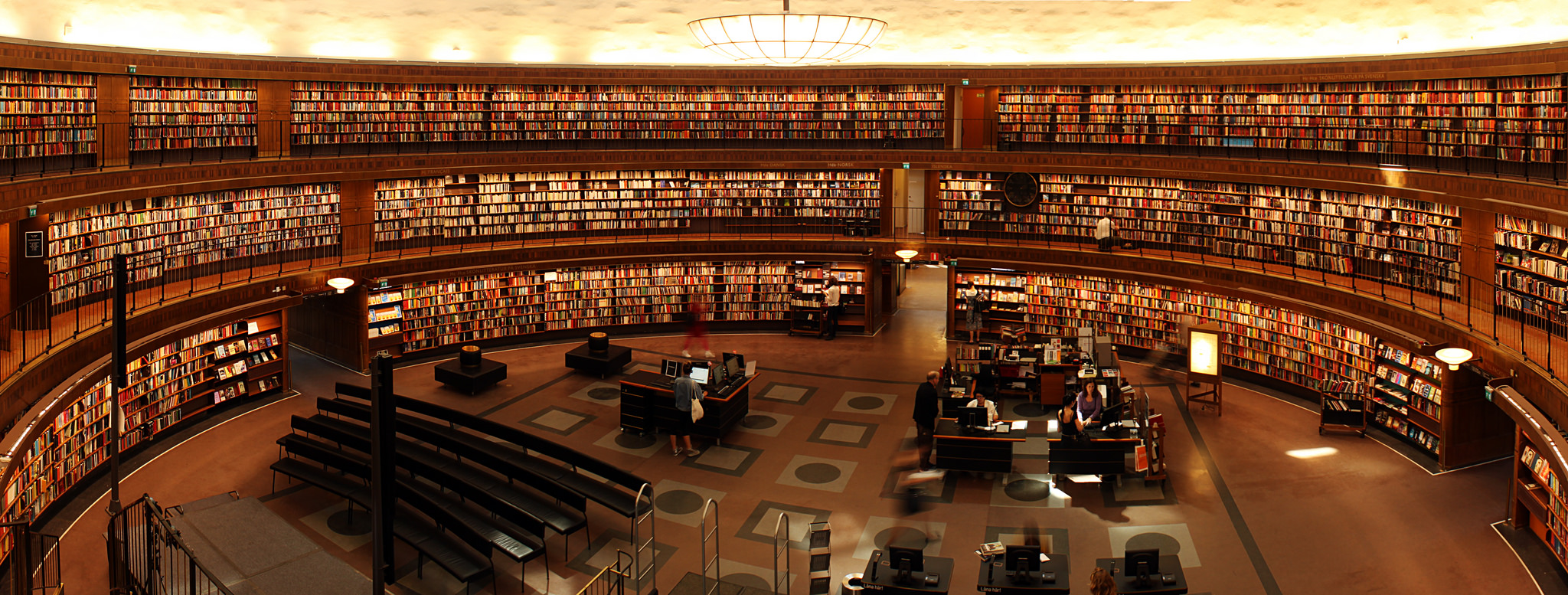

In exciting (albeit belated) news, Saturday 7th February was National Libraries Day! In this age of austerity and self-service, where both public and private institutions are stretched, and arguably at risk of undervaluing the social importance of access to and curation of

culture, an annual celebration of libraries: libraries academic, libraries special and libraries public, and of course of the staff and volunteers who keep them running, using their

enthusiasm, specialist knowledge and research skills to bring readers and books together. It was a day for exhibitions, author visits, talks, special events and shelfies; to find out more, check out where you’ll find juicy library-related news items, including a speech by

John Lydon (yes, that one).

To mark the occasion, here’s my account of one of the reasons the Bodleian Libraries are key members of the global research community: legal deposit.

The Bodleian Libraries form one of six Legal Deposit (LD) Libraries in the UK; the others

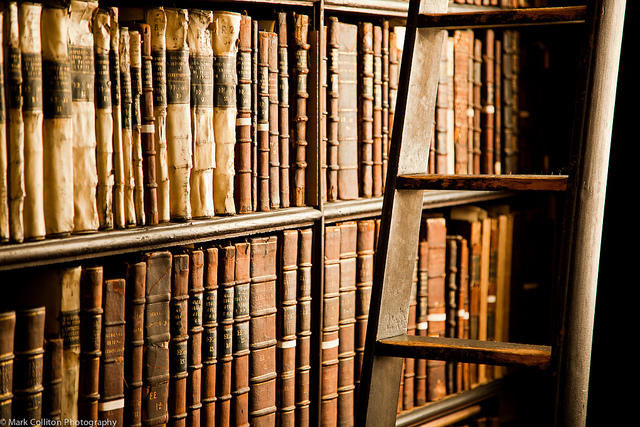

being Cambridge University Library, the British Library, the National Libraries of Wales and of Scotland, and Trinity College Dublin. Each of these libraries is entitled to receive a print or digital copy of every item published in the UK. Every published item received is to be

preserved as far into the future as possible, so that a centuries-long cultural record of the

nation will always be available to scholars, authors, publishers and others who need it.

A Clever Deal

Legal deposit began in 1610 as an agreement between Thomas Bodley and the Stationers’ Company; his new library in Oxford would be stocked with everything published under royal license, and in return the Bodleian would keep these works for the benefit of future generations. In 1662, the Royal Library and Cambridge University Library gained the same privilege, forming the basis of what would later become the Copyright Act; this was

continually built upon in law to become the system of legal deposit as we currently know it.

My Place in Perpertuity

The BLL receives those LD books related to law, so one of my weekly jobs is to process these items. When the books start coming in on Thursday, on my copy of the VBD (see my previous post) I record which books I’ve received, which are missing and any conflicts.

These occur when more than one library has an interest in a particular title; a book on the Civil Rights Movement and law, for example, might be selected by the Vere Harmsworth

Library as well as us. The conflict list is emailed round to the librarians who selected the books in question, who decide where they will go based on reading lists, the perceived needs of readers and so on. I count them for our stats, then tattle and edge-stamp them.

Some of the books arrive with blue flags; these have minimal-level catalogue records and need updating. In the Aleph cataloguing module, I bring up the MARC21 record and search for similar ones, from the British National Bibliography, the Library of Congress, WorldCat, or Copac, and I pick the one that best conforms to RDA standards. Next, I save the

downloaded record as “Provisional”; it’s lovely when no error messages come up, which means I chose a good, sound record. Lastly, I hand all the books over to the cataloguing team, who use the record I downloaded as a base to work from.

Books to cross my desk recently have covered topics as diverse as oil and gas law,

cybersecurity, hate crime, the use of torture in counter-terrorism, the regulation of

tobacco; last week’s list even included a monograph we didn’t eventually get about the

legal status of whales vs. elephants.

Legal Deposit and the Bodleian

It’s estimated that overall, the Bodleian libraries receive 80,000 physical LD monographs per year, and 78,000 serials. All these resources have to go somewhere, and the creation of shelf space is an ongoing concern; Sarah and Hannah’s November blog post on the BSF gives an idea of the problem’s scale.

Overall, however, our LD entitlement benefits the Bodleian libraries immensely, in

allowing us to provide access to a much wider range of scholarly works than if we relied upon purchases and donations alone. Oxford’s libraries provide a uniquely thorough

resource for research, and it is satisfying as a librarian to take my small part in preserving the UK’s intellectual and cultural heritage in perpetuity. Were he alive today, Bodley would surely be awed at the quantity of legal deposit material being added daily to Oxford’s

collections; and it all started with his one canny idea.

Really good post! All the best from the British Library newspaper reference team!

Thanks! Have a good weekend all of you