Few maps manage to combine cartography, history and sheer bonkersness with such good effect as Prussia pausing, or the accurate armistice demarcation line. In the map the neck and face of a lion are overprinted on a map of France like some animalistic Victorian ectoplasm to show the areas occupied by German forces at the end of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71.

Prussia pausing…1871. C21 (110)

A brief bit of history. Strengthened following victory against Austria in 1866, combined German states invaded and defeated France in a war that started in the summer of 1870 and was won by early 1871. At the start of the war the German forces fought as the North German Confederation, of which Prussia was the largest and most dominate state. The end of the war led to the forming of a united Germany and the wide-spread copying of the military tactics used. Soon after the defeat the English publisher Edward Stanford published Prussia pausing… on Valentine’s Day 1871. The critical nature of the map (Attention is drawn to the extraordinary coincidence of the Armistice boundaries representing the outlines of a carnivorous animal typical of the relentless veracity of Prussia…) wasn’t mirrored in political circles, who still viewed France as the main competitor in global trade and empire, while, remarkably considering future events, not looking on Germany as being strong enough to offer a threat to British interests.

A lion traditionally represented strength and courage but also cruelty and death. From the concept of strength comes another use of the lion, as a symbol of imperialism or statehood. This is one of the reasons for one of the most famous of all zoomorphic (as in the use of animals to suggest or represent a non-animal action) maps, the Leo Belgicus.

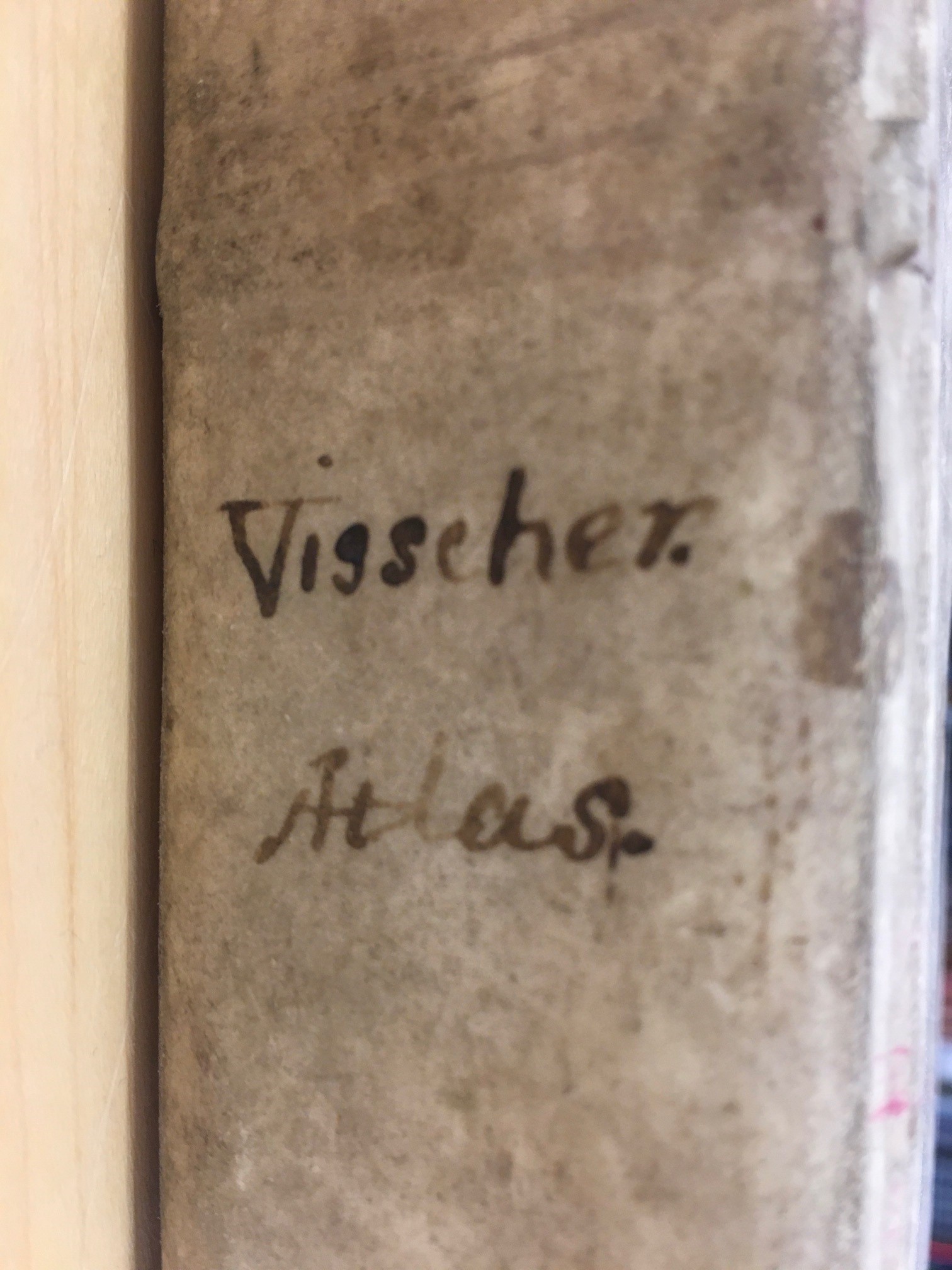

Leo Belgicus, facsimile of 1650 edition, C27 (146)

There are a number of versions of this famous map, dating from the late 1500s to the mid 1600s, and the lion could be shown as either fighting or not depending on the current state of the Dutch war with Spain to gain independence. The lion was drawn in a way that represented the areas we know now as the Netherlands and Belgium and, more importantly, was represented on the arms of some of the seventeen provinces that made up the Low Countries.

Looking through a box of uncatalogued maps, plots and diagrams I came across several manuscript architectural plans of the Midland Grand Hotel, London. Now named the St Pancras Hotel it is an iconic landmark on the Euston Road next to that other celebrated edifice of red brick, the British Library. The plans, drawn to show the girders, were by engineer Richard Moreland of Old Street in 1867 at a scale of 10 feet to 1 inch (1:120). You can see all of the modern internal features with the Grand Staircase and the popular Ladies Coffee Room. There are even manuscript pencil marks denoting dimensions which indicate these were some sort of working drawings.

Looking through a box of uncatalogued maps, plots and diagrams I came across several manuscript architectural plans of the Midland Grand Hotel, London. Now named the St Pancras Hotel it is an iconic landmark on the Euston Road next to that other celebrated edifice of red brick, the British Library. The plans, drawn to show the girders, were by engineer Richard Moreland of Old Street in 1867 at a scale of 10 feet to 1 inch (1:120). You can see all of the modern internal features with the Grand Staircase and the popular Ladies Coffee Room. There are even manuscript pencil marks denoting dimensions which indicate these were some sort of working drawings.