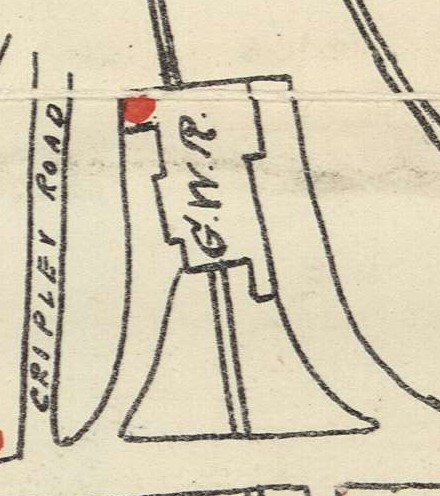

In the mid-nineteenth century Oxford was still a small town dominated by the University but surrounded on three sides by water which had the effect of curtailing expansion of decent housing but by 1850 a series of circumstances led to the development of the North Oxford suburbs, in the St Giles parish. The population of the town grew sharply between 1821 and 1841, the Great Western Railway arrived in 1844 and, later in the 1870s, University fellows were allowed to marry thus leaving their college lodgings to live nearby. St John’s College owned a large tract of land, known as St Giles Fields which it had acquired in 1573 from George Owen, physician to Henry VIII to the north of the town. The middle class of professionals with disposable wealth were growing, housing was required so the time was ripe to develop this land.

The first attempt came in 1852 when architect Samuel Lipscomb Seckham (who went on to built Bletchley Park) was asked by the College to submit drawings for a new suburb to the north of the town. This terraced crescent of handsome Italianate houses with communal garden, rather in the style of Bath, became Park Town, the earliest planned development in Oxford.

This was the forerunner to the later developments of Walton Manor and Norham Manor. Once again Seckham produced this drawing for the what was to be called Walton Manor. As you can see most of the large villas are in his preferred Italianate style except for one which oddly shows elements of Victorian Gothic. This was not as successful with only one of the residences being built – still currently at 121-123 Woodstock Road.

The Walton Manor estate plan was revived in 1859 with Seckham still in charge but with the plan considerably changed. The following year an adjoining piece of land was offered for sale to become the Norham Manor estate by St John’s College. Initially Seckham was to manage both estates but William Wilkinson an architect from an auctioneering family of Witney, nearby, was awarded the supervision of Norham Manor. Wilkinson’s practice was prospering but involved church restorations and work for the rural gentry on domestic and agricultural buildings rather than villas and terraces.

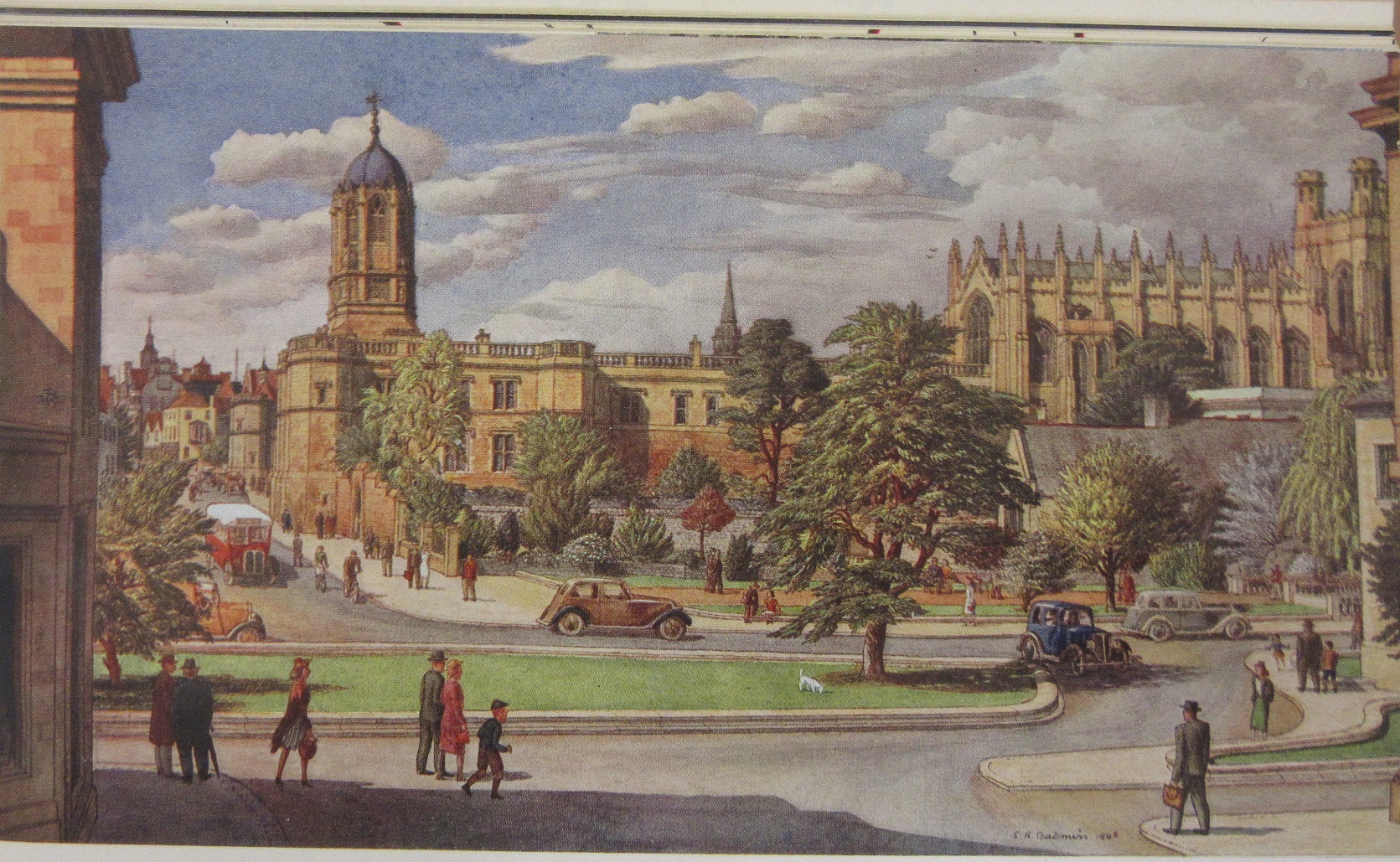

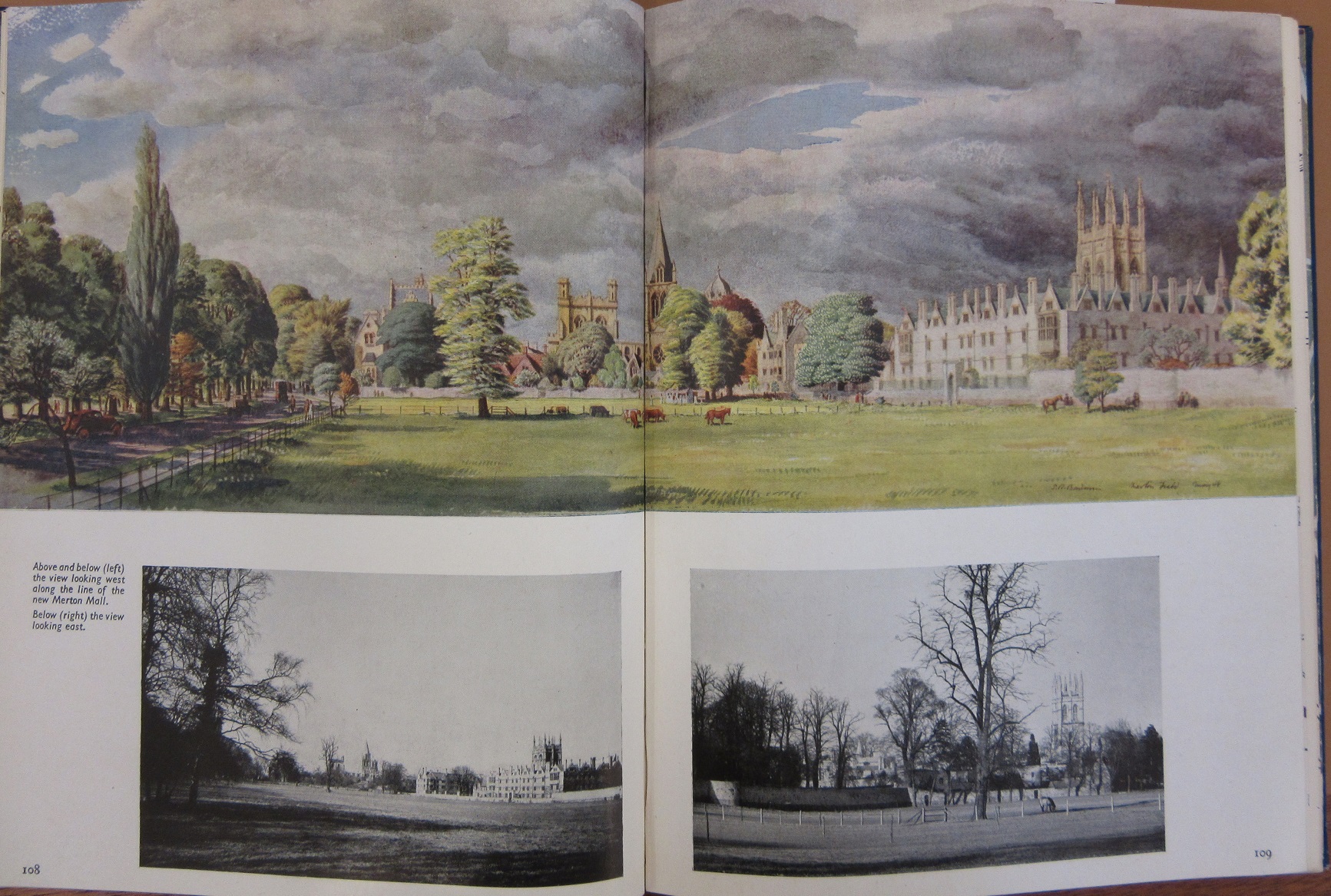

His vision for the estate can be seen clearly from this view which was painted by him in c.1860. In this incredibly detailed watercolour you can see it has been conceived as a gated community of large suburban villas for the wealthy middle classes. By the mid-1860s Wilkinson had taken over the whole of the North Oxford suburb development and was building his pièce de resistance, the Randolph Hotel (1862-64). This Oxford landmark is still standing in its Gothic splendour.The large individual residences of both Norham Manor and Walton Manor were largely complete by 1870 so attention was turned to the smaller semi detached and terraced houses which give the area its character today. However, not everyone was a fan – Thomas Sharp of Oxford Replanned (blog here) felt the area was an ‘architectural nightmare’.

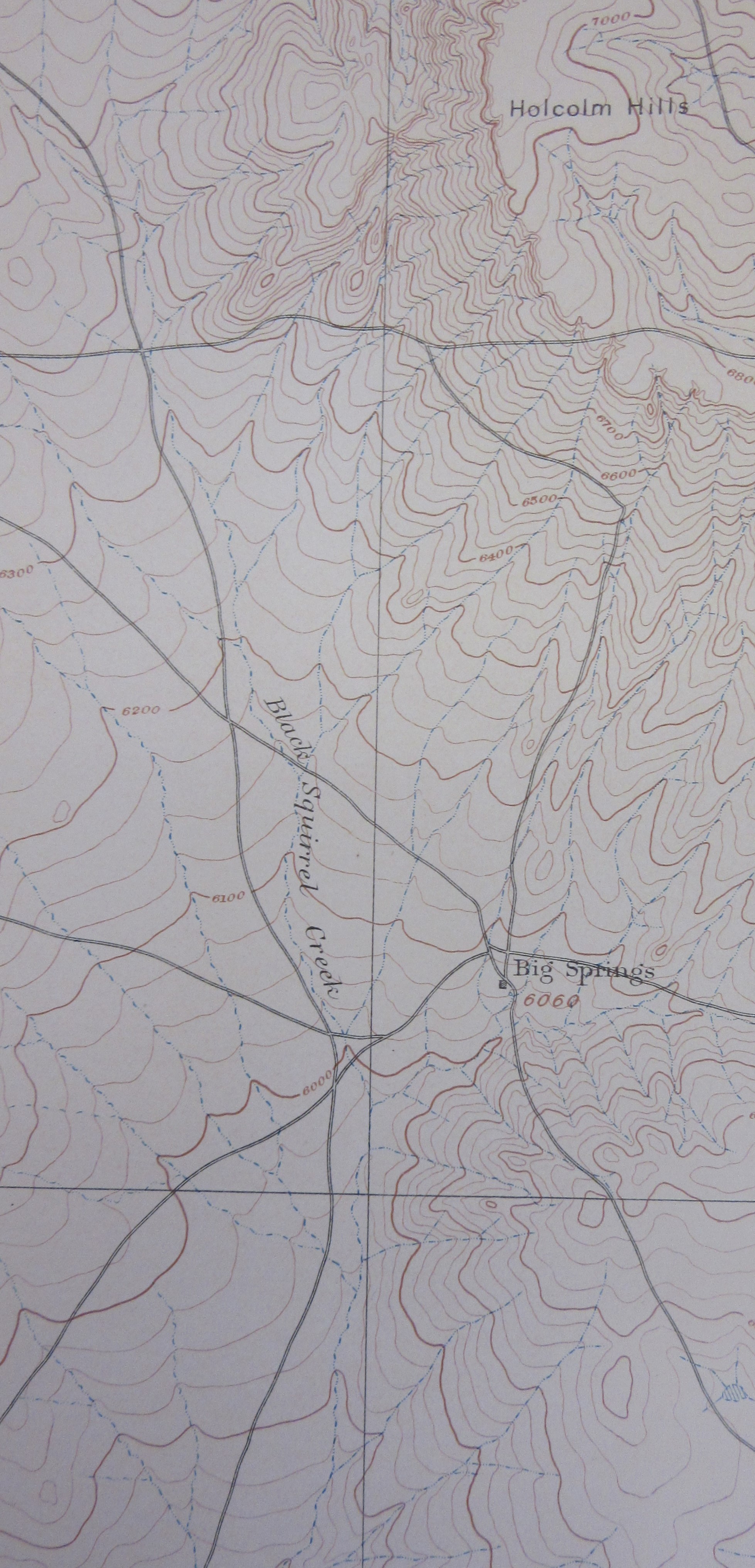

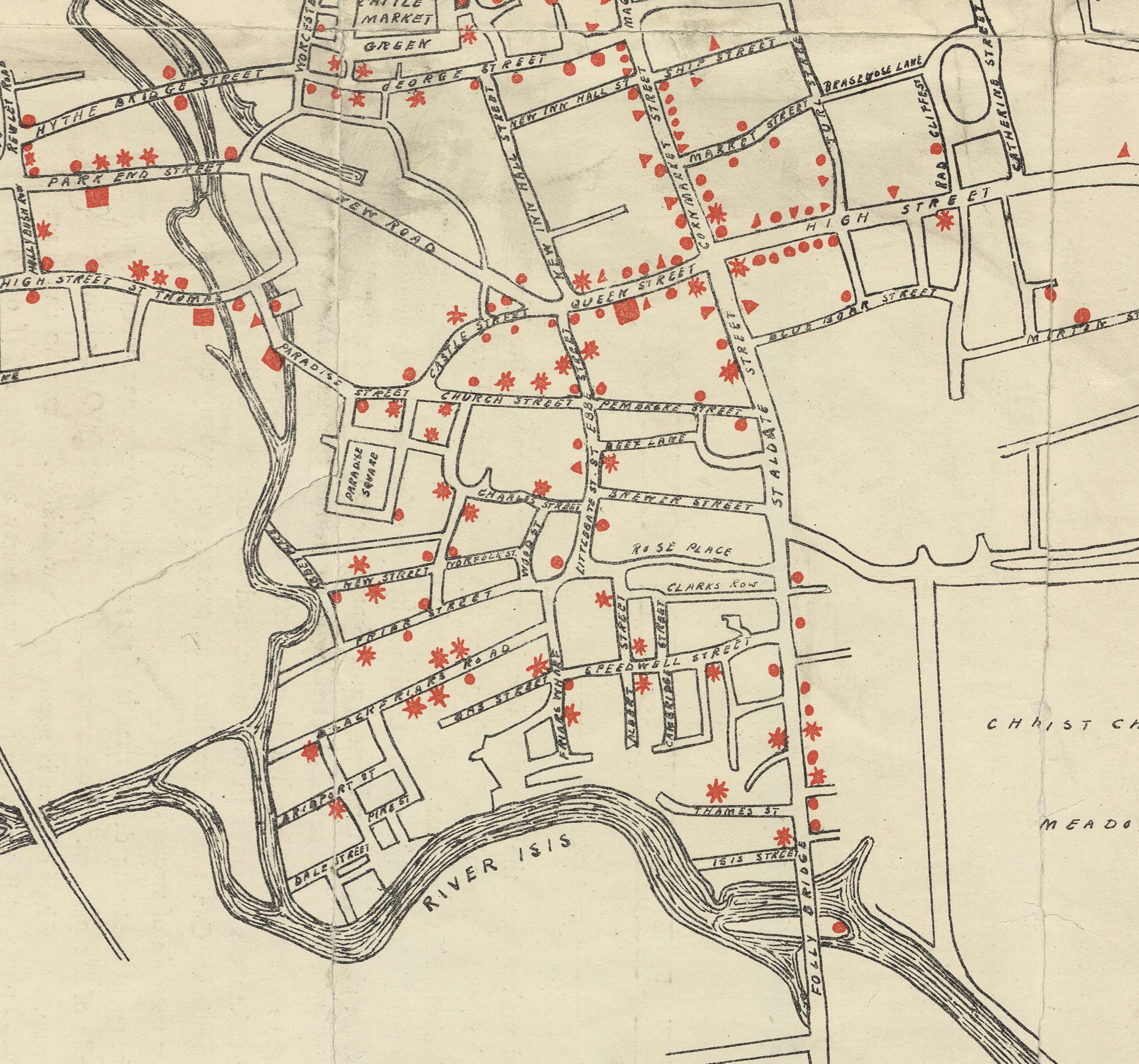

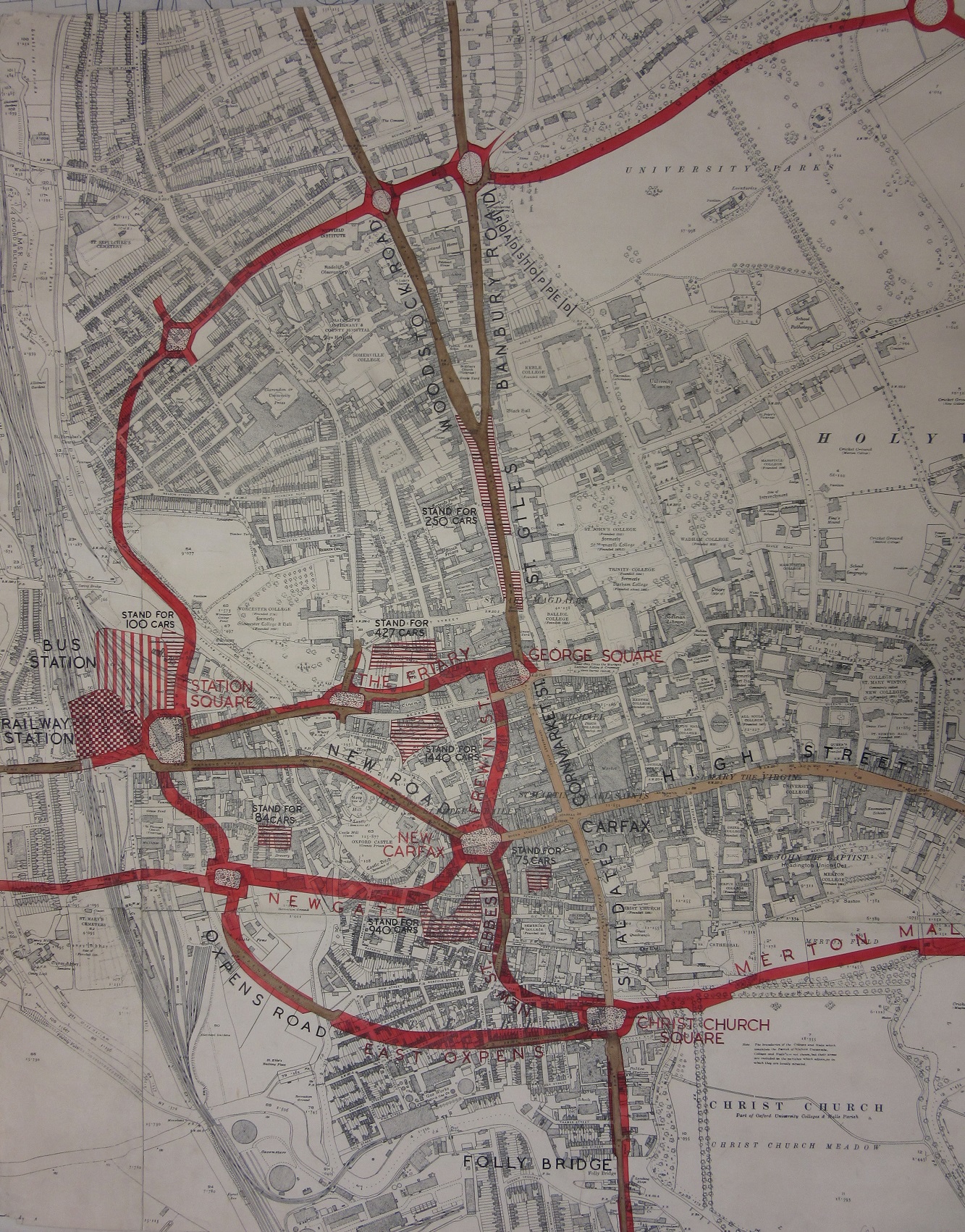

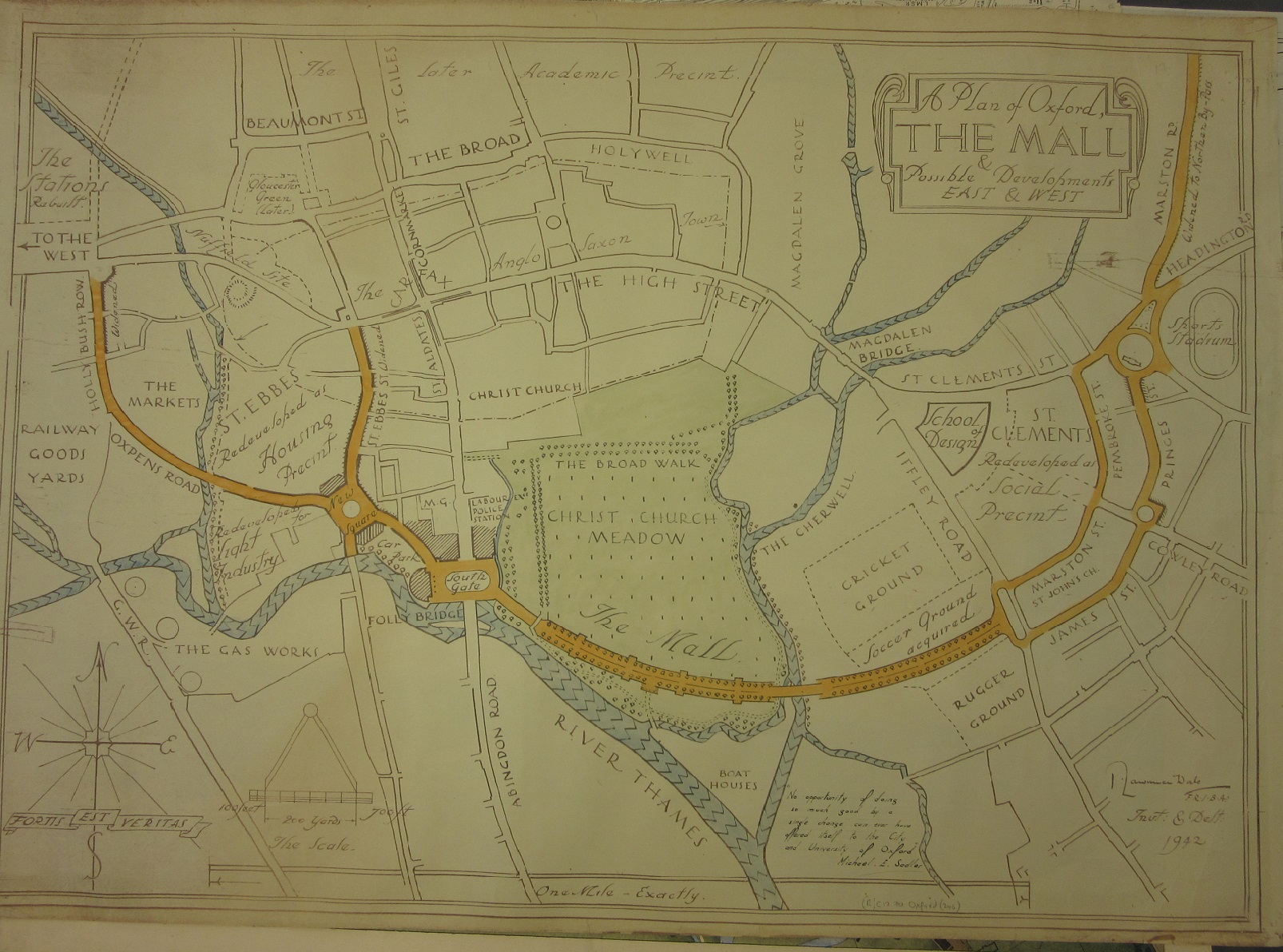

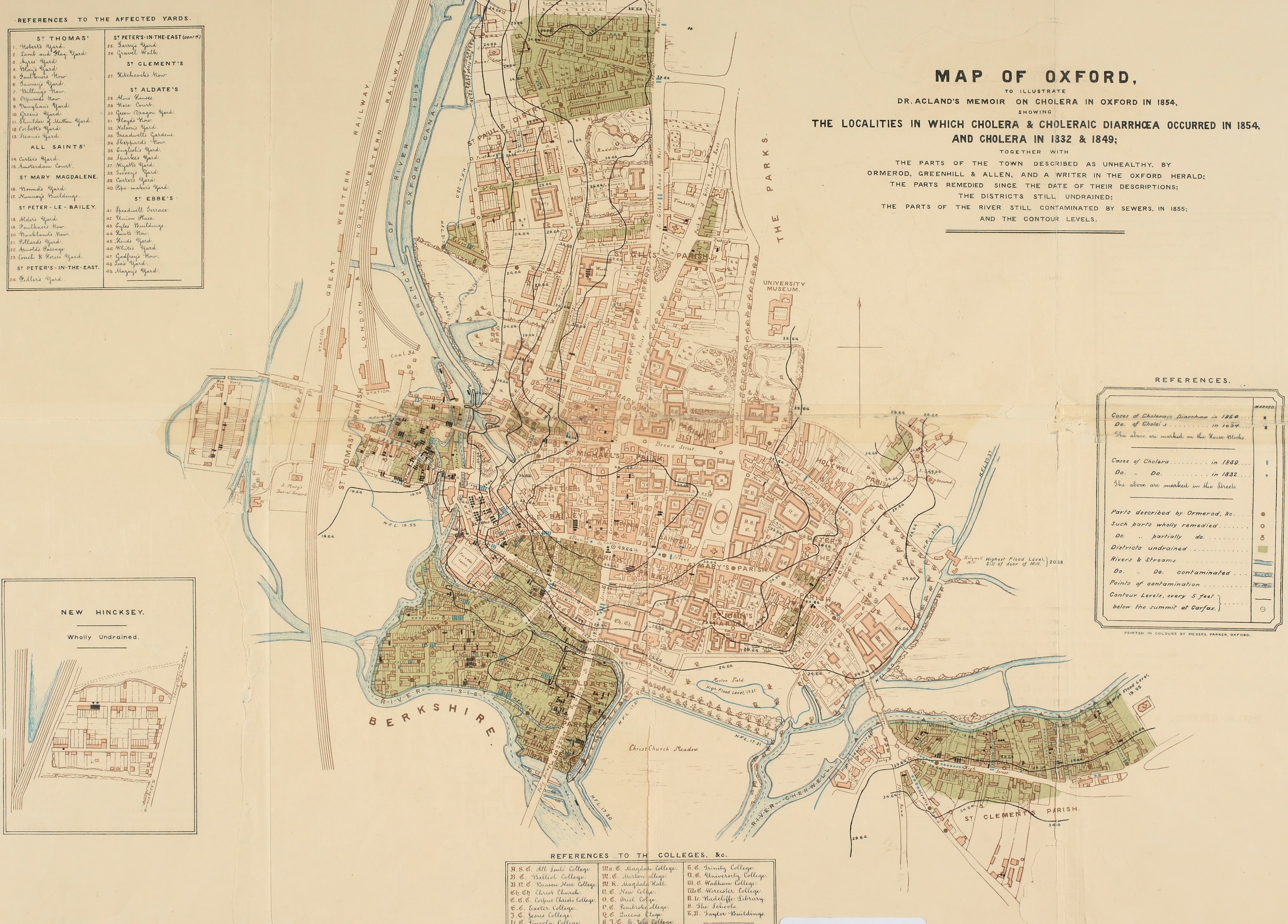

The spread of development can be seen clearly in the map record.

Ordnance Survey 1st edition 25” Oxfordshire XXXIII.15 1876

Bird’s eye view of the Walton Manor Estate [1854] C17:70 Oxford (103)

Proposed Norham Manor Estate [c.1860] MS. Top. gen. a. 22

Plan of an Estate called Park Town [1853] C17:70 Oxford (30)

T. Jeffreys. Plan of the university & city of Oxford 1767 Gough Maps Oxfordshire 17

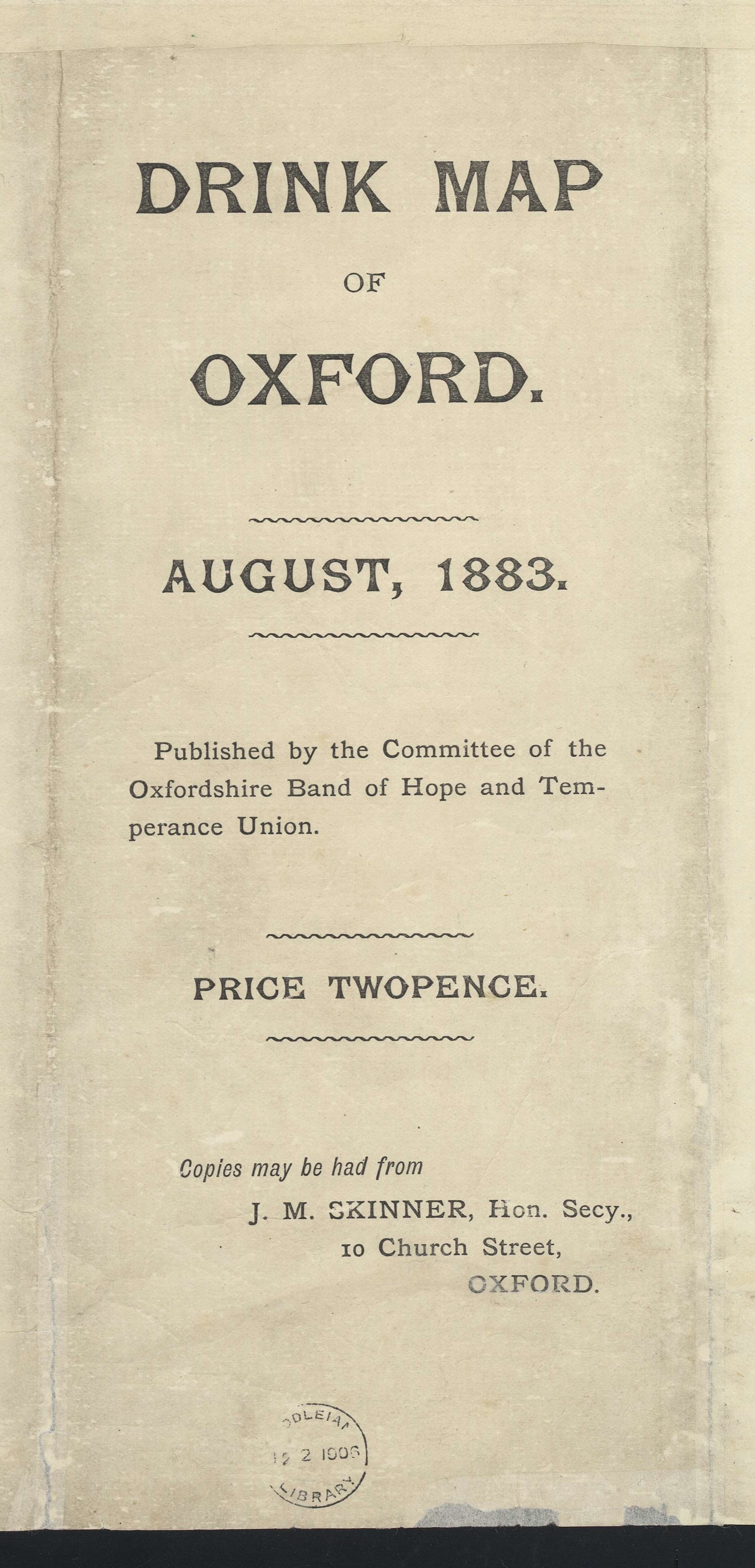

Alden’s new plan of the city and university of Oxford 1888 C17:70 Oxford (5)

Plan of Oxford 1902 C17:70 Oxford (6)

Plan of the city and university of Oxford [1949] C17:70 Oxford (36)

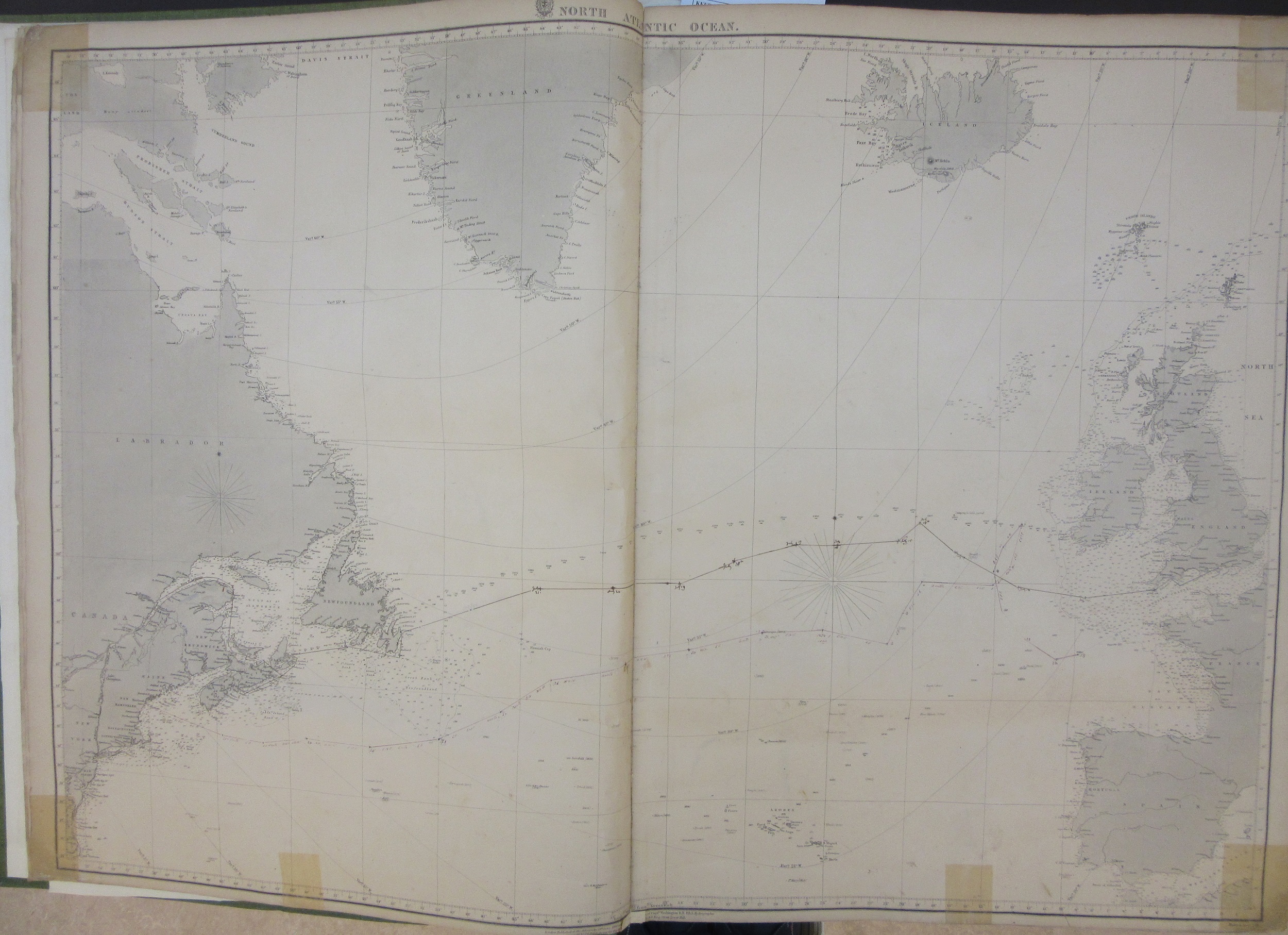

An extract from the chart showing the route taken to Quebec, sailing through the wonderfully named Gut of Canso (also called the Gut of Canseau) between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

An extract from the chart showing the route taken to Quebec, sailing through the wonderfully named Gut of Canso (also called the Gut of Canseau) between Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

In the year after the voyage a book was privately published by Gardner D. Engleheart. ‘Journal of the progress of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales through British North America and his visit to the United States… (203 a.333)’. The book includes illustrations and text about the visit and, helpfully for the purpose of this blog and identifying the map, a log of the journey out giving positions at noon on each day as well as a number of different diary entries from the voyage. So for instance we learn that the Royal Yacht (the Hero) ‘with the Prince Consort sailed at 4 a.m.’, presumably to catch the tide. Then, far more dramatically, from a different diary on the 12th ‘Man overboard! The gun-room steward jumped out of one of the ports, in a fit of temporary insanity, and was drowned! Every effort was made to rescue him, but he would not be saved.’

In the year after the voyage a book was privately published by Gardner D. Engleheart. ‘Journal of the progress of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales through British North America and his visit to the United States… (203 a.333)’. The book includes illustrations and text about the visit and, helpfully for the purpose of this blog and identifying the map, a log of the journey out giving positions at noon on each day as well as a number of different diary entries from the voyage. So for instance we learn that the Royal Yacht (the Hero) ‘with the Prince Consort sailed at 4 a.m.’, presumably to catch the tide. Then, far more dramatically, from a different diary on the 12th ‘Man overboard! The gun-room steward jumped out of one of the ports, in a fit of temporary insanity, and was drowned! Every effort was made to rescue him, but he would not be saved.’