Guest blog entry by Peter Bergamin

Chaim Arlosoroff (1899-1933) was of one of the most important and brilliant figures in Zionist political life in British Mandatory Palestine. His killing remained the Jewish political murder until the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, in 1995.

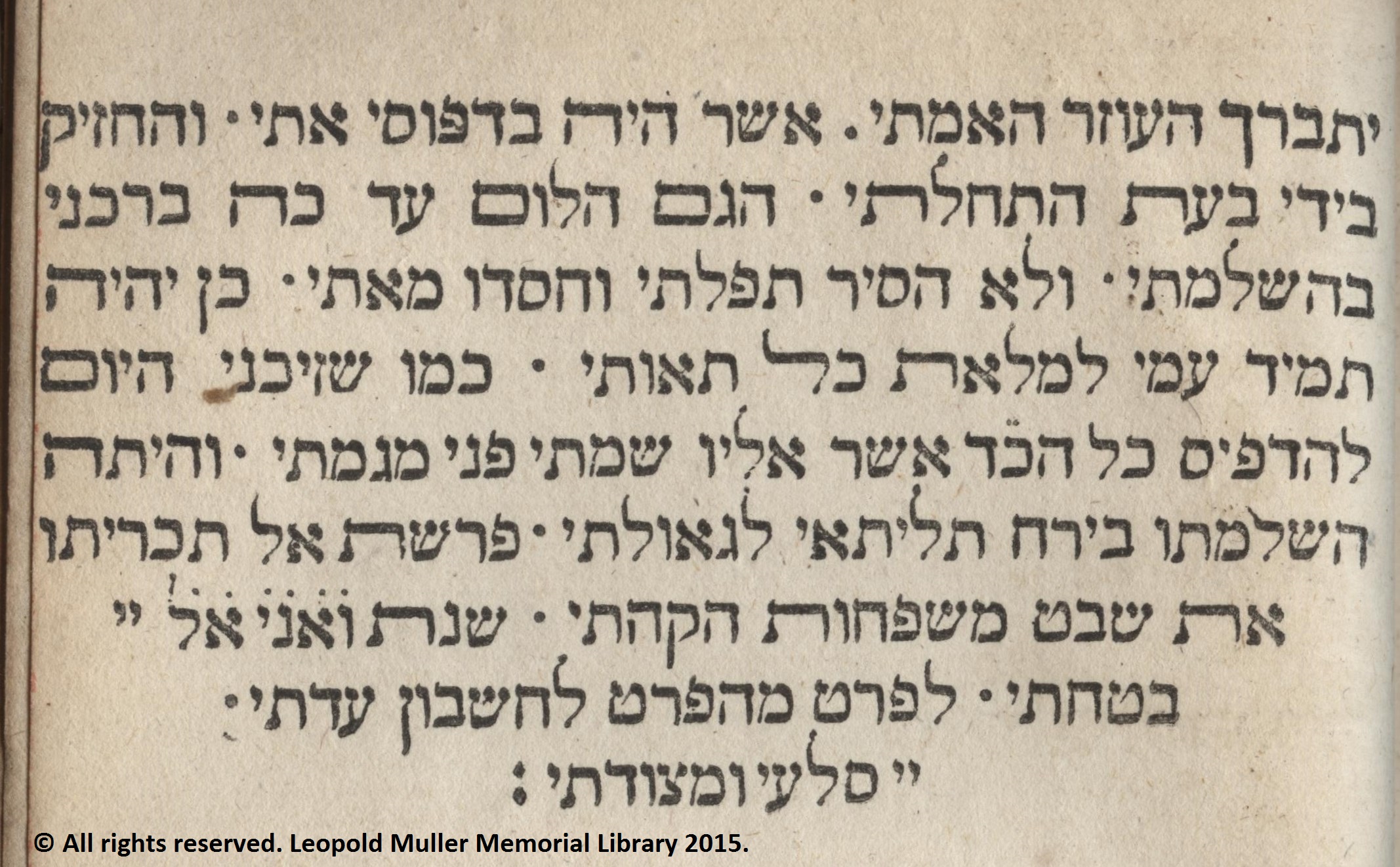

Arlosoroff’s Ex Libris from our collections

Born Chaim Vitaly Viktor Arlosoroff on 23 February 1899 in Romny, Ukraine, Arlosoroff’s position reflected that of many other Jews of his location, and time. The grandson of a rabbi, and son of a wheat and lumber merchant, he grew up in a comfortable semi-assimilated familial environment that straddled Russian, German, and Hebrew cultural influences. In 1905, in the wake of anti-Jewish pogroms, the family fled to East Prussia, eventually settling in Königsberg. And in 1914 – having successfully avoided deportation back to Russia, due to the outbreak of war – the family moved once again, to Berlin. Arlosoroff identified more and more with German national culture, although his Russian citizenship precluded him from joining the German war effort.

It was during this time that he began to embrace socialist ideals, due in no small part to the identity crisis he experienced as a ‘Russian’ who – due to his existential circumstances – now identified with his German national-cultural surroundings, and finally, as a Jew in all of this, a factor that fundamentally set him apart from both of these national cultures. Thus, his socialism looked increasingly to Jewish sources, and he was especially influenced by Martin Buber, A. D. Gordon, and Gustav Landauer. By 1919, Arlosoroff had joined the Zionist party HaPoel HaTzair (‘The Young Worker’), which had been founded – inter alios – by A.D. Gordon, and subscribed to his ideology of the ‘redemption of the land of Israel’ through agricultural endeavours. That same year, he published what became his best-known work, Jewish People’s Socialism, which sought to combine universal socialist ideals with a strong sense of ethnic-national – indeed, ‘völiksch’ – Jewish identity. This contributed to his rapid rise within the party. In 1924, he emigrated to British Mandatory Palestine, where he quickly established himself as a leader in the Zionist Labour movement, and helped effect a merger between HaPoel HaTzair with the more Marxist Poale Zion, into the Mapai Labour Party. Mapai would enjoy political hegemony over the land for years to come, and Arlosoroff represented the party in the Zionist Executive, and as Head of the Political Department of the Jewish Agency for Palestine.

It was in this latter role that Arlosoroff negotiated the HaAvara Agreement with the Nazi Party, in 1933. It permitted the transfer of Jewish capital from Germany to Palestine by immigrants or investors in the form of German goods. Although it protected – to some degree – the capital of German-Jewish emigres to Palestine, the agreement also assisted the Germans through increased production and export of goods which, technically, were bought by Jews at the other end. The agreement was highly controversial, and drew harsh criticism from the right-wing Jewish press in Palestine. Two days after he returned from its negotiations in Germany, Arlosoroff was shot and killed while walking on the beach with his wife. The murder has not been solved to this day, but various theories abound. Many believe that Arlosoroff was killed by members of the extreme, ‘Maximalist’ wing of Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Party, and three of the party’s members – Abba Ahimeir, Zvi Rosenblatt, and Avraham Stavsky – were arrested in connection to the murder. All three were subsequently acquitted; Ahimeir, before the trial began, Rosenblatt and Stavsky, after standing trial (although Stavsky was originally found guilty and acquitted only on appeal). Others believe that Arlosoroff was murdered by two Arab youths, in a foiled robbery attempt. And some believe that he was murdered by Nazi agents: not only had he just negotiated the HaAvara Agreement, but he had been on very friendly terms, perhaps even romantically-so, with Magda Behrend – later, Magda Goebbels – just after the end of the First World War. The irreparable damage that such information would have caused to the Nazi propaganda machine, if leaked to the German public, goes without saying.

No matter who killed Arlosoroff, his murder cut short the life and career of one of the most important and brilliant figures in Zionist political life in British Mandatory Palestine. Indeed, Arlosoroff’s killing remained the Jewish political murder until the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, in 1995.