This panorama of the Manchester Ship Canal was created to mark its opening by Queen Victoria in 1894; the culmination of more than 12 years of campaigning and construction work. This section at the bottom of the map shows the docks and the canal itself which runs almost into the heart of the city of Manchester.

For much of its length the canal is a straight, wide channel; this section from the middle of the panorama shows it cutting out the loops of the River Mersey between Manchester and Runcorn. Beyond this point the canal runs alongside the river, before joining it on the estuary past Liverpool to the sea. The title makes clear that this was a local production, designed, lithographed (printed) and published by J. Galloway & Son of Manchester. Undoubtedly the finished canal, allowing direct access to the city for large cargo ships, was a source of civic pride.

The plan to create a shipping canal linking Manchester to the sea had first been proposed in the early 1880s, in an attempt to reduce costs for traders in Manchester. This simpler, uncoloured panorama was published in 1883 as part of the campaign, surrounded by quotes from local dignitaries (such as the MPs Jacob Bright and William Agnew, and the Mayor of Salford) and from supportive newspapers. It argues that “the general industries in this region have to bear excessive taxation in carriage of their merchandise to and from the sea,” referring to the charges imposed by the port of Liverpool and cost of railway transport. It was allegedly cheaper to transport cotton from Liverpool to Glasgow than from Liverpool to Manchester, for example. The proposed route is represented clearly but the campaigners have cunningly foreshortened the straightest part of the canal, perhaps to make it look shorter and easier to achieve. However, as one of the notes on the map points out, the much larger Suez Canal had recently been constructed, to great admiration. So the Manchester Ship Canal was a viable proposition. The plan above was made in the late 1880s, probably once the canal was under construction. The section here shows the relative shallows of the Mersey estuary bypassed by the canal. It is surrounded by advertisements for huge a variety of products, including toothpaste and medicines, and domestic items such as sewing machines and locks; a detailed inset plan of the Manchester and Salford Docks promotes both furniture and ale.

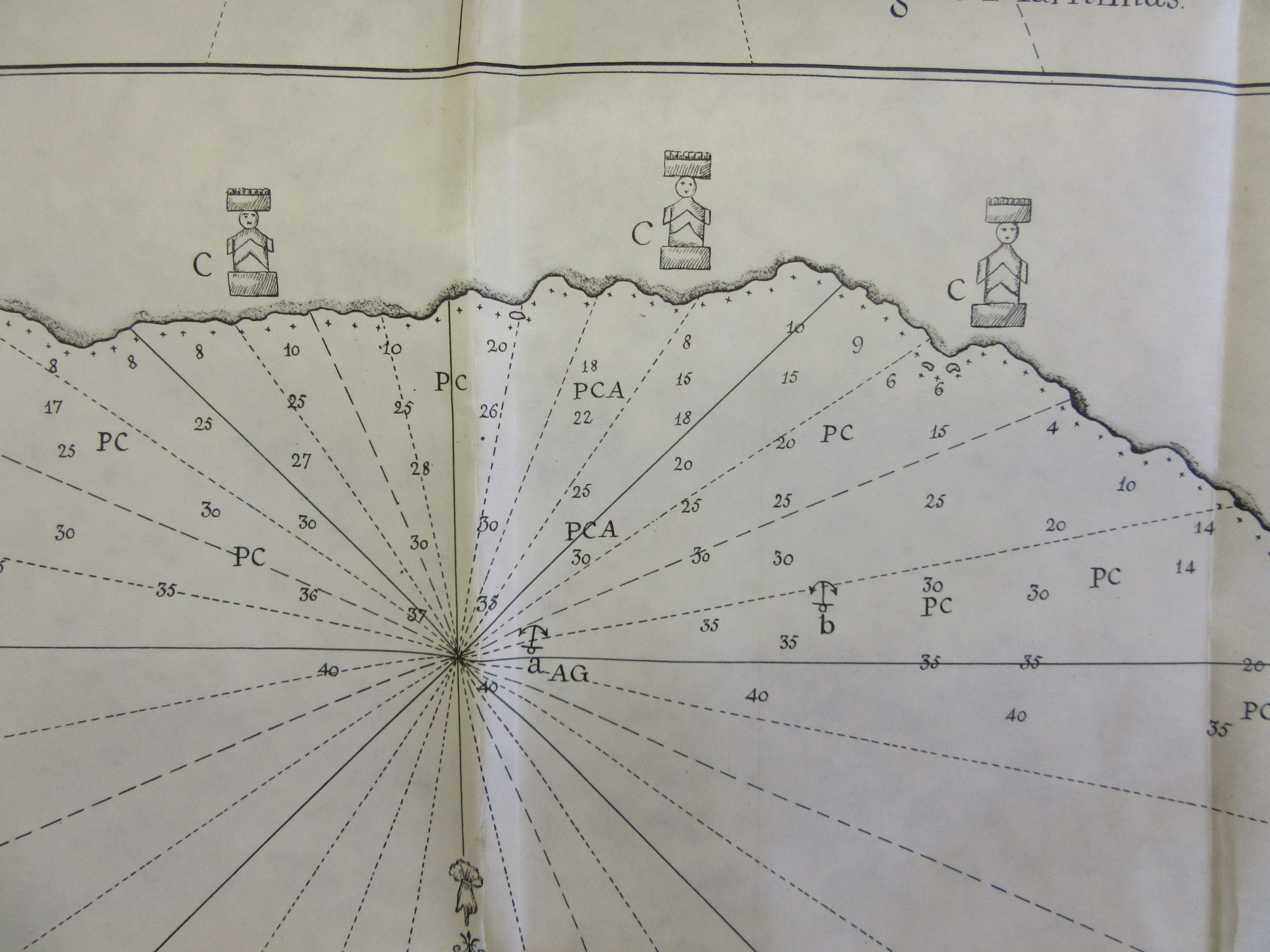

The plan above was made in the late 1880s, probably once the canal was under construction. The section here shows the relative shallows of the Mersey estuary bypassed by the canal. It is surrounded by advertisements for huge a variety of products, including toothpaste and medicines, and domestic items such as sewing machines and locks; a detailed inset plan of the Manchester and Salford Docks promotes both furniture and ale.

What of the connection with September? The well known nursery rhyme and singing game, “The big ship sails on the Alley Alley-Oh” is popularly believed to refer to the Manchester Ship Canal. The song refers to a ship setting out “on the last day of September,” which comes to grief and sinks “to the bottom of the sea”. Various interpretations of the song have been suggested: one is that a ship that was contracted to set out in September might be under financial pressure to do so even the weather was unfavourable or the ship not seaworthy; it may also have been a reference to the last date a ship could expect to set out and reach Canada before the St Lawrence River began to be blocked by ice. Whatever the explanation, the unhappy ending of the ship does not seem to have deterred generations of children from singing the song.

Panoramic map of the Manchester Ship Canal / designed, lithographed and published by J. Galloway and Son, Manchester, 1894. C17:3 (14)

Bird’s eye view of the Manchester Ship Canal, 1883. C17:3 (49)

Manchester ship canal – general plan of canal and district. Revised. [1889?] C17:3 (13)

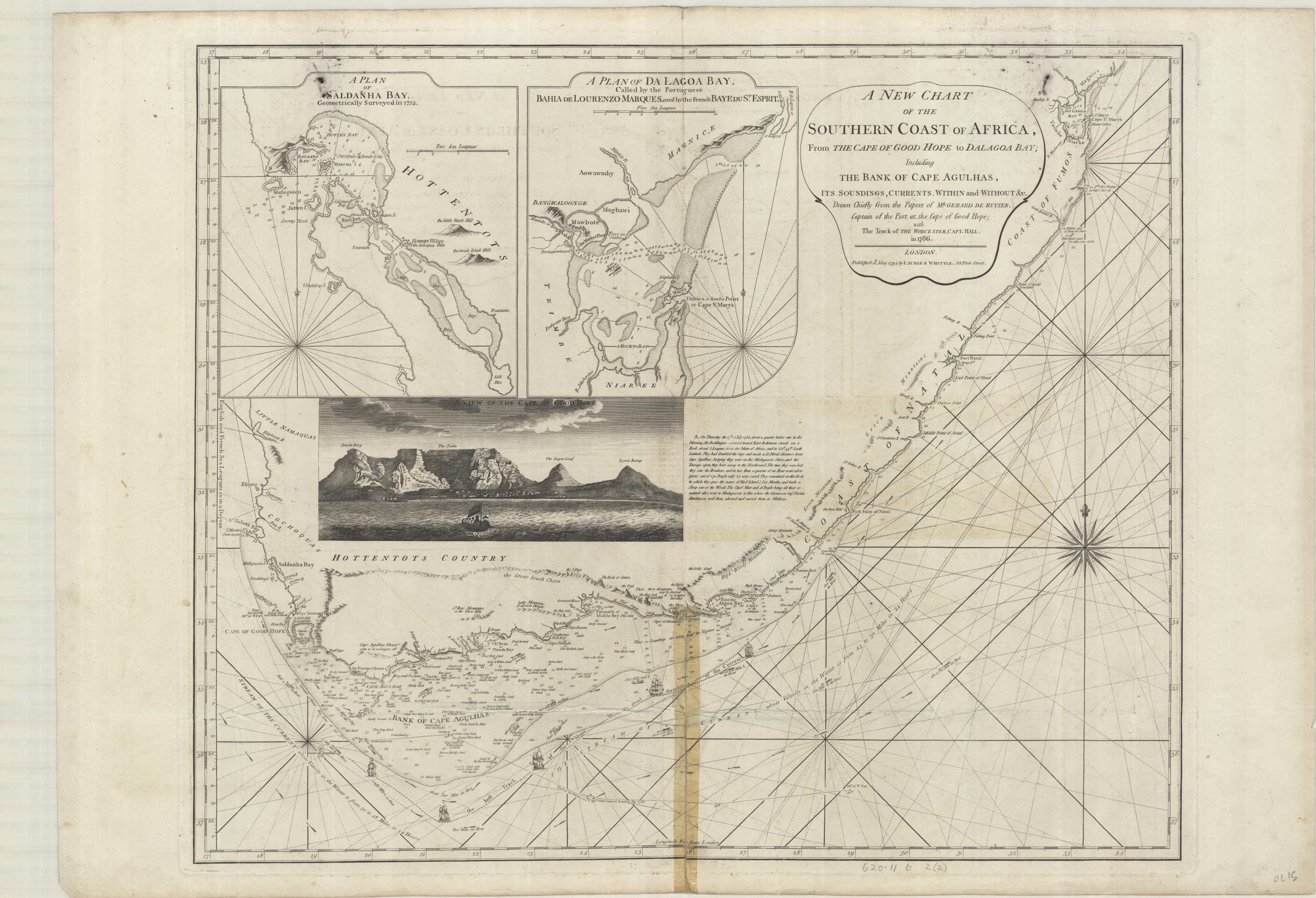

The book describes how the ship set sail on April the 23rd, 1755, taking seven weeks to get to the Cape. Then disaster strikes early on Thursday, July 17th, as the ship is wrecked on Bird Island. Despite breaking an arm and being being told by the Captain that ‘we should all perish’ Webb managed to get to Bird Island and eventually take part in the journey on a boat made from the wrecked remains 6 months later to Madagascar. On this extract from the map Bird Island is the central rock A while the rock marked F is believed by Webb to be the one the ship first hit before being driven by the high seas onto Bird.

The book describes how the ship set sail on April the 23rd, 1755, taking seven weeks to get to the Cape. Then disaster strikes early on Thursday, July 17th, as the ship is wrecked on Bird Island. Despite breaking an arm and being being told by the Captain that ‘we should all perish’ Webb managed to get to Bird Island and eventually take part in the journey on a boat made from the wrecked remains 6 months later to Madagascar. On this extract from the map Bird Island is the central rock A while the rock marked F is believed by Webb to be the one the ship first hit before being driven by the high seas onto Bird.

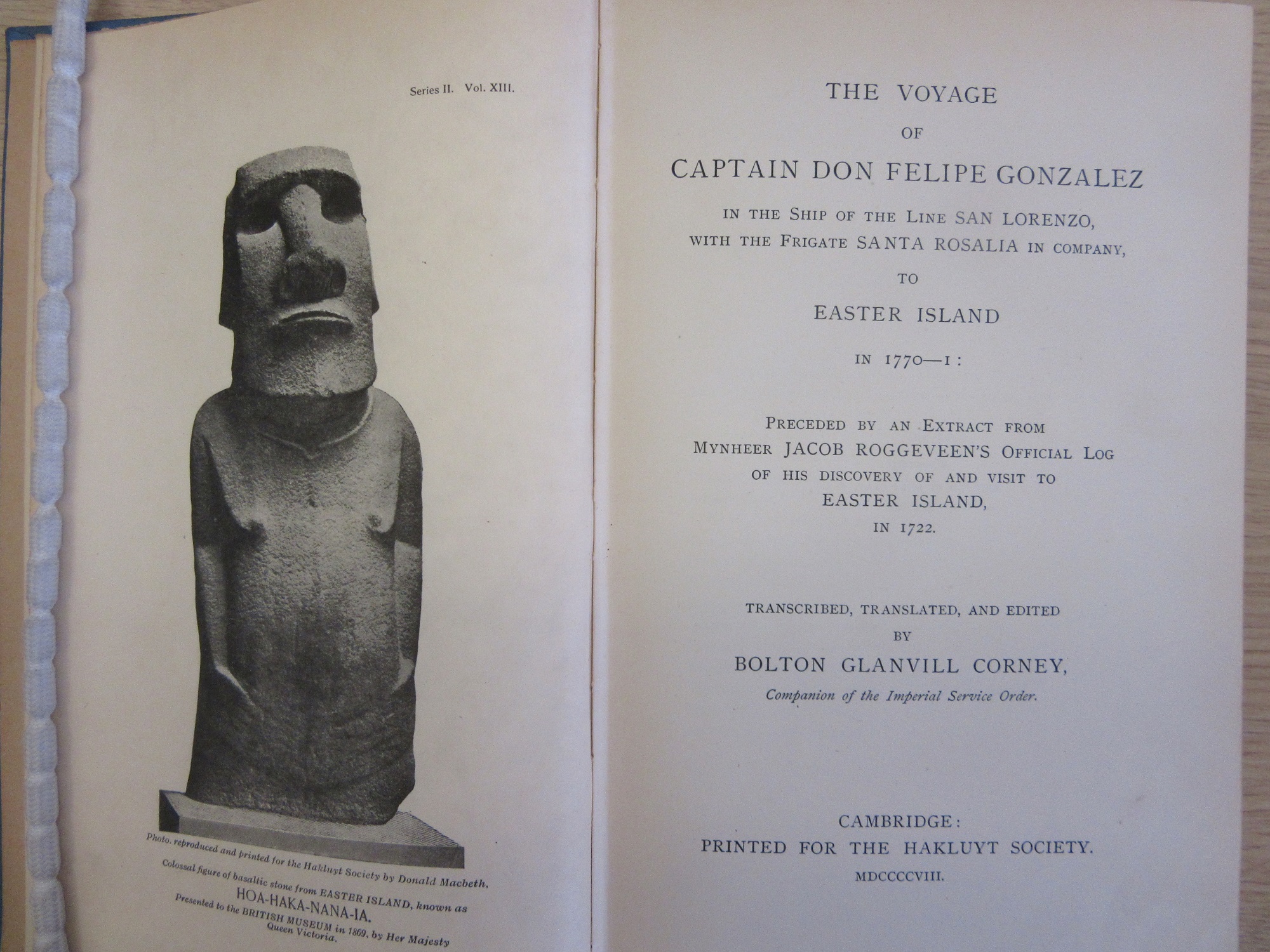

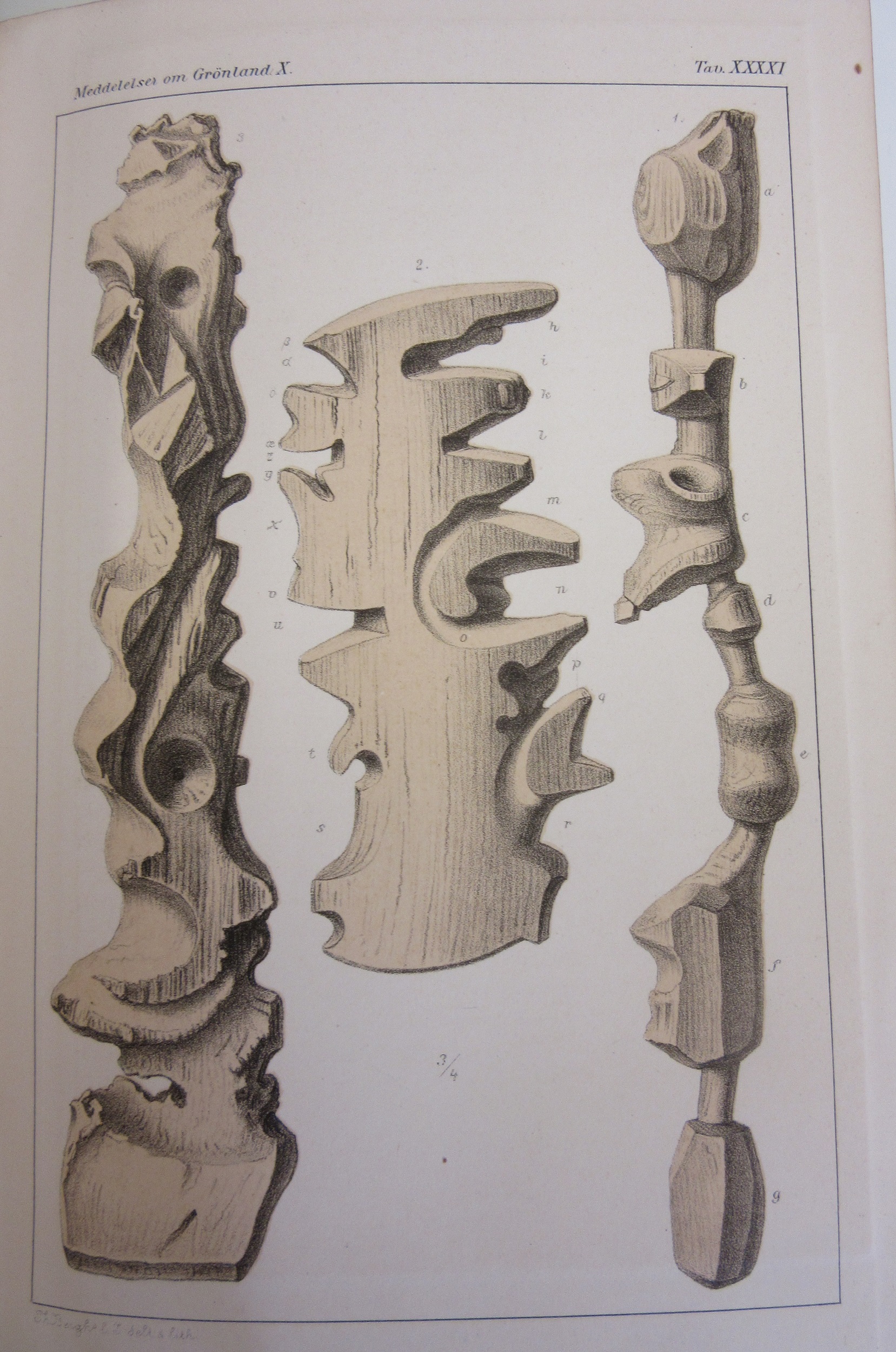

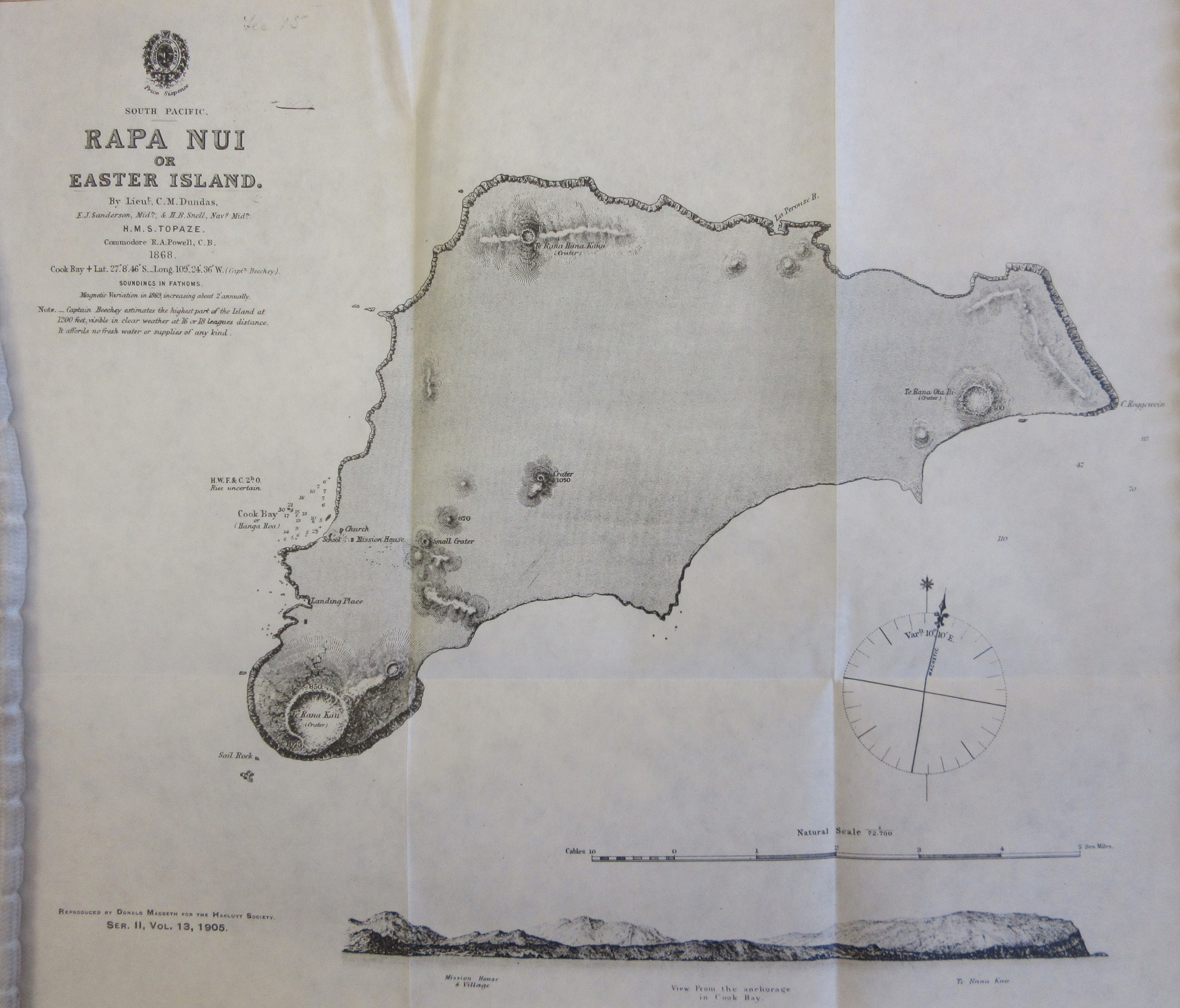

These maps come from a remarkable collection of reproductions of original books on early exploration and travel published by the Hakluyt Society. Formed in 1846 and originally intended to be called the Columbus Society at the first meeting it was decided that Sir Richard Hakluyt (1552-1616), a writer and collector of travellers tales, better reflected the goals of the Society. The first chairman was the famous geologist Sir Roderick Murchison. This image shows Roggeveen measuring one the Maoi, one of the 887 listed either on the island or in museums throughout the World.

These maps come from a remarkable collection of reproductions of original books on early exploration and travel published by the Hakluyt Society. Formed in 1846 and originally intended to be called the Columbus Society at the first meeting it was decided that Sir Richard Hakluyt (1552-1616), a writer and collector of travellers tales, better reflected the goals of the Society. The first chairman was the famous geologist Sir Roderick Murchison. This image shows Roggeveen measuring one the Maoi, one of the 887 listed either on the island or in museums throughout the World.