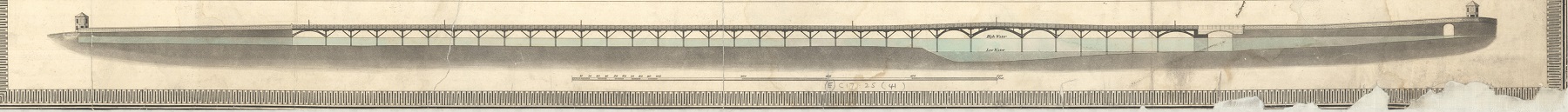

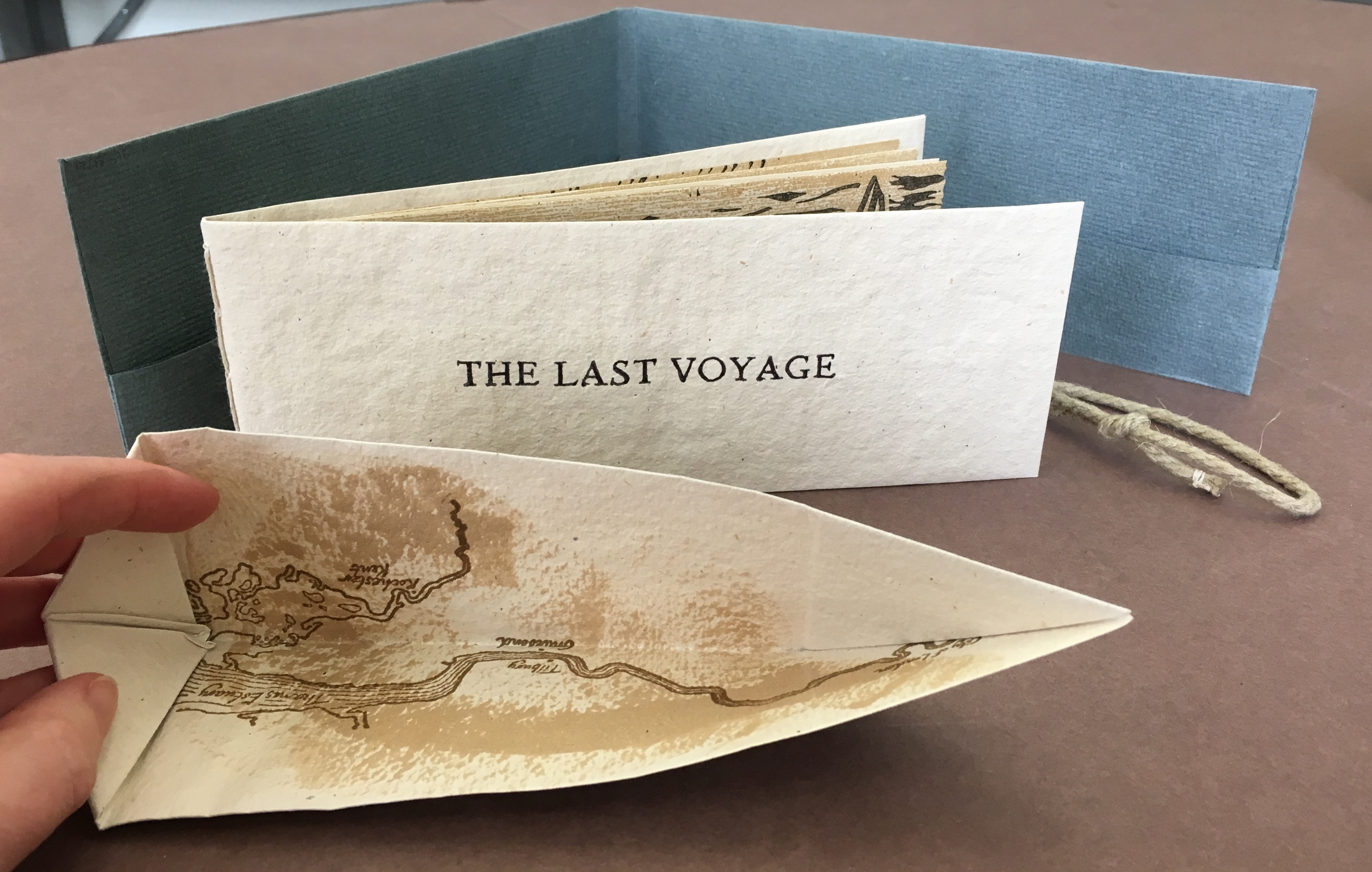

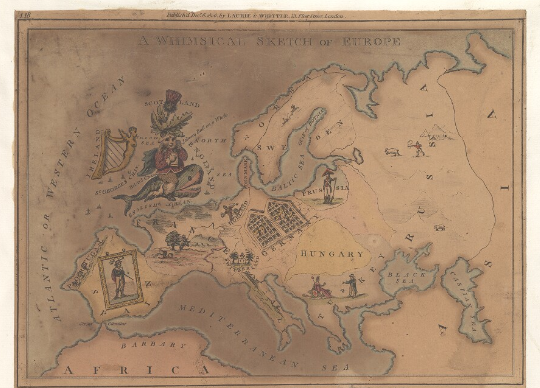

December 11th is United Nations International Mountain Day, so we’re celebrating with this unusual Alpine panorama. This map of an Alpine road appears at first glance to be a view of mountains reflected in water. Closer examination shows that a road runs along the centre of the map; it is printed on a long strip, folded concertina style, with the road shown as a straight line and panoramic views of the mountains on either side. Unusual formats like this have been used in other Alpine maps, to address the challenge of portraying a long vista on paper; a panorama of the view from the summit of Mont Blanc featured in an earlier blog post.

The map was drawn by the poster artist Louis Guerry, and published in Grenoble in 1896 by Joseph Baratier. It shows the road between Vizille and Briançon in France, close to the border with Italy. Side roads wind off into the mountains and small Alpine settlements are marked along the way. Highest and most dramatic of the mountains is La Meije, with five peaks and glaciers flowing down either side; it was one of the last major Alpine peaks to be climbed, and also features on the cover illustration (above). Other names, such as Galibier and Alpe d’Huez, will be familiar to fans of the Tour de France cycle race; the road up to Alpe d’Huez did not at this time reach all the way to Huez itself, which appears as a high isolated village.

This copy came to the library recently, a donation from the grandson of Thomas Arthur Rumbold. When Rumbold joined the Alpine Club in 1902 he was their youngest member. His application shows an impressive list of climbing experience from the late 1890s; it includes mountains in the French, Italian and Swiss Alps, many of them “without guides”, and rock climbing in the Allegheny Mountains in Virginia. The map was donated along with Rumbold’s trench maps from his time serving in WWI, which were a welcome addition to our collection. Happily, Rumbold survived the war; he went on to become Secretary to Sir George Schuster, Governor of the Bank of England. He also found time to enjoy more Alpine fun in the snow (see below) and eventually became the oldest member of the Alpine Club!

Thomas Rumbold and friends enjoying St Moritz. Photo shared by his grandson.

The map folds into a small cover with a conventional route map on the back.

The map when extended is over 2 metres long. As we admired it in the Map Room office, we reflected that in these times of Covid restrictions it is rare to find a map so long that more than one person can look at it at once while social distancing.

Dépliant Alpestre : Excursion en Oisans. Projection sur 100 kilometres des sommets du Massif / dessiné par Louis Guerry. Grenoble : Joseph Baratier, [1896]. C21:44 (48)

You can see more about this map at the website of the Bibliotheque Dauphinoise.