The different levels of mapping produced by the Ordnance Survey is astonishing. The Landranger and Explorer maps we buy in the shops are the tip of an iceberg that currently includes maps on Roman, Prehistoric and Civil War Britain, maps designed for children as well as a complete online digital service, while in the past the OS has published military, geological and administrative mapping as well as commercial maps for travellers and tourists. Amongst all these variations of themes and scales there is one set of maps that are contrary to what we imagine the purpose of map is. We expect a map to show the means to plan a journey, or a holiday or walk. In the 1930s a series of maps appeared that defied these expectations, maps that showed a land devoid of any human interference. Free of buildings, towns, cities and any transport infrastructure these maps show a landscape not seen for thousands of years.

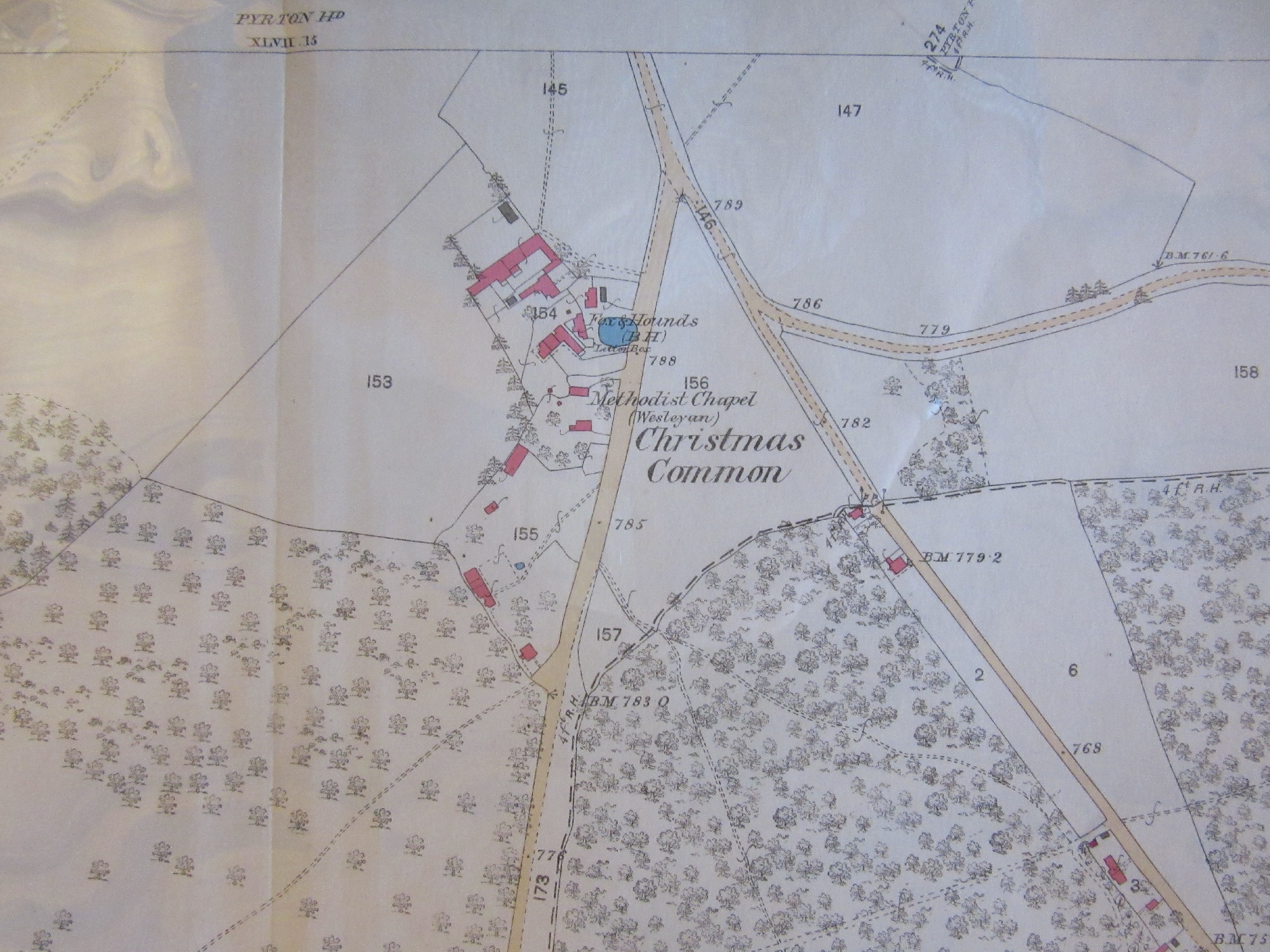

22 sheets of the 5th (relief) edition map of England and Wales were published between 1931 and 1936, and were available not only in a range of themes; coloured, physical features only, black outline and special district sheets, but also in a range of formats; paper flat, paper folded and mounted on linen. This sheet, number 146, was priced at 2 shillings and covers the Penwith Peninsula at the tip of Cornwall, a land of ancient field boundaries, roads that hug the coast and signs of early industry. It is also a land rich in prehistoric remains, though there is no indication of any of this on the map, instead you have physical features alone, contours, rivers, coastline and shading to give an idea of hills and valleys. It is a beautiful example of cartographic art. Here’s the normal edition for comparison, both maps date from 1934.

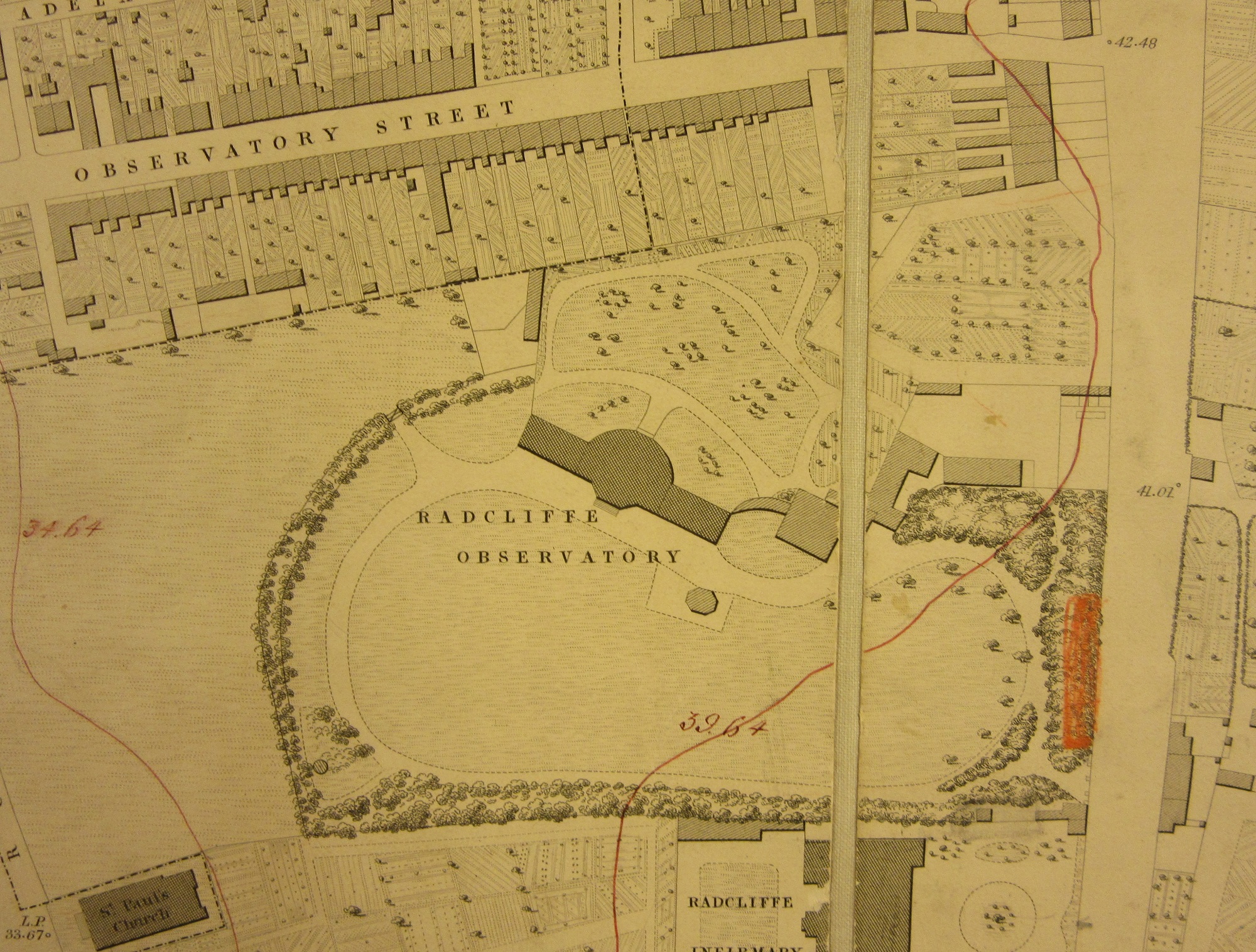

And then side-by-side extracts covering St. Ives Bay (click on maps to zoom in).

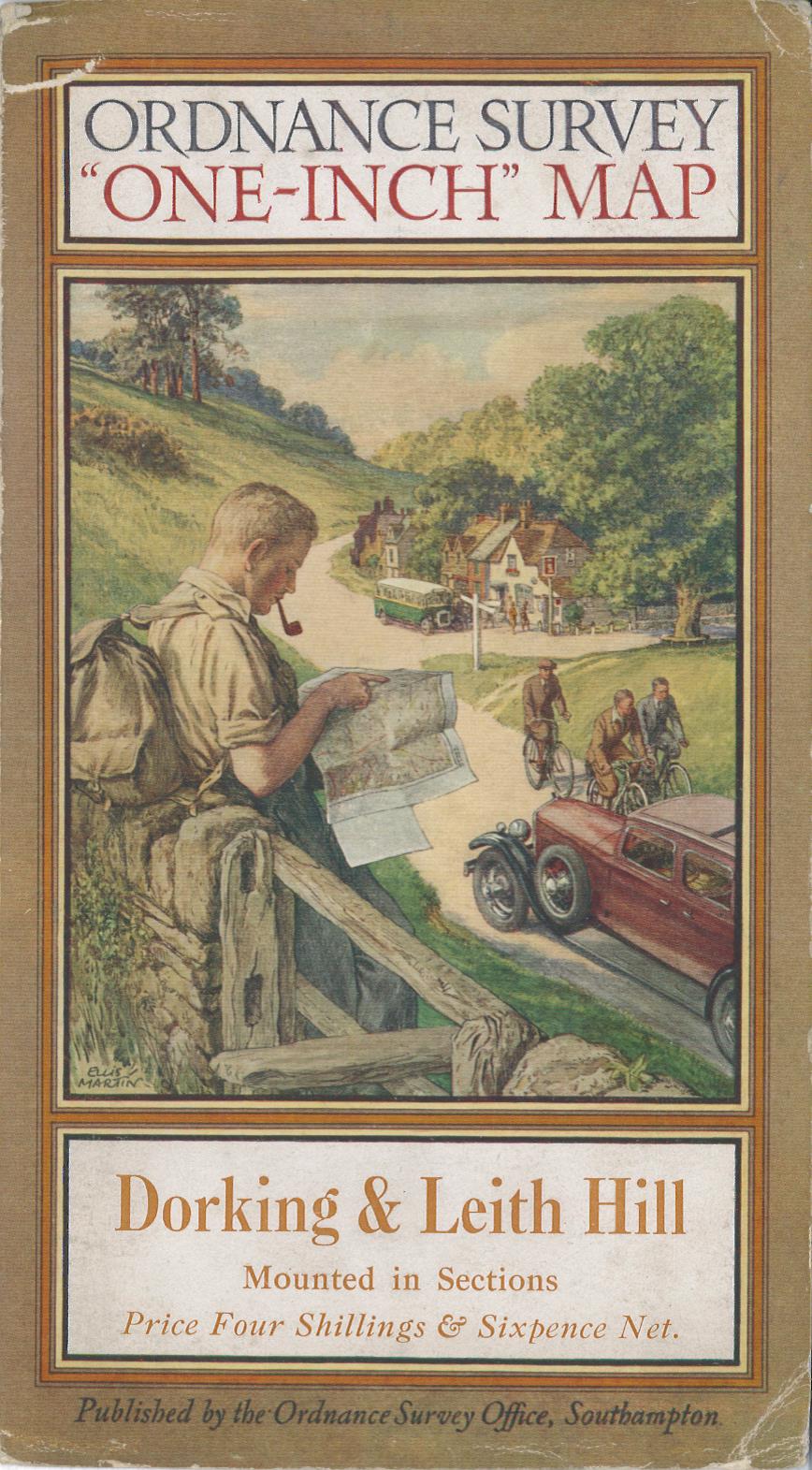

As expected the 5th edition is the fifth edition of a series of 1 inch to a mile maps first published in 1801. Weaving around these previous editions are a number of revisions, large and small sheet versions and, as mentioned already in this blog, variations on each to include outline, coloured or not and physical features mapping. When all of these are taken into consideration there as many as nine previous editions, depending on how you count all published versions (and you could make an argument for more if you include military and geological maps as well). The covers were also beginning to be part of the whole package, with trained artists employed to capture the post-war spirit of the outdoors as a leisure activity, be it cycling or walking. With the 5th edition each cover had a similar design, with sheet number and name and a small portrait of a hiker. Soon covers would become more individual, reflecting the area mapped, and were miniature works of art in themselves (more on OS cover art can be found here)

Fifth (Relief) Edition England & Wales, sheet 146 1934. C17 (30c) and C17 (30b).

We all have maps like this. Dog-eared, well used, creased, pushed into pockets or bashed about in a rucksack. For whatever reason they show signs of wear and tear, which is an inevitable outcome considering the purpose of Ordnance Survey Landrangers and Explorers in the first place. Every crease or mark is a souvenir of a good walk or cycle.

We all have maps like this. Dog-eared, well used, creased, pushed into pockets or bashed about in a rucksack. For whatever reason they show signs of wear and tear, which is an inevitable outcome considering the purpose of Ordnance Survey Landrangers and Explorers in the first place. Every crease or mark is a souvenir of a good walk or cycle.