eared, well used, creased, pushed into pockets or bashed about in a rucksack. For whatever reason they show signs of wear and tear, which is an inevitable outcome considering the purpose of Ordnance Survey Landrangers and Explorers in the first place. Every crease or mark is a souvenir of a good walk or cycle.