Maps are 2-dimensional representations of a location, created by a cartographer, editor or publisher. Most are straightforward in that they portray accurately (hopefully) that area covered. Occasionally they mislead, either accidentally or deliberately. A misleading map played a part in one of the most famous and important events in World history. Christopher Columbus’s decision to sail west to reach the East Indies was partly due to a map in an atlas of maps by the Classical cartographer Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100-170). While this map was the most up to date

based on contemporary knowledge it missed parts of the Earth as yet undiscovered by European explorers. Without the knowledge of a whole new continent in the west Columbus set sail hoping to find a new and quicker route to the East Indies but instead discovered the New World ( To read more about how the Bodleian’s copy of a Ptolemy atlas has an amazing connection with Columbus click here).

Another intriguing example of misleading cartography is the representation of ‘Phantom Islands’ on maps. These are islands which for a number of reasons; low cloud, recording already surveyed locations as ‘new islands’ and mirages have all been the cause in the past, are mapped and then continue appearing on maps as cartographers use old information, until a new survey is made or a ship reports that the island doesn’t actually exist. The inset on the right is of a map made in 1710 of South America which features Pepys Island, named after the famous diarist who was also the Secretary to the Navy. Lying off the coast of Argentina and first recorded in 1683. Pepys Island was shown on maps for over 150 years until 1839, when was finally proved not to exist. This extract is from South America corrected from the observations comunicated to the Royal Society’s of London & Paris… by John Senex, which featured in a blog here

maps. These are islands which for a number of reasons; low cloud, recording already surveyed locations as ‘new islands’ and mirages have all been the cause in the past, are mapped and then continue appearing on maps as cartographers use old information, until a new survey is made or a ship reports that the island doesn’t actually exist. The inset on the right is of a map made in 1710 of South America which features Pepys Island, named after the famous diarist who was also the Secretary to the Navy. Lying off the coast of Argentina and first recorded in 1683. Pepys Island was shown on maps for over 150 years until 1839, when was finally proved not to exist. This extract is from South America corrected from the observations comunicated to the Royal Society’s of London & Paris… by John Senex, which featured in a blog here

These are just a few examples of how maps can, without meaning to, lie (or, to be fairer, give incorrect information). There are a number of examples though of publishers deliberately making mistakes on their maps. Soviet-era maps intended for Western visitors were often misleading to avoid Western states having accurate mapping of Soviet cities and towns. Some commercial publishers include false information amongst their maps to catch competitors out who have copied work without acknowledging or seeking permission, This is more common on street atlases, which is why the these false inclusions have the rather wonderful name of ‘trap streets’.

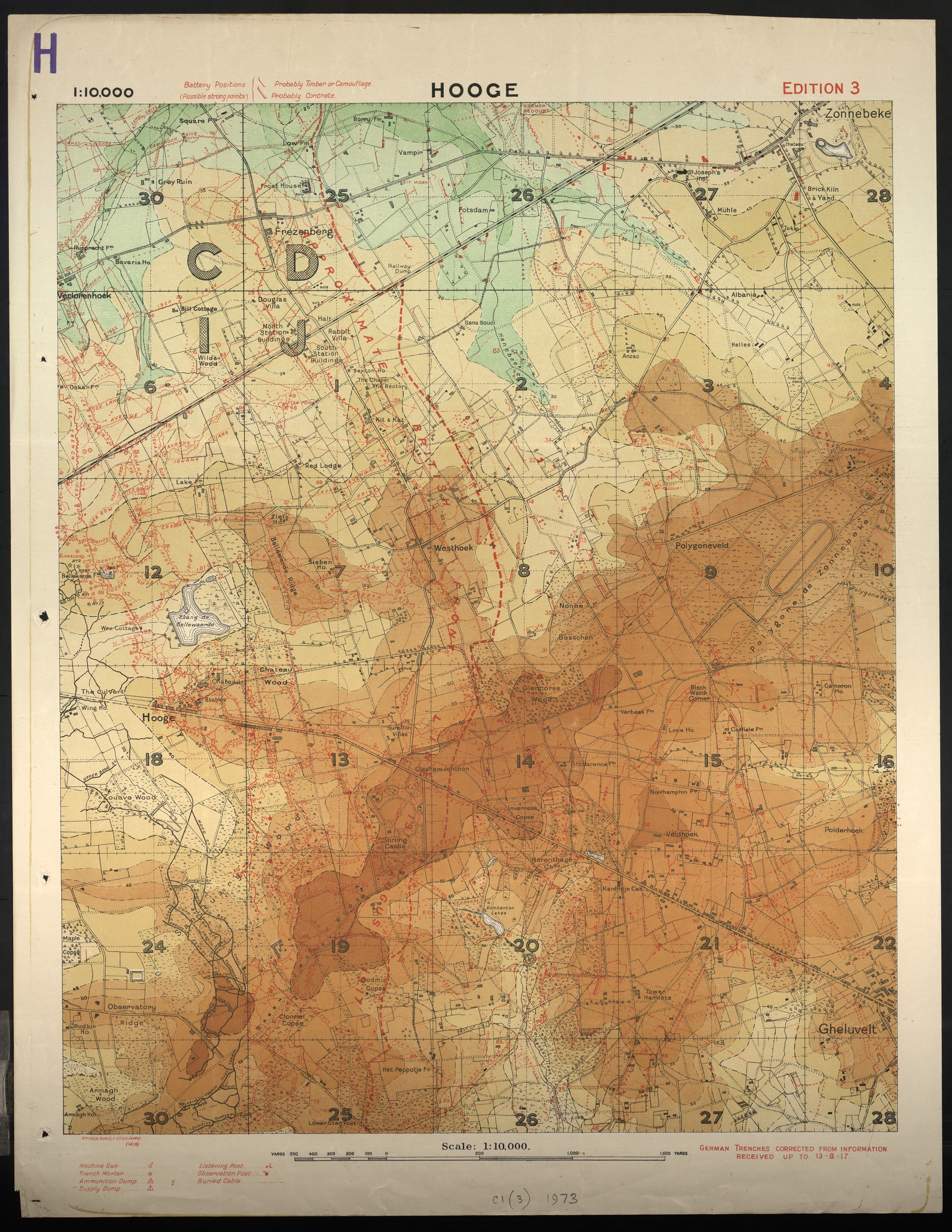

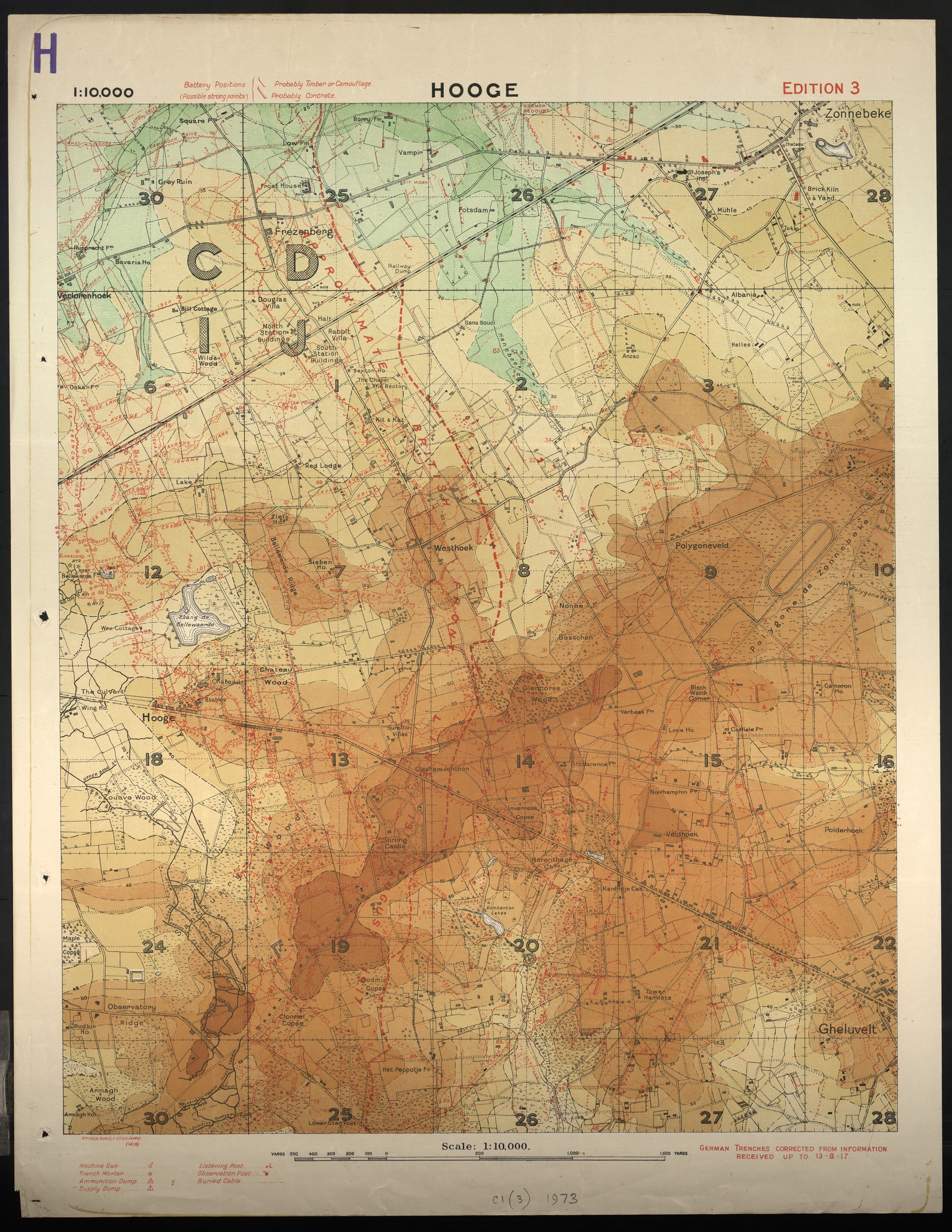

The reason for this long preamble is that, like other colleagues in the Map Room at the Bodleian, i’ve spent a good part of the lockdown going through scanned images in folders and recording shelfmarks and other details (see the blog ‘Rummaging through virtual maps’ directly below). My work has involved working through the Bodleian’s trench and other maps of the First World War. These are amongst the most evocative of all the maps in the collection, full of names that for anyone interested in history are instantly recognizable; Mametz Wood, Passchendaele, the Somme, Messines and Vimy Ridge. These are maps made for, and used in, the planning and carrying out of operations that in some cases cost the lives of thousands while making miniscule gains in land. But the reason for including these maps in this blog is that the more detailed trench maps, at 1:10,000 and 1:20,000 scales, ultimately, but necessarily, lie. For example take this extract of a trench map covering the French city of Lens.

The red lines to the right are the German front-line and support trenches, the blue lines are the Allied trenches (most trench maps only show the Allied front-line, it’s not often that you have so much Allied trenches shown in case the map was captured by the enemy). These trenches, the information relevant for the December 1917 date of the map, are overlaid onto a pre-war map showing what looks like a normal French city with railways, roads, houses and churches. In reality the city had been heavily bombed during the War with most of the buildings levelled, and the trenches were made out of the rubble caused by bomb damage.

A better example of the contradiction between map and ground can be achieved by comparing this map covering Chateau Wood with a photo of the same area. Chateau Wood is east of the Belgian city of Ypres and had been behind the German front-line until Allied advances towards the Passchendaele Ridge in the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917.

Hooge, 3rd ed, 1917. C1 (3) [1973]

On the trench map the Wood has field boundaries and tracks through the trees (Chateau Wood is east of Hooge in square 13, and can be seen in this extract). Compare the calm and ordered landscape portrayed on the map with the reality on the ground from this photograph of duckboard tracks going through the wood taken in October after advanced beyond the wood and beyond towards Passchendaele.

On the trench map the Wood has field boundaries and tracks through the trees (Chateau Wood is east of Hooge in square 13, and can be seen in this extract). Compare the calm and ordered landscape portrayed on the map with the reality on the ground from this photograph of duckboard tracks going through the wood taken in October after advanced beyond the wood and beyond towards Passchendaele.

Ultimately though how do you map land like this which has had all recognizable features long-since destroyed and ground constantly altered by artillery fire? During major battles maps were produced on a regular basis to keep as up to date as possible with an ever-changing front-line, hard enough to do if just mapping the new positions of trenches, impossible to complete if you mapped each new shell crater or destroyed pill-box. To have vital and ever-changing information such as trenches and enemy positions printed over a landscape that was no longer there but was shown on pre-war mapping was, with the need for accurate and quickly produced maps, the only option, but by necessity a lie.

Ultimately though how do you map land like this which has had all recognizable features long-since destroyed and ground constantly altered by artillery fire? During major battles maps were produced on a regular basis to keep as up to date as possible with an ever-changing front-line, hard enough to do if just mapping the new positions of trenches, impossible to complete if you mapped each new shell crater or destroyed pill-box. To have vital and ever-changing information such as trenches and enemy positions printed over a landscape that was no longer there but was shown on pre-war mapping was, with the need for accurate and quickly produced maps, the only option, but by necessity a lie.

For more on trench maps and the Bodleian Library click here

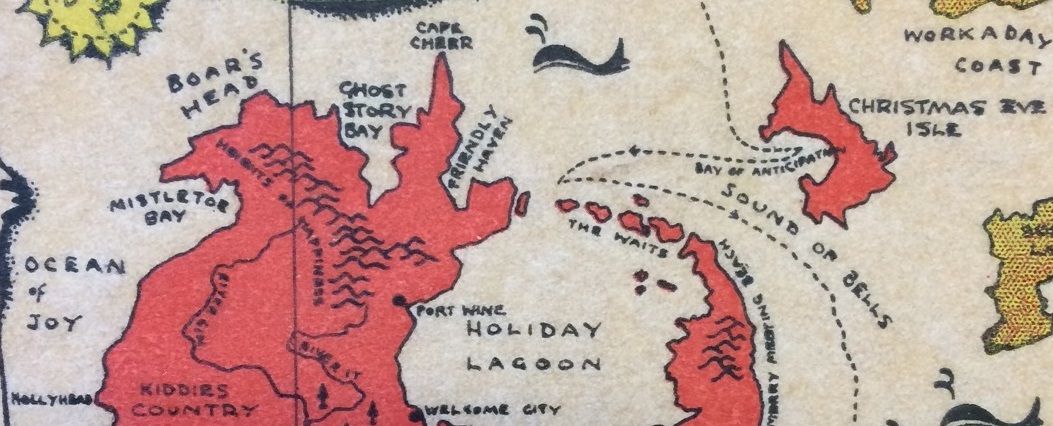

Everyone has heard of Christmas Island, but have you heard of Christmasland? The (fictional) island appears on this cartographic Christmas card from the 1930s. Christmasland: Captain Jolliman’s voyage of discovery in ye “Friendship” (see what they did there?) shows a route from Humdrum Drearyland, with its Workaday Coast, to Christmasland.

Everyone has heard of Christmas Island, but have you heard of Christmasland? The (fictional) island appears on this cartographic Christmas card from the 1930s. Christmasland: Captain Jolliman’s voyage of discovery in ye “Friendship” (see what they did there?) shows a route from Humdrum Drearyland, with its Workaday Coast, to Christmasland.