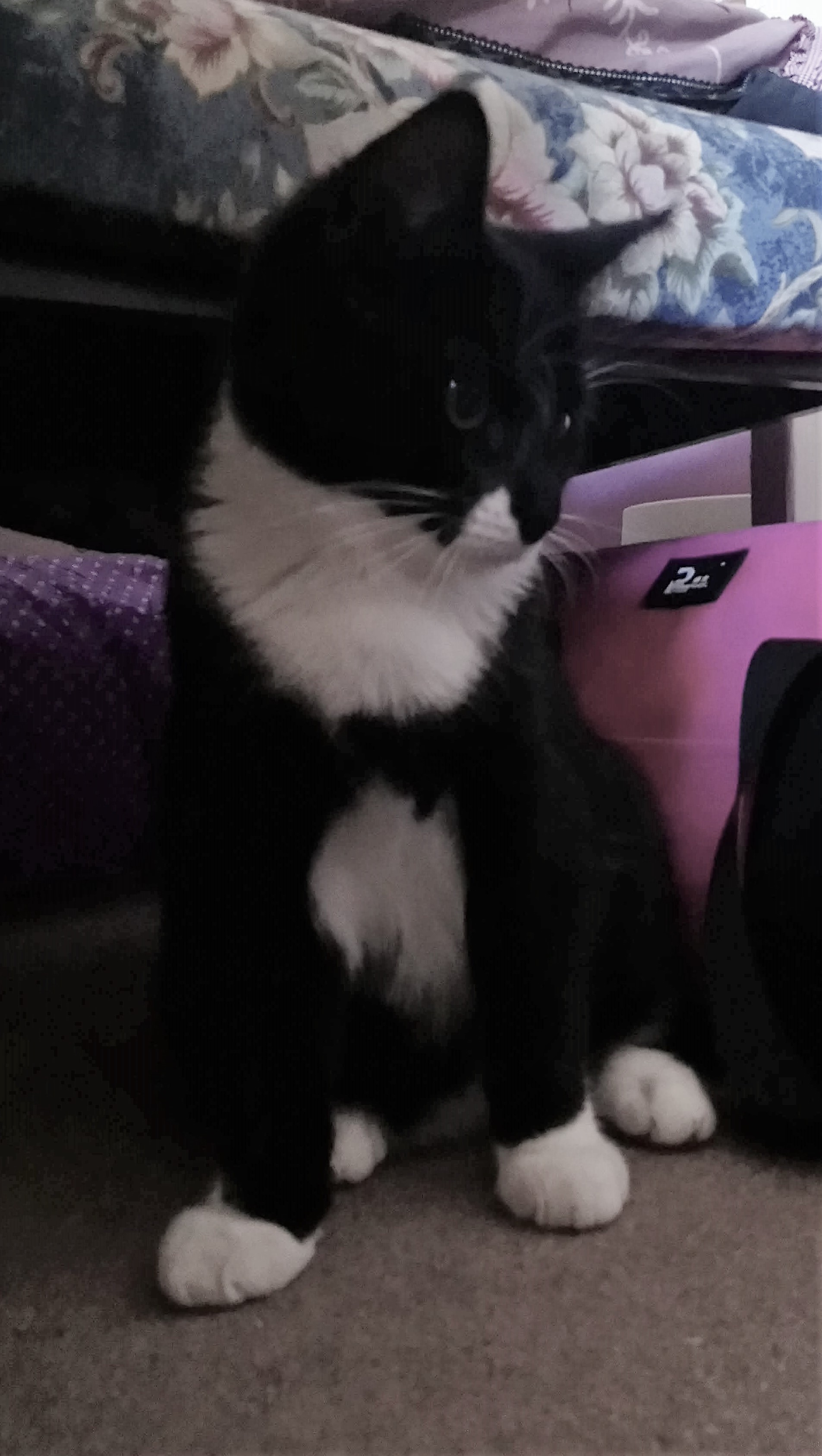

In a previous post I promised to introduce some new members of the Lady Margaret Hall team: Benny (the college cat) and Beyonce, Michelle and Kelly (the college rabbits) have been doing a wonderful job in their roles supporting welfare in the college. Recently though, there hasn’t been as much grass poking through for them to snack on, as LMH has been covered in snow. This is giving the college a cosy, festive feeling even though we are already halfway through term, so in this post I thought I would give an insight into what went on in the library over the winter vacation. (And of course, there will be some photos of Benny and the LMH bunnies.)

While the library might be fairly empty of students over the vacations, there are still plenty of tasks to complete. There are heaps of books hurriedly returned before the end of term, and headphones, socks, and even a pomegranate that have been left behind. But it’s also a chance to catch up on projects that we have less time for during term. Over the recent holidays, this meant an opportunity to start planning and researching the graduate trainee project (which I’m hoping to base around library accessibility issues) as well as an upcoming exhibition showcasing some of our rare books. It also gave me time to make a start on the process of reclassifying a section of the library.

As I have mentioned before, I’m interested in medical knowledge and information, so my supervisor and I decided that it would make sense for me to re-evaluate the healthcare section of the library. As Amy explained in her post, the main part of this process involves analysing books in this section and assigning them a new shelfmark, based on a more current classification framework than they were previously organised by. So what is classification?

![Cartoon elf posing in a card catalogue. Subtitles read: 'I love a good subject-based classification system. [chuckles]'](http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/oxfordtrainees/wp-content/uploads/sites/133/2019/02/alfur.jpg)

There are various systems of classification, and different Oxford libraries use different systems. Some have their own unique system; several others use Library of Congress. Each system has advantages and disadvantages in its usability. Each also derives from its own specific time and place, and therefore reflects cultural ideas about the value of and relationship between areas of knowledge.

For example, the Library of Congress system, widely used in North American academic libraries, arranges materials in a way that does not reflect Native American and First Nations worldviews or allow for the diversity of these cultures. It also places Native cultures in the ‘History’ section despite these cultures still being present today. Librarians designed Indigenous classification systems in response. Several of these have been adopted in Indigenous collections, such as Brian Deer Classification which was developed by Kanien’kéhaka Mohawk librarian Brian Deer in Canada in the 1970s.

At LMH we use Dewey Decimal Classification, developed by American librarian Melvil Dewey between 1873 and 1876 – but like many libraries we adapt it to our particular needs, and our law collection operates a separate system. As the name suggests, the style of Dewey Decimal uses numbers. Each main class of knowledge is given a ‘hundred’ number, such as the 600s for ‘Technology’ in the 23rd edition of the DDC schedules. Within that, the ‘tens’ are divisions under this umbrella: 630 for ‘Agriculture’, for example. Each of these is broken down further into sections, giving us 636 for ‘Animal husbandry’. At this point, if we wanted to be more specific, we could start to add decimal places. 636.8 is (domestic) ‘Cats’; 636.82 is ‘Shorthair cats’, like Benny.

However, books that take different approaches to the theme will be in different places: our book on cats in mythology is in number 398, while if Benny wrote an autobiography it might be placed in 920. There are often multiple possible classifications for a book: How broad or close does it need to be? Where should it go if it spans several disciplines? Where would our readers expect to find it? Which of our existing books should it be classed with? And then there are tables allowing further expansion of the number, based on facets like location and time period.

To complete the shelfmark, we add the first three letters of the author’s last name, and other fields if necessary. If we had two copies of Benny D Cat’s autobiography, they might be labelled 920 CAT (A) and 920 CAT (B). This new style of shelfmark is another reason why we are reclassifying our collections; previously we arranged items by acquisition number. By arranging by author and year we hope to group and order our materials in a way that helps our readers navigate them. It’s also an opportunity to cover faded shelfmarks with more legible labels, and to weed out old editions of textbooks that are no longer being borrowed.

Some of the reclassified books are moving to completely different locations, causing a bit of an upheaval in the medical sciences room. But by the time the bunnies are hopping around in the sun again, our skeleton Freddie might be looking less confused about where all the books have gone.

Recent Comments