Over a decade ago, the Bodleian Map Room moved its collections out of what was then the New Bodleian Library, for the building to be completely redeveloped into the shiny new Weston Library. Anything uncatalogued was given a barcode and brief record to locate it in the new storage facility in Swindon. It was while tidying up the last few of these that we stumbled across this beautiful panorama of the Grampian Mountains. Everyone loves a panorama, so here it is, showing a view across the Scottish landscape. The hills grow increasingly faint into the distance. Settlements can be located by the wisps of smoke rising from them, presumably from peat fires.

In the foreground a picturesque rocky outcrop is surrounded by colourful heather; this is captioned beneath “The summit of Benclach, 2359 feet above the sea.”

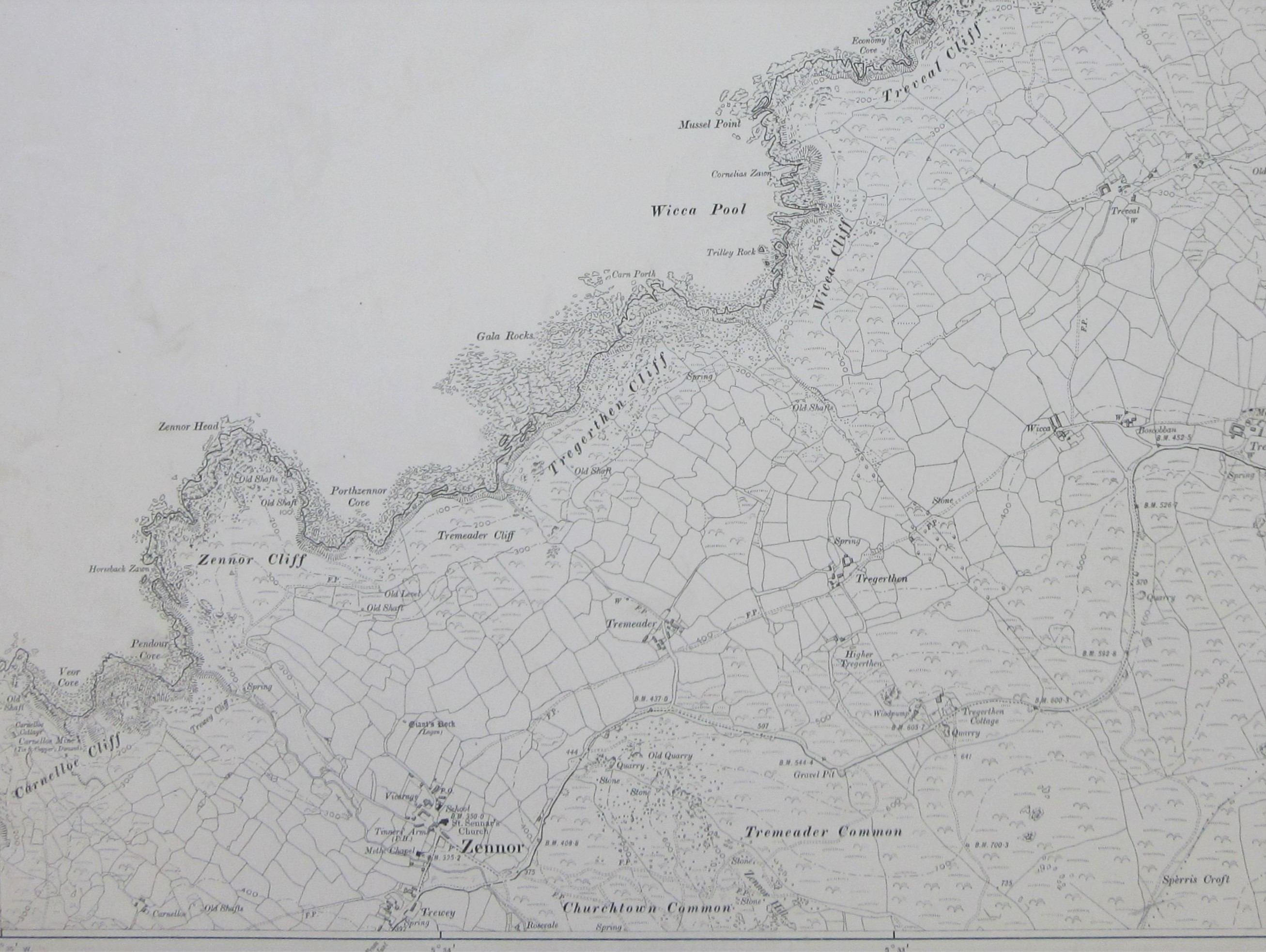

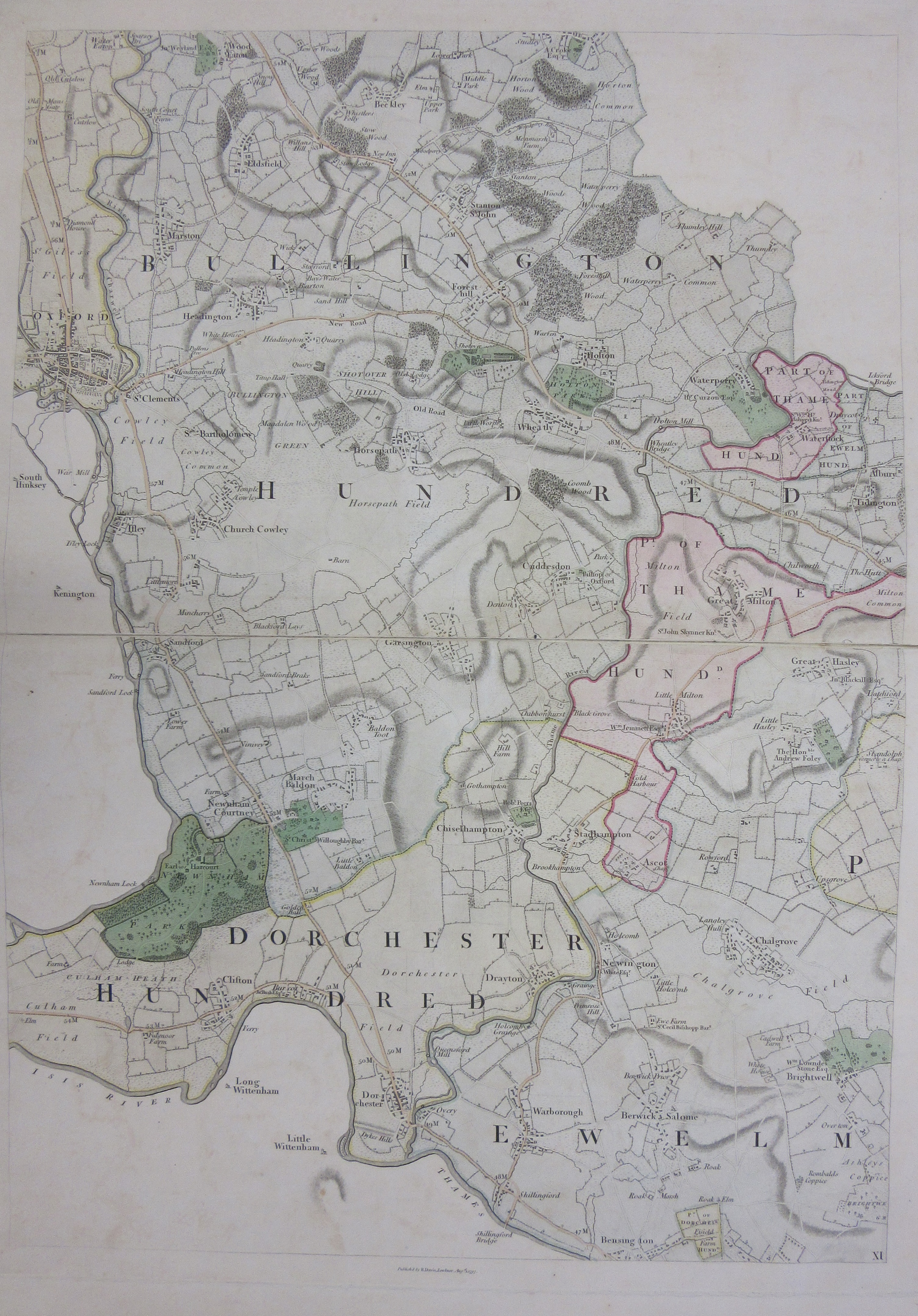

It’s described as “A view of the Grampian Mountains, taken from the Summit of Benclach the highest of the Ochill Hills, a station in the Trigonometrical Survey of Great Britain, situated 28 miles north west from Edinburgh.” There’s a lot of cartographic history packed into that title. The Ordnance Survey has origins going back centuries, but the Roy Map of Scotland from the 1740s and ’50s is often seen as the immediate forerunner to the systematic survey of the whole of Great Britain begun at the very end of the eighteenth century. The survey started at the south coast, mapping the country at 1 inch to a mile, and worked northwards. It took decades to cover England and Wales, and the first published maps OS maps of Scotland were later still. However, the initial Trigonometrical Survey which worked its way up Britain, plotting exact locations by a process of triangulation, had reached southern Scotland by the 1810s. The panorama was both drawn and published by James Gardner, previously “employed on the Trigonometrical Survey”.

From 1823 Gardner was established in London as a publisher and seller of maps, and sole agent for the sale of Ordnance Survey maps; he retired in 1840 and the business passed to his son. The mention of his earlier role as a surveyor probably indicates that the view was made to be accurate rather than simply an artwork, and certainly seems to show a pride in being involved in this great scientific endeavour. There is an outline diagram underneath which names the mountains, settlements and other features, making the panorama informative as well as beautiful.

The point of origin is probably Ben Cleuch in the Ochil Hills. There is a note stating that it covers “about 85 degrees of the horizon” – nearly a quarter of a circle, stretched out to a view almost two metres long. The view was engraved by Daniel Havell in London, and printed in colour, a quite early example of a colour lithograph.

The point of origin is probably Ben Cleuch in the Ochil Hills. There is a note stating that it covers “about 85 degrees of the horizon” – nearly a quarter of a circle, stretched out to a view almost two metres long. The view was engraved by Daniel Havell in London, and printed in colour, a quite early example of a colour lithograph.

A view of the Grampian Mountains, from the Summit of Benclach the highest of the Ochill Hills / delineated and published by J. Gardner … 1820. C18:5 (93)

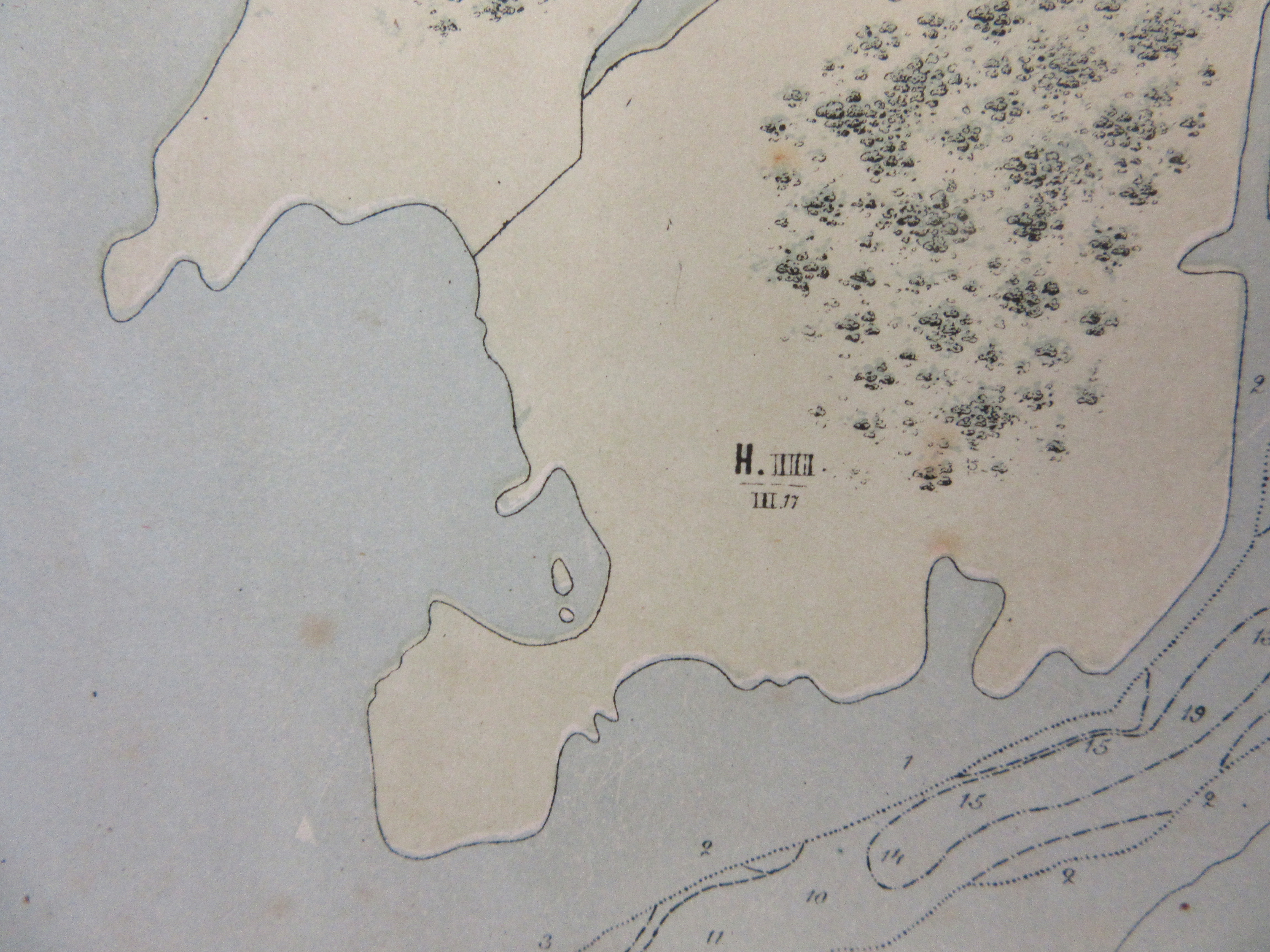

The map was found amongst the papers of Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon. Why is this hand drawn map of part of the coast of Brazil amongst the state papers of an adviser to an English king? The answer is in the accompanying written text described as a “Remonstrance concerning advantages for his sacred Majestie”, directed to Charles II. It explains that the map is a “true copy of an original gotten out of the secret cabinet of the Amsterdam West India Company”, and describes the enormous value of silver that exists to be mined in the area. The text appears to come from Balthazar Gerbier (who also refers to himself by the name Douvilly, a reference to a probably invented noble ancestor). At this time Gerbier, formerly a courtier, diplomat and art consultant, had fallen on hard times since the Restoration. He had previously taken part in an unsuccessful expedition to Guiana in search of gold. His extravagant claims regarding silver around Fortaleza do not appear to have been followed up.

The map was found amongst the papers of Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon. Why is this hand drawn map of part of the coast of Brazil amongst the state papers of an adviser to an English king? The answer is in the accompanying written text described as a “Remonstrance concerning advantages for his sacred Majestie”, directed to Charles II. It explains that the map is a “true copy of an original gotten out of the secret cabinet of the Amsterdam West India Company”, and describes the enormous value of silver that exists to be mined in the area. The text appears to come from Balthazar Gerbier (who also refers to himself by the name Douvilly, a reference to a probably invented noble ancestor). At this time Gerbier, formerly a courtier, diplomat and art consultant, had fallen on hard times since the Restoration. He had previously taken part in an unsuccessful expedition to Guiana in search of gold. His extravagant claims regarding silver around Fortaleza do not appear to have been followed up.